(These are notes of a course given at Birkbeck College by Carol Jacobi in 2005/2006)

19thC The Nude

The Nude

See the books – Bodies of Modernity, Gaab. Thames & Hudson, (stripy yellow series) very good. “Pictures of Innocence” on childhood.

Alison Smith The Victorian Nude

Edited catalogue for the Tate exhibiton on the Victorian Nude., published by Tate, has some useful articles.

(No slide list until next week)

The Classical Nude

Slide 1: Polykleitos, Doryphrous (Spear Bearer) C5th BC, Roman copy

Sometimes called “The Canon” after the book he wrote and which he described the perfect proportions of an ideal figure.

Nudity stood for divinity in Ancient Greece, that is above or out of this world. It represented the acme or supreme state. Stewart in “Art, Desire and the Body” analyses Greek nudes much more deeply. They have a calm, poised wholeness as a response the the counterpoint of the pain and death of battle.

“The chief forms of beauty are order, symmetry, definiteness,” Aristotle.

The construction of the Greek nude looks natural but is very artificial. The body has many artificial constructs – for example, the body was seven head heights, it has an “iliac crest” and a line halfway down their arm on the inside of the elbow joint. The iliac crest provides two-fold symmetry, left/right and a line halfway up the body. Legs are actually shorter. It represents perfect order and control and a realisation of the Ideal and perfection.

Females are clothed for modesty, virginity at this time. Parthenos means virginity and the Parthenon is part of a ritual giving of a tunic (peplos) to Athena.

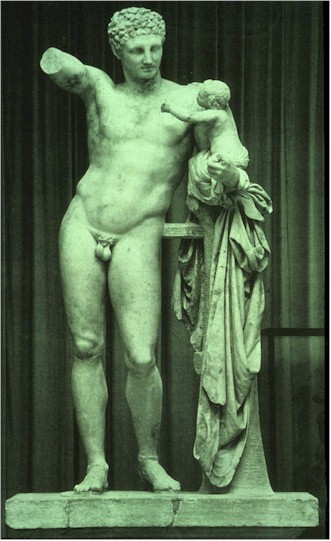

Slide 2: Later Greek nudes, Praxiteles, Hermes and Dionysus, C4th

Hermes and the “baby” god Dionysus (from Praxiteles around 343-330 BC his only original work survived, there are some who say that it was produced by some of the Praxiteles school) found the 8th May 1877 at the Hera temple now at the museum of Ancient Olympia. His missing legs below the knee were restored in plaster, also part of his right hand are missing. Hermes and Dionysus are brothers as their father is Zeus. Art Specialists tell us that the face contains an asymmetry. If one looks the face from the left, is sorrowful, from the right it is smiling and seen from the front it is calm. Therefore if we move and look Hermes face it seems not to be static. Made from Parian marble. Praxiteles (390- c.330 BC) lived in Athens about 360 BC, his work is mainly known from Roman copies. Why does the baby Dionysos stretches his hand? Probably because Hermes held a brunch of grapes that Dionysos likes so much.

This C4th sculpture is much “softer” than the C5th Polykleitos. It is not as shiny and has a more sinuous body. It is associated with a story of the baby and grapes, it has a narrative, there is more action. Iti s almost flirtatious, what today we call feminine. We are being invited to enjoy it not just worship the god.

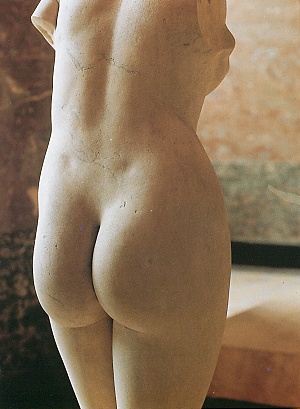

Slide 3: Praxiteles, Aphrodite of Cnidos

Slide 4: Praxiteles, Aphrodite of Cnidos, rear view

A cult image of Aphrodite. The story goes that Praxiteles made two sculptures, one clothed and one naked and the people who commissioned it chose the clothed. The people of Cnidos then chose the naked and built a circular temple to house. It became one of the first tourist attractions. The pretext for her nudity is bathing, she covers herself (the pose is called puder) but with an ambigious gesture that may be a covering or an uncovering. She represent sdivinity in all its glory, a once in a ifetime event. Note the gradual tranistion of the marble representing the skin. It would have been polychromed but this was only discovered recently.

Copied from

“The Aphrodite of Cnidus was part of a collection of classical statues assembled by Lausus, grand chamberlain at the court of Theodosius II (AD 402-450). Two Bzyantine chronicles refer to its loss, both ultimately derived from a sixth-century history by Malchus of Philadelphia, who had described the fire of AD 475. The Suda, a tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia, indicates that he wrote a history narrating “the burning of the public library and of the statues of the Augusteum a public square, lamenting them with great solemnity and in the manner of a tragedy.”

Cedrenus wrote at the end of the eleventh century and relates that, among the statues in the palace of Lausus, there was “the Cnidian Aphrodite of white stone, naked, shielding with her hand only her pudenda, a work of Praxiteles of Cnidus. Also…the ivory Zeus by Pheidias, whom Pericles dedicated at the temple of the Olympians.” Later, he speaks of the “conflagration in the City which destroyed its most flourishing part… it also destroyed the porticoes on either side of the street Mes' and the excellent offerings of Lausus: for many ancient statues were set up there, namely the famous one of the Aphrodite of Cnidus…”

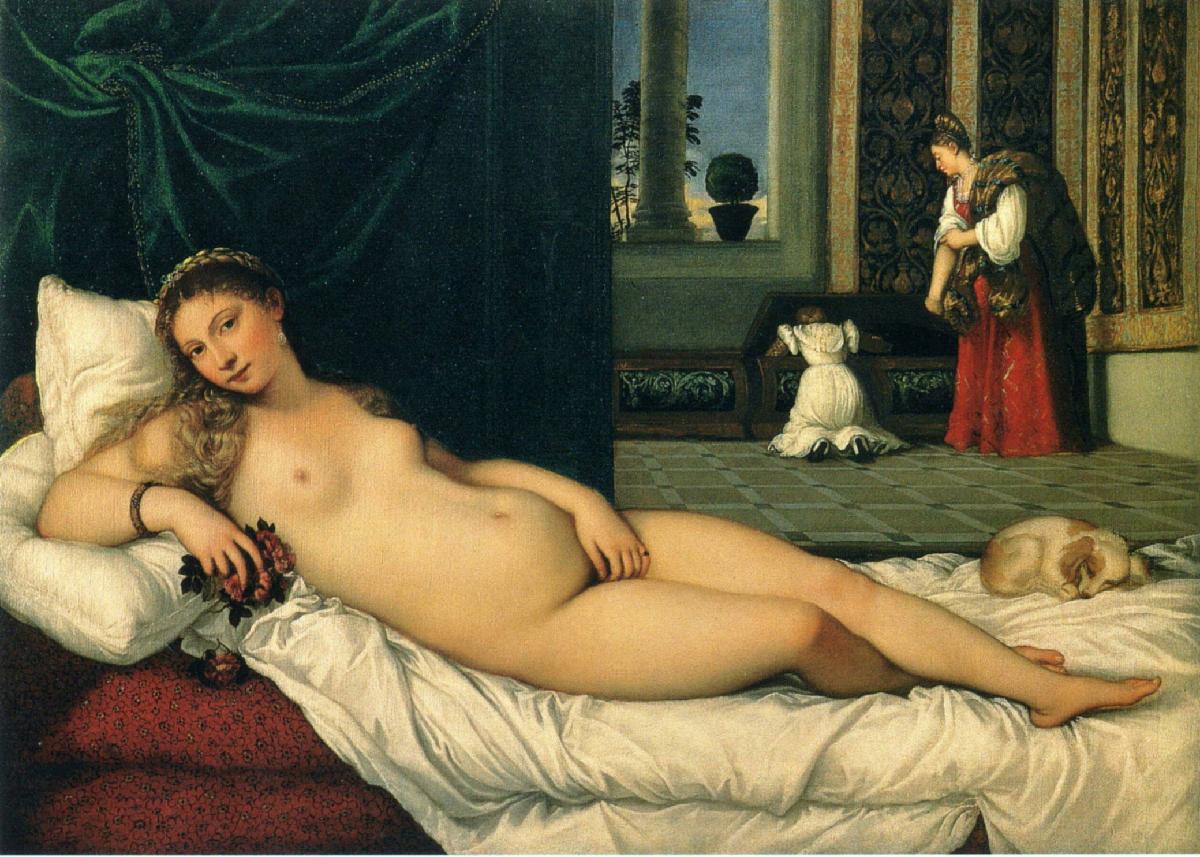

Slide 5: Titian Venus d’Urbino, C16th

A much theorised painting, including Linda Nead (see her first chapter). It is about constructing the spectator. The viewer is assumed to be male; the look is flirtatious, voyeurism, clear perspectival construction giving a sense of being the visual owner. Everything is about access, sees and possesses everything.

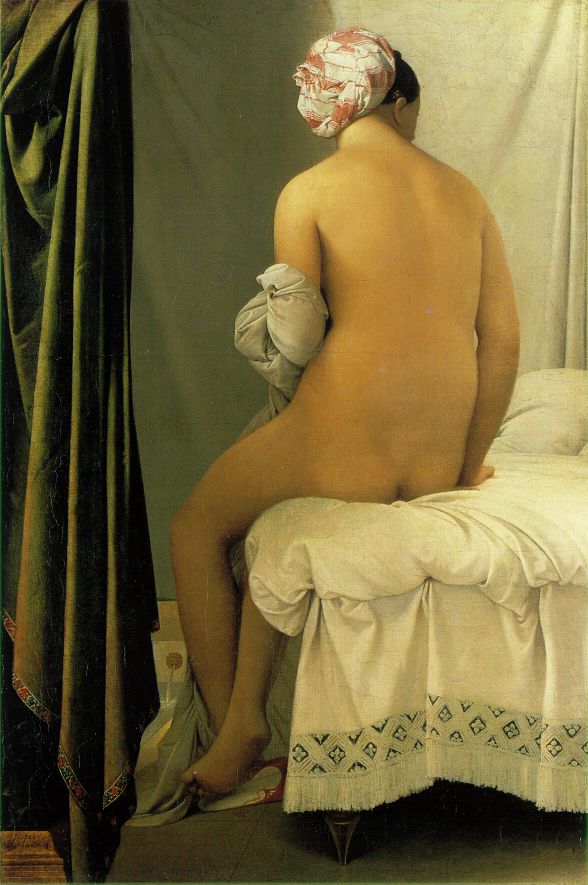

Slide 6: Ingres, Valpicon Bather, 1808

Slide 7: Rubens, Helen Fourment, C17th

His second wife. This is something much more specific, a real person with cellulite rather than an idealised nude.

Slide 8: Boucher

Francois Boucher (1703-1770)

Boucher (1703-1770), was a French court painter and decorative artist of the Rococo period who was influenced by Watteau and Tiepolo. Boucher’s graceful and delicate style were well suited for his role as chief painter for the court of Louis XV.

“An excuse for something decorative.”

Slide 9: Antonio Canova, Venus

More modest, clutching her drapery around her.

Slide 10: Antonio Canova, Pauline Borghese as Venus, 1808

Copied from http://europeanhistory.about.com/library/readyref/blpersonpaulineborghese.htm

“Pauline Bonaparte was the favourite sibling of her elder brother Napoleon, the twice emperor of France. Unlike many of her family, Pauline developed a reputation independently of her brother, creating a life-story which reads more like a salacious novel than a history.

Born in 1780 to Marie-Letizia and Carlo Buonaparte, Pauline spent her early years in Ajaccio on Corsica where she received little in the way of formal education. At the age of thirteen she was involved in the Buonaparte’s nighttime escape from their home, travelling with her mother and siblings to the French mainland, an episode which conveniently – but wholly arbitrarily – marks the start of her effect on the world.

Pauline was a famous beauty before even her sixteenth birthday, attracting a legion of admirers and causing her mother and brothers concern. The young Paoletta initially wanted to marry Stanislas Fr'ron, but her family disagreed; he may have been in Napoleon’s employ, but he was also a forty year old syphilitic with a legendary reputation for philandering. Another admirer, Colonel Victor Emmanuel Leclerc, became Pauline’s first husband on June 14th 1797 at Napoleon’s insistence: he had found them making love in a corner of Milan’s Mombello Palace a few weeks before. Nevertheless, marriage proved little impediment to the young Pauline, whose string of lovers and unrestrained promiscuity only added to the allure of her famed looks. Many women throughout history have been slandered by their enemies in such a way, but Pauline Bonaparte was one of the few whose reputation for nymphomania was deserved.

Leclerc was given command of an army in Haiti and Pauline sailed to join him in 1801, but he perished in 1802 and Pauline returned to France on New Years Day 1803. Historians have often puzzled over why Napoleon then declared a ten day period of mourning for Leclerc, a man he wasn’t remotely close to. His sister was far less concerned, marrying her second husband within eight months, during the August of 1803. He was Prince Camillo Borghese, one of – if not the – richest man in Italy. Pauline’s fidelity remained as absent as ever, once even prompting the Prince to place her under house arrest; it didn’t work. Pauline also scandalised some sections of society when she commissioned two sculptures of herself from Florentine artist Canova: she’d posed almost wholly nude.

Pauline wasn’t simply famous for her physical appetites, but also for her broader love of sensual and material pursuits: she brought masses of clothes, attended party after party and prompted vast amounts of gossip from France’s upper classes. She acted in an impulsive and often childlike way, and it’s not unfair to say she often seemed to inhabit a dreamlike world of her own. In contrast to her mother, Pauline exhibited little in the way of maternal instinct: when her only child by Leclerc – Dermide, born in 1798 – died aged 8, she was nowhere near his deathbed. The incident is notable because Napoleon worked to obscure the events, instead presenting Pauline in a more flattering, or at least imperial, light. Indeed, Napoleon produced plenty of propaganda aimed at defending her.

However, Pauline wasn’t a political climber or a power-hungry schemer like others who surrounded Napoleon and, although she still received considerable gifts from him, the Emperor treated Pauline less lavishly than other siblings. Quite how much this has to do with her treatment of the Duchy of Guantalla, which Napoleon gifted to Pauline and she promptly sold to Parma for six million francs, is unclear; what’s certain, is that this latter Bonaparte wasn’t interested in ruling.

Hitherto unseen aspects of Pauline’s character emerged after Napoleon’s first abdication. She quickly and efficiently transformed her assets – which included a fabulous range of jewelry – into cash before travelling to stay with Napoleon on Elba; she was the only one of his siblings to even visit him. There, she spent money on improving her brother’s lot, ran his ‘court’ and urged him to make a return to power. Such behaviour was in marked contrast to Napoleon’s brothers whose actions are often deemed as treachery and betrayal.

After the 100 Days Pauline traveled to stay with her mother in Italy, before attempting to move into the Palazzo Borghese, family home of her husband; he promptly ended the marriage, and Pauline moved to a property she purchased with her personal wealth near Rome. By now she was suffering from a series of illnesses and, although she remained concerned about Napoleon, she was unable to visit him. True to character, she maintained a lifestyle of parties and lovers, but declined in health, dying of cancer in 1825, aged only 44. The details of her death make an interesting summary of her person: she died in her best dress, asked to be buried in the Borghese family chapel amongst popes – she had been reconciled with her husband towards the end – but also left bequests to every single member of her large family. ”

The Academic Nude

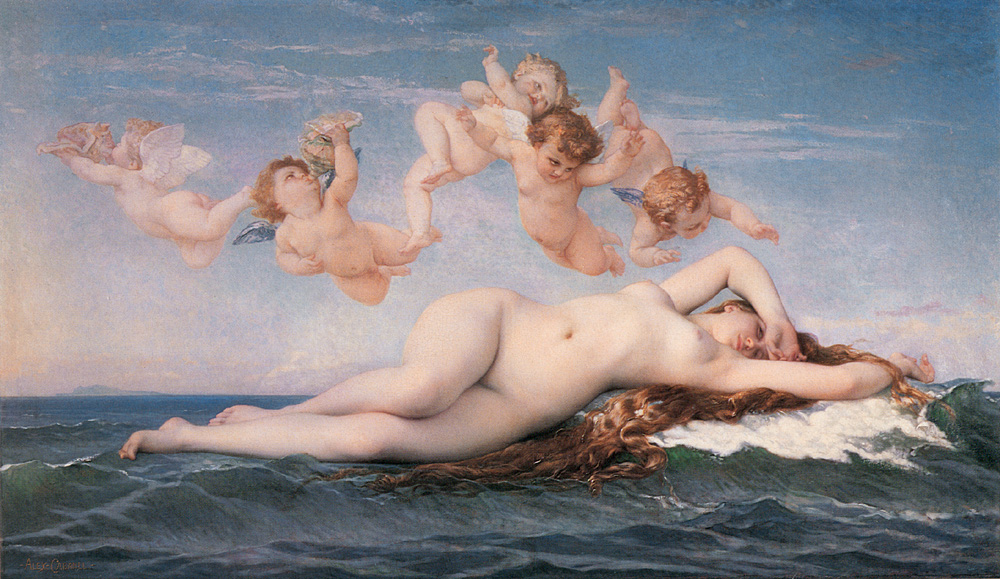

Slide 11: Cabanel, Venus of the Waves, 1863, Musee d’Orsay

Made – cabanes terms of the waves 1863 Muse d’ Unsay.

Slide 12: Poynter, Andromeda, 1865

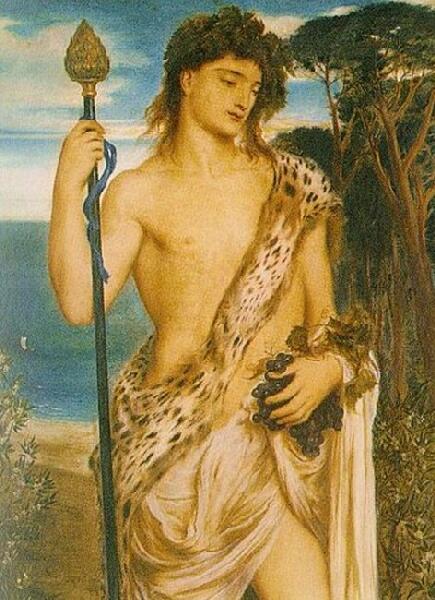

Slide 13: Simeon Solomon, Bacchus

This useful biographical sketch comes from .

Simeon Solomon, an orthodox Jew, was an admirer of Rossetti’s late aesthetic period. He entered the Royal Academy School in 1855 and exhibited his first picture there in 1860. He was quickly befriended by Rossetti, Burne-Jones and the poet, Algernon Swinburne, along with other members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle. During the 1860s he produced a number of fine drawings, gouaches and oil paintings, mainly of religious subjects, especially depicting Jewish ritual, but also classical and allegorical subjects which combine Pre-Raphaelite and aesthetic ideas in a highly individual way. Although Solomon’s pictures owe much to Rossetti and Burne-Jones, especially his allegorical female figures, they have a strong individuality which makes them instantly recognizable.

Solomon’s career disintegrated when, in February 1873, he was arrested for homosexual offences, after which he was completely shunned by all his former friends, including Swinburne. The remainder of Solomon’s career is one of the minor tragedies of the Pre-Raphaelite story. Made a complete social leper by the strength of the Victorian moral code, he steadily gave way to drink and dissipation, ending his days an alcoholic in the St. Giles Workhouse in 1905. During his last years he supported himself by making drawings and pastels.

Some of Solomon’s images are remarkable for their androgynous quality. Among other things, his work illustrates very well the transition from PreRaphaelitism to Decadence. Current interest in gender and sexuality has brought his work forward for serious attendion by a number of critics. See, for example, the Simeon Solomon Research Archive: .

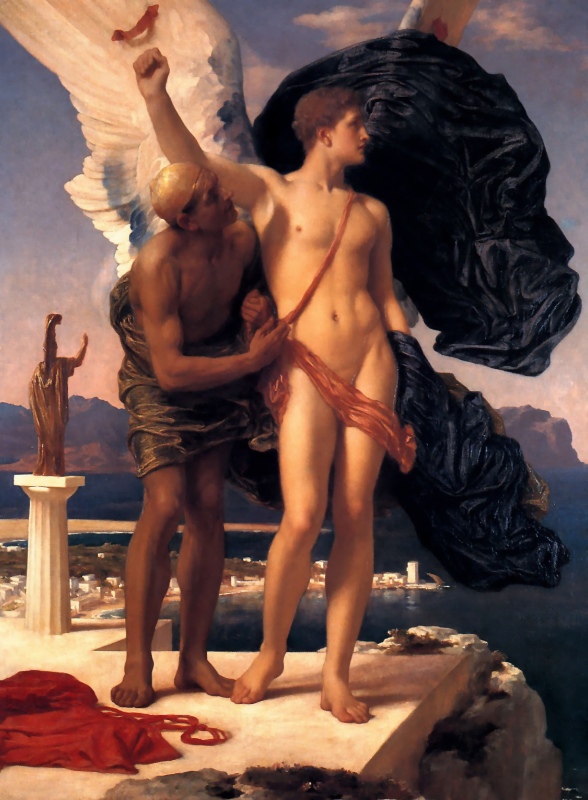

Slide 14: Leighton, Dadalus and Icarus

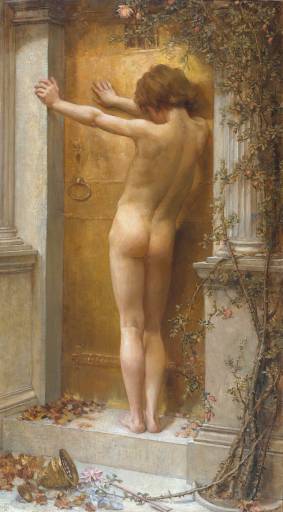

Slide 15: Merrit, Loved Locked Out

Anna Lea Merritt (1844-1930), Love Locked Out

http://www.artrenewal.org/asp/database/art

Anna Lea Merritt was born in Philadelphia in 1844, the daughter of Joseph Lea a manufacturer. She studied art in Italy, Germany, and Paris, ultimately settling England in the late 1860s. She married Henry Merrit, artist, and critic, who was twenty two years her senior. Tragically he died three months after the wedding. Anna Merritt edited a selection of her husband's writings for publication. She built up a thriving practice as a portrait painter, in which artistic sphere she was highly talented – her picture of two little sisters, Jacqueline and Isura Loraine, for example is highly accomplished. In later years she often wintered in Egypt. She lived in Hampshire.

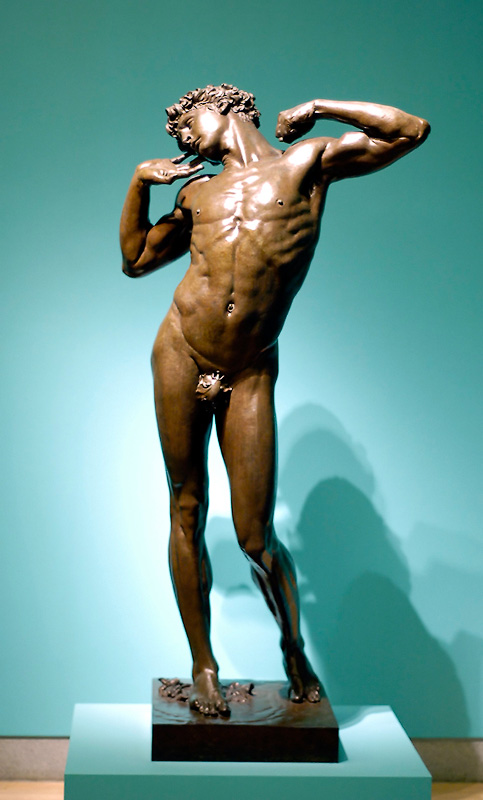

Slide 16: Leighton, Man with Python

‘Athlete struggling with a python’ 1877 (this cast 1910) Frederic Leighton (1830 – 1896) Bronze

also see Leighton’s The Sluggard.

Slide 17: Leighton, The Sluggard

Slide 18: Couture’s Romans of the Decadence.

It would have been recognized at the time as a collection of ideal nudes.

Slide 19: Poynter, Catapult, 1868

Director of the Slade. The male nude still has an iliac crest.

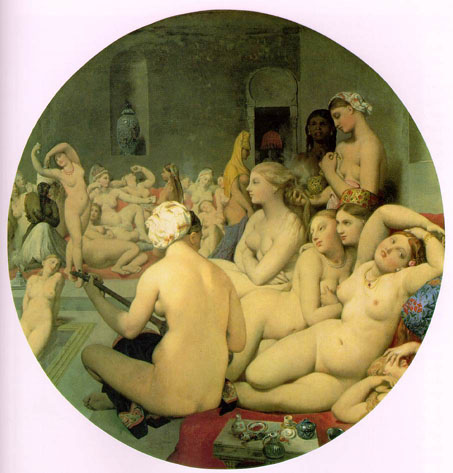

Slide 20: Ingres, Turkish Bath, 1862

Ingres, Jean Auguste Dominique

The Turkish Bath

1862

Oil on canvas on wood

Diameter 42 1/2″ (108 cm)

Musee du Louvre, Paris

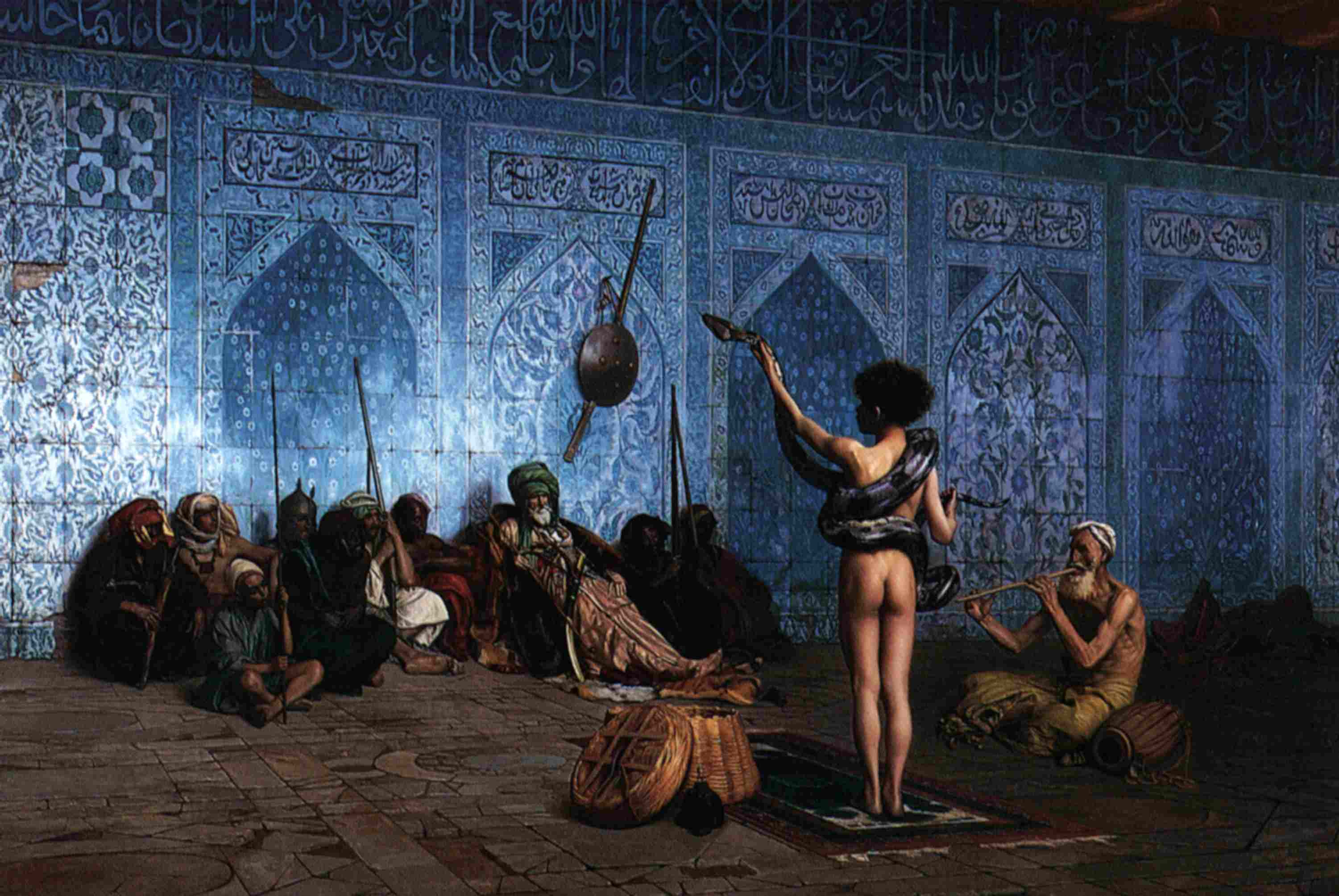

Slide 21: Gerome, Snake charmer

Jean-Le'n G'r'me, France, 1824-1904,

The Snake Charmer, French 1824-1904 Oil on canvas,33 x 48 inches

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown Masschausets USA

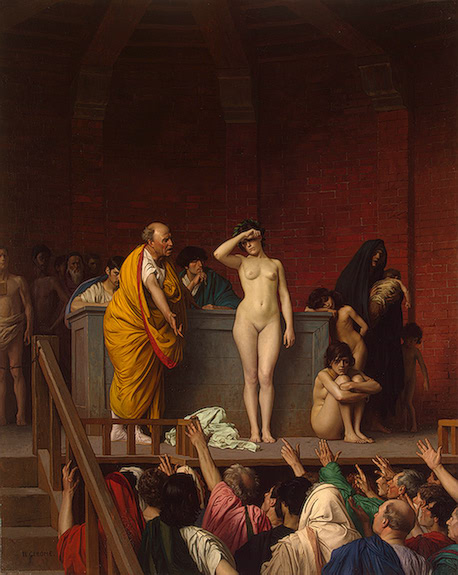

Slide 22: Gerome, Slave Market

The Commodified Nude

Nudes proliferate as they sell well and dealers demand them as capitalism expands.

Photography was first used for “art” studies, urban markets and pornography.

The above nudes were painted according to the rules of the academic nude. They are smooth and idealised with no pubic hair.

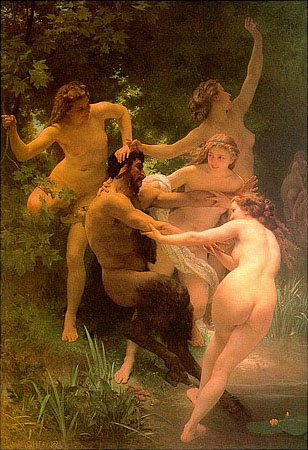

Slide 23: Bouguereau, Nymphs and a Satyr

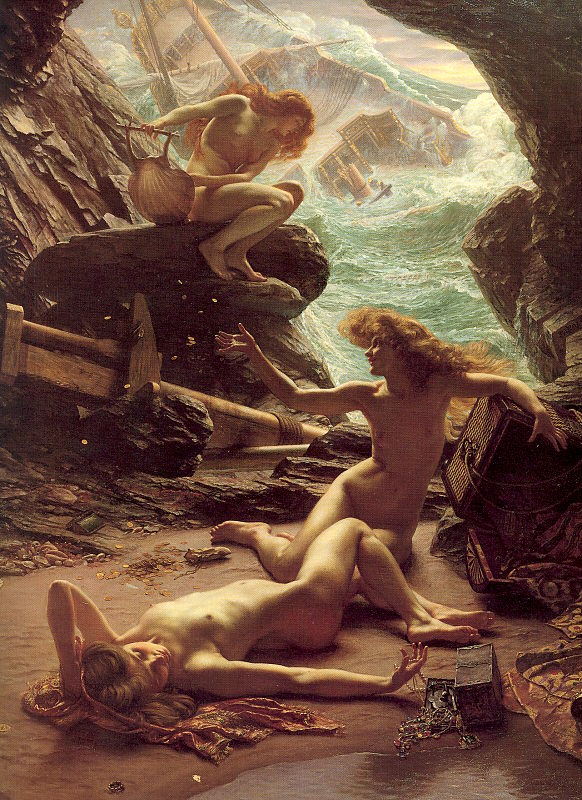

Slide 24: Poynter, Cave of the Storm Nymphs

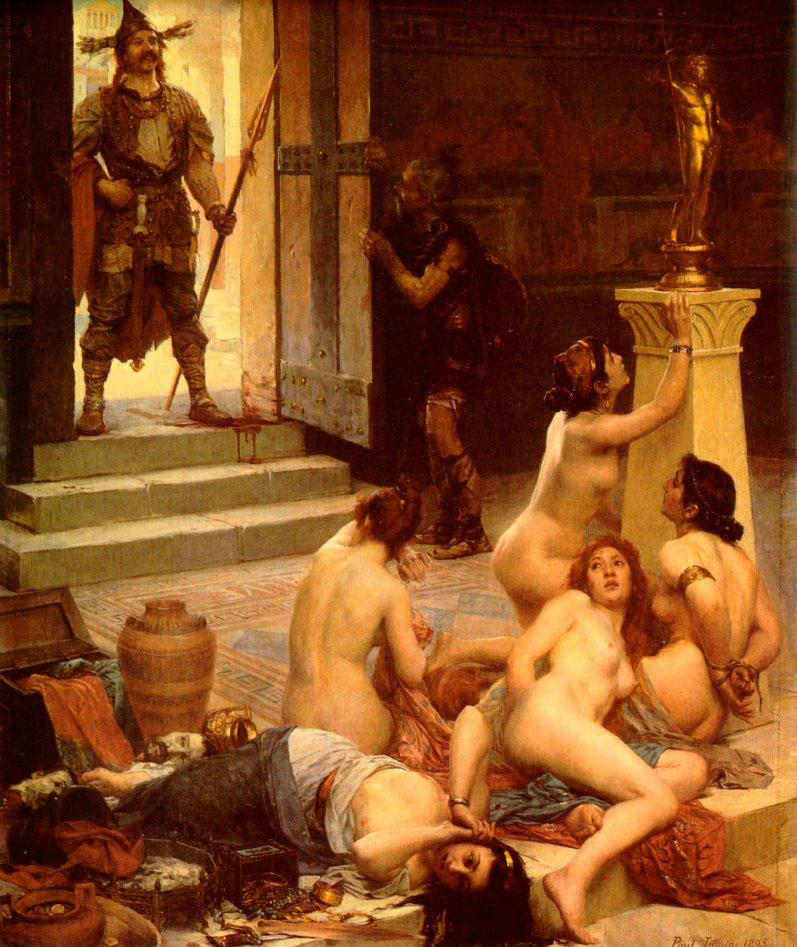

Slide 25: Jamin, Brenn and his share of the plunder

Paul Jamin (1853-1903), academic classicism

Le Brenn et sa part de butin Translated title: Brenn and his share of the spoils

Oil on canvas

63.78 x 46.46 inches / 162 x 118 cm

Private collection

Slide 26: Gerome, Pygmalion and Galatea, 1882

The Problem Nude

Slide 27: Carpeaux, Dance, 1869

Sculptor. Allegorical nudes to decorate the Opera Houses but they caused controversy as seemed too real. The women are moving and this was too disturbing. You can see folds of skin, cellulite and this was regarded as too real.

Slide 28: Millias, The Knight Errant, 1863

She is fleshy and specific in a real landscape. In 2008 there is a Millias retrospective at the Tate. Originally she was looking at him but it was too much of a “come on”. Millais repainted her head to lok away and dressed her in filmy gauze. (Was there a Millais model who went out to save people in a shipwreck?)

Compare with Leighton’s Deadulus. Leighton’s was successful but Simeon Solomon’s Bacchus was not. Bacchus was a problematic male nude. It was not accepted, later he was arrested and ended up in a poor house. It is a “puder” pose, androgenous. Homosexuality as a word came into use at this tine to draw a line between the homosocial (Leighton) and the homosexual.

See Nead’s “general structures of belief” quote on page 7.

The Modern Nude

Cabanel provoked Manet to paint a statement through the body of the women. Started in 1863.

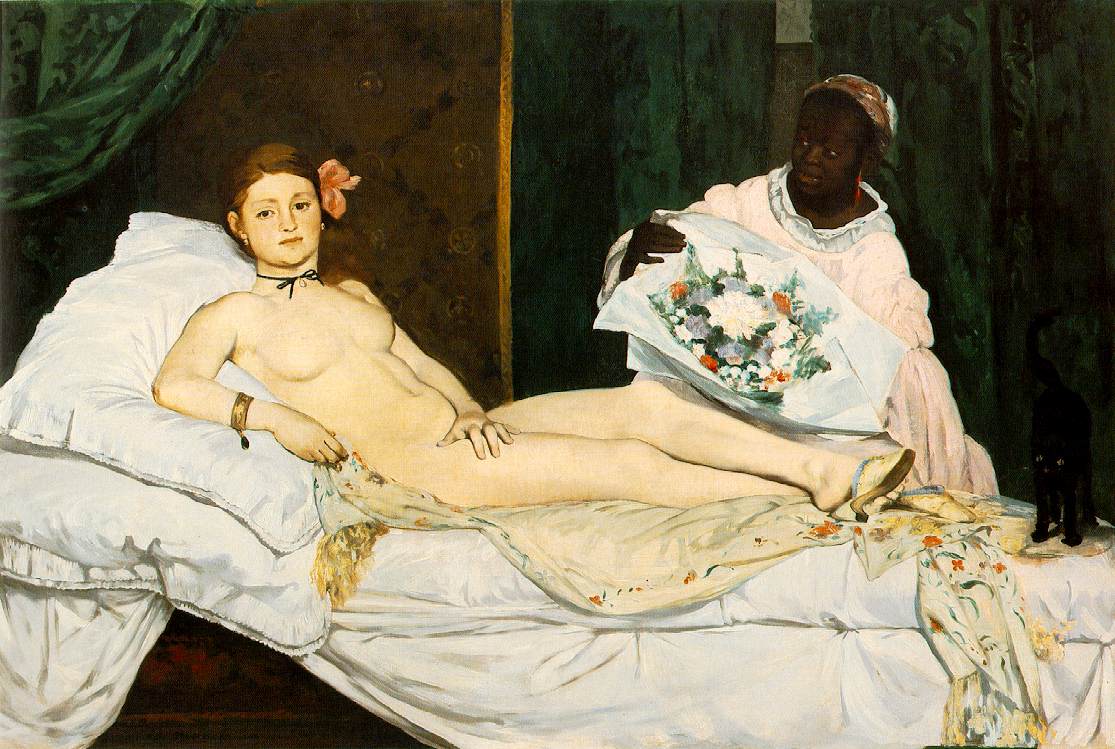

Slide 29: Manet’s Olympia

The painting creates an “economic relationship”. We see a closed room. Looking is a complicated, imprecise process and this is conveyed by the painting. Note the curtains cover a high window, is this a basement?

A hero of Baudelaire was Edgar Allen Poe. Baudelaire was the first to translate him into French. In the modern world we have an uneasy, contingent relationship with the world. It is not like a little village where everyone knows everyone. In the city we must judge people quickly and we need signs to do this. We judge by looking at their appearance, their clothes etc. In a sense we all become detectives. One problem with the modern world is that an ordinary women could wear the clothes of on duchess. This is unnerving as it undermines our ability to judge people and this uncertainty is also an aspect of the modern world.

Olympia is about a new visual relationship with the world.

Why was Manet so shocked by the scandal? Other people were doing similar things before this, for example, Awaking Conscience caused shock ten years previously in London. One important point is that prostitution had become a particular, publicised problem at this time in Paris. Also critics tend to pick on one work of art as representative of a type and Manet was seen to be the leader of a group of radical new artists. I am not sure this is a correct analysis of Olympia. Olympia differs from other paintings mentioned as it does not appear to be making a positive moral point (like Awakening Conscience or Romans of the Decadence). It appears to be amoral or even immoral as the “prostitute” looks straight out without shame, she is confronting society on equal terms and not hiding or flinching from what she is.

Couture’s painting was also about prostitution and how it brought down Roman society through decadence.

Note the shawl under her used to be a status symbol (see Ingres) but by 1865 it was a sign of being a “tart”.

Is Baudelaire snobbish about a shop girl being able to dress like a duchess? Reread his article as I don’t think “snobbish” correctly reflects his view.

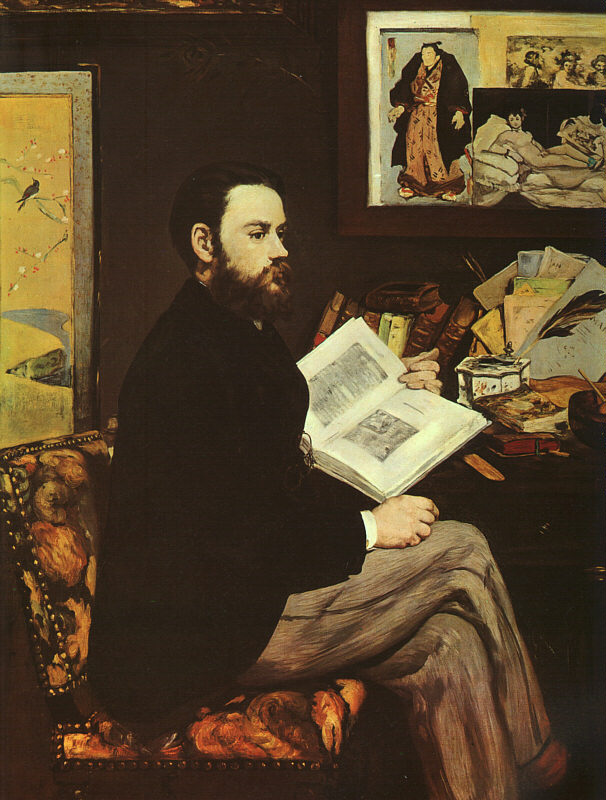

Slide 30: Manet, Portrait of Zola

Slide 31: Manet, Nana

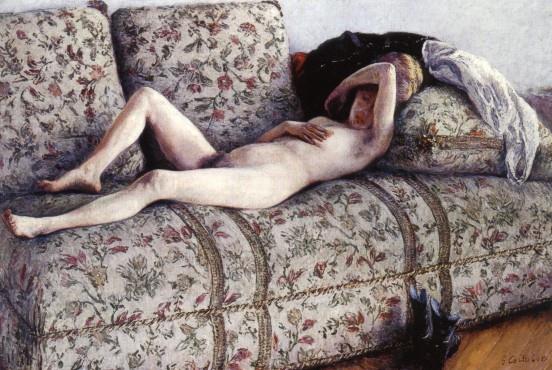

Slide 32: Caillebotte, Nude on a Couch, 1882

This is a very modern looking nude, sprawled on the couch rather than posed and shown with pubic hair. It is momentary and contingent. This nude looks like a modern painting, what does this mean? It is not a timeless, classical nude but in a sense it is “timeless” as we see it as modern over 100 years later, whereas we see classical nudes as old-fashioned. The concept of timelessness needs further exploration. When we call a classical nude timeless what do we mean? Do we mean that our society recognises a Greek nude as a thing of beauty and as it is so old we call it timeless? Would another society see it as beautiful?

Nead “takes apart” Kenneth Clark’s book on the Nude. It is written as “the nude for connoisseurs”. It tries to construct a sexually neutral form of nakedness called “the nude”. He tries to turn the naked person into an aesthetic object.

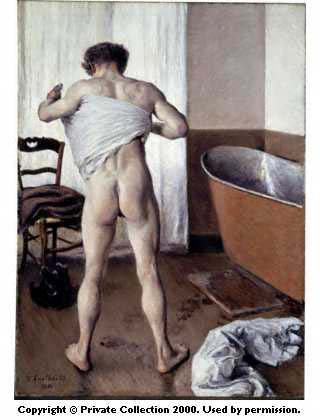

Slide 33: Caillebotte, Man at his Bath, 1884

Man at his Bath

1884

CAILLEBOTTE, Gustave

1848 – 1894

L670. On loan from a private collection.

Signed and dated.

This picture may have been inspired by Degas’s scenes of women bathing, but the subject of the male nude in an ordinary domestic setting is unusual in 19th-century art. Details like the wet footprints, the heap of clothes and the reflections on the metal bath-tub emphasise the banality of the setting.

Such a frank, voyeuristic portrayal of the nude form was potentially shocking to a contemporary audience, and when the painting was first exhibited in Brussels in 1888, it seems to have been shown in a separate room.

Oil on canvas

144.8 x 114.3 cm.

Note the wet footprints, the scattered towel on the floor. We even see testicles. The question “was Caillebotte gay?” has been raised.

The Primitive Nude

Slide 34: Degas, The Tub, 1886

Edgar Degas 1834-1917 BACK

The Tub

1886

pastel 60x83cm

Musee d’Orsay

Degas painted a series of nudes for the alst Impressionist exhibition. A series of pastels. They look spontaneous as they are so fresh but we know that they were the result of constant reworking with different poses over and over again. Note he includes her hairpiece on the sideboard. The modern women is literally made up.

See the book “Dealing with Degas”.

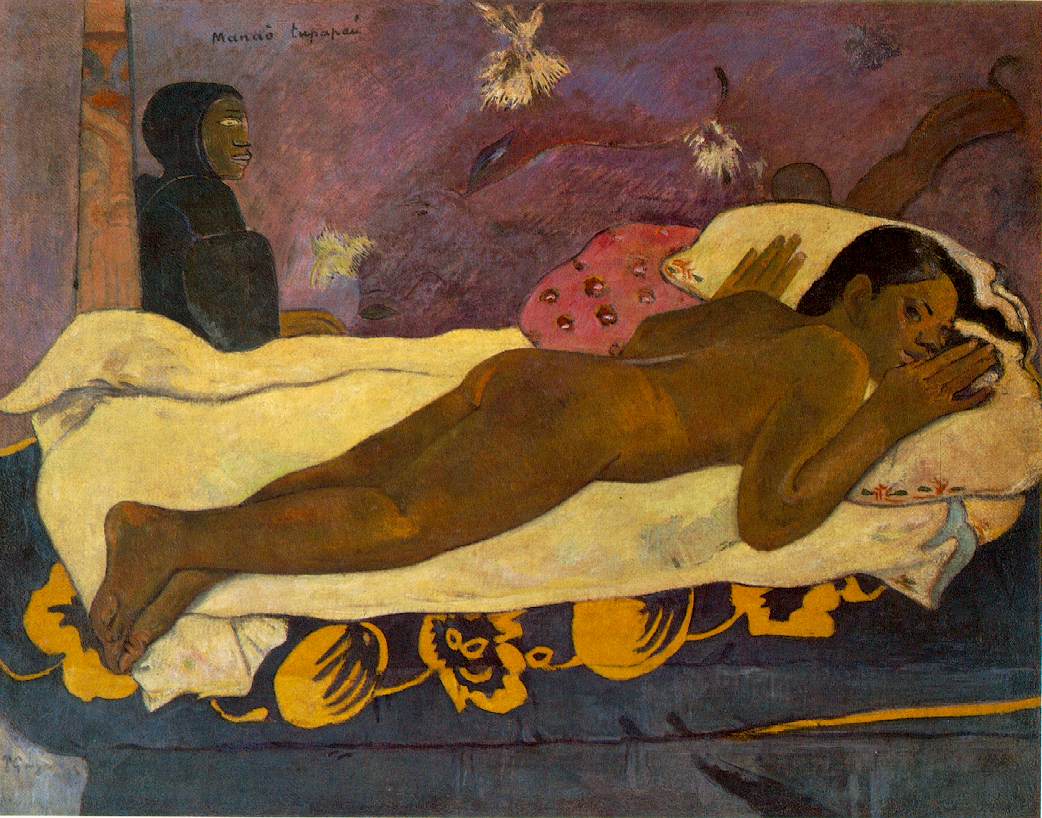

When dealing with Primitivism I would like to start with this image. Who are we being made into with these nudes? Are we a voyeur looking through a keyhole? Degas described the women as “like a cat licking herself”. Is primitive women alluded to? Another strand is the nude as an aesthetic configuration of colour and line. The woman’s back is simply a beautiful line like the line of the jug, complimented by the sweeping line of the bowl. A platonic shape, the painting can be seen as form, colour, shape, and line only. But it can also be seen as primitive. So the painting holds an ambiguity between the primitive and the aesthetic.

Slide 35: Paul Gaugin, The Spirit of the Dead Watching, 1892