Inigo Jones defined a style that was to last for 200-300 years but in the years before this change it was a period of rapid innovation and change.

An English country house required a small army of workmen – masons, carpenters, glazers (glass was still extremely expensive and “light and airy” was a term of high praise as it still is today), plasterers, plumbers (Who worked with lead), roofers (who also worked with lead, which was extremely expensive), specialist masons for sculptured work, joiners (finer work than carpenters), bricklayers, sometimes slaterers (for tiled roofs), metalworkers and smiths for hinges, nails and metalwork.

Some craftsmen were part of a local regional tradition. For example, in some parts of the country without local stone there would be local bricklayers who would use a kiln to make the brick on-site. One of the biggest expenses was the cost of transport over the terrible roads. Plaster work had to be done on site but some items, such as wainscot, be done off-site and transported. Most wall panelling, for example, was made in London. This was because with items that could be seen the latest London fashions were often desired.

Local craftsmen had local styles, e.g. plasterers had their own moulds that can be used to identify a particular workshop. Local craftsmen would build, for example, a fireplace in the local style. Inigo Jones, for the first time, designed all the items including the fireplaces.

Designs were copied from drawings made by craftsmen, often handed down from father to son, from pattern books (Italian, French, Netherlandish and German) and from the patron’s ideas. In the late 16th century the influx of Netherlandish artists fleeing the persecution of the Protestants influenced English design.

One negative impact is that we often see badly carved nudes resulting from the local craftsmen’s inept attempt to copy Italian designs.

In the end it was the patron who had the final and often the first say in the design. Pattern books were typically not in English and could only be read and could only be afforded by the patron.

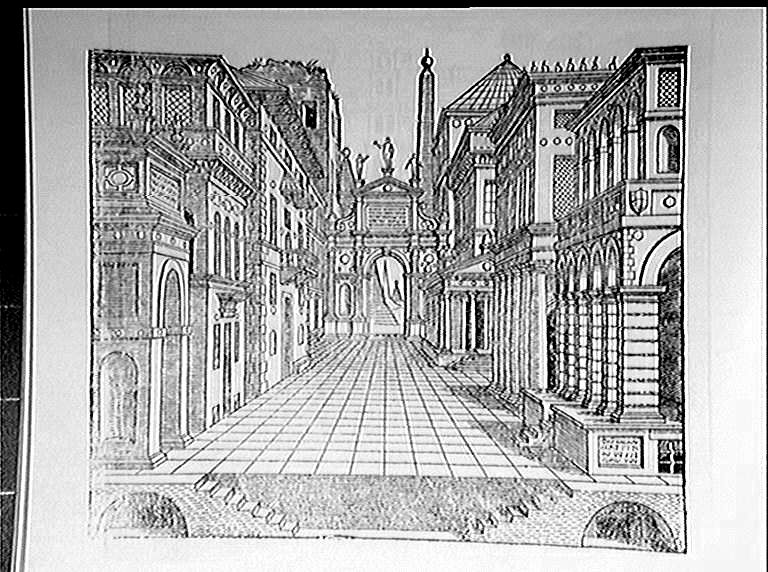

Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527-1606) began his training as painter in Amsterdam. Later, in Mechelen, he assisted with the construction of the triumphal arches for the “merry entry” of Charles V and Philip II. He studied the works of Vitruvius and Serlio. As an architect, he assisted with the fortifications of Antwerp. After Antwerp was conquered by Spain, he continued his work in Germany and Prague and in 1601, he returned to the Netherlands, where he remained until his death. He published a number of books with clear text and drawings and they were often reprinted, and had significant influence on the architecture of Northern Europe. De Vries became fashionable from the 1580s onwards.

From the middle of the 15th century onwards pattern books became popular and there were early example in the early 15th century.

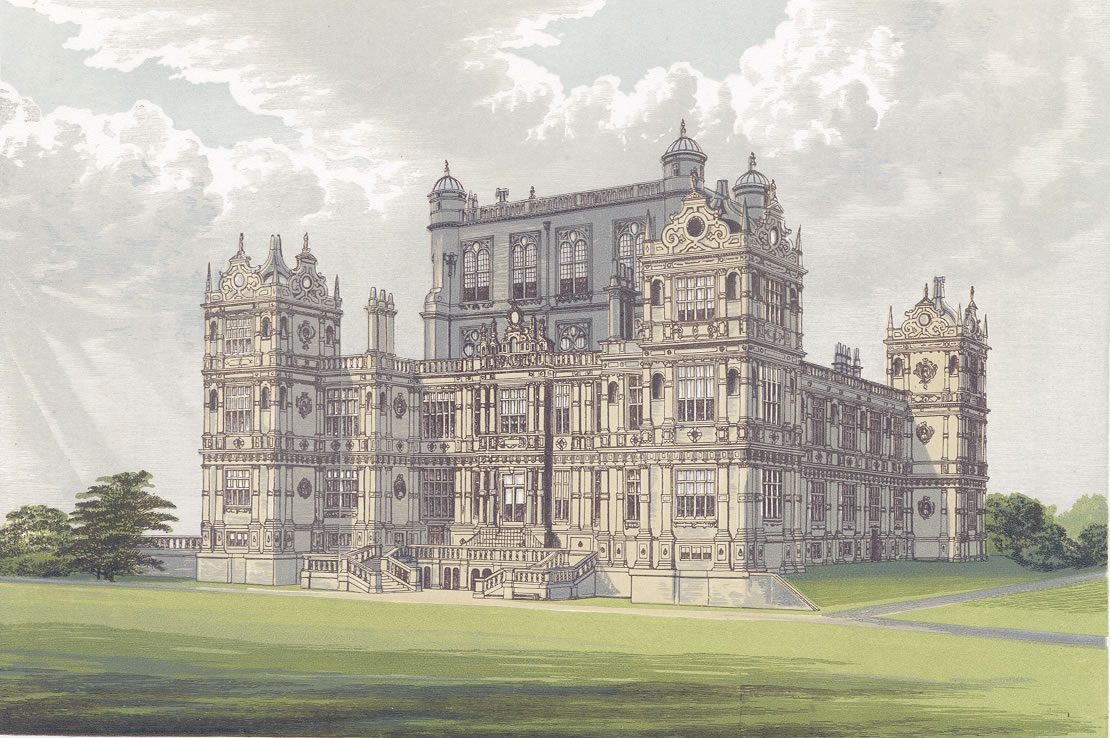

Wollaton Hall. Note the strapwork (the scrolls that look like leather straps) that derives originally from Fontainebleau. Anthony Wells-Cole’s book Art and Decoration in Elizabethan and Jacobean England (1997) shows how the design in pattern books were used on all types of craftwork. Wollaton Hall’s patterns, for example, were all copied from de Vries.

In late 16th century England there was no such thing as an architect as we understand it today. The term is first used as we understand it in the early 17th century. “Platt makers” would design a house by producing what we call a plan and sometimes “uprights” or what we call exterior elevations. A platt maker was someone who produced a large scale plan.

Wollaton Hall Plan.

Robert Smythson (produced the designs for Wollaton Hall (sometimes attributed to John Thorpe).

Smythson, Robert, 1536?-1614, English architect of the Elizabethan era. From 1568, Smythson was freemason to John Thynne in finishing (1567-75) the country house Longleat, Wiltshire. Striking in its symmetry, its outward-looking plan, and its numerous and large windows, it revealed a new concept of domestic design, showing admirably refined use of classical detail. His chief work was Wollaton Hall, Nottinghamshire (1580-88). Although he followed the pattern of Sebastiano Serlio and other Renaissance continental architects, he was ingenious in his adaptations. (Columbia Encyclopedia)

It was even possible to request a design by post and the designer would send it but never journey to see or oversee the building of the house. Wollaton’s accounts shown the master mason, Robert Smythson, was a debt collector. We also think he designed Hardwick Hall remotely.

Some patrons were obsessed by architecture. Sir Thomas Thynne visited the building of Longleat every day and he once asked for a complete frontage to be pulled down and rebuilt as it was not perfect. Some patrons in the 17th century designed their own houses although we assume it was little more than a sketch. It was acceptable for a gentleman to design a house in this way as it was associated with the military skill of designing fortifications. However, a gentleman would never paint as this was a lowly craft occupation. Hardwick Hall is extremely complex – a work of true genius.

Architectural drawings were handed down from generation to generation and we know of one drawing of a rose window from this period that could have been drawn many years before, perhaps from the building of the cathedrals. Practical building knowledge about how thick to make walls, support structures and so on were handed down from father to son in a workshop.

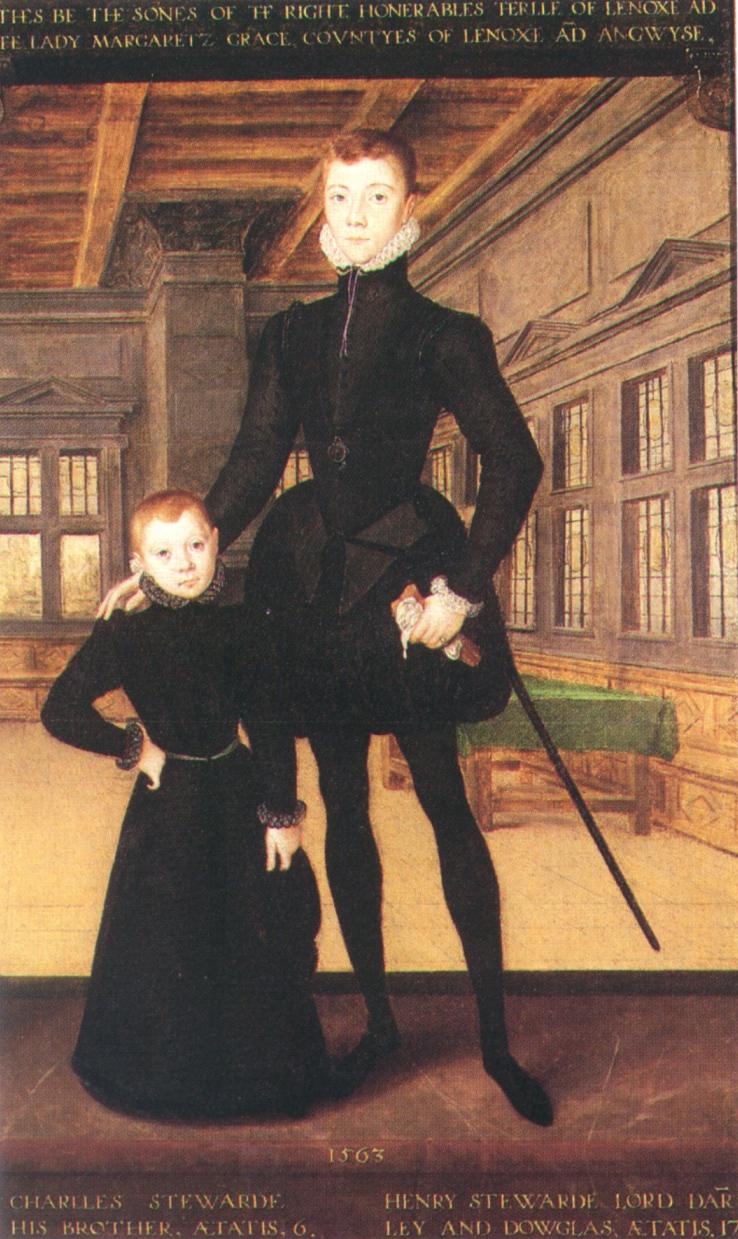

1563, Lord Darnley (who married Mary Queen of Scots and was finally either blown up or strangled or both) has a portrait with his son in a room that is copied from an existing Dutch engraving.

Sebastiano Serlio (the Italian designer) book Architettura (1537-51) was translated in English in 1611 but the book was first used in the mid-16th century. For example, the design above the fireplace in Longleat by the French carver Alan Maynard is copied from Serlio’s book. He may have been shown the book by his patron Thynne.

The fireplace in Wollaton Hall was also copied from Serlio’s book in the 1580s. The fireplace in the long hall at Hardwick (1590s) is also from Serlio.

In the early 17th century Hans Dieterlin, a German designer, produced his own book which has even more ornate designs than de Vries. So over ornamented as to be grotesque. His work had a vogue, e.g. Charlton House in Greenwich in 1607-12, built for Adam Newton, the personal tutor to Henry. Patrons were, of course, also trying to show off their own learning.

Note

A “device” is a catch-all term for anything that is witty, unusual or eye catching. For example, a poem that is acrostic (the first letter of each line forms a word downwards) is a witty device. A meat dish fashioned to look like a fish is a witty device.

Buildings could incorporate a device. For example, John Thorp designed a building shaped like his initials “IT” (at the time the letters “I” and “J” were interchangeable). He left a complete book of designs which was published by the Walpole Society and is available in the John Soane Museum. He was a surveyor who made accurate plans of existing buildings and he also designed buildings.

The most famous witty device was the triangular building built for Sir Thomas Tresham. He was a notorious Roman Catholic and the building, which he described as a warriner’s lodge (a rabbit keeper) has a triangular plan three gables.

Lodges were very inventive as unlike the main residence a lot of freedom was allowed in trying out new designs. 1563, John Shute – The First and Chief Grounds of Architecture was published in England in English on the five classical orders.

Hatfield House is the best preserved Jacobean House in the country in Hertfordshire (open after Easter). It was built for Robert Cecil (later Lord Salisbury and Chief Minister to James I and the son of Lord Burghley, Chief Minister to Elizabeth I), 1607-12.

Hatfield House begins in about 1485, when John Morton, Bishop of Ely, built Hatfield Palace.One side of it, containing the Banqueting Hall, still stands to the west of the present House. Henry VIII’s children were brought up in the house and later Elizabeth was held a virtual prisoner there until she heard of Mary’s death while sitting reading under an oak tree in the grounds. Robert Cecil, the second son of Burghley, had been brought up to succeed his father as chief minister of the Crown. He held this position under Queen Elizabeth, and later was responsible for arranging that James, King of Scotland, should succeed Elizabeth peacefully. As long as he lived he remained James’s chief minister and dominated English politics. It was he who was finally responsible for the discovery and suppression of the Gunpowder Plot. James I did not care for the Old Palace as a house; he preferred Theobalds (“Tibbolds”), the residence of Robert Cecil, afterwards 1st Earl of Salisbury (1563-1612), and he proposed an exchange. Robert agreed. In 1607/08 he pulled down three sides of Hatfield Palace and built himself the present House in what was then a modern style at a cost of at least £38,000. The main designer was Robert Lyminge, but the plans were modified by the advice of several others, including, it is thought, young

Inigo Jones.

The elaborate door shows the different orders one above the other. This elaborate door was originally the back door and the original front door is much plainer. The back door later became the front when a drive was built through the park. It is also speculated that Inigo Jones had a hand in the design of the loggia.

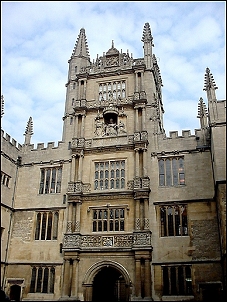

Cobham House, Kent, 1591-4 shows three orders, Wadham College, Oxford shows four.

The Bodleian Library has all five classical orders.

Some people started to visit Italy but not Sir Robert Cecil. The use of the classical orders shows classical learning, at the bottom are the more rustic orders and as one rises they become more refined. The servants were on the ground floor and the most important rooms generally on the first floor.

Robert Lyming designed Blickling Hall which has many similarities.

Hatfield House plan. The entrance leads into the screens passage into a sideways hall.

It differs radically from Elizabethan houses. We still had the Royal progress but we now have a monarch and a queen to house.

Courtiers therefore needed houses with two wings and king and queen bedchambers. The great hall was there (see Henry VIII’s Great Hall at Hampton Court) for eating and dining. in medieval times everybody ate there but by Henry VIII’s time only servants ate in the great hall. The passage often seen above and called a minstrel gallery was actually to keep an eye on the servants. The lord ate in the high chamber or in a parlour.

Audley End’s great hall has an elaborate screen with a hammer beam roof (the hammer are the vertical struts and the construction is like an inverted ship’s hull). 1603-1616. But it is a vestigial hammer beam and anachronistic by this stage as it is completely fake. It does not support the ceiling but hangs from it and is just there for status. It is an old-fashioned medieval arrangement.

The dais end of the great hall was originally raised for the lord and was sometimes used for business, such as seeing the tenants to collect rent, or for plays. It was also the entrance to the stairway up to the important apartments. In the 16th century stairs were very cramped but in the 17th century they became elaborate.

The great hall is two stories high and is to the left of the entrance.

Barrington Hall 1550s plan shows they tried to match the two storey great hall windows with the other side. In medieval times there would be unsymmetrical two storey windows for the great hall and no attempt at balance.

1600, Burton Agnes, Yorkshire, has the great hall in the centre with an entrance porch balanced by a fake porch.

Charleston Hall, Warwickshire, has the same thing with a central hall. They did not want to give up th screen passage and therefore had a problem balancing the front.

Audley End is enormous today but we only see about half of the original building which was built by the Lord Treasurer. The hall is in the centre and the entrance is to the left.

Eventually we see the entrance in the centre.

Holland House has an entrance in the centre and there is no raised end in the hall and two fireplaces at the end of the hall. A bit of the building remains in Holland Park (it was hit by a bomb in WWII). It is technically a villa as it was outside London and, like a Lodge, therefore had more freedom to experiment with the design.