We can see Jacobean tomb sculpture in Westminster Abbey and churches up and down the country. For example, Anne Stanhope, widow of the Duke of Somerset, Protector in the 1550s, died 1587

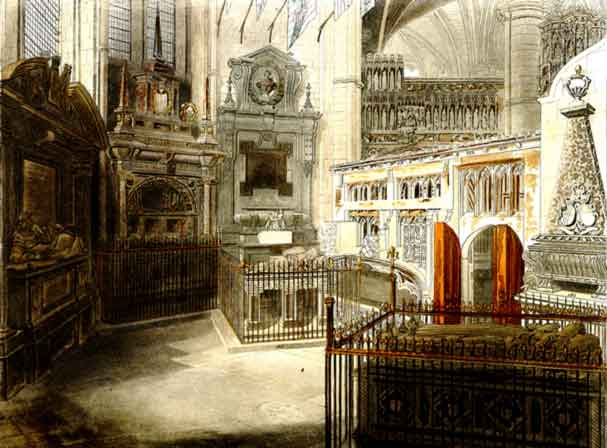

Sir John Puckering, d. 1596 (privy-counsellor to Queen Elizabeth, and four years chancellor, in which office he died. This monument, like many others of the same period, wears a most sumptuous appearance. It is lavishly adorned with statues, columns, arches, obelisks, animals, and scroll-work of various marbles, enriched with painting.)

Funerary monuments did not change a great deal between the reign of Elizabeth and James I. Monuments tended to get larger and larger until they eventually reached the ceiling. Following the Reformation and the loss of religious items sculptors had the following opportunities:

- Tombs

- Fireplaces, chimney pieces and so on.

- Busts

- Garden ornaments, fountains and figures.

We find busts in some inventories of the late sixteenth century. For example, the inventory of George Lumley includes images that include the Lumley horseman (a life size equestrian statue) and busts of Henry VIII, Mary, Elizabeth and Edward VI which still survive. We know the inventory drawing were done in the 1590s so the busts were probably just before this date.

An example of a fountain that still survives is the Venus Fountain at Bolsover although the Venus is dumpy and crude without classical proportions. Another (that does not survive) was the Fountain of Diana a full length garden sculpture in Lord Lumley’s garden at Nonesuch Palace.

During James I reign interest developed in the classical look.

The major problem for sculptors was at the time of the Reformation their main source of income was removed and all the religious sculptures were smashed. One late fifteenth century medieval English sculpture of St. Margaret was discovered in the nineteenth century in Essex as it had been walled over.

Of course, sculpture in medieval times up to this period was brightly painted and would have looked garish to us as they often used contrasting stripes to paint the walls, such as red and blue stripes. This lack of assignments was common all over Nothern Europe but in England there was a thirst for funerary monuments.

Protestant refugees from France and the Netherlands settled in England in Soutwark, which was outside the limits of the City and so outside the control of the guilds. Guilds, such as the Painters and Stainers guild for painters were against all foreign artists and could prevent them working within the City.

The tomb of Margaret Lennox, grandmother of James I, died 1578 is in Westminster Abbey. Why were ornate tombs like this produced, particularly at a time of Protestant austerity in religious matters. There were the secular concerns of making a statement about the importance of the family through memorializing the dead expensively and with the iconography of their power. Memento mori (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memento_mori) and the dance of death (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dance_of_death) were late medieval approaches to death with their associated imagery that still survived in the late Elizabethan and early Stuart period. A typical effigy is often a blank face like a mask rather than a strongly characterised portrait.

Before the Reformation a role for the tomb was the focus for prayers for the dead in purgatory but the Reformation did away with the concept of Purgatory and whether a person went to Heaven or Hell was determined by the “will of Christ” and was pre-ordained before a person was born. It was therefore inappropriate to pray for the soul of a dead person as they were already doomed or saved. Someone who had a tomb built in York with a plaque asking for prayers for his wife was called up to answer for his Popist views. It has therefore been suggested that the bland anonymous faces were not because the sculptor could not produce a likeness but to create a distancing effect so visitors would not feel sympathy and fall into the trap of saying a prayer for their soul. The hands in prayer were to perhaps reassure the family that the person was one of the elect chosen to go to heaven.

Status was paramount. Like many tombs, the Lennox tomb has:

- Heraldry, coats of arms, the coronet of the Countess and the robes of a Countess.

- A coronet over the head of her eldest son, Lord Darnley (who married Mary Queen of Scots and was father to James I)

- Precious materials, particularly gold.

- Her sons are wearing accurately portrayed suits of armour suggesting chivalry.

- Inscriptions give the family history and the personal achievements of the person.

- Often “modern” Renaissance scroll and ornament is included.

- Most important is where the tomb is located (in the case of the Lennox tomb in the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey.

There were an increasing number of monuments to children at this time and child mortality remained extremely high even for royal children. James I two daughters who died young are in Innocents Corner in Westminster Abbey – Princess Mary died in 1607 and Princess Sophia who died in 1606 aged only two years three days. Sophia is shown in a crib. These tombs were built by Maximillian Colt. James I also commissioned him in 1605-6 to built a tomb to Elizabeth I. Colt also worked at Hatfied House for Sir Robert Cecil and he produced typical Netherlandish work of this period. All Colt’s work was done in Southwark and in general tombs were carved in sections in Southwark and shipped all over the country and assembled on site.

James I commissioned a tomb from Cornelius Cure (pronounced “Quowr”) which was completed by his son William Cure the younger in 1607 for Mary Queen of Scots (James I mother). The sarcophagus was based on the design of a sarcophagus by Rovezano.

Benedetto da Rovezzano (b Canapale, nr Pistoia, 1474; d Vallombrosa, nr Florence, c. 1554). Italian sculptor, active also in England. Benedetto was in England by 1524, remaining until at least 1536. There he made a tomb with many bronze statuettes for Cardinal Wolsey, which Henry VIII later claimed for himself (destr. 1646; marble, gilt bronze and touchstone; sarcophagus now part of Nelson s tomb in St Paul s Cathedral, London). He was a typical Florentine sculptor. Italian sculptors stopped coming to England at the time of the Reformation and only started creeping back in James I reign so England was cut off from Renaissance developments except through the French and Netherlandish Protestant exciles.

The inscription on Elizabeth’s tomb is mostly about James – stressing his right to rule and his legitimacy. James was trying to honour both Elizabeth and Mary and give them equal prominance (even though Elizabeth ordered the execution of Mary), one i on the left and the other the right of the Chapel. Strangely and inexplicably there is no monument to James I in the Henry VII Chapel and there never was. In the nineteenth century permission was given to look in the crypt beneath the tomb of Henry II and the sarcophagus of James I was found there. Both kings founded new dynasties (Tudors and the Stuarts) so perhaps it was thought appropirate they were buried siad by side. James I did have a very elaborate and expensive funeral and the ceiling of the Banqueting Hall (see by Rubens is based on the ascension of James I. The funeral was much more important than the tomb as it marked the smooth transition of one king to the next and as had been found with Lady Jane Gray a mistake could lead to catastrophe.

During the funeral an effigy of the king represented their body politic (entirely separate from the corrupt body physical). These effigies are still stored in the crypt at Westminster Abbey and they were made from a face mask in plaster (a death mask) attached to a wooden head which was fixed to a frame stuffed with straw and then dressed in the king’s clothes. The king had two bodies, the physical and the body politic (the role of kingship) which never dies but passes on into the next king.

Robert Cecil’s tomb (died 1612, tomb built 1615) by Maximilian Colt in Hatfield Church in his robes of the Knight of the Garter. Robert Cecel had approved the tomb design before he died and it was not uncommon for a tomb to be built up to twenty years before death. This became awkward if the person’s wife dies first and they remarried as the extra wife had to be squeezed in and is sometimes shown standing at the back. At the bottom of Cecil’s tomb is his body physical shown as a skeleton. His body politic above represents his fame and achievements which continue after death. The tomb is only black and white unlike the multi-coloured tombs of the pervious period. This represents a change in aesthetic taste at this time (although brightly coloured tombs continued throughout James reign). It is associated with an interest in classical sculpture as can be seen in the four female figures surrounding the tomb.

There is a fashion for plaster ceilings in James I reign and classical mythology in uncoloured plaster – was this to do with Protestant imagery and not wanting to make the images too realistic. We still have the same feeling today about plaster and marble sculpture and feel that pure white is “correct” even though in classical times the sculptures were polychromed.

Epiphanius Evesham is significant as he marks a break. He lived in Paris between 1600-1615 as a painter and sculptor and so he was exposed to the Mannerist French style. For example, of this style see the Diana of Ana in the Louvre – a women with extended limbs with her arm around a stag.

Monument to Lord Teynham, 1632, at Lynsted Kent shows mourners by Epiphanius Evesham. It has a great sense of movement, it is a relief sculpture of high quality with a strong sense of narrative. This was a Catholic family and we see cherubs in the clouds. IS it possible Evesham was a secret Catholic? All the figures are strongly individual so it is possible they are portraits.

The range of people commemorated during this period went down through the ranksof Knights down to academics. Dean Goodwin, a university lecturer at Christchurch Oxford is shown in the standard format for academics, half length (perhaps because it was cheaper), with academic gown and a cap holding a book. At this time statues like this were fully polychromed.

There were new poses such as Peregrine Bertie, at Spillsbury in 1610. Note the strapwork used.

Nicholas Stone

Mason sculpture, 1587-1647, a British sculptor who kept a detailed account book from 1631-1642 which survives in the John Soane Museum and was published by the Walpole Society. It records 80 funeral monuments many of which survive. It is packed full of information about costs, dates and timescales. HE came from Devon, trained in Amsterdam and was therefore exposed to sophisticated sculptural techniques. Merton College, Oxford, Thomas Bodley, 1615, (of Bodleian Library fame) has a tomb by Stone were the pilasters are a pile of books, it cost 100. The figures around the tomb represent the arts and sciences.

1617-20 Lady Kerry, white marble, very individual face and hands, Stone was an unusually talented sculptor.

Sir John Donne posed for a tomb in a shroud on top of his urn.

Francis Holles, 1622, Westminster Abbey, dressed like a Roman soldier.

Julio de Medici in Michelangelo’s Medici tomb in Florence seems to be the model so it is possible he saw a print (he never went to Florence).

There was a steady increase in quality of architectural ornament at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Note the swags on top of the Banqueting House in Whitehall were carved by Stone for Inigo Jones and incorporated in the tomb of Holles.

1633, John and Thomas Lyttelton, Stone again, classical influence, a tomb for two brothers who drowned. The narrow pleats of the drapery shows the classical influence.