Inigo Jones, Part 2, The Queen’s House, Greenwich

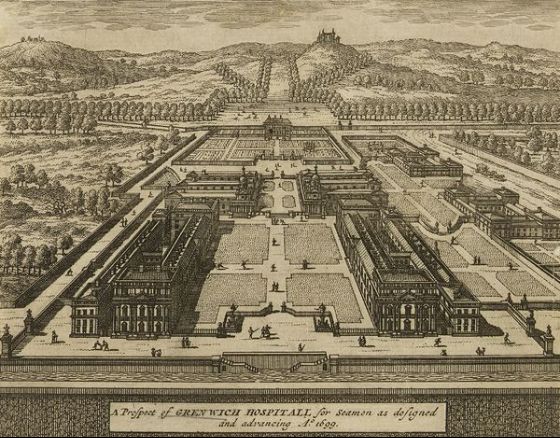

JOHANNES KIP. 1752 painting showing royal hospital with Queen House in the

distance. Probably painted from the same view-point as the later Canaletto –

Isle of Dogs.

The site

The site of the Queen’s House at Greenwich is thought to have formed part of a

recognisable estate as far back as the 8th century; it would therefore be wrong

to view it in isolation.

The site at Greenwich has been associated with monarchs for many hundreds of

years from 871 AD when Alfred the Great inherited Greenwich from his father

Ethulwulf, to 1491 when Henry VIII used the palace at Greenwich – as a popular

residence – ‘a rural retreat from the heat and stench of central London’; to

James I. who settled the manor of greenwich on his queen in 1613.

See the hand-out for a more comprehensive list.

The park

Refer Johannes Kip 1752 slide.

The park itself is a medieval creation which today covers 190 acres of landscape

which has been carefully manicured since the early 15c.

In 1433 Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester obtained a licence to enclose the land as a

park; this resulted in the building of a 12′ high brick wall measuring over 2

miles in length.

At the site of the Queens House, the wall was built on both sides of the road.

Following the re-siting of the road to the North in 1697-9 the walls abutting

the Queens House became redundant for all but the containment of deer within the

park.

Due to an overlay of the Blackheath by the Greenwich beds, there are several

natural sources of water within the park. The Duke of Gloucester built an

aqueduct 1434 to utilise this natural resource.

The park has been open to the public since 1705, although altered, it retains

some of the strong formal lines of 17century layout.

The first part of 17c saw considerable activity in the park and Royal Palace

with the creation of new gardens and the building of the Queens House.

The garden

Queen Anne of Denmark

In the first decades of the 17th century, during Queen Anne’s time, ‘the gardens

had been an artifice of masonry, planting, grotto and water features’. Salomon

de Caus, a designer from the Low Countries, was employed to develop the garden.

De Caus was a member of Prince Henry’s Court from 1610 – 1612. At Greenwich he

was involved in extensive re-planning of the gardens. A ‘new garden’ later known

as the ‘Queens garden’ was created. By 1612 the gardens comprised new orchard,

lodge and grotto. A plan of 1694, in Bold, shows the garden as being to the N.W.

of the House with a tilt yard occupying the N.E. section, a path divided them.

Queen Henrietta Maria

By 1635 building work on the Queen’s House was almost complete allowing work to

be done outside the house. 1637 Henrietta Maria paid '1,500 for extensive garden

work to be carried out. The mannerist garden created for Queen Anne was not

fashionable enough for Henrietta Maria. She was influenced by French garden

design. A terrace was constructed and paved between 1635-6 on the North side of

the house. This provided a viewing-point for the gardens. The two new iron

balconies installed on the North side outside the bedchamber and cabinet may

also have been added to provide additional viewing points overlooking the

gardens.

The Queen sent to France for fruit trees and flowers. During the same year, a

wall-mounted fountain of French design was installed (John Webb later changed

the Tuscan features of the fountain to Ionic – maybe in keeping with the Loggia)

The Queens House building; influences

It is repeatedly written that the Queen’s House constitutes the ‘first essay in

pure renaissance design in England’. It was designed by Inigo Jones soon after

the last of his study tours to Italy in 1613-14 and offerered an opportunity to

give form to his dreams of architectural design. Although the Queen’s House was

intended to be a Renaissance building, and there are a number of Italian

borrowings, Jones was too good an architect to rely on one source.

The details of plan and elevation derive from Jones studies of Andrea Palladio

and Vincenzo Scamozzi.

The chief influence is thought to be Vincenzo Scamozzi (1552-1616), the most

important of Palladios Italian followers who Jones met and from whom he acquired

an extensive collection of architectural drawings.

SLIDE – VILLA POGGIO

Lorenzo de Medici’s villa at Poggio a Caiano near Florence (finished by Giuliano

da Sangallo in 1485) has a similar plan shape. The Medici villa also has an open

colonnade like that built into the park front at Greenwich.

The oblong plan is also similar in shape to the villa Aldobrandini, (no slide)

incorporating a cube hall and circular stairway. The whole effect of the

building is long and low with no gravitation to the centre.

SLIDE – 20th CENTURY SECTION – CHETTLE

SLIDE – Plan showing the 5 PHASES

Building phases

The Queen’s House, designed by Inigo Jones, was constructed on either side of

the Deptford to Woolwich roadway on the site of an old gate-house. It became

known as Jones ‘curious devise’ which later writers called the ‘House of

Delight’. It comprised 2 buildings united by a covered bridge of stone. Due to

the circumstance of the public road, It is in effect a ‘double house’ , with the

northern half in the garden, the southern half in the park. Apparently the idea

of building over or above a road was unusual but not unique. Jones did not

intend to make anything spectacular out of the bridge.

The Queen’s House took many years to complete. This makes any discussion about

the chronology of building rather complex task. John Bold’s plan helps one to

understand how the building progressed.

A brief chronology is as follows:

– In 1613 James I. formally granted the manor and palace of Greenwich to Queen

Anne of Denmark. In 1616 the foundations were laid. Very soon after this she

began to plan improvements in association with Simon Basil the Surveyor of the

Kings Works. The project was not only initiated by Anne but owes a lot to her

ideas, she showed an interest in the most up-to-date architectural ideas from

the continent.

– In 1615 Simon Basil died and Jones was appointed Surveyor of the Kings Works

having already been Surveyor to Henry Prince of Wales until 1612.

– 1616 Jones prepared at least 2 prototypes for Queen Anne. He also drew a side

elevation showing the road passing under the centre of the house. In essence, an

‘H’ shaped house.

In the October of 1616 work began and continued for 18 months. The former

gate-house that stood over the park gate was demolished, foundations dug, stone,

bricks and timber assembled.

– 1617 – Work of the Queens House began.

– 1617-19 the North Building comprising ground floor and basement, and the South

building with just a ground floor were erected. In this first phase 2 separate

buildings were built, one each side of the road. They were unconnected at this

stage. REFER TO THE FIRST PHASE OF THE PLAN.

– 1619 – Queen Anne died therefore building as planned was not finished and ten

years were to pass before work commenced again. Following Anne’s death, the

House was given to Prince Charles who retained it after his accession in 1625.

– 1629 – Greenwich Palace was given to Queen Henrietta Maria. Charles I. granted

possession after his accession and their marriage. Henrietta, the daughter of

Henry IV and Maria de’ Medici grew up in a court that was strongly influenced by

Italian culture; she commissioned Inigo Jones to complete the building work.

– 1629-30 – work resumed on the Queens House. New building must have taken place

in that year perhaps in preparation for the second floor. REFER TO THE SECOND

PHASE OF THE PLAN

– 1629 – 1638 an upper storey was added to each building

– 1635 – It is reported that the Queen went to see completion in May when it was

far advanced.

– 1636 – much of the carving was executed.

– 1637 – Jones made 2 designs for chimney breasts.

– 1638 – final payment made to Wickes which marks completion of the main

building.

– 1661 – the North side terrace was added.

SLIDE – NORTH FACADE

The house measures 115′ in length on North and South sides. 117′ in length, East

and West sides.

North facade

The north facade is of two storey elevation over a basement storey. It is

composed of 3 bays. This effect is created by a slight projection of the middle

portion, which also marks out the width of the Great hall. The two outer bays

have 2 window openings each side making 7 windows in all at each level. In the

original design the sill-line of the ground floor windows of the rooms on either

side of the Hall was higher than now. They had mullioned and transomed window

frames glazed with lead lights.

The 7 windows on the first floor have moulded stone sills and architraves.

Cornices rest directly on the architrave at the heads. The middle window is

semi-circular in shape; above it is a marble tablet with the inscription ‘HENRICA

MARIA REGINA 1635’ engraved into it. The 4 outer windows have one voussoir on

either side of a projecting keystone. The 3 middle openings have 2.

On the first floor, iron balconies projected in front of the flanking windows,

these added to the charm of the piano nobile. From the North front could also be

seen the corniced roof of an octagonal lantern that rose above the interior

circular stairs.

Positioned centrally, between a curving flight of steps is a semi-circular

headed doorway of rusticated stone with architrave and key stone that leads

straight to the cellars through a second doorway under the main wall of the

house. This basement is brick-vaulted and runs the full length of the building.

It is possible that it was initially left unfinished, and then relegated as a

storage area when the building was commissioned in the 1630s. It should be noted

that the circular tulip stair began at ground floor level. Therefore there was

no internal stairway from the basement to the ground floor. It may be thought

that the entry to the ground floor was intended by way of a stone or wooden

external staircase rising from the garden in straight flights to either side of

the entrance door. There are no traces of these stairs which may have been

wooden constructions. THEY APPEAR ON THE FIRST PHASE OF PLAN.

The original conformation of the steps seemed imitative of Pratolino. When

built, they curved round to face each other, framing the door into the basement,

but are now in horseshoe form.

An Ionic entablature with balustraded parapet crowns the facade of the North.

SLIDE – SOUTH FACADE

South facade

The south facade faces the open spaces of the park, in its design, Inigo Jones

gave full play to his knowledge of Renaissance architecture. His notes allude to

Scamozzi’s villa Molini near Padua as a source of study for the park front. The

south facade consists of 2 tiers; there is no basement storey but the 3 bay

pattern seen on the North facade recurs.

The ground floor has nine openings, a wide central doorway and two narrow

windows on either side are grouped closely together. In the upper tier Jones has

incorporated in his design a 5 bay Italian loggia using the Ionic order. It

occupies the entire width of the central bay. This first floor loggia was almost

certainly the first to appear in England. The loggia links the public to

private, inner to outer, has a symbolic as well as architectural function. SLIDE

INTERIOR OF LOGGIA.

The central intercolumniation is widened to correspond with the doorway below.

The bases of the columns rest on low plinth blocks. Between the columns are set

stone balustrades and these balusters are repeated below the sills of the

flanking windows of the facade. Above the entablature the balustraded parapet

repeats the treatment of the north front.

In 1708 lowering of sills of ground floor windows is more apparent than

elsewhere. These windows now compete in importance as on the other fronts with

the upper ones destroying the architectural function of the rusticated

ground-floor walling – that of a podium carrying the more elegant upper storey

or piano nobile.

Facade E. and W.

The East and West elevations are similar to the North in general line, a

slightly projecting centre embracing 3 windows, flanked by 2 windows on either

side. Before the addition of the Doric colonnades, the East and West fronts

showed as the ends of 2 ranges of building projecting 45′ in front of the

segmental arch of the bridge.

Roofs

The roofs are lead covered flats.

Chimney stacks brick rendered and have recessed angles.

Building materials

The house is built of brick, faced with rusticated stone up to first floor level

on the N. and S. sides with corresponding rustication in the brick-facing of the

E. and W. sides and the elevations to the roadway.

Above the string-course all external walls are of plain brickwork. Window

dressings and main cornice are of stone. Above the cornice the parapet is formed

of a stone balustrade on the two main facades. The plinth is of Kentish Rag, the

main facing of Portland Stone. The retaining wall of the terrace is faced with

portland stone and has a double offset at the bottom – now partially buried.

The brick facing was at first covered with a thin coating of lime lined-out with

stone jointing. This made the house appear of a startling whiteness.

SLIDE – GREAT HALL

REFER TO HAND OUT SHOWING PLAN WITH ROOMS WRITTEN IN

Interior

Utility

In the first phase of construction the Queens House would not need kitchen and

utility rooms since these were in adjacent buildings.

North building

The Great Hall

The Great Hall functioned as grand reception area for those entering, before

climbing the Tulip stairs to the piano nobile and as such provides a

centre-piece of the Queen’s House. (It should be noted that an equivalently

grand single-story hall was also intended for Anne of Denmark).

The form it takes is of a 40′ cube occupying 2 storeys reflecting Jones

enthusiasm for the cube and double cube rooms. It has a cantilevered gallery at

first floor level that surrounds the hall. Details of the brackets and balusters

closely resemble those of the gallery of the Banqueting Hall at Whitehall.

Wooden brackets resemble the masque stage sets for ‘Britannia Triumphans’ of

1638. The frieze and cornice of the Hall and the enriched beams of the ceiling

are of pine. The floor, laid by Nicholas Stone and Gabriel Stacey in 1636-7 is

of black and white marble. When finished in 1630s the Queen’s House ceiling and

gallery were painted white with gilded enrichment.

SLIDE – GREAT HALL CEILING PANELS

Ceiling panels were to be completed with paintings by Orazio Gentileschi who

came to London in 1626 at the invitation of Charles I. The decoration was

comprised of nine canvasses of the Allegory of Peace and the Arts under the

English Crown in celebration of Charles I. reign (now in Marlborough House).

In the south wall of the gallery are two windows looking on to the roadway and a

central doorway framed in Portland stone. The four doorways in the side walls

are finished with stone architraves and entablatures. In the middle of the south

wall is a semi-dome crowning an apse, within which are steps leading to the

middle salon built under the bridge when the roadway was diverted.

A chief function of the Great Hall was as sculpture gallery. In 1638-9 workmen

were employed to prepare settings for antique statues. Zachary Taylor made 10

carved pedestals to receive marble statues. John Hooker was paid to turn 15

great pedestals of olive timbers with bases and capitals at the same time.

The statues were brought to Greenwich from other palaces, some from Oatlands.

Some were from the former Gonzaga collection from Mantua.

The finest works included Bacchus and Sabena, Adonis, Apollo, Perseus, Diana,

Jupiter and Venus.

The most important sculpture to be housed in the niche of the Great Hall was by

Gian lorenzo Bernini; a bust of Charles I. Van Dyck’s triple portrait is

believed to have provided the model. The original was destroyed by the Whitehall

fire of 1698.

SLIDE – TULIP STAIRCASE

The Great Hall provides access to the tulip staircase. This was the first

geometric, self-supporting spiral stair to be built in Britain, a departure from

masonry design. It is thought to be modelled on one by Palladio. Jones would

have been familiar with precedents at Andrea Palladio’s Convento della Carita.

The stairs were completed c1635 at the height of the European tulip craze. The

stairs are continued beyond the first floor to the polygonal turret which

accessed the leads. It has a continuous balustrade of wrought iron of remarkable

beauty consisting of square vertical bars separating scrolls bearing leaves and

tulip flowers with double scrolls on the landings. (The extension to the

basement is 19c).

Bedchamber 1st floor west side N.Front

If completed the Queen’s bedchamber would have been distinguished as one of the

most magnificent of the decorative schemes devised by Inigo Jones and Henrietta

Maria; embodying in permanent form the legend of choice of the Caroline Court –

Cupid and Psyche. Mottoes and angles of the ceiling spell out an appropriate,

idealised message for a Stuart bed chamber. 'Mutual fruitfulness, the hope of

the state burns forever with pure fragrance'. A theme central to divinely

ordained rulers of a perfect state.

All paintings are intact except the central panel. in 1637 Guido Reni was to

design a symbolic work for the bed-chamber. First choice of subject was Cephalus

and Aurora but as it depicted a rape it was thought unsuitable. Second choice

was Bacchus and Ariadne. The central panel now contains an Aurora – painter

uncertain.

SLIDE – GUIDO RENI – EXAMPLE ONLY of an Aurora painted for Casino rospiglion in

Rome.

The ceiling coving was painted by either John de Critz or Matthew Gooderick. It

is thought to have been influenced by Caprarola and Palazzo Te.

SLIDE – CORNICE SECTION

The anti-room leading from the bedchamber was thought to function as a private

chapel for Henrietta Maria, a practicing Catholic.

Queens withdrawing room – East side North front

This room would have embodied in permanent form the legend of the Caroline Court

– Cupid and Psyche and was one of the most richly ornamented rooms in the house.

SLIDE – CEILING OF WITHDRAWING ROOM

Painter likely to have been Jakob Jordaens; the intention was for 22 paintings

to cover ceiling and walls but only 8 were completed; they were installed in the

early 1640s.

Letters that passed between England and the Netherlands in 1639 and 1640

indicated that some of the ceiling panels might be painted by Rubens with cupids

holding garlands of roses.

The room was already richly hung with paintings e.g. Gentileschis Lot and his

Daughters (since moved to the great Hall.) Artemisia’s Tarquin and Lucretia. Van

Dyck’s portrait of the Archduchess Isobella and a large Flora.

SLIDE – ORAZIO GENTILESCHI EXAMPLE ONLY ‘Rest on Flight to Egypt’ (slide not

available)

chimney pieces

SLIDE – CHIMNEY PIECE – POSSIBLY FOR QUEENS BEDROOM

17th century French design is evident in the chimney piece and overmantle of

Henrietta Maria’s house. Italian designs were not available due to the climate –

no demand in Italy. Inigo Jones designed one in 1637 ‘for the room next to the

back stairs’ – likely to be the Queen’s anti-room/chapel and another ‘for

Greenwich’. They come from ‘Architectural book for Chimney’s’ by Jean Barget

published in 1633. Another was for the bedchamber and another for the Cabinet

room behind the tulip stairs.

Intention and function for the Queens House;

General initial function

At the outset the new building was required to fulfil the same function as the

Tudor Gate-house that it was replacing, that is to span a public right of way.

Being formed of an ‘H’ it may have been perceived as belonging to the tradition

of the ‘devise’ as a visual symbol. The most important characteristic of the

‘devise’ was an ingenuity of form and plan, as such they were often built as

lodges or retreats. But although ‘curious’, the Queen’s House did not belong

with this tradition. The completed Queens House is thought to represent not a

transition in architectural style but a perfect embodiment of a change in

fashion, a move away from the medieval palace toward provision of an intimate,

secluded space; now considered to be one of the most remarkable domestic

buildings of its time in England.

The ideas and intention of Queen Anne and Henrietta Maria were of the greatest

importance in evolving the design of the Queens House, but the needs of Queen

Anne were different to those of Henrietta Maria for whom it was finished.

It was unfinished when Queen Anne died and this has led to conjecture as to the

intended purpose, but it is thought that a dual function was intended – a place

of reflection and retreat, and to serve a ceremonial role as an entertainment

suite.

Its intended purpose changed during the course of its long period of

construction and decoration and for Henrietta Maria’s it was a secret house

where she could retire comfortably for extended periods.

Paradoxically, while the new grander route into the building via a stepped

terrace is in keeping with Anne’s intended desire to combine public and private

uses in her house, it is not so appropriate for Henrietta to use it as a private

retreat.