English portraiture was transformed during the reign of James I from the Elizabethan style to that of van Dyck. This essay covers early Jacobean portrait painting. At the turn of the century there were two major workshops:

- John de Critz the Elder

- Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (pronounced “Gerats”)

Both these artists were brought over as children in the 1560s to escape the persecution of Protestants by the Spanish Inquisition. Many other painters and sculptures came over at the same time. These two artists founded painting dynasties, intermarried and had workshops south of London, in Southwark. Isaac Oliver married into the Gheeraerts family (he was his step brother-in-law). The Sergeant Painter (the title for the Court Painter) painted all the works at the Royal Places.

James I’s two portraits of 1605-6 from the workshop of John de Critz are typical of the portraits it produced of the king. The show the “house style” and maybe a “house pattern”, that is a standard portrait that was copied for every new painting. Assistants were taught to copy the house style exactly so that they could work on the same picture with different styles being visible. Once a pattern was approved by the king the workshop could produce as many as it wanted of that image. We know that James I loathed sitting for his portrait.

In the National Portrait Gallery there are cut-outs used to transfer by pricking and pouncing with black charcoal dust in a bag. They also copied the pattern freehand and they also used the equivalent of carbon paper. They covered a sheet of paper with carbon black, turned that side onto the picture surface and then placed the picture to be copied on top and drew with a stylus. The pressure would leave a black line of carbon behind. The technique was called carbon transfer. Infra-red reflectography can be used to reveal the under drawing and the black dots associated with pricking and pouncing can be clearly seen. The two pictures above are drawn freehand, one full length and the other three-quarter length. Head and shoulders portraits could also be purchased and all these portraits of the king were in high demand both by his subjects and for foreign courts.

Full length portraits came into fashion in the 1590s (Holbein’s Ambassadors was an exception) and it suddenly became very fashionable. There are many reasons, maybe late 16th century dandies saw another opportunity to show off their legs. More seriously it has a stronger presence and creates an impact. This was particularly important in the new houses being built with long portrait galleries. Previously full-length portraits were reserved for royalty so when it became more widespread it had a status attached. It also enables the accoutrements of the sitter to be shown. As these paintings were all about the demonstration of power this was particularly important, perhaps more important than showing a good likeness. There was also an increasing move to using oil on canvas rather than painting on wood panels. There had been a long tradition of using canvas but it was painted using distemper (coloured pigments in animal glue). At the end of the 16th century in England there was a change to painting on canvas using oil and canvas was cheaper than wood. John de Critz worked for Francis Walsingham and later Robert Cecil (Secretary of State) so although he did not work for royalty he was working for important people in the court.

John de Critz, Earl of Southampton, 1603. He was the right-hand man of the Earl of Essex who was executed for treason but the Earl of Southampton ended up in the Tower.

Marcus Gheeraerts was step brother-in-law of John de Critz and painted a full length picture of Elizabeth I in the 1590s. Gheeraerts is the critical painter as he represents the turning point from the Elizabethan style to the new European style.

The Duke of Norfolk’s collection has a painting of an unknown lady in a red dress with red curtains. Marcus Gheeraerts started a trend of painting pregnant women. It was done in case the woman died in childbirth. (Arnolfini, 1435, it is disputed whether she is pregnant as it was the fashion, this is indicated by the fact that van Eyck’s virgin saints are also shown looking pregnant).

Tate Britain has Marcus Gheeraerts pregnancy portraits. He is breaking with the earlier Elizabethan aesthetic. Above we see a picture of an unknown lady with a made up coat of arms (Tate Britain). It is late 1560s by Hans Eworth (pronounced “U-earth”). Elizabethan white face was fashionable, there is a jet black background to accentuate the face, no modelling of the face, and a brightly lit white oval face. Gheeraerts has modelling and less fine detail. The range of tonality was reduced in Elizabethan

painting and increased with the painting of Gheeraerts.

The Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I, 1588 (the year of the Armada). Elizabeth has a huge costume to create a sense of power. It is attributed to George Gower, Serjeant Painter. But were portraits of Elizabeth representative? Portraits had to represent the monarchy, she gets younger and younger as the years pass until she ends up almost as a young girl. She was the Virgin Queen and it was not polite to raise the question of the heir. These portraits were like icons evoking the power of the office rather than the real person.

Gheeraerts sits his figures (Robert Deveraux, Earl of Essex, 1596 above) in a landscape. This was an innovation in Britain at the time.

Nicolas Hilliard portrait miniature of the Earl of Cumberland, 1590, is a cabinet miniature (i.e. a larger size, approximately A4). The buildings are 16th century

Whitehall Palace, the other is Cadiz where he had just won a battle against the Spanish. The miniature is garish, the Earl of Essex is painted with a lower range of tones. A deliberate extension of the legs to look elegant in a mannerist style. The Earl of Essex is a more naturalistic landscape and is sober in tone.

Roy Strong, the dominant scholar in this area,

describes the style of this picture as a medieval illuminated manuscript style.

Marcus Gheeraerts, Thomas Lee, sombre, subdued and a melancholic mood.

Tom Derry, 1616, Anne of Denmark’s court jester by Gheeraerts is a remarkable image.

Sculptural modelling with a discernable light source. This new fashion for painting illusionistically was called “Curious Painting” by the Elizabethans and was fashionable in the 1590s. Literature is full of references to it, they were bowled over by how lifelike it was. It represented a cultural shift and paintings were described and being able to speak to you.

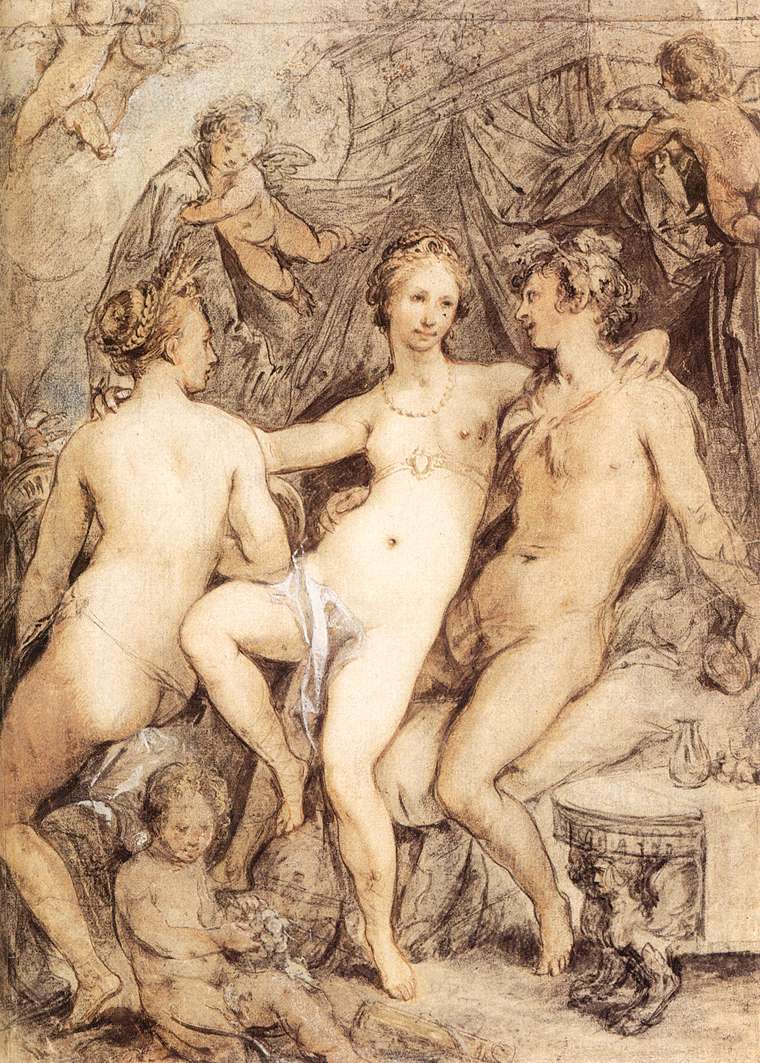

Isaac Oliver was Gheeraerts step brother-in-law and this is a jaunty

self-portrait. It is unusually a three-quarter length portrait miniature. A “O”

with a line through it was his monogram. He gets the format from European

painters. Goltzius prints would have influenced Oliver.

Hilliard’s design for Elizabeth’s Great Seal for Ireland is formal and

austere.

Isaac Oliver’s drawing of the female figure is relaxed with a sense of

movement. We are missing 10 years of Oliver’s life so he may have travelled

abroad. His drawings contain Dutch, French and Italian mannerist influences, his

style is extremely eclectic.

For example, this Nymphs and Satyrs of 1610.

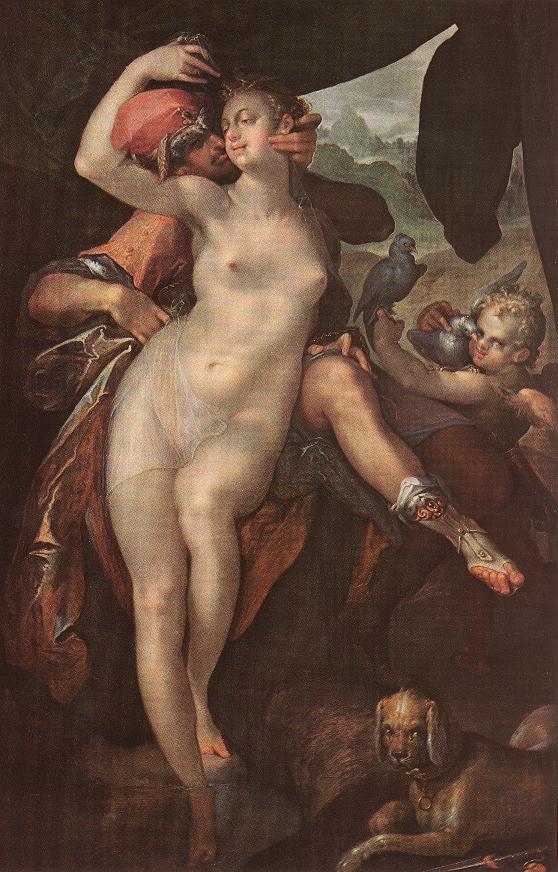

It can be compared with Goltzius, Venus Between Ceres and Bacchus of 1599

or Bartolomeo Spranger, Venus and Adonis. Spranger was painting in the court of

Rudolph II in Prague and used complex distorted mannerist poses for effect.

This portrait miniature of Christ by Isaac Oliver in the V&A is a blurred,

idealised image like a Correggio.

Oliver’s portrait of Sir Arundel Talbot is important as written on the back is

1596, by Isaac Oliver in Venice. This is very surprising as much of Italy was

out of bounds to the English. Rome was forbidden by law and all foreign travel

had to be approved by the King.

William Larkin, London Born, only emerged recently. One of the most popular

painters at the time he never received royal patronage but he was used by all

the senior nobility. His work is startling, Kenwood House has this portrait of

Richard Sackville, Earl of Dorset, 1613. It is dazzling, as large as life-size

and he manages to combine the detail so loved by the Jacobeans with the Curious

Painting style. 1613 was the year Princess Elizabeth married and written

accounts say that the Earl of Dorset was the one that stood out because of his

dress.

In 1603 James I cancelled sumptuary laws that had determined what each rank

could wear. This meant that there was no limit on what the lower classes could

wear so the top aristocracy had to go to extremes like this to show their rank

and power. This fashion did cause derision at the time, remember this was the

time of the Puritans.

These are known as “Curtain and Carpet” portraits. It is a Turkish carpet and

the old Hindu “swastika” symbol can be seen. It also shows the lace, this was

the golden age of English lace making. Every stitch was painted (unlike say

Rembrandt). An inventory of all his clothes survives and shows that he did own

exactly all these clothes which are listed and described in detail. The

brilliant white surface was obtained by applying a double ground. White chalk

mixed in animal glue was applied, allowed to dry and then scraped down, twice.

Also note the string tied round her wrist. This was common and was used to tie on a ring that

was a family heirloom so that it would not drop off. This suggests that rings were not adjusted

in size but were passed down unchanged from generation to generation. The string therefore

symbolized an important family.

In 1617 and 1619 two accounts show this painting of Lady Catherine was purchased

for '30 (would this be about '30,000 today?)

The same carpet is repeated in 10 other Larkin portraits. Diana Cecil, Countess

of Oxford’s dress is deliberately slashed and a picture of her sister Anne Cecil

shows the identical picture and dress with just a different face.