Painting consists in putting coloured pigments on a flat surface. The pattern created can be interpreted in many ways. There may be no clear relationship between the pattern and the world and we call this an abstract painting. The patterns may be interpreted as objects in the world or in an imaginary and we call this representational or figurative.

One distinction that can be made if the painting is figurative is between narrative and iconic paintings. An iconic painting is representative (it represents something) but is timeless and a narrative painting is a moment in time (a snapshot) or a series of moments. The moment depicted by a narrative painting is typically a carefully chosen point between what has been and what might be. The die is cast and we can foresee the consequences. One skill required of a narrative painter is to be able to select a moment in time that best expresses the feeling the artist wishes to convey.

Another way to look at paintings is in terms of the five genres, first formulated by André Félibien (the historiographer, architect and theoretician of French classicism) in 1667. This hierarchy of genres considered history painting to be “the great genre”. History paintings include paintings with religious, mythological or historical subjects that convey a moral message. It is difficult today to appreciate why history painting was the highest genre. It was not just representing a scene in the bible or from mythology but capturing what is best and most noble in human beings.

The hierarchy of genres was not some arbitrary system but it reflected the social importance of conveying a serious, uplifting and noble moral message. The hierarchy reflects the ability of each type of painting to capture a moral message. Félibien wrote, “He who produces perfect landscapes is above another who only produces fruit, flowers or seashells. He who paints living animals is more estimable than those who only represent dead things without movement, and as man is the most perfect work of God on the earth, it is also certain that he who becomes an imitator of God in representing human figures, is much more excellent than all the others.”

Following his precepts, after history painting came portraits and scenes of everyday life (called “scénes de genre”). Then came landscapes and finally still-lifes or what he called “fruit, flowers or seashells”. Notice that the key to understanding the order is the involvement of human beings because we bring meaning and morality. The hierarchy of genres had a corresponding hierarchy of formats and materials: large format oil paintings for history paintings, small format for still-lifes. Still-life are often drawings, which included watercolour painting, pastels and other drawing materials.

This hierarchy, maintained by the Academy, was progressively called into question during the nineteenth century. In his report on the 1846 Salon, Théophile Gautier already saw that, “religious subjects are few; there are significantly less battles; what is called history painting will disappear…The glorification of man and of the beauties of nature, this seems to be the aim of art in the future”. Note that the glorification of man was the aim of history painting. What Gautier was saying was that the method used, with its classical figures and scenes from mythology had become outdated and new approaches had to be found to represent the modern world.

The other way to look at a painting is through a sequence of analytical questions:

- State the facts (when known)—material, artist, date, subject, patron, period produced, period depicted, relation to other images by the same artist and the same image by other artists.

- Scan the picture unconsciously and then consciously and record where you looked and what you noticed. It is sometimes useful to described the work in words as this forces precision and care in looking.

- Examine the facture, that is, the surface finish of the work, and the craftsmanship.

- Analyze the use of line and colour. One important distinction in the Italian Renaissance was between ‘disegno’ or design as signified by the precision of the drawing and ‘colorito’ or colouring which gave precedence to the mastery of tones and hues. This distinction was important as it reflected the relative importance of intellectual analysis or reason as embodied in the precision of the drawing and feeling and human emotion as embodied in the colour.

A more detailed formal analysis that can be used for painting is based on the acronym MASTERCLASS CHAP.

Jacques-Louis David, The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons, 1789

This is a typical history painting depicting a pivotal moment. Brutus is shown on the left in shadow and his sons’ bodies are being brought in the door behind him. His sons had revolted against his tyranny and Brutus, in his capacity as a judge, had sentenced them to death.

This a serious painting that suggests that principles must be put above personal feelings. This was very relevant at the time as it was painted the year of the French Revolution. The painting had a powerful effect and helped bring in a new fashion for elegance and simplicity, corsets were banished and hair was worn loose.

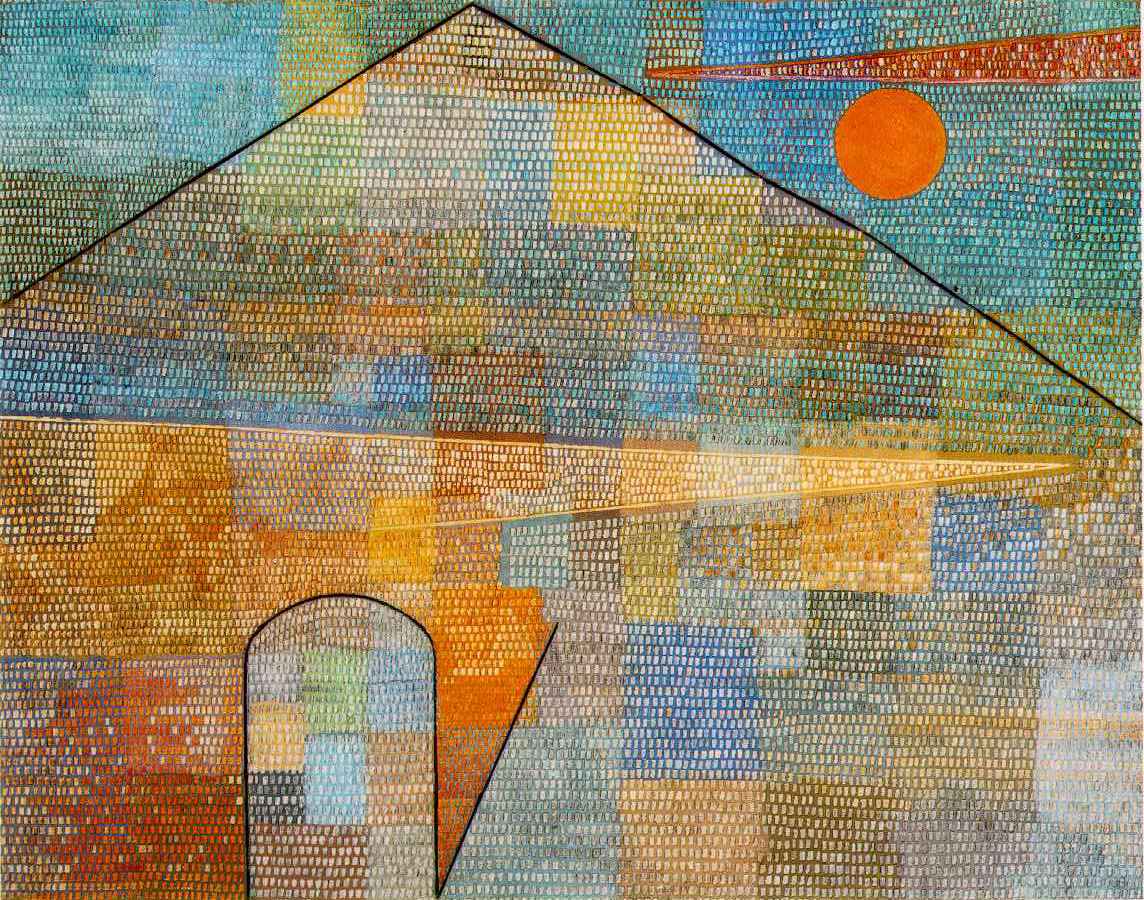

Paul Klee, Ad Parnassum, 1932

There is no precise narrative here but it is representational, we see a house beneath a deep red burning sun. The blues, oranges and yellows invoke feelings of hot summer days. The drawing is sketchy, there is what could be a door into a house although the line at the top could be a mountain or a gable roof.

John Everett Millais, A Huguenot, on St. Bartholomew’s Day Refusing to Shield Himself from Danger by Wearing the Roman Catholic Badge, 1852

A strong narrative painting the refers to a terrible event. On St. Bartholomew’s Day, August 24, 1572, 100,000 Protestants (Huguenots) were killed in France. The Roman Catholics wore ribbons to indicate their faith and to avoid be massacred. We know that by refusing to wear the ribbon he is facing certain death. His female companion is trying to tie the ribbon round his arm as he pulls it away.

This section indicates the wide range possibilities inherent in the process of painting and so the enormous flexibility it offers the artist..