Thomas Howard, 2nd (21st) Earl of Arundel, 2nd (4th) Earl of Surrey, 1st Earl of Norfolk, the ‘Collector Earl’ (b. 7 July 1586, d. 4 October 1646)

Themes

- Collecting in the Early Stuart Period

- Types of Collector

- The Growing Importance of Painting

Collecting

- Collections included curiosities (kunst und wunderkammer), jewels, gold and silverwork, statues, tapestries,furniture, cloth woven with jewels, books and paintings of ancestors and famous people.

- Curiosities were becoming old-fashioned, in 1590 Galileo Galilei wrote that such collections were “the study of some little man with a taste for curios, who has been pleased to fit it out with things that have something strange about them, either because of their age or because of rarity or for some other reason, but are, as a matter of fact, nothing but bric-a-brac – a petrified crayfish, a dried up chameleon, a fly and a spider embedded in a piece of amber …”.

- Renaissance Italian princes – the Farnese, the Medici, the Gonzaga and the Borghese had defined princely splendour and magnificence through their collections of classical statuary and beautiful paintings.

- The European fashion for collecting painting as prestigious works started about 1600.

- English collectors included, in the following periods:

- Elizabeth I — John, Lord Lumley, a bibliophile whose collection was inherited by Arundel

- James I — Prince Henry, Robert Carr (Earl of Somerset), Robert Cecil (Earl of Salisbury) and the founder of modern collecting Thomas Howard (Earl of Arundel).

- Charles I — Arundel, George Villiers (Duke of Buckingham), James Hamilton (Earl of Hamilton) — with others known as the ‘Whitehall Group’.

- Collectors bought through ambassadors (who worked for more than one patron) and their own agents.

- Paintings were affordable. To give some idea of relative prices:

- A labourer eart £10 a year while the lower nobility had an income of about £5,000 a year.

- The lace alone on Princess Elizabeth’s gown was £1,700.

- Charles’s Raphael tapestries were £7,000

- Charles’s Titians were £150-600, and his Durers about £75.

- Cardinal Richelieu’s 250 paintings were valued at 80,000 livres but his silver was valued at 237,000 livres.

- Cardinal Mazarin jewels and gold were valued at 417,945 livres, his paintings 224,873 livres. One gift to the king of 18 diamonds was valued at 1,931,000 livres (1 livre was about 1 shilling, a twentieth of a pound).

- Charles annual income in 1640 was about £900,000.

- During the Commonwealth Sale, 1,410 pictures were sold for £33,690.

- Paintings became valued not for their monetary value but because they support scholarly discussion of antiquity including mythological, metaphorical and allegorical meanings.

- Paintings were unique although copies were rife, so they involved connoisseurship, were tradable and were sought after by the kings and princes of Europe.

Achievements of Thomas Howard

Somewhere in the first two decades of the seventeenth century, a remarkable change in taste occurred in England ‘men began collecting paintings as works of art’

The Earl of Arundel played a key role in bringing about this change through his deep and distinctive love of Italy, Italian culture and antiquity and he became an exemplary English art collector who established a pattern of collecting that became the model for the next two hundred years.

Arundel was part of the cultural change that took place in England in the early Stuart period. His personality, his dedication to collecting and the fortune he spent helped bring about a fundamental change. Arundel made the love of art respectable, particularly morally virtuous art with a classical reference.

He introduced Renaissance ideas of the value of painting and was the first Englishman to show arts and learning added to honour and dignity (see Machiavelli, The Prince).

“His design [drawing] collection was the greatest in Europe, his collection of statues equal to that of a Prince, and his collection of paintings numerous, particularly his collection of Holbein, which was the greatest in Europe”, A Short View of the Life of the Most Noble and Excellent Thomas Howard Earl of Arundel and Surrey, Sir Edward Walker (1705), one time secretary of Thomas Howard.

His collection was not the biggest or flashiest collection but the most erudite. He produced one of the first books on his collection of sculptures.

Thomas Howard — The Person

He had a miserable childhood and never saw his father, who was in the Tower. His family was harassed around the country as they were strict Catholics. His grandfather Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk was executed for supporting Mary, Queen of Scots.

He was old-fashioned and dressed in black clothes and was isolated from the high-life at court and he mixed with scholars.

Some quotations describing Arundel:

- Rubens described Arundel as ‘one of the four evangelists of our art’.

- Horace Walpole called him ‘the Father of Vertu’ in England. (Virtu was civility, grace and manners, learning lightly carried, energy and greatness of action and a love of the arts.)

- ‘Supercilious and proud’, ‘someone who lived within himself’, ‘interested in the mysteries of antiquity’, ‘no one who worked for him got rich’, ‘without any strong religious conviction’, ‘large black piercing eyes’, ‘thin hair and beard’, ‘clothes that were dark and plain but expensive’ and the bearing of the ‘most venerable nobility’, Earl of Clarendon, ‘History of the Rebellion of Civil Wars in England’ (begun in 1641).

- A ‘majestical and grave’ countenance, ‘touchingly gentle with the young’, had ‘patience and dexterity negotiating’, ‘stately Presence’, Sir Edward Walker.

- ‘One of the greatest and most enlightened collectors and patrons England has ever known,’ Christopher White, Anthony van Dyck: Thomas Howard, The Earl of Arundel (California: Getty Museum, 1995).

What Made Him Distinctive?

- His intellectual approach to collecting — he collected works of antiquity that were interesting such as parts of broken sculpture, inscriptions and coins and he had the largest collection of drawings in Europe.

- Strong artistic support by his wife and large inheritance from her father.

- A personal commitment in terms of time and money.

- A network of well managed and competent scholars and

agents:- Rev. William Petty

- Sir Thomas Roe (Constantinople, 1621-4)

- Sir Dudley Carlton (Venetian ambassador, first met him in 1614, by 1616 ambassador in The Hague)

- He met George Gage in Rome (1614)

- Amongst his circle of scholarly and literary friends were James Ussher (Irish scholar who calculated the world was created on Sunday 23 October 4004 B.C.), William Harvey (who discovered the circulation of the blood), John Selden (lawyer and scholar), Sir William Dugdale (antiquarian) and Francis Junius, his librarian, who wrote De pictura veterum in 1637.

- A common early Stuart belief was ‘Do not look for yourself outside yourself’ and stoicism and melancholy were fashionable aristocratic poses and these were attributes of Thomas Howard.

- He ‘distained to mingle in the intrigues of court life’ and found his chief occupation in the formation of his collection.

- However, Roy Strong suggests Arundel was ‘a strong influence on the decision of the Prince [Henry] in the spring of 1610 to emulate the courts of Europe, regarding the collection of works of art as an essential attribute of princely magnificence’. He also had a good relationship with James I (who is not known to have acquired a single work of art), his wife Anne of Denmark (who was passionate about art like her brother Christian IV of Denmark and became godmother to Arundel’s son) and Charles I.

The Life of Thomas Howard

- 1586, born in relative penury at the parsonage of Finchingfield, family in disgrace. His father was a recusant Catholic who was charged with high treason although it was never proved. He was imprisoned in the Tower from 1585 to his death from dysentery in 1595 and never saw his son.

- 1595, aged 9, His father Saint Philip Howard died in the Tower.

- 1598, aged 12, His sister Elizabeth, ‘to whom he was devoted’ died.

- 1604, aged 18, Presented himself at James’s Court supported by his relations.

- 1606, aged 20, Married Lady Aletheia Talbot, daughter the patron Gilbert, 7th Earl of Shrewsbury who had visited Venice in 1576. Met Inigo Jones who designed Essex’s wedding masque Hymenaei and he performed in the masque.

- 1607, aged 21, Arundel House was returned to him.

- 1610, aged 24, Joined Henry, Prince of Wales’s court, Arundel ‘was most particularly favoured’, he called out for him many times from his deathbed. Appeared with Henry in Prince Henry’s Barriers at the investiture. Earliest reference to Thomas Howard acquiring a picture (a gift to Henry).

- 1611, aged 25, Made Knight of the Garter with Charles (then Duke of York).

- 1612, aged 26, Went to Belgium (Brussels, Antwerp, and Spa), Padua and Venice because of threatened consumption. Met Van Balen and may have met Rubens (then known as ‘the god of painters’) and Van Dyck (Van Balen’s apprentice). Met Sir Dudley Carlton ambassador in Venice. Met Thomas Coke in Italy. From Padua rushed back to England for Henry’s funeral.

- 1613, aged 27, Accompanied Elizabeth and Frederick to Heidelberg with Inigo Jones. Went on to Italy for 19 months, the first ‘Grand Tour’ – Milan, Venice, Vicenza, Padua, Florence, Siena and Rome in January 1614. Spent six weeks in a monastery learning Italian first. Became known as a ‘comprehensive collector’ including Titian and Giorgione. William Petty entered his household as tutor, was trained by Arundel and Jones, sent to Italy in 1618 but did not start buying until sent to Constantinople in 1624. Started his collection of drawings with Parmigianino, Scamozzi and Palladio.

- 1614, aged 28, Inigo Jones designed sculpture and picture gallery for Arundel House. It was certainly finished by 1627 when Joachim von Sandrart visited.

- 1615, aged 29, Received into English Church after being brought up a Catholic. Used Sir Dudley Carlton (sent abroad because he was secretary to Gunpowder Plot conspirator Earl of Northumberland) as a buyer. He was in Venice 1610-15, bought 15 Venetian pictures and sculptures for £900 for Somerset just as he was arrested (as his wife had murdered her previous husband Sir Thomas Overbury). Arundel bought the paintings for £200 and Carlton was sent to The Hague where, in 1618, he swapped the sculptures for some Ruben’s paintings.

- 1616, aged 30,By this date ‘collecting was looked on as a gauge of greatness in England.’ Aletheia’s father died, she inherited a third of the estate and his serious collecting started.

- 1617, aged 31, Inherited part Lumley collection including Holbein’s Christina of Denmark.

- 1618, aged 32, Daniel Mytens comes to London at Arundel’s invitation.

- 1620, aged 34, Rubens painted Aletheia Talbot, Countess of Arundel, and Her Retinue in Antwerp when she was on her way to Italy. Van Dyck arrived in October on either Arundel’s or Buckingham’s invitation. Arguably Arundel commissioned Van Dyck to paint Continence of Scipio as a wedding gift for Buckingham alternatively he purchased the frieze fragment later. Van Dyck left in February 1621 not returning until 1632.

- 1621, aged 35, made Earl Marshal of England (the head of the nobility). Commissioned Sir Thomas Roe to find antiquities in Greek and Turkey. Sent his Holbein portrait of Sir Richard Southwell to Cosimo d’Medici; a significant gift and a high point in Arundel’s European reputation.

- 1623, aged 37, rejected James offer of a new dukedom as he wanted his old one restored.

- 1626, aged 40, Francis Bacon died in Arundel’s house after inventing the frozen chicken. Put in the Tower by Charles between March and June because his son had secretly married a kinswoman of Charles without permission.

- 1628, aged 42, Buckingham was assassinated and Arundel returned to Charles’s favour.

- 1629, aged 43, England had become a leading power in the European art market. Arundel published one of the first books on a single collection Marmora Arundeliana by John Selden. In 1637 he planned a similar book on his paintings illustrated by Hollar but it was never published. Rubens visited England in June until March 1630 and he drew Arundel in red and black chalk.

- 1632, aged 46, Arundel brought Elizabeth of Bohemia back to England. Van Dyck returned to England after 11 years.

- 1636, aged 50, Travelled to Vienna to negotiate with Emperor Ferdinand II for Elizabeth. Purchased the library and paintings of Willibald Pirckheimer for 330 thalers. Failed to purchase Ludovisi collection. Met Hollar and returned with him to England.

- 1638, aged 52, Captain general of the Army, first Bishop’s War in Scotland, a humiliating failure. Debts threatened ruin, started the Madagascar plan.

- 1641, aged 55, accompanied the difficult Marie de’ Medici to Cologne, then on to Utrecht.

- 1642, aged 56, accompanied Princess Mary for her marriage to William II of Orange. Did not return but went on to Padua alone.

- 1646, aged 60, died £100,000 in debt and was succeeded as Earl by his eldest son.

- 1655, an inventory of his collection was made. His youngest and his eldest sons argued in court over the collection and it was dispersed.

Thomas Howard’s — Art Collector and Patron

Arundel commissioned portraits by Daniel Mytens, Peter Paul Rubens, Jan Lievens (who shared a studio with Rembrandt, in England 1632-44), and Anthony Van Dyck. Arundel marbles were the most celebrated part of his collection and the introduction of classical nudes into an English garden was highly distinctive. Francis Bacon is recorded as saying ‘Coming into the Earl of Arundel’s Garden, where there were a great number of Ancient Statues of naked Men and Women, made a stand, and as astonish’d, cryed out: “The Resurrection”‘.

Wenceslaus Hollar was brought to England by Arundel and left us detailed engravings and drawings of London between the 1630s and 1660s. In the late 1630s Arundel House contained thirty seven statues, 128 busts and 250 inscriptions.

A full inventory was made in 1655 after his wife had died. Different sources give different numbers possibly because some entries are for multiple items, for example, entry 121, Van Dyck ‘thirty-two portraits in chiaroscuro’. My analysis of Hervey’s list which counts these as multiple items has 799 entries in total of which there are 417 entries for paintings, watercolours and sketches by named artists and 181 entries for the same with no name appended; a total of 598 paintings. He had many more drawings, possibly 5,000. In comparison, Charles had 1,500 paintings when he died. Arundel’s collection includes Durer (sixteen paintings and watercolours including Madonna, a present from the Archbishop of Warzburg), Hans Holbein the Younger (in total forty four works including Christina of Denmark, Sir Henry Guildford, Sir Thomas More and Erasmus). In addition, there were many works by Italian painters including twelve works by Correggio, thirteen entries for Raphael, twenty six for Parmigianino, thirty seven for Titian (including Flaying of Marsyas, and possibly the Three Ages of Man), seventeen paintings by Giorgione, ten by Tintoretto, eighteen entries for Veronese and five entries for Leonardo da Vinci. Other artists included Bassano, Bellini, Bronzino, Cranach, van Dyck, van Eyck, Mantegna, Michelangelo, Mytens, Oliver, Palma Vecchio and Rubens.

Arundel tried to preserve his collection in his will for posterity by stating, ‘all gentleman of virtue or Artists wch are honest’ could see it.However, it was bequeathed to his wife and was dispersed after her death. Some of the sculptures were given to Oxford University by his grandson and are now in the Ashmolean Museum. Some of the other works are now at the Royal Library at Windsor Castle and at Chatsworth.

Quotations Concerning Thomas Howard

“He was tall of Stature, and of Shape and proportion rather goodly than neat; his countenance was Majestical and grave, his Visage long, his Eyes large, black and piercing; he had a hooked Nose, and some Warts or Moles on his Cheeks: his Countenance was brown, his Hair thin both on his Head and Beard; he was of stately Presence and Gate, so that any Man that saw him, though in ever so ordinary Habit, could not but conclude him to be a great Person, his Garb and Fashion drawing more Observation than did the rich Apparel of others; so that it was a common Saying of the late Earl of Carlisle, Here comes the Earl of Arundel in his plain Stuff and trunk Hose, and his Beard in his Teeth, that looks more a Noble man than any of us.” Sir Edward Walker, Arundel’s secretary on his embassy to Germany in 1636.

“There is no name more familiar in the history of art than that of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel and Surrey, who is usually looked upon as the pioneer of art collectors, certainly in England, and as equally distinguished for his connoisseurship and the value of the collections which he made.” L. Cust and M. Cox, Notes on the Collections Formed by Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel and Surrey, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 19, No. 101 (Aug., 1911), pp. 278-286

References

Brown, J. Kings and Connoisseurs: Collecting Art in Seventeenth-Century Europe (London: Yale University Press, 1992)

Cust, L., Cox, M. L., Notes on the Collections Formed by Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel and Surrey, K.G., The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 19, No. 101 (Aug., 1911), pp. 278-286, and Vol. 20, No. 104 (Nov., 1911), pp. 97-100, and Vol. 21, No. 113 (Aug., 1912), pp. 256-258

Downes, K. Arundel’s Quatercentenary: A Book and an Exhibition, Oxford, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 128, No. 995 (Feb., 1986), pp. 161-162

Ford, B., (ed.) The Cambridge Cultural History of Britain, Volume 4: Seventeenth Century Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992)

Hervey, M., The Life, Correspondence and Collection of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1921)

Howarth, D., Lord Arundel as an Entrepreneur of the Arts, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 122, No. 931 (Oct., 1980), pp. 692-694

Howarth, D., The Arrival of Van Dyck in England, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 132, No. 1051 (Oct., 1990), pp. 709-710

Howarth, D., (ed.) Thomas Howard Earl of Arundel: The Ashmolean Museum November 1985-January 1986 (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1985)

Howarth, D., Lord Arundel and his Circle (London: Yale University press, 1985)

Machiavelli, N., The Prince (Harmondsworth: Penguin Book, 1981), translated by G. Bull

Parry, G., The Golden Age Restor’d: The Culture of the Stuart Court, 1603-1642 (Manchester: Manchester University press, 1981)

Shakeshaft, P. ‘To Much Bewiched with Thoes Intysing Things’: The Letters of James Third Marquis of Hamilton and Basil, Viscount Feilding, concerning Collecting in Venice 1635-1639, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 128, No. 995 (Feb., 1986), pp. 114-134

Sharpe, K., The Personal Rule of Charles I (London: Yale University Press, 1992)

Strong, R., Henry Prince of Wales and England’s Lost Renaissance (London: Pimlico, 2000)

Strong, R., The Arts in Britain: A History (London: Pimlico, 2004)

Sutton, D. Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel and Surrey, as a Collector of Drawings-I,II,III The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 89, No. 526/7/8 (Jan./Feb.,Mar., 1947)

Weale, W. H. J., Paintings by John van Eyck and Albert Durer Formerly in the Arundel Collection, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 6, No. 21 (Dec., 1904), pp. 244-245 and pp. 248-249

Wedgwood, C., The King’s Peace 1637-1641 (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1983)

White, C. Anthony van Dyck: Thomas Howard, The Earl of Arundel (California: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1995)

How Collections Were Hung

Allegory with the House of Muses,Alessandro Salucci (1590-1655/60)

Frans Francken (1581-1642), Sebastiaan Leerse in his Gallery, Oil on panel, 77 x 114 cm, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

Willem van Haecht (1593-1637), The Picture Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest, 1628 Antwerp, Rubenshuis

Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625) and Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Allegory of Sight,, c. 1618, oil on wood, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Portraits of Arundel

Daniel Mytens the Elder (c. 1590-1647), Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel and Surrey, c.1618, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, London

Daniel Mytens the Elder, Aletheia Talbot Countess of Arundel, c.1618, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, London

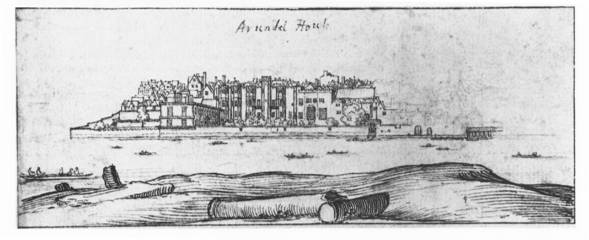

Wenceslaus Hollar, Arundel House, Royal Library, Windsor

Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641), Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel, 1620-21, oil on canvas, 102.8 x 79.4 cm,The Getty Museum

Peter Paul Rubens, Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, 1629-30, Oil on canvas, 122.2 x 102.1 cm, purchased 1898 from Colnaghi, London, Boston, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The head and shoulders Rubens portrait is in the National Portrait Gallery, London

Anthony van Dyck, Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel and Surrey with His Grandson Lord Maltravers, 1635, oil on canvas, Duke of Norfolk, Arundel Castle, Sussex

Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait drawing of Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel, 1629-30, Pen and brush in brown ink over black and red chalk, washed over with white body-colour, 28 x 19 cm, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Anthony Van Dyck, Lord and Lady Arundel, the ‘Madagascar Portrait’, 1639, oil on canvas, 135 x 206.8 cm, Arundel House

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Portrait of Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel, 1629-30, National Gallery

Examples from the Arundel Collection

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543), Christina of Denmark, 1538, oil on oak, 179 x 82.5 cm, National Gallery, London

Hans Holbein the Younger, Anne of Cleves, c. 1539, Paris, Musee du Louvre

Hans Holbein the Younger, Nicholas Kratzer, 1528, oil on wood, Paris Musee du Louvre

Hans Holbein the Younger, William Wareham, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1527, oil on wood, Paris, Musee du Louvre

Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Sir Henry Wyatt, 1527, oil on wood, Paris, Musee du Louvre

Giorgio da Castelfranco (Giorgione, c. 1477-1510) and/or Tiziano Vecelli (Titian, c. 1485-1576), Pastoral Concert (Fete Champetre), 1508-9, oil on canvas, 110 x 138 cm, Paris, Musee du Louvre

Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677) after Durer, Woman with coiled hair (Portrait of Katharina Frey), 1646, etching, 218 x 173mm, Royal Academy of Arts, London, Holding two flowers symbolic of love.

Albrecht Durer (1471-1528), Young Woman With Bound Hair (Portrait of Katharina Frey), c. 1497, Oil on canvas, 55 x 42 cm, Berlin, Gemaldegalerie

Tiziano Vecelli (Titian), The Flaying of Marsyas, 1575-76, oil on canvas, 212 x 207 cm, State Museum, Kromeriz

Tiziano Vecelli (Titian), The Three Ages of Man, 1513-14, oil on canvas, 90 x 151 cm, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

Aletheia Talbot (wife Thomas Howard)

Alethea Howard, Countess of Arundel (1585 – June 3, 1654), nee Lady Alethea

Talbot, was the wife of Thomas Howard, 21st Earl of Arundel. The youngest daughter of Gilbert Talbot, 7th Earl of Shrewsbury and his wife Mary, Alethea was the sister of two other countesses: Mary Talbot Herbert, Countess of Pembroke, and Elizabeth Grey, Countess of Kent. In September, 1606, she was married to Thomas Howard, and they had three children:

- James Howard, Baron Maltravers (1607-1624)

- Henry Frederick Howard, 22nd Earl of Arundel (1608-1652)

- William Howard, 1st Viscount Stafford (1614-1680)

Aletheia was one of three daughters of one of the richest families in England and when her father died she inherited his wealth. She collected independently of her husband. Her father had travelled in Italy and was an ambassador in Paris. Hardwick Hall was designed by Robert Smythson for her grandmother Bess of Hardwick who died in 1608.

Arundel used her money to buy back Arundel House and she financed their trip to Italy in 1614. In 1620-23 she travelled independently and attempted to go to Spain.

She bought Tart Hall in 1633 and used it to entertain her Catholic friends. Nicholas Stobe was used in the conversion, like the Queen’s House for Henrietta Maria, which was also built by Stone. Lady Arundel refused to become Church of England so in 1641 she went into voluntary exile. Somerset House housed a Catholic so she could have used Arundel House but Tart House was more isolated, 1.75 miles away (near what is now Buckingham Palace) close to St. James Palace. Lady Arundel paid for the refurbishments. It was built in 1613 and she converted it and dedicated the third floor to art with two long picture galleries. The only portrait of Arundel was of him as a child in her bedroom. The 1641 inventory showed her collection was mostly Italian, mostly Venetian art and she had 16 landscapes. The house had wall paintings including Pheoton.

She wanted to emulate the Queen. She chose Diana mythology, the huntress. She owned a Titian in 1630, which was unusual and positioned her as a connoisseur interested in Venetian colouring. Her only statues were small bronzes designed to be enjoyed by connoisseurs. Bassano and Cranach were also in the room. There were three painted ceilings, unusually innovative like a Roman villa. Artemisia Gentileschi may have worked for Aletheia. In 1639 Artemisia was in London when her father Orazio died.

Aletheia collected Indian textiles and porcelain and the existence of Tart Hall shows she was independent, she died in 1654. She had broken every convention of court by travelling across Italy on her own.

Collecting Paintings

Older history books say picture collecting started with Charles I, newer books with James I and recent research Elizabeth (see early collecting in Elizabeth’s reign by Richard Williams).

See quote 1. It was very unusual to name a painter, a mention of history as a subject (not just portraiture), you will increase your magnificence (i.e. standing at court) by buying this art. Previously magnificence was demonstrated by spending money on expensive clothes not by buying canvas with oil and pigment on it.

Charles collection is well described in the literature but the key themes are:

- From the 1620s he had an interest and started building a collection.

- 1625 Rubens called Charles the “greatest amateur of art of all the princes of

the world.” - 1622 Venetian ambassador referred to Charles “he loves old paintings especially those of our city.” So word was getting around. This was not flattery but a private communication.

- 1623 he went to Madrid to woo the Infanta, sister of Philip IV (who was only 16 when he came to the throne) only 18 in 1623 and Charles was only 23.

Charles would have heard of Philip’s collection, the largest in Europe, with over 2,000 paintings. Charles took the Duke of Hamilton (who was painted by Mytens), he was restrained (he wore black with red stockings), possibly influenced by the Spanish fashion for wearing black.

Balthazar Gerbier went (agent for Buckingham) to advise. Endymion Porter also went to advise, his grandmother was Spanish. He arrived in disguise. They put on a tour and Charles made purchases such as Titian’s Woman in a Fur Wrap and he was also given paintings by Philip such as a Titian, Giambologna (in the V&A) and Veronese Mars and Venus.

The visit exposed Charles to the greatest collection in Europe and the largest collection of Titian’s (who had painted for Philip II). His coup in the 1620s was to acquire the collection of hte Duke of Mantua (the greatest in Italy)., the Gonzaga collection. Raphael La Perla (the Holy Family), Caravaggio Death of the Virgin Mary (it caused a scandal as he used a prostitute as a model). Triumphs of Caesar by Mantegna – every collector in Europe wanted them so it caused a sensation.

We don’t know how the paintings were displayed, were they linked by painter or subject? In Privy Palace in the first room there were 12 pictures, 11 by Titian (including the Pissaro altarpiece), Nude Girl in Fur Wrap, Entombment of Christ, Venus with the Organ Player, all in the same room.