Laurence Shafe, 22 February 2004

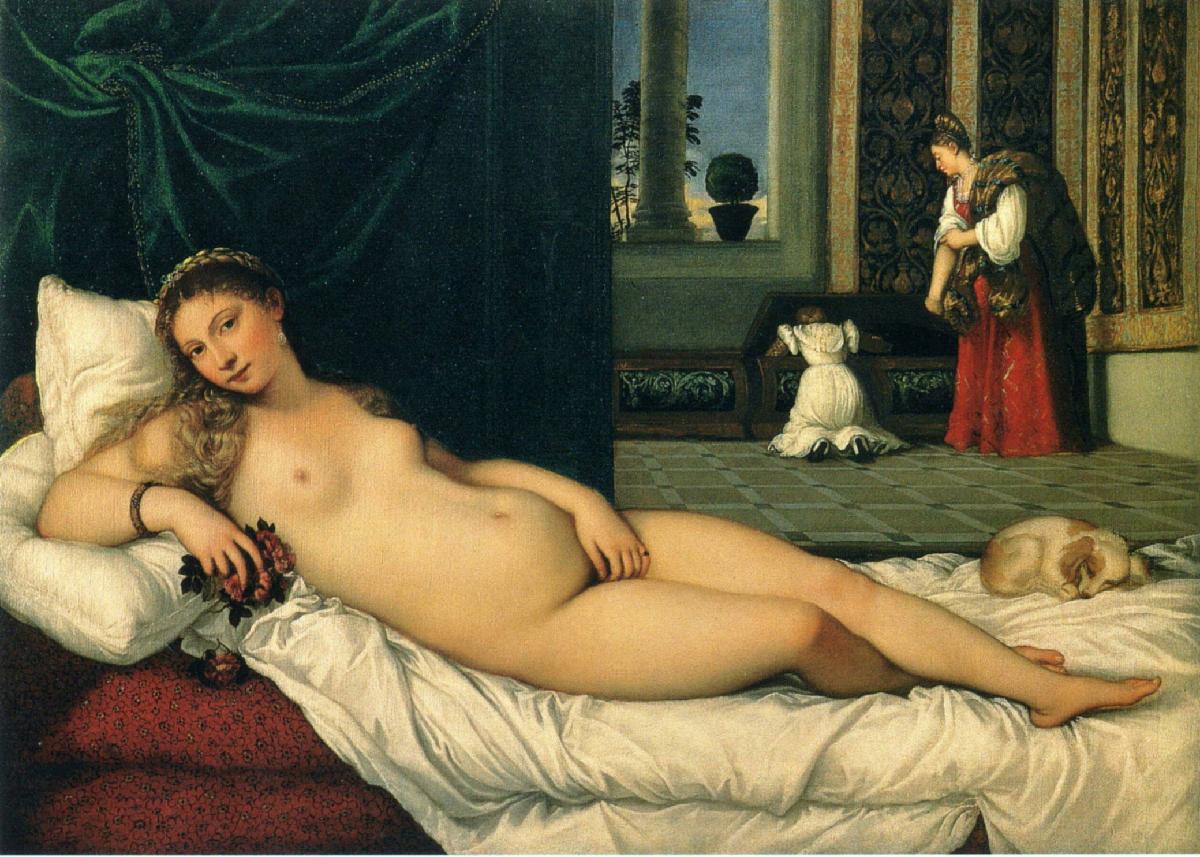

I will start by considering one painting, Titian’s Venus of Urbino (Figure 1), as an exemplar of the sixteenth century female nude. It raises many questions such when was it commissioned? Was it a marriage painting? Or is it, as some have claimed, a ‘pin-up’? The answers raise further issues about sixteenth century Italian society and the role of the nude.[1] I look at these social and religious issues, the categories of nude painting[2] and the use of symbolism and argue that the nude cannot be seen simplistically as either a ‘pin-up’ or as purely contemplative work.

The Venus of Urbino was painted for Guidobaldo, duke of Camerino, although we do not know if it was commissioned.[3] The title of the painting raises the vexed question of why it was painted and what it represents[4]. It is unlikely that Guidobaldo commissioned the painting as he had already been married for four years[5] and if he had commissioned it he would have been less concerned about losing it to another buyer.

My view is that it is a marriage painting of an idealized woman (a ‘Venus’[6]) that Titian painted as a ‘set piece’ for his studio. By a set piece I mean a painting that he decided to paint himself[7] to demonstrate his skill to potential customers and perhaps simply because it pleased him. Titian was a shrewd business person and if he found a buyer he would no doubt sell any such demonstration piece.

Figure 1: Titian’s Venus of Urbino, 1538, Oil on canvas, 119 x 165 cm, Uffizi, FlorenceIn the painting Titian has cleverly linked the open cassone (marriage chest) in the background (see detail Figure 2) to the spatially disjoint[8] reclining woman to create a picture within a picture; the reclining nude representing the idealized nude often found inside the lid of marriage chests.

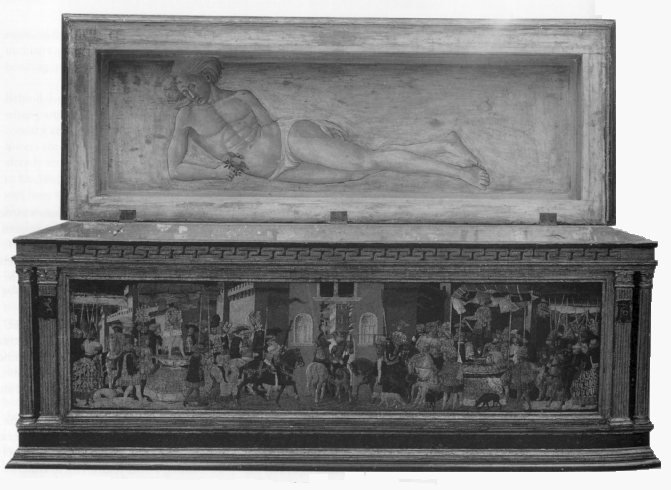

Marriage chests[9] (cassoni) were an important symbol of marriage in Renaissance Italy. They were carried through the streets during the marriage ceremony and were frequently elaborately and expensively carved and decorated to demonstrate status. The outside of the chest and inside of the lid were often painted and the inside of the lid sometimes had a painting of a naked person. Renaissance people believed in the magic of images, that they could hear, speak and see,[10] and it was thought that gazing at the image of a beautiful person before sexual intercourse would lead to a beautiful child. The naked person painted inside the lid could be male or female (or both); Figure 3 shows an example of a naked man which was probably one of a pair with the other showing a naked woman.

Figure 2: Titian, Venus of Urbino (detail)Titian has taken the convention of the nude hidden within the marriage chest lid and combined it with the depiction of Venus taken from Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (Figure 4). The Giorgione painting had been completed by Titian about twenty years previously and is more clearly a Venus because of the Cupid on the right hand side (overpainted in 1843 so now only visible by X-ray photography).

Figure 3: Florentine School, a cassone, c.1460, 2.05m long, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Copenhagen The woman’s glance, the colorito[11], the role of the viewer, the position of the hand and its significance, the symbolism of the dog and the objects in the room, the ownership of the dog, the fact that it is sleeping, the two internal disjoint spaces, the ‘incorrect’ perspective, the techniques used to lead the eye and the activity of the servants all combine to create an image that arouses us in many ways. The painting is a perfect example of what I believe is the artist creating an intentionally ambiguous, or what could be called balanced, image. The ambiguity or balance is between the erotic and the intellectual, or to put it more crudely between pornography and ‘high art’. My view may seem obvious but it is not the view of many famous commentators, such as Kenneth Clark.[12]

To take another extreme view, Samuel Langhorne Clemens (better known as Mark Twain) described the Venus of Urbino as “the foulest, the vilest, the obscenest picture the world possesses.”[13] Recently the painting has been described simply as an excuse for a ‘pin-up’.[14] These extreme simplistic, sexual interpretations ignore the precedents, symbolism and the social context of sixteenth century Italy. Even today the nude is not simply a pin-up; for example, it still retains an association with purity and innocence as demonstrated by its use on memorials.

Figure 4: Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (completed by Titian), c. 1508-1510, Oil on canvas, 108 x 175 cm, Gemaeldegallerie Alte Meister, Dresden

In order to create a more balanced view we must look at the social context and symbolism of the sixteenth century. It was a time of growing wealth not just for the top level of society but for merchants, professionals and officials. One important area in which this wealth was spent was the arts through a system of patronage. Patronage was very important to the patron and a network of patronage relationships was considered essential to progress a career and improve one’s social standing.

It was a rigid, rule-bound society in which the wealth, status, family, marriage and the church were extremely important. Neither women nor men were free to pursue their own ambitions and the role of women was limited to marriage or entering a convent[15].

Women clearly had few choices in the sixteenth century like many other social groups. Prior to marriage daughters were often kept locked away and if they went outside many wore veils. Marriage was often arranged and it involved a substantial financial dowry and the joining of two families.[16] After marriage a woman’s role was to obey her husband, have male children and manage the household. However, we should avoid a too simplistic view as the way that legal notices at the time were worded suggests that they were often ignored by women.[17]

The other great social force was religion. The depiction of the erotic nude was forbidden and it is interesting that the inquisition defends Michelangelo’s depiction of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, St. John and St. Peter in the nude with the words “in those figures there is nothing that is not spiritual.”[18] This indicates that it was not nudity per se that was objected to by the church but the intent, and no doubt their view of the intent was influenced by the fame and status of the artist. The church had to refuse to see any ambiguity in the image as otherwise it would admit the possibility that the images included an element of the erotic. Their analysis was clearly one-sided, like that of Lord Longford in the 1970s. It may be that to exert power, be it religious control or censorship, one must always maintain a one-sided view.

In earlier centuries the principal role for the artist in Italy was to create religious works. The nude was rarely seen and, if shown, was stylized with a thin, angular body and breasts and stomach that looked as if they were stuck on. This ‘Gothic nude’ started to be replaced by the Renaissance nude at the end of the fifteenth century as illustrated by Botticelli’s La Primavera[19] (1477-78). This work, almost on its own, created a category of painting and a new way of representing idealized female beauty.[20] The figures in La Primavera are clothed but in 1485-86 Botticelli painted the full length female nude of Venus anadyomene. La Primavera is a profoundly original work and was painted just before Girolamo Savonarola’s[21] bonfire of the vanities in 1496 in Florence.[22] Savonarola believed all images of naked women and men could corrupt those who saw them and many paintings of this type were burnt. Thankfully La Primavera survived but the religious atmosphere probably held back the development of the nude in Florence.

In 1500 Piero di Cosimo painted a recumbent nude[23] and in 1515 the aging Bellini painted Young Woman Holding a Mirror (Oil on canvas, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria) significant for being a naked young woman apparently without mythological associations.

Perhaps the most significant painter of the full length nude was Giorgio da Castelfranco Giorgione who painted two such nudes[24] in the early sixteenth century. Venus Asleep can be seen as the precursor to Titian’s Venus of Urbino and both were exerting an influence on artists over three hundred years later.[25]

The other great painter of the female nude in the early sixteenth century was Raphael (1483-1520) who painted many nudes.[26] Raphael made the point in a letter to Baldassarre Castiglione that “in order to paint one beautiful woman I’d have to see several beautiful women but since there is a shortage of beautiful women, I make use of a certain idea which comes into my mind.”[27] This indicates the Raphael was not painting a particular woman but an idealized woman made up from parts of women he had seen and his imagination.

Female nudes were also shown in sculptures but this was limited to mythological scenes that involved naked women or naked goddesses, such as Giovanni da Bologna (c.1524-1608) Rape of the Sabines (1581-83) or Michelangelo’s Medici Chapel, San Lorenzo, Florence (1519-34). The relatively small number of female nudes represented in sculptures compared to paintings may be because they tended to be more publicly on view.[28]

During the sixteenth century ecclesiastical attacks on erotic images grew in intensity. In the mid-sixteenth century the Council of Trent (1545-1563) gave rise to the Counter-Reformation. The twenty fifth and last session allowed ” the legitimate use of images” but warns that “all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust”[29] This left the artist and patron treading a fine line between spiritual beauty and beauty “exciting to lust” with any mistakes by the artist investigated by the inquisition.

Despite the dangers of the inquisition the female nude blossomed as an art form in sixteenth century Italy. Other well known painters of the nude were, in order of date of birth, Michelangelo (1475-1564), Il Sodoma (1477-1549), Il Vecchio (1480-1528), Correggio (1489-1534), Dosso Dossi (1490-1542), Pontormo (1494-1557), Giampietrino (1500-1540), Bassano (c.1515-1592), Schiavone (c.1515-1563), Tintoretto (1518-94), Veronese (1528-1588), Allori (1535-1607), and Zucchi (c.1540-1596).

Also by the sixteenth century the role of the artist in Italian society had become respected and some artists, for example, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian, became important people in their own right and were increasingly able to paint without a commission and therefore choose their own subjects.

One category of painting that appealed to the wealthy mostly male patron was the female nude. This was for the obvious erotic and aesthetic reasons but also because any work of art that had humanist or classical connections was thought to be morally uplifting and a talking point for the patrons’ associates and finally because in certain situations it was thought to have a practical benefit, such as creating beautiful children.

The social, political, and religious background therefore allowed the depiction of the female nude in prescribed circumstances and I would next like to consider those circumstances by looking at four categories – religious works, mythological works, portraits and furniture panels.[30] The invention of the printing press also created a new category of cheap erotic print but it is not known how widely these circulated and it will not be considered further.[31]

Religious works depicting the female nude can be divided into those that depict the nude almost necessarily, for example Eve[32] and the Last Judgment[33] and those that appear to have been selected in order to show the female nude, such as Susanna[34] and Bathsheba[35].

It is in the classically inspired mythological works that the female nude is most often depicted in sixteenth century Italy. Many suitable subjects were found in mythology including Venus, the three Graces, the judgment of Paris, Danaë, Flora, Leda, Europa, Diana, Lucretia and Io. These images reinforced the interest in the classical and in humanism and their symbolism supported learned debate with attractive images.[36]

The third category is the portrait. This developed from the simple profile in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries to the three quarter view and then to the representation of the individual personality in the sixteenth century. One type of ‘portrait’ was the naked or partly naked mythological portrait, for example, of Flora[37], goddess of spring. A respectable woman would never be shown naked or partly naked so it is likely that artists used courtesans as models and supporting this conjecture we do find the same face appearing in different works. It is likely, for example, that the Venus of Urbino was modelled by a courtesan as the same woman appeared two years previously in Titian’s La Bella, but this does not detract from the argument that the painting represents Venus.

The final category is the use of painted panels to decorate furniture. The example of marriage chest decoration has already been mentioned. These paintings often made a moral point or were in some way reinforcing the beliefs of the society.

Artists in sixteenth century Italy began to find ways to overlap these categories. As has been pointed out the Venus of Urbino exploited and developed the idea of the marriage chest painting and portraits were painted of mythological characters, for example, Flora, goddess of spring, was painted in portrait form but of a mythical person.

Having discussed the categories we need to look at possible interpretations. Any discussion of the depiction of the female nude in sixteenth-century Italian art raises issues of interpretation and gender that go to the heart of many current art historical disagreements. There are unfortunately few primary sources describing such paintings.

The two most significant primary sources that describe the context of sixteenth century painting and its interpretation at the time are Giorgio Vasari’s “Lives of the Artists” and Lodovico Dolce’s “Aretino”.

Regarding the Venus of Urbino, Vasari when describing this period of Titian’s life says, “In the wardrobe of the same duke a young recumbent Venus with flowers and light draperies about her (a very beautiful and well-finished picture).”[38] This categorically identifies the painting as a Venus in Vasari’s eyes and therefore the eyes of a knowledgeable sixteenth century artist.

Dolce, commenting on the painting[39] makes it clear that the painting has an explicit erotic appeal, “there is no man who does not feel a warming, a softening, a stirring of the blood in his veins. It is a real marvel; that if a marble statue could by the stimuli of its beauty so penetrate to the marrow of a young man, that he stained himself, then, what must she do who is of flesh, who is beauty personified and appears to be breathing?” The marble statue he is referring to is probably the Cnidian Venus of Praxiteles (also known as the Modest Venus or Venus Pudica).

It is also worth noting that despite all the comments made about the erotic nature of the Venus of Urbino one of the Pope’s ambassadors, the papal nuncio Giovanni della Casa described the Venus as a ‘Theatine nun’[40] compared to Titian’s Farnese Danaë[41] of 1545.[42]

Given these views it is interesting to look at two current analyses of the Giorgione Sleeping Venus painting. Paoletti in 2001 says: “Her left hand seems not to be modestly hiding her genitals but apparently pleasuring them”[43] and goes on to discuss the perceived benefit of female masturbation at the time. Only thirty years previously, in 1971, Freedberg could analyze the painting without mentioning sex or eroticism: “All the sensuality has been distilled off from this sensuous presence”[44]

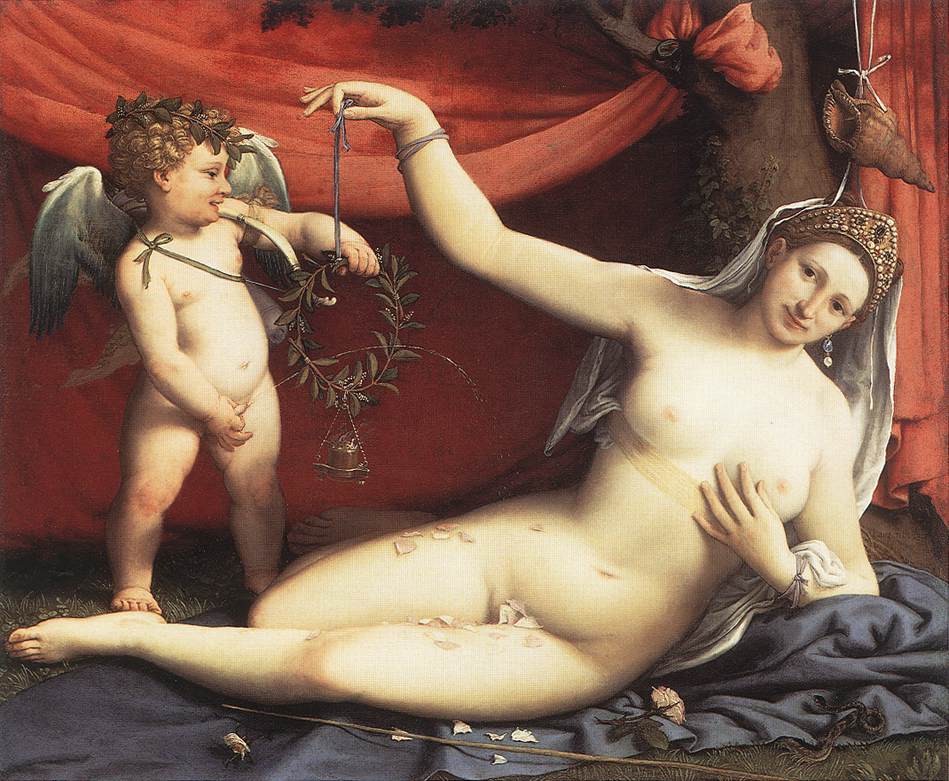

Figure 5: Lorenzo Lotto, Venus and Cupid, 1540, Oil on canvas, 92.4 x 11.4 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It is easy to dismiss Freedberg’s view as outdated but it was a valid view comparatively recently, bearing in mind the time that has elapsed since Vasari’s and Dolce’s views. The diametrically opposed views of modern commentators highlight the difficulty faced when trying to interpret the significance and symbolism of the art of a past period.

The difficulty of applying today’s standards to sixteenth century painting can also be illustrated by looking at some examples.

In the fourteenth century the Sienese had destroyed an antique statue of Venus as they believed it had brought bad luck. Johnson argues that statues of women had all been “demonized, removed or rendered impotent in central Florence by the end of the sixteenth century”.[45] This indicates that Italian men had mixed feelings regarding images of women and shows the power which images were thought to possess compared to today.

Figure 6: Bronzino’s An Allegory with Venus and Cupid, 1540-50, National Gallery, London

Figure 6: Bronzino’s An Allegory with Venus and Cupid, 1540-50, National Gallery, London

Lotto’s Venus and Cupid (Figure 5) is full of symbolism, much of it lost to us today. It shows Cupid urinating (or some suggest ejaculating) through a myrtle wreath onto a naked Venus. It is difficult to interpret the painting as a “pin-up”; in fact it is difficult to apply any current category. We know that the painting was a marriage painting symbolizing good luck.

A second painting that is full of symbolic meaning is by Bronzino (Figure 6). A lot of the symbolism is now lost but it has been suggested that the picture was a moral tale of the dangers of illicit sex. For example, the figure in the left background has been described as suffering from advanced syphilis but it is mostly speculation and we are not able to interpret the painting fully today.

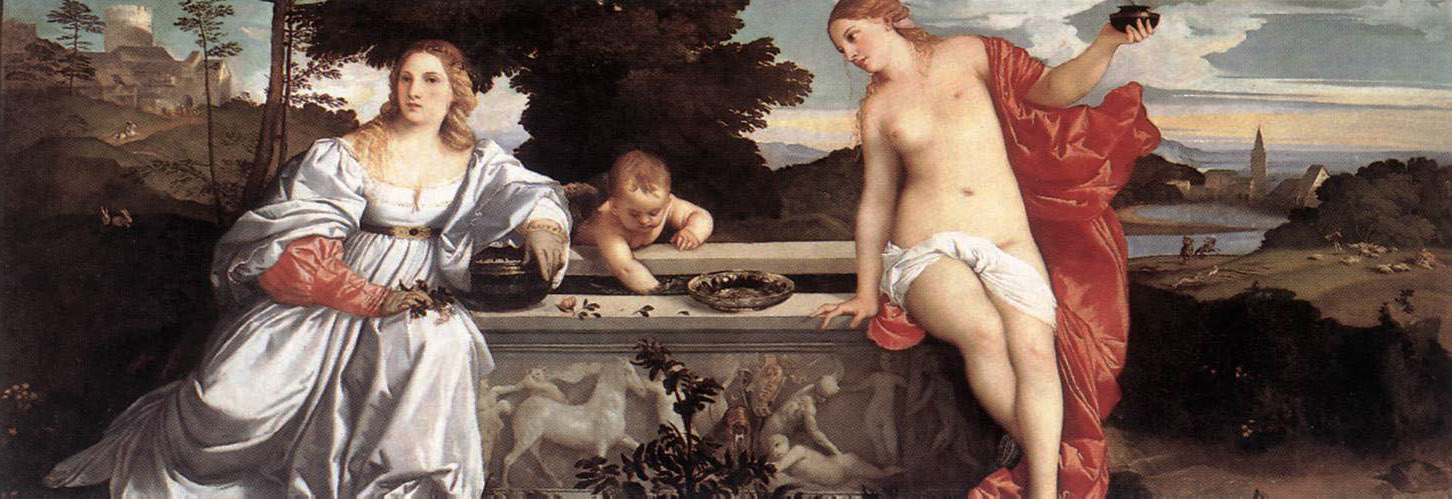

Finally, even an apparently straightforward painting such as Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love (Figure 7) is not what it appears. It is a marriage picture (commissioned for the marriage of the Paduan noblewoman Laura Bagarotto to Nicolo Aurelio) and the naked woman on the right represents Sacred Love, the clothed woman on the left Profane Love. However, the woman shown is not the bride as it would have been unthinkable to show her nude and the same woman appears as Flora in 1515. Titian was showing two sides to the bride’s character, her chastity and her sexuality which combined will result in a fecund marriage as symbolized by among other images, the large rabbits in the landscape.

Figure 7: Titian, Sacred and Profane Love, 1514, Oil on canvas, 118 x 279 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy

As pointed out by Goffen it is unthinkable that the Lotto image or even the Sacred and Profane Love would be used to publicize a marriage today.[46]

I have explained how paintings of the nude in the sixteenth century must be interpreted within the social norms of the time and I have argued that they were created with, and continue to maintain, an inherent ambiguity. The ambiguity was between their appeal to the intellect through their dense symbolism, classical references and idealized form and their appeal to the senses, specifically as erotic images.

I have also explained the categories that were recognized by the Renaissance viewer and I have argued that the development of the nude during the sixteenth century took place partly through redefining the boundaries of each category and by combining categories.

More importantly, I have tried to show that simplistic interpretations of the sixteenth century female nude, such as “it’s a pin-up” or alternatively “it’s purely an object of contemplation” ignore the rich, multi-layered, and above all ambiguous reality.

Bibliography

Alberti, L. B. On Painting (London, Penguin Classics, 1991, based on C. Grayson’s translation of the work first published in Latin in 1435)

Berger, J. Ways of Seeing (London, Penguin, 1972)

Chadwick, W. Women, Art and Society (London, Thames & Hudson, 2002, first published 1990)

Clark, K. The Nude (London, John Murray, 1956)

Fiore, K. H. Guide to the Borghese Gallery (Italy, Gebart s.r.l., 1997)

Freedberg, S. J. Painting in Italy 1500-1600 (Middlesex, Penguin Books, Second Edition 1983)

Gerlini, E. Villa Farnesina Alla Lungara (Rome, Instituto Poligrafico E Zecca Dello Stato, 2000)

Goffen, R. Titian’s Venus of Urbino (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1997)

Gombrich, E.H. Art & Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (London, Phaidon, 2002, first published 1960)

Jaffe, D. Titian (London, Yale University Press, 2003)

Johnson, G. A., Matthews Grieco, S. F. Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1997)

Le Goff, R. Venetian Portraiture 1475-1575, Mistresses and Courtesans, A Discussion of the Erotic Appeal of the So-Called Belle Donne Portraits Concentrating on the Works of Palma Vecchio and Titian (Presented at the Courtauld Institute London, November 1994)

Levey, M. High Renaissance (London, Penguin Books, 1991, first published 1975)

Murray, P. and L. The Art of the Renaissance (London, Thames & Hudson, 1963)

Nead, L. The Female Nude: Pornography, Art, and Sexuality, Signs (1990: Winter)

Paoletti, J.T. and Radke, G. M. Art in Renaissance Italy (London, Laurence King, 2001)

Shearman, J. Mannerism (London, Penguin Books, 1967)

Tinagli, P. Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender Representation and Identity (Manchester and New York, Manchester University Press, 1997)

Vasari Lives of the Artists (Middlesex, Penguin Books, 1977, translated and first published in 1965 by G. Bull)

Welch, E. Art in Renaissance Italy (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1997)

Endnotes

[1] In fact they raise much broader questions. As Lynda Nead points out in “The Female Nude: Pornography, Art, and Sexuality,” Signs (1990: Winter): “Within the history of art, the female nude is not simply one subject among others, one form among many, it is the subject, the form.” The term ‘nude’ also raises questions about the distinction between the naked and the nude which is not discussed here, see Clark, The Nude (1956) and Berger, Ways of Seeing (1972).

[2] I focus primarily on painting although the female nude in sculpture is mentioned later.

[3] Jaffe, D. Titian (London, Yale University Press, 2003), page 19. Guidobaldo visited Titian’s studio in January 1538 and had his portrait painted. This was unremarkable as, by then, Titian was about 50 years old (although his date of birth is not known with certainty) and famous internationally. It is thought the duke saw a painting of a naked woman (‘donna nuda’ or naked woman is the phrase used by Guidobaldo in his letter to Titian of March 9, 1538) in Titian’s studio and on 1 May he wrote to Titian asking him not to sell it to anyone else while he tried to raise funds to buy it. His mother agreed to pay for both paintings and the painting of the naked women was delivered later that year. Guidobaldo became Duke of Urbino in October the same year and the painting is now called the Venus of Urbino.

[4] Titian called this type of painting a poesie (literally poem) to indicate they were not to be taken as realistic depictions, for example, of a naked courtesan lying on a bed. This convention was maintained by artists painting the female nude by means of idealization and symbolism until broken in 1863 by Manet with Olympia.

[5] He was married to the ten year old Giulia Varano of Camerino in 1534. This was not unusual and the convention was that a husband would not engage in sexual intercourse until the menarche, which was typically at the age of fourteen. It has therefore been suggested that it was purchased as a belated marriage painting or commissioned earlier in anticipation of the event.

[6] There is no precise definition of what constitutes a ‘Venus’. The convention was often to paint a particular naked women but not one who was part of wealthy society, such as a courtesan, and modify the image based on accepted conventions of idealization used to represent feminine beauty and then label the image using a known symbol, such as Cupid. In this case Titian did not include a Cupid but indirectly referred to one by creating an image based on Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus. Venus was shown naked to symbolize her purity and as a reference back to classical sculptures.

[7] In the fifteenth century most paintings were commissioned and therefore the subject matter was usually specified by the patron. By the sixteenth century some artists, such as Titian, could paint, between commissions, pictures of their choosing and hope to sell them later.

[8] The floor tiles in the background are at a different level from the base of a normal height Renaissance bed and the green curtain behind the nude isolates her from the background. This has been pointed out by a number of writers; see Arasse, D. “The Archetype of a Glance,” in Goffen, R. (Ed) Titian’s Venus of Urbino, pages 91-107.

[9] They typically came in pairs.

[10] Goffen, R. “Sex, Space, and Social History,” in Goffen, R. Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1997), page 65.

[11] In Venice colorito, the use and application of colour, was seen as fundamental to the creation of a work of art.

[12] In Kenneth Clark’s testimony to the Lord Longford committee on pornography he said “To my mind art exists in the realm of contemplation, and is bound by some sort of imaginative transposition. The moment art becomes an incentive to action it loses its true character.” See Nead, L. The Female Nude: Pornography, Art, and Sexuality in Signs (1990: Winter), pages 323-335.

[13] Rosand, D. So-and-So Reclining on Her Couch in Goffen, R. Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1997), page 38, quotes from Mark Twain’s A Tramp Abroad (1880). It is possible he was trying to make a point about freedom of speech as he continues by explaining that he would not be allowed to describe the position of the hand even though he is allowed to view it as ‘Art’ but this motive does not diminish his extreme views.

[14] Some critics, such as Hope, Ost and Zapperi have described the Venus of Urbino as a pin-up, soft core pornography and simply a nude woman lying on a bed; see Goffen (1997), p. 17. Also, see p. 68 for the more extreme view of Orest Ranum that the painting is “pornography for the elite”.

[15] The full picture of society at the time is more complex. For example, in cities women would typically marry when they were fourteen but men not until they were over twenty five. This meant that there were many single young men, giving rise to violence and funding prostitution. It also meant that those women that survived continual childbirth would often inherit their husband’s wealth.

[16] The importance of the family is indicated by the fact that if one family member was dishonoured or attacked or committed a crime then it was as if every member of the family had been treated or acted in that way.

[17] Welch, E. Art in Renaissance Italy (1997), page 279 describes how sumptuary laws should not be read as legislation that worked but as evidence for the kind of activities that caused anxiety.

[18] See Paoletti, J. T. Art in Renaissance Italy (2001), page 454 for part of the transcript of the trial. Note that Veronese says “all represented in the nude even the Virgin Mary” but he was wrong as she is fully clothed. The Inquisition did not pick up this mistake in their reply.

[19] La Primavera, (“Allegory of Spring”), c.1482; Tempera on wood, 203 x 314 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; painted for the villa of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici at Castello. He later painted The Birth of Venus, c.1485-86; also painted for the villa of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici; Tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm; also now in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence and Venus and Mars, c.1485, Egg tempera and oil on poplar, 69 x 173.5 cm, National Gallery, London.

[20] This is not to imply that there is such a thing as a universal female beauty, all beauty is a social construct.

[21] Preached in Florence from 1489 until excommunicated in 1497 and burned as a heretic in 1498.

[22] Tinagli, P. Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender Representation and Identity (1997), page 122.

[23] More accurately a dead female body, The Death of Procris, c. 1500, Oil on panel, 65 x 183 cm, National Gallery, London.

[24] Pastoral Scene (Fete Champêtre), completed by Titian, 1508-9, Oil on canvas, 105 x 136 cm, Musee du Louvre, Paris and Venus Asleep, c. 1508-1510, Oil on canvas, 108 x 175 cm, Gemaeldegallerie Alte Meister, Dresden.

[25] For example, Manet’s Dejeuner sur l’herbe, 1863, oil on canvas, 208 x 264 cm, Musee d’Orsay and his Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 130.5 x 190 cm, Musee d’Orsay, Paris.

[26] The Three Graces, 1504-05; Loggia di Psiche, 1509-11; Portrait of a Nude Woman (the ‘Fornarina’), c. 1518, oil on panel, 85 x 60 cm, Galleria Nazionale, Rome; The Triumph of Galatea, 1509-10, c. 1512-14, fresco, 295 x 225 cm, Villa Farnesina, Rome.

[27] Tinagli (1997), page 2.

[28] The issue of public and private representations of the female nude is an important one. It is known that paintings of female nudes were often covered with curtains even in private houses and some villa’s had special private areas containing classical sculptures of Venus.

[29] The Council of Trent, The Twenty-Fifth Session, The canons and decrees of the sacred and oecumenical Council of Trent, Ed. and trans. Waterworth, J. (London: Dolman, 1848), pages 232-89.

[30] Tinagli (1997) identifies four categories in which Renaissance women (not just nudes) are depicted painted furniture, portraiture, religious images and the nude.

[31] There was also a new category of prurient story created almost single handedly by Pietro Aretino, one of which was illustrated by engravings of sixteen sexual positions by Marcantonio Raimondi.

[32] For example, early works include Giovanni Pisano’s pulpit in Pisa 1302-10 and Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Eve on the eastern door of the Baptistery in Florence, 1425.

[33] For example, early works include Giotto’s Universal Judgement, c.1303 and Masaccio’s Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise, 1427.

[34] For example, Lorenzo Lotto’s Susanna and the Elders, 1517, Oil on wood, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence and Tintoretto’s The Bathing Susanna, 1560-62, Oil on canvas, 146.6 x 193.6 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

[35] For example, Jacopo Zucchi, The Toilet of Bathsheba, after 1573, Oil on panel, 120 x 144 cm, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome.

[36] The word ‘attractive’ implies ‘to men’ and I am assuming that most patronage was by men but this was not entirely the case, for example, Marchesa Isabella d’Este (1473-1539) and Catherine de Medici (1519-1589) were well known patrons of the arts.

[37] For example, Titian, Flora, c.1515-1520, Oil on canvas, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

[38] Vasari, Lives of the Artists (1965 edition), page 453.

[39] Ginzburg, C. “Titian, Ovid & Sixteenth-Century Codes,” in Goffen, R. (Ed) Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1997), page 28.

[40] It is puzzling that the order of Theatine Sisters in Naples was not established by Venerable Ursula Benincasa until 1581, which appears to post date the quotation.

[41] Part of the Farnese collection and now in the Gallerie di Capodimonte in Naples.

[42] Arasse, D. “The Archetype of a Glance,” Goffen, R. (Ed) Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1997), page 103.

[43] Paoletti (2001), page 385.

[44] Freedberg, S.J. Painting in Italy 1500-1600 (1983, first published 1971), page 134.

[45] Johnson, G. A. “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” in Johnson, G. A. (Ed) Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy (1997), page 244.

[46] Goffen, R. “Sex, Space and Social History in Titian’s Venus of Urbino,” in Goffen R. (Ed) Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1997), page 66.

hello what year was this article

22 February, 2004

Hello,

I want to cite this essay in my essay for university. Who is this essay by?

I wrote the essay, so the Chicago style reference is:

Laurence Shafe, “The Depiction of the Female Nude in Sixteenth-Century Italian Art”, Laurence Shafe, November 3, 2021, https://www.shafe.co.uk/welcome/art-history/essay_essays/essay_the_depiction_of_the_female_nude_in_16thc_italian_art/