The Pre-Raphaelite body comes in many guises:

- The Ideal Body

- The Material Body

- The Diseased Body

- The Mortal Body

- The ‘Primitive’/Ascetic Body

- The Oriental Body

- The Resurrected Body

- The Composite Body

- The Fetishised Body

- The Aesthetic Body

- The National Body

- The Fragmented Body

In many ways the body is central to the the ideas surrounding the

Pre-Raphaelites. See The Pre-Raphaelite Body, an article on the Victorianweb.

‘In each of its phases the debate about Pre-Raphaelitism was staged around

the representation of the human body’ J. B. Bullen, The Pre-Raphaelite Body (1998) [1]

Also Nochlin, The Body in Pieces, Prettejohn, Beauty and Art, Nead, Myths of Sexuality (especially the section on prostitution and disease), Prettejohn, The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites, exhibition catalogue (Chapters 7 and 9) and the recent collection of essays on G. F. Watts and the body.

We must consider the idea of the post-Romantic, post-industrial individual.

Anatomical Naturalism

Studies of the body itself and scientific or pseudo-scientific approaches to understanding and representing the body.

- Hogarth, Analysis of Beauty, 1753

- Sir Charles Bell, Essay on the Understanding of Expression in Painting,

1806 - Phrenology, Combe’s The Constitution of Man, 1828, Robert Chambers,

Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, 1844 (a popular science book

that proposes the idea of evolution although this idea was first proposed by

Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, in 1794-6, Darwin’s key step was his

work was founded on observation not speculation and it included the ideas of

variation and selection) - Royal Academy life drawing

Books on drawing and the human expression stylized races, for example, the ‘typical’ Welsh face was compared to the ‘typical’ Negro face, each region of Britain was illustrated by its ‘typical’ racial type.

Life Drawing

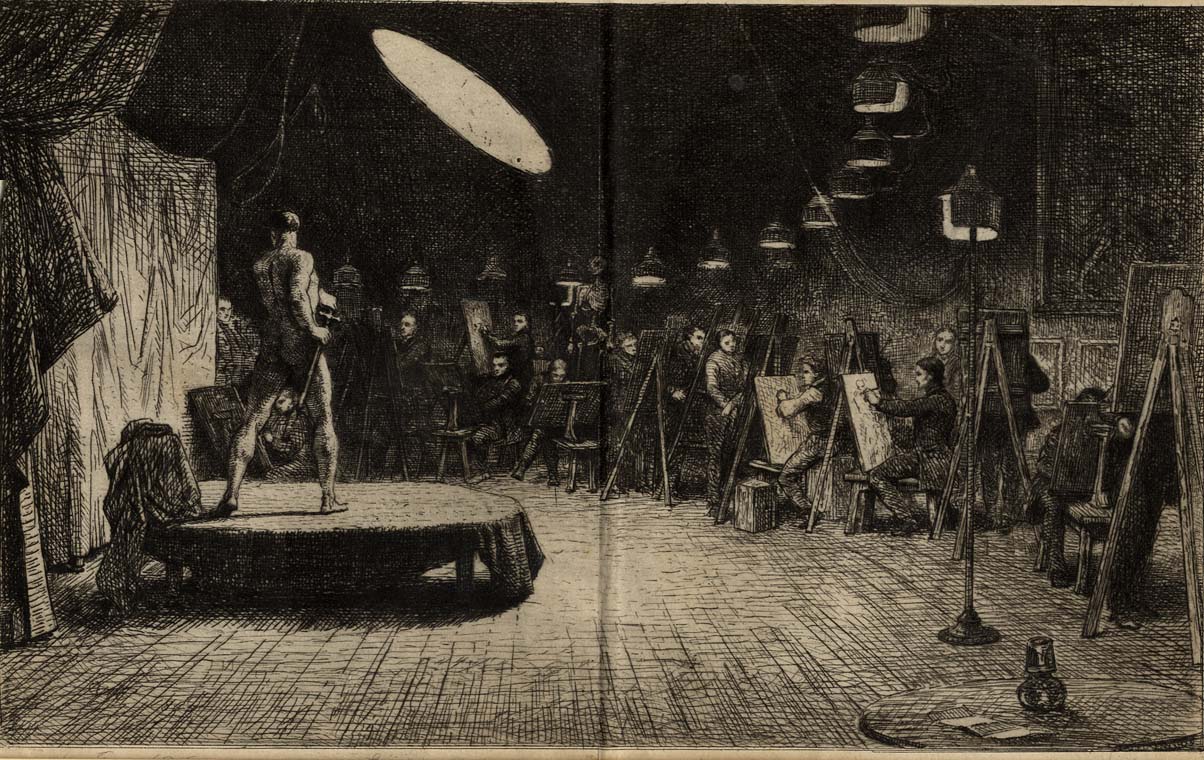

Royal Academy, life drawing class, C. W. Cope, showing drawing took place by artificial light.

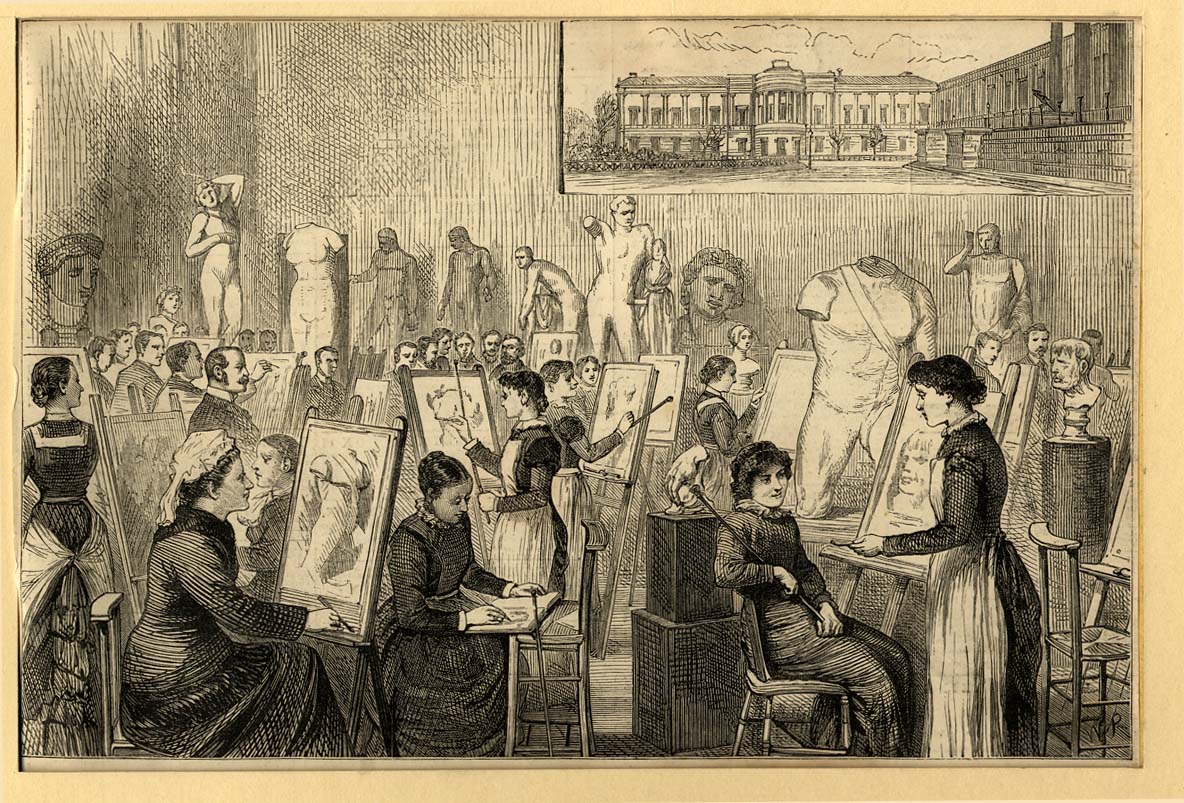

Slade School, drawing class, from the Illustrated London News, c. 1880. Note that the female students are drawing from plaster casts not from life.

William Holman Hunt, life drawing (not found)

Jenny (1st 4 lines)

Lazy laughing languid Jenny,

Fond of a kiss and fond of a guinea,

Whose head upon my knee to-night

Rests for a while, as if grown light

Rossetti Sonnets: 1870

For the complete poem in Poems. A New Edition and a facsimile of the

1881 edition see the Rossetti Archive.

Portraiture

Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893), The Pretty Baa Lambs

The model was Brown’s wife. In 1841 he had married his cousin Elizabeth Bromley, who died of consumption in 1846, leaving a daughter, Lucy, who in 1874 became the wife of William M. Rossetti. Not long after being left a widower, Brown took a second wife, Emma Hill, who figures in many of his pictures including this one. She had two children who grew up: Catherine, who is the baby in this painting, and who married Dr. Franz Hueffer, the musical scholar and critic, and Oliver, who died in 1874 in his twentieth year. All three children showed considerable ability in painting. The second Mrs. Brown died in 1890.

The question is whether the painting is a portrait of his wife and child? It balances between a portrait and a narrative painting. In the past figures in paintings were idealised and although based on a model were generalised from the model who could not be recognised. The Pre-Raphaelites painted an actual person (or they sometimes constructed a body from multiple models, each painted from life). This created a strange effect and critics could not handle what was going on.

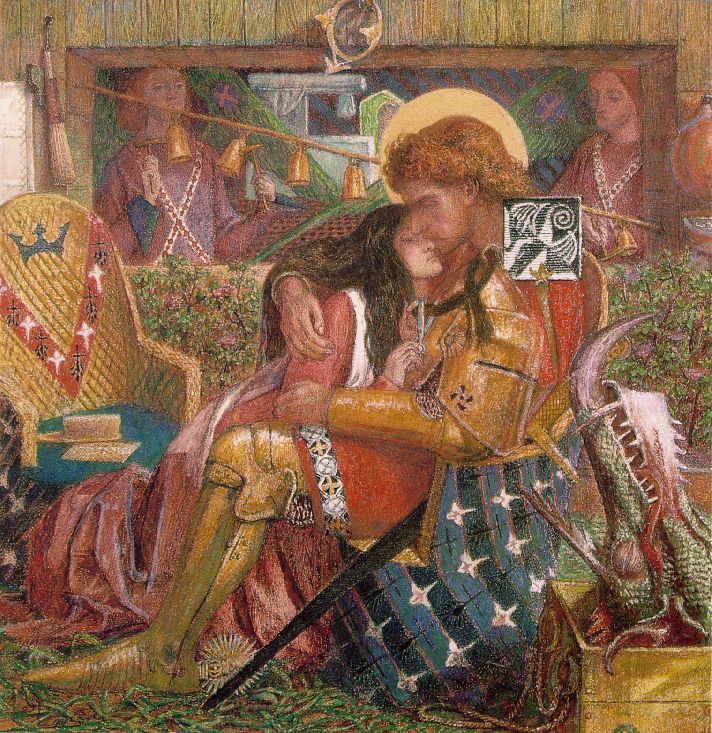

Hunt, Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus, 1851

Hunt used Lizzie Siddal as the model and Proteus was modelled on a student who became a lawyer. Hunt mentioned in his autobiography about the student becoming a lawyer which suggests he thought the right type of person was important in each role.

The brother in Millais’s Isabella was a student who used Millais’s hair as a floor broom when he was younger (as he was the youngest student at the RA he was often persecuted), Millais had become friends with the student by this time.

This technique of painting from life creates a completely new vocabulary and compares with, for example:

Charles Eastlake, The Escape of Francesco Novello di Carrara with his Wife, 1850

The figures in this painting (as in most paintings, other than portraits) were generalised. How many times have we seen similar figures? Each was painted as a type, the hero, the heroine, the villain and each type was represented in a particular way with a particular facial type. In this way the viewer could read the painting and recognise each type and therefore work out what was going on.

In Hunt’s painting every detail is specific, each eyelash is painted from life, some short, some long. Every hand is a painting of that person’s particular hand, blemishes and all.

The painting of blemishes is significant. Pre-Raphaelite pictures of plants have been compared with botanical paintings but botanical paintings illustrate a species rather than a specimen so a perfect specimen is selected and blemishes are generally removed as they are not indicative of the type. In Millais Ophelia the rushes on the left are painted broken with broken marks, we can see he painted the particular reeds in a particular river.

The Pre-Raphaelites also created new poses. Compare the Eastlake, how often have we seen a woman sitting on a horse that way. Now look at Julia slumped against the tree, a very unusual pose as she turns Proteus’s engagement ring on her finger behind her back (or possible she is removing it).

Ford Madox Brown, Last of England, 1855

Brown posed Emma in his back garden in January to see the effect of the cold and paint her watery red-rimmed eyes. It took him four days just to paint the red ribbon.

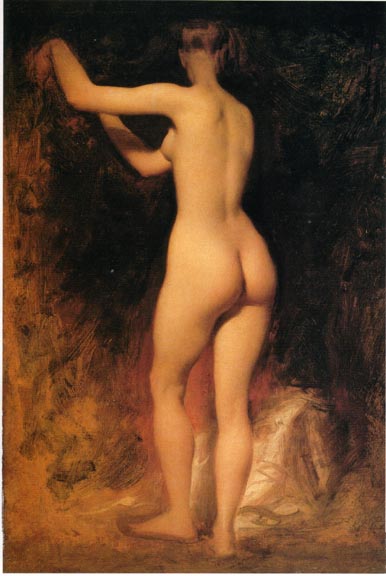

Does this explain why they did not paint the nude? Proprietary dictated a nude must be generalised and so it was difficult for the Pre-Raphaelites to paint from life and be exhibited. It is possible Hunt did sketch the nude and Hunt and Millais would have all sketched the nude (probably male) at the Royal Academy School.

The girls were painted from life and some critics complained ‘why didn’t he paint someone pretty.’

Hunt, A Converted British Family sheltering a Christian Priest from the Persecution of the Druids, 1849-50

The figures were painted from life. The boy, for example, has the waxy, white skin of a London child that has not seen the sun rather than the sun-tanned, idealised figures usually seen. The figure in blue was a gypsy that Hunt found by advertising.

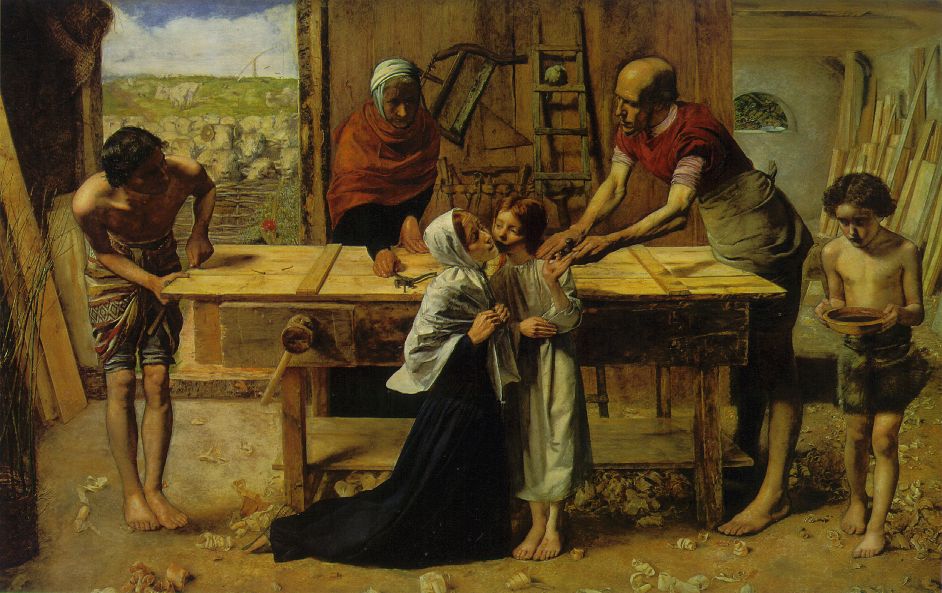

Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents, 1849

The painting was criticized for being wrong anatomically.

‘a hideous, wrynecked, blubbering, red-haired boy in a nightgown, who appears to have received a poke … and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness, that she would stand out from the rest of the company as a monster.’

Charles Dickens, on Christ in the House of his Parents, in

Household Words 1850

‘We have now in London pre-Raphaelite painters, pre-Raphaelite poets, pre-Raphaelite novelists, pre-Raphaelite young ladies, pre-Raphaelite hair, eyes, complexion, dress, decorations, window curtains, chairs, tables, knives forks and coal-scuttles. We have pre-Raphaelite anatomy, we have pre-Raphaelite music,‘

American journalist (Justin McCarthy Galaxy Magazine) 1876

The figures were described as ‘sick’ and ‘diseased’, similar to the reaction Manet received when he exhibited Olympia in 1865. They were described as too skinny and as having rickets. They also found it difficult to separate morality from disease. That is, the immoral was considered diseased. See Sontag, Illness as a Metaphor.

Ford Madox Brown, Work, 1852-63

Brown uses new figures type that some critics saw as like Michelangelo but they are not as they have specific rather idealised faces.

The Material Body

Raphael (1483-1520), Transfiguration, 1517-c. 1520, oil on wood, Vatican Museum

The Pre-Raphaelites were troubled by the boy in the bottom right as they compared him with the pictures in Bell’s book and thought he was having a fit but in that case he ought to be grimacing more and his limbs are wrongly positioned. In other words that subjected the picture to anatomical analysis.

The Christ figure and Mary seem to copy the figures at the bottom right of the Raphael. The Pre-Raphaelites replaced generalised bodies (Reynolds term) with the material, anatomical body.

So, what happened to beauty? Raphael was the extreme example of beauty until the Pre-Raphaelites raised this question. Are they creating an aesthetic of ugliness or a new type of beauty based on actual people rather than idealised people/

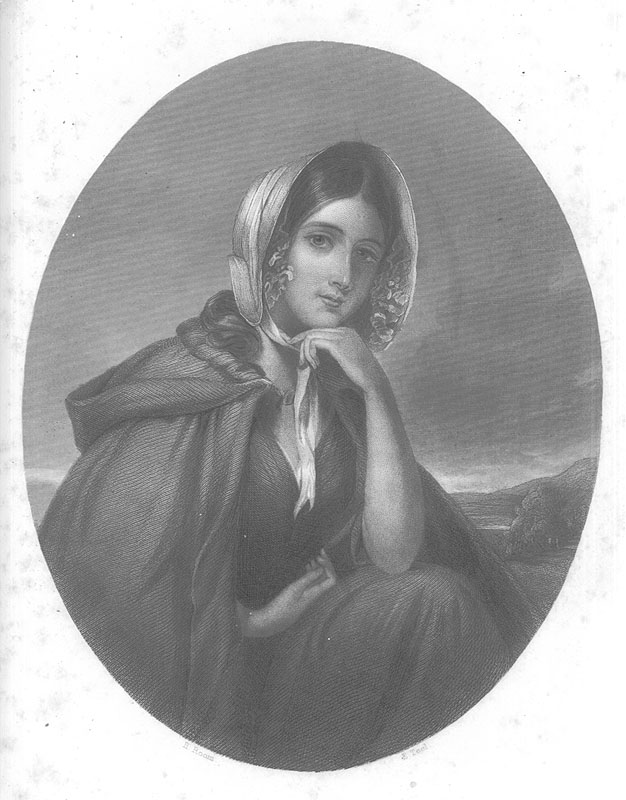

We can compare the Pre-Raphaelites with Keepsake beauties.

Unknown artist, etching from ‘The Keepsake’, 1854

Such images were from the women’s magazines of the period and were also hung on the wall. Sentiment, which we dismiss as shallow and trivial was highly regarded by the Victorians. Kant discusses beauty of his Critique of Judgement. Compare the following two Hunt pictures that illustrate beauty in different ways.

Hunt, The Afterglow in Egypt, 1854-63

Hunt, Isabella and the Pot of Basil, 1876

The Mortal Body

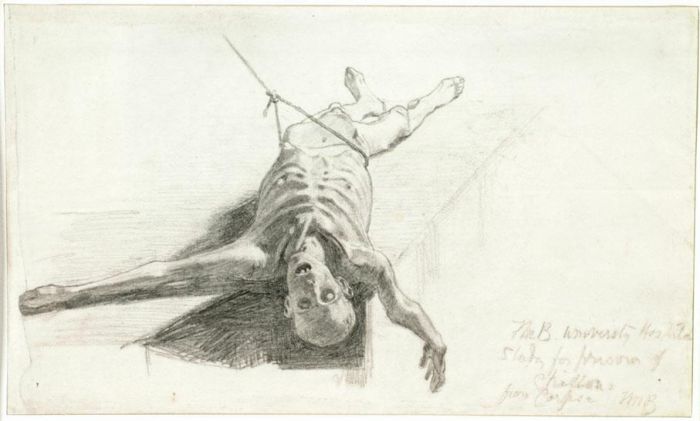

Brown, The Prisoner of Chillon, 1856

A shocking, vulnerable, mortal body showing death.

Millais, The Artist Attending the Mourning of a Young Girl, c1847

A little known work by the young Millais who was asked to portray a young girl who had recently died.

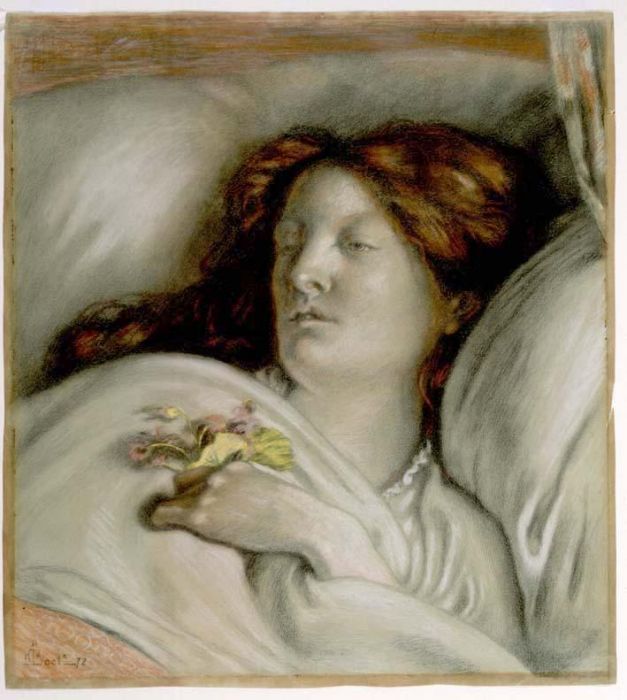

Brown, Convalescent Portrait of Emma Madox Brown, 1872

It is possible Brown thought his wife was going to die but she recovered. Over 50% of photos in the late Victorian period were of the dead so that they might be remembered by their loved ones.

Holman Hunt was a hypochondriac and often wrote of death.

- ‘the shrunken but beautiful body’, Hunt, letter about his dead wife Fanny

- ‘my eyes sank so deep into my head, and I became green, and my body

seemed such a heavy, stiff; unelastic corpse’, Hunt, Letter about his own illness

Hunt’s preoccupation with the dead body started after his wife’s death. Isabella and the Pot of Basil is based on his dead wife, note the appreciation of her body shown through her nightdress. Hunt was also preoccupied with nightdresses, he wrote of his second wife coming into his room in her nightdress.

The Resurrected Body

repetition can be seen as an attempt to counteract absence, loss and death…[A]s a double of the lost object, the first object can return in a new form, thus questioning the uniqueness of the first term and implying that the loss is

not irrevocable’Elizabeth Bronfen ‘Risky Resemblances: On Repetition, Mourning and Representation’

The eschatological hope.

‘the physical absurdity of His body having been received into the

clouds’, Hunt

Hunt was referring to the Raphael Transfiguration above. He had clearly thought about the issues a lot and considered the physical body floating up into the sky to be absurd. He speculated about whether at death the soul leaves the body in the same way that water evaporates to reform later as clouds.

Hunt, The Triumph of the Innocents, 1883-4

An unusual image, note the extraordinary physicality of the babies who seem to be assembled from body parts that don’t quite fit. In fact Hunt had to paint them in parts as the babies wriggled so much. He joked that he had had to dissect the babies in order to paint them.

Compare with,

Brown, A Study of Arthur Madox Brown aged 9 months, 1856

The Fragmented Body

From Hunt’s Journal, Jerusalem 1872 of painting Christ in The Shadow of Death 1869-73

- 8 February – 7am bothered much about the head. ‘A long and minutely detailed

analysis of the expression and angle of the face follows, concentrating on the

open mouth. 7 work on in a fever to get it right.’ - 3 March — ‘correct my face’

- 16 March — changes the head again, although he has shown it to friends who

consider it already perfect. - 30 March — redesigns the head again.

- 7 April – feels ‘head is right for finishing’

- 12 April — alters the head.

- 17 April — scrapes back and renews the white ground on the head.

- 22 April — repaints the head.

- 26 April – ‘Touch a little.. . on the head bringing the line of the left cheek a

little further out, also the forehead’ - 2 May – ‘To get it [the head] ready for my final days painting make several

changes in drawing in little parts’. - 3 May – ‘shocked to find’ this ‘too extreme and too partial.., quite bewildered

about the head which looks right close but at a distance looks wrong I am quite

in despair’ - 6 May — renews the white ground and makes the head smaller.

- 7 May — decides that the head is too small, and makes it larger.

- 9 May — repaints most of the head.

- 11 May — repaints the face, ears and ‘expression’ which is ‘too painful’

- 18 May — feels he has almost finished.

- 21 May — repaints hair for a second time.

- 30 May — alters the head again.

- 1 June — finds that the ground has become sandy in texture and renews it.

- 6 and 7 June — repaints the head.

- 7 June — finds the cheek is still rough and redoes it.

- 9 June — finds ‘the head done but wanting a few touches’

- 11 June — amends ‘the contour of the cranium’

The painting took four years of intense work and this extract concerning the painting of the head indicates why. We have a sense of fragmentation rather than the ‘Holman’. He pulls the image to pieces, cuts it away, destroys it and then rebuilds it again and again, a pathological relationship of damage and repair.

Did he use photography? He never mentions it but it must be a possibility. He did use multiple models and even parts of his own body to finish the work.

‘I dare not look at yesterday’s work [the hair of Christ] but eagerly take advantage of the opportunity to work from Isaac to finish arms and body, begin at the rt hand and proceed downwards where am confronted by the hair I grow very unhappy admitting that it will never do’. Hunt.

The Pre-Raphaelites did tend to use composites, that is they painted their figures from parts copied from different people, a way of idealising without ‘cheating’. Similar to the tale of Zeuxis who, when asked to painted Helen for Crotona in Ancient Greece asked that the five most beautiful women of the city should pose nude for him so that he could select from each her fairest feature and combine them all to create a second goddess of beauty. Zeuxis was also the artist who was meant to have painted a still-life of grapes so perfect the birds tried to peck them.

Fanny was painted from a photograph and it shows as her expression does not look lifelike. Maybe it results from her glazed look from a long exposure photograph.

Hunt was working on three paintings at the same time, a self-portrait, his dead wife Fanny and her sister Edith, his future wife.

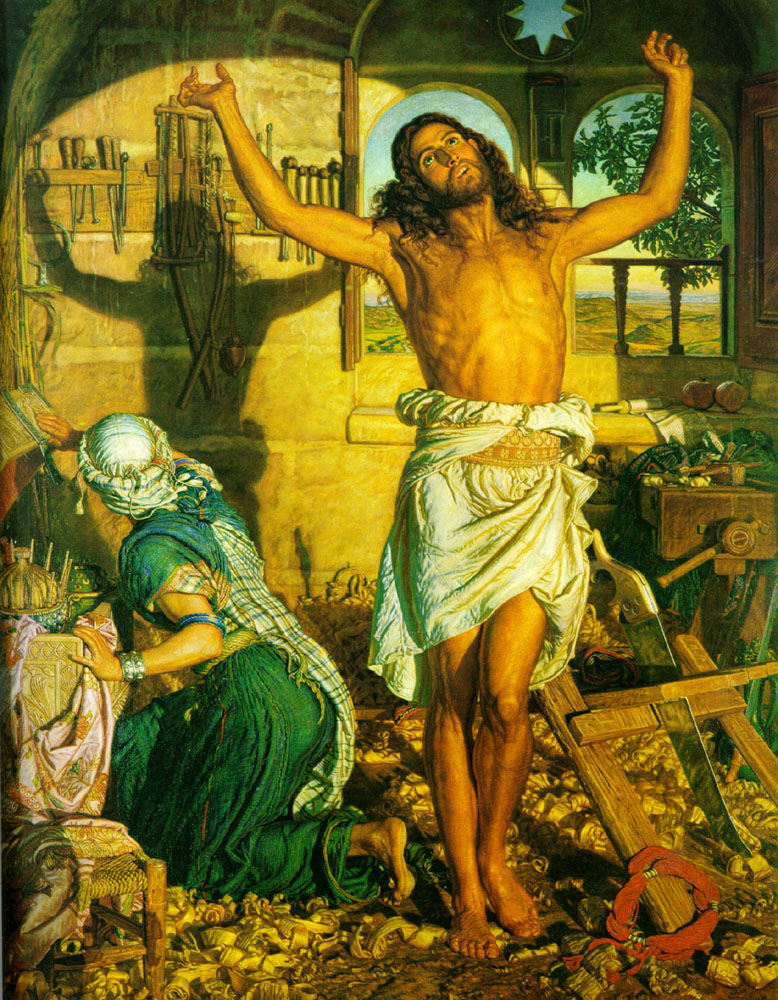

Hunt, Shadow of Death, 1870-73

‘surfaces as disturbingly broken to the gaze as the chaotic fragmentation of the harshly lit room’

Pointon ‘The Artist as Ethnographer’ on The Shadow of Death

‘that sense of social, psychological, even metaphysical fragmentation that seems to mark modern experience — a loss of wholeness, a destruction or disintegration of the permanent’.

We see a vulnerable body surrounded by sharp objects. When Hunt was young he drew a self-portrait surrounded by a ring of sharp knifes and he carried the drawing with him.

Hunt also sketched himself in Egypt showing himself awake while everyone else sleeps. In the text below the image he crossed out ‘Daddy’ and changed it to ‘Father’.

Hunt had a negative view of all organised religions. He though Christ was like an artist – honest, good and true and only God will save you.

But… it is by no means possible to assert that modernity may only be associated with, or suggested by, a metaphoric or actual fragmentation. On the contrary, paradoxically, or dialectically, modern artists have moved to wards its opposite, … the struggle to overcome… Disintegrative effects… by hypostatizing them into a higher unity. One might, from this point of view, maintain that modernity is indeed marked by the will towards totalisation as much as it is metaphorized by the fragment. [my bold]

L Nochlin, The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity (1995)

In modern subjects there is a search for wholeness which is what Hunt is trying to find. Note the bold sentence from Nochlin.

The ‘Primitive’ and Ascetic Body

The sharp body. Retzsch (‘retch’) was popular with the Pre-Raphaelites.

Moritz Retzsch, The Decision of Flowers, 1820

Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents, 1850, drawing

Note the skinny, angular figures, a response to fragmentation? A cut-up composition. In his painting of Isabella every figure cuts into the next with a light/dark or colour contrast.

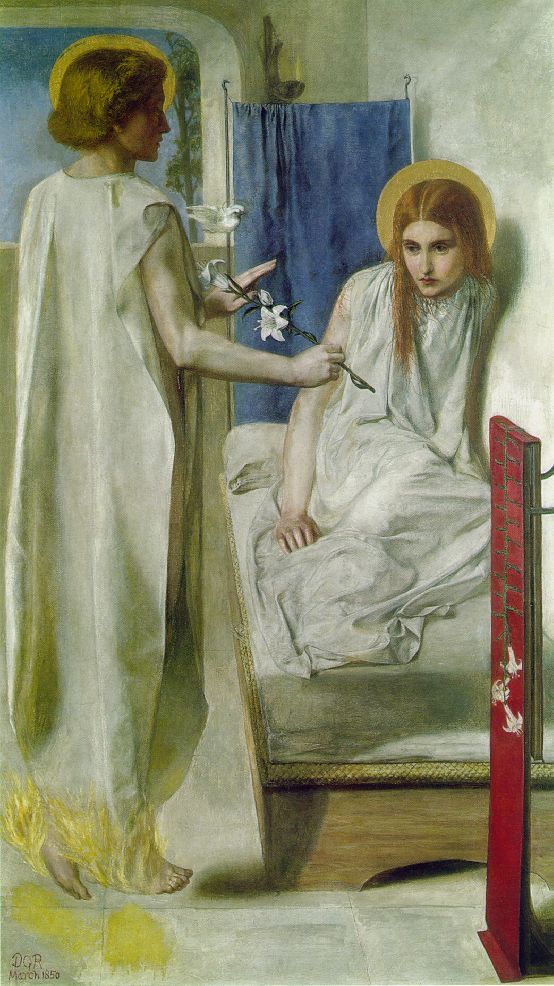

Rossetti, Ecce Ancilla Domini, 1849-50

Rossetti, Found, drawing

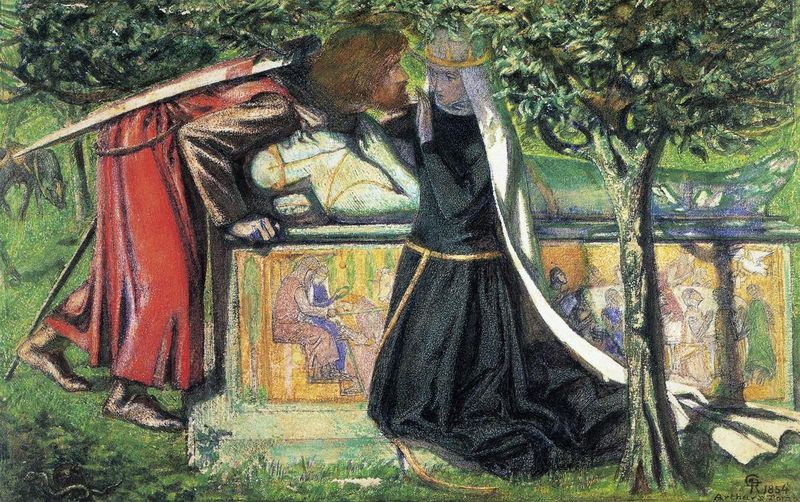

Rossetti also started with this sharp look in Ecce, Ancilla Domini! (Annunciation) and Found drawings. His sharpest ever was The Wedding of St. George, 1857 with narrow, geometrical figure types and an absence of the physical body. A body type that denies itself and reduces to a pattern. A decapitated dragon’s head. The whole composition is fragmented. Compare St. George and the Annunciation.

Rossetti, The Wedding of St George and Princess Sabra, 1857

Rossetti, Arthur’s Tomb, 1855

Incredibly strong attention to physical desire.

Nuptial Sleep

At length their long kiss severed, with sweet smart.

And as the last slow sudden drops are shed

From sparkling eaves when all the storm has fled,

So singly flagged the pulses of each heart.

Their bosoms sundered, with the opening start

Of married flowers to either side outspread

From the knit stem; yet still their mouths, burnt red,

Fawned on each other where they lay apart.

Sleep sank them lower than the tide of dreams,

And their dreams watched them sink, and slid away.

Slowly their souls swam up again, through gleams

Of watered light and dull drowned waifs of day;

Till from some wonder of new woods and streams

He woke, and wondered more: for there she lay.

Silent Noon

Your hands lie open in the long fresh grass,–

The finger-points look through like rosy blooms.

Your eyes smile peace. The pasture gleams and glooms

‘Neath billowing skies that scatter and amass.

All round our nest, far as the eye can pass,

Are golden kingcup -fields with silver edge

Where the cow-parsley skirts the hawthorn -hedge.

‘Tis visible silence, still as the hour-glass.

Deep in the sun-searched growths the dragon-fly

Hangs like a blue thread loosened from the sky.

So this wing’d hour is dropt to us from above.

Oh! clasp we to our hearts, for deathless dower,

This close-companioned inarticulate hour

When twofold silence was the song of love.

Rossetti

My Sisters Sleep

She fell asleep on Christmas Eve:

At length the long-ungranted shade

Of weary eyelids overweigh’d

The pain nought else might yet relieve.

Our mother, who had leaned all day

Over the bed from chime to chime,

Then raised herself for the first time,

And as she sat her down, did pray.

Her little work-table was spread

With work to finish. For the glare

Made by her candle, she had care

To work some distance from the bed.

Without, there was a cold moon up,

Of winter radiance sheer and thin;

The hollow halo it was in

Was like an icy crystal cup.

Through the small room, with subtle sound

Of flame, by vents the fireshine drove

And reddened. In its dim alcove

The mirror shed a clearness round.

I had been sitting up some nights,

And my tired mind felt weak and blank;

Like a sharp strengthening wine it drank

The stillness and the broken lights.

Twelve struck. That sound, by dwindling yea

Transcription Gap: two letters (type damage, text illegible)

Heard in each hour, crept off; and then

The ruffled silence spread again,

Like water that a pebble stirs.

Our mother rose from where she sat:

Her needles, as she laid them down,

Met lightly, and her silken gown

Settled: no other noise than that.

page: 171. Note: The second 1 in the pagination of page 171 is slightly raised.

Glory unto the Newly Born!

So, as said angels, she did say;

Because we were in Christmas Day,

Though it would still be long till morn.

Just then in the room over us

There was a pushing back of chairs,

As some who had sat unawares

So late, now heard the hour, and rose.

With anxious softly-stepping haste

Our mother went where Margaret lay,

Fearing the sounds o’erhead should they

Have broken her long watched-for rest!

She stooped an instant, calm, and turned;

But suddenly turned back again;

And all her features seemed in pain

With woe, and her eyes gazed and yearned.

For my part, I but hid my face,

And held my breath, and spoke no word:

There was none spoken; but I heard

The silence for a little space.

Our mother bowed herself and wept.

And both my arms fell, and I said,

God knows I knew that she was dead.

And there, all white, my sister slept.

Then kneeling, upon Christmas morn

A little after twelve o’clock

We said, ere the first quarter struck,

Christ’s blessing on the newly born!

Rossetti 1847

The Aesthetic Body

Rossetti, Fazios Mistress, 1863

I look at the crisp golden -threaded hair

Whereof to thrall my heart, Love twists a net

I look at the amorous beautiful mouth

I look at her white easy neck, so well

From shoulders and from bosom lifted out

Fazio degli Uberti C 14th

Bibliography

E. Prettejohn, The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites (Princeton 2000)

T. Barringer, Reading the Pre-Raphaelites (Yale 1998)

L Nochlin, The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity

(Walter Neurath Memorial Lectures) (Thames & Hudson 1995)

B. Prettejohn, Beauty and Art 1750-2000 (Oxford 2005) on Aestheticism

Chapter

[1] Bullen, The Pre-Raphaelite Body: Fear and Desire in

painting, poetry and criticism (Oxford 1998)

Pointon, M., Naked Authority: The Body in Western Painting 1830-1908

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990)

Pointon, M., and K. Adler, eds., The Body Imaged: The human form and visual

culture since the Renaissance (1993),(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1994)

P Barlow, Time Present And Time Past: The Art Of John Everett Millais

(London 2005)

C.Jacobi, William Holman Hunt, Painter, Painting, Paint (Manchester 2006)

Chapters 4 & 9

B. Prettejohn, Dante Gabriel Rossetti exhibition catalogue (Thames &

Hudson, 2003).

S Brown and Trodd, Representations of G F Watts: Art Making in Victorian

Culture (Ashgate 2004)

C. Cruise and V Osbourne, ed., Love Revealed: Simeon Solomon and the

Pre-Raphaelites (Merrell 2005)

Mort, F., Dangerous Sexualities: Medico-moral politics in England since 1830

(London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1987) also L. Nead & F. Mort ed. Sexual

Geographies (Lawrence and Wishart, 1999)

Gilman, S.L., Health and illness: Images of Difference (London: Reaktion

Books, 1995)

L. Jordanova, ‘The Representation of the Human Body: Art and Medicine in the

Works of Charles Bell’, Towards a Modern Art World, Studies in British Art 1, ed. B. Allen,

London: (Yale 1995), pp 79-94

J van Wyhe, Phrenology and the Origins of Victorian Scientific Naturalism

(Ashgate 2004)

M Cowling, The Artist as Anthropologist: The Representation of Type and

Character in Victorian Art

(Cambridge University Press, 1989), also M Cowling, Victorian Figurative

Painting: The Pre-Raphaelites (2003)

J Eli Adams, Dandies and Desert Saints: Styles of Victorian Masculinity

(London: Cornell University Press, 1995)

Sussman. H.L., Victorian Masculinities (Cambridge, Cambridge University

Press, 1995)

Codell, J.F., ‘The artist colonised: Holman Hunt’s ‘bio-history’, masculinity,

nationalism and the English school’, Re-framing the Pre-Raphaelites:

historical and theoretical essays, ed. E. Harding, (Scolar Press, 1996), pp

211-29

T. Barringer Men at Work Art and Labour in Victorian Britain (Yale

University Press 2005)

Kestner, J.A., Masculinities in Victorian Painting (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1995)

Nead, N., Myths of Sexuality: Representations of Women in Victorian Britain

(Blackwell 1888)

L Pearce Woman, Image, Text: Readings in Pre-Raphaelite Art (Prentice

Hall 1991)

Smith, A., The Victorian Nude, (Manchester: Manchester University Press,

1996)

R. Leppert The Sight of Sound: Music, Representation and the History of the

Body (California 1993)

Bown, N., C. Burdett and P. Thurschwell, eds., The Victorian Supernatural

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004)

E. Prettejohn ed., After the Pre-Raphaelites: Art and Aestheticism in

Victorian England (Manchester University Press and Rutgers University Press,

1999)

M. Pointon, ed., Pre-Raphaelites Re-viewed (Manchester, 1989)

E. Harding, ed., Re-framing the Pre-Raphaelites: Historical & Theoretical

Essays (Hampshire, 1996)

(These are notes of a course given at Birkbeck College by Carol Jacobi in 2006/2007)