This page discusses the origin and function of the portrait miniature, leaving most of the work of Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619) and Isaac Oliver (c.1516-1617) to the following two pages and Elizabethan painting.

Portrait miniatures were not originally painted on enamel — that came much later. At first they were painted in watercolours onto vellum then stuck onto card. Very reminiscent of manuscript illumination. Watercolour gave the transparent effect but for a more opaque look they used gum Arabic or glair.

They’re not called miniatures because of their size. Isaac Oliver’s miniature of the Earl of Dorset, (2) for example, in the V&A is A4 size – it’s called a cabinet miniature (because that’s where they were usually displayed). It comes from the Latin word ‘minium’ meaning red lead which was the colour painters used for the important parts in manuscript illumination texts – the capital letter in particular — hence the expression ‘red letter days’ in common use today.

The other point to take on board is that the term ‘miniature’ was not recognised until the 17th century. The Tudors used the term ‘limning’ from the word ‘illumination’ for all manuscript illumination and portrait miniatures. Nicholas Hilliard, for example, wrote a book entitled The Art of Limning.

The earliest miniature seen in the UK was during Henry VIII’s reign in the 1520s. The style and technique was developed in the Flemish workshops of Ghent and Bruges. The Flemish had left the French way behind in pursuing and developing this area.

Simon Bening, Gathering Twigs, c. 1550

(3) Munich Monsterat Haus (Mansoat) c.1535-40 by Simon Bening (c.1483-1561). A very important Flemish manuscript illuminator. Landscape watercolour. Then wash applied to give it aerial perspective.

(4) Simon Bening’s Self-Portrait 1558 (V&A). Clues to his profession:glasses, for close work. Natural light. Book propped up, not flat. There’s no evidence to suggest that these manuscript illuminators/portraitists needed much magnification, though and many worked into old age. They dressed v plainly. NB the hat — worn indoors either to keep warm or to keep everything around them clean — it wouldn’t do for any loose hairs, for example, to drop onto the delicately- painted miniature whilst it was drying … His daughter, Levina Teerlinc was also an illuminator who came to London in the 1550s. She was a favourite of Mary Tudor and Elizabeth I. In England gifts were exchanged at New Year rather than Christmas and Levina gave Elizabeth an illumination every year for nine years.

Another great Flemish illuminator was Gerard Horenbout who worked for the Hapsburgs until he came to England in the 1520s and was on Henry s payroll from 1528-31. No-one is quite sure what he actually did, though. His daughter, Susannah, was also an accomplished illuminator and it is said that Dürer bought a few illuminations from her in 1521.

But it was his son, Lucas, (c1490-1544) who rose through the ranks at Henry VIII s court and was referred to as a Pictor-maker in accounts. He was at court from 1525-44. He was made the King s painter — as indeed was Holbein so this indicates that Holbein really wasn’t considered anyone special at the time. In fact Horenbout was paid more.

Few portrait miniatures are dated or signed, unfortunately, so historians have to try to match names to style of painting.

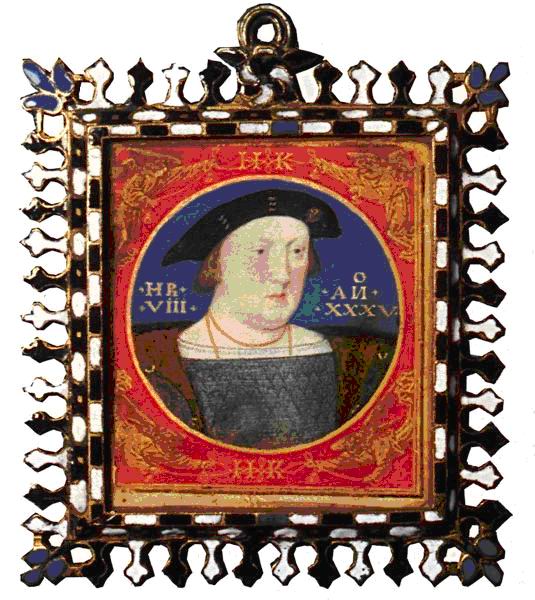

(1) Henry VIII 1525-7, was attributed to Lucas Horenbout as he was thought to be the only portrait miniaturist at the time who could have painted it. The angels in the corners are typical of Flemish decoration of the period. There is real gold on top of brown ochre paint, set against red. The face is painted by using an underlayer in a pinkish colour (known at the time as an opaque carnation ground). On top one can see the transparent properties of watercolour being used to build up the flesh tones and for light and shade. This is very typical of the Flemish tradition. This miniature is tiny: 53mm x 48mm.

(5).Lady With a Large Ruff, c1580s by Nicholas Hilliard. This is an example of an unfinished miniature by Hilliard — we don t know the lady s identity. Her body is bare vellum; the background is blue. One can’t see a single brushstroke — it’s flawlessly smooth. How does one get this effect?Water is applied to the vellum to dampen it. The pigment is then placed on the area and it spreads itself out — i.e. it applies itself. (1) is also a typical example of this. Other typical features:- round, blue background, gold rim, head and shoulders only. This technique is a standard approach in miniature painting until the 17th century. Portrait miniature was like ms illumination, therefore, but painted as a detached, separate portrait. It was used on jewels, cameos, coins, seals and medals.

(6) Portrait of a Man c1450 by Petrus Christus. National Gallery. Illuminated portrait showing an indulgence image. Christ, blue background, lots of gold. An early example of a portable portrait of Christ.

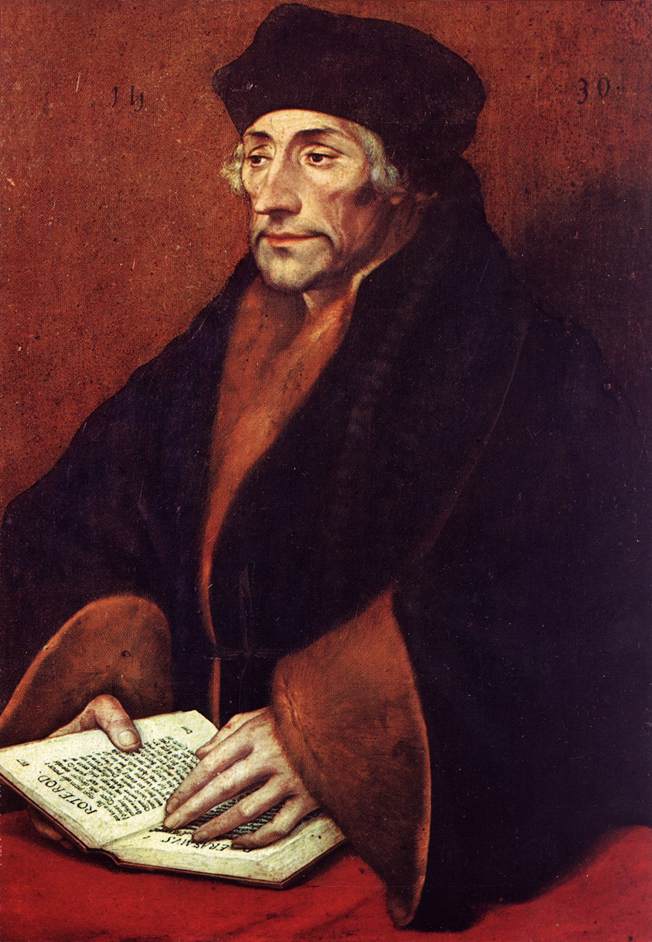

(7) Erasmus 1531-2 by Holbein. A small oil portrait in the round.

(8) An early Flemish example, Holford Hours 1526. unknown man with coat-of-arms.

When did portrait miniatures emerge? They were certainly in England and France before 1520. We’ve really no idea who invented them.

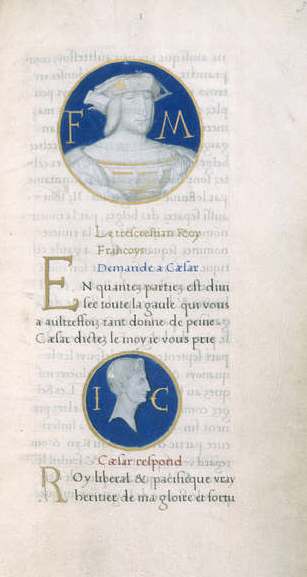

See (9), a double page spread from an illuminated manuscript, Les Commentaires de la Guerre Gallique Vol I1519-20 with illuminations by Godefroy le Batave. Commissioned by François 1er. The page on the right features a Caesar-like cameo with a similar example of François Ier above it. It s small, made to look like a medal almost. But we have a head and shoulders, three-quarters profile, blue background and gold — more or less a portrait miniature. It’s thought to have been done like that to flatter the king — comparing him to Caesar.

(10) Vol 2 of the same ms, this time illuminated by Jean Clouet. Date thought to be 1520. Here we have portraits of some of François Iers generals. Allelements of these portraits lead to the fact they were early miniatures — round, blue background, use of gold etc. See also (11) Clouet s Odet de Foix, compte de Lautrec. (check this out — was a chalk drawing — became an illumination later?)

(12) This is a Letters Patent, 1524-8, granted to Thomas Forster, thought to be illuminated by Lucas Horenbout. It is a typical, large document with an elaborate seal. We see a portrait of Henry VIII, surrounded by a large gold letter H. It contains all the elements of portrait miniature.

(13) Mrs Jane Small c.1540 by Holbein. She was the wife of a London merchant. V reminiscent of his The Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling 1526-8. Beautifully executed. Blue background; gold frame. — playing card image on reverse. Only a small no. of extant portraits have their original settings.. Much more sculptural compared with (1). More 3D, too, which is to do with the way it is painted: Horenbout is an illuminator; Holbein is an oil painter. Horenbout works up the surface of the face by applying the paint in flat, angled strokes following the surface plane of the picture. Holbein makes the strokes follow the contour of what is being painted — for the chin, for example, the strokes curl round. In the Holbein more of the body is in the portrait — it s more than half-length. NB the hands in Holbein’s — they look much more like in an oil painting than in a portrait miniature.

(14) Henry Strangwish by Gerlach Flicke. Subject of a presentation on 11th January 2007.

(15) Catherine Greyc.1558-60 by Levina Teerlinc. Horenbout’s daughter. Her miniatures characteristically portrayed people with tiny arms – as here.

(16) Maundy Ceremony c.1560 by Levina Teerlinc. A portrayal of the event whereby the Queen washes the feet of the poor and gives them money. The ceremony is traced back to Jesus and his disciples — sign of humility. NB the cast of thousands given this is such a small miniature — the height of this one is no bigger than the palm of one s hand. Choirboys, guards, pensioners, common people — all are clearly delineated. Fascinating as a social document.

The Function of Portrait Miniatures

In the 16th century there was an increased interest in large scale portraits and miniatures.. So what is it about portrait miniatures which differentiate them from oil painting?Firstly, their portability — they can easily be carried about the person. Secondly, you can choose who sees it — it can be a public or private object. Thirdly, they were often used in illicit relationships they could be secreted about the person or closed up if they were being used in a locket, for example.

(See “Secret” Arts: Elizabethan Miniatures and Sonnets, Patricia Fumerton, Representations, 1986)

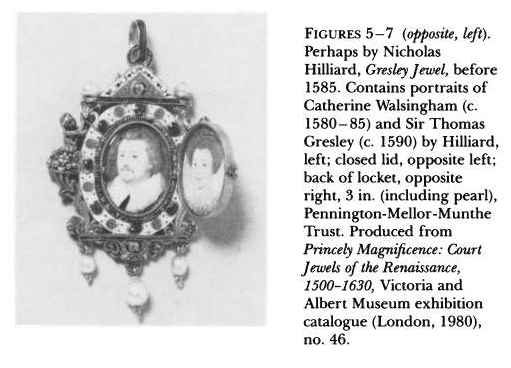

(17) Gresley Jewel 1585 by Isaac Hilliard. Intact and stunning. On one side is a cameo of an African lady surrounded by gold, precious gems, enamel and pearls. Ring at the top for a chain or a ribbon. On the other side is enamel foliage set into gold with gems. This is a locket which opens to reveal a double portrait.

(18) Unknown Manc.1600 by Hilliard.

(19) Lord Herbert of Cherbury 1613-14 by Isaac Oliver. This miniature was made after the oil painting.

(These notes are thanks to Lesley Toll)