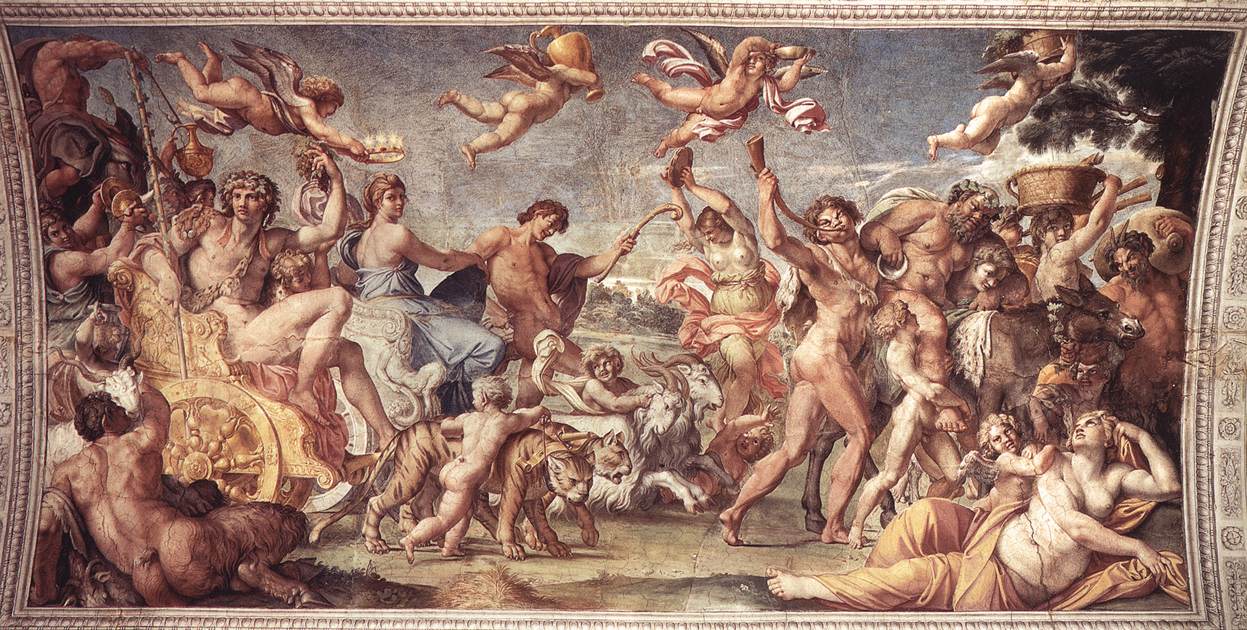

Slide 1: A Carracci, Triumph of Bacchus (Farnese Gallery)

The huge ceiling in the reception room of Palazzo Farnese, painted just as the seventeenth century was beginning, was part of a great cycle of decorative paintings on the theme The Loves of the Gods, which Carracci painted for Cardinal Odoardo Farnese. Annibale Carracci transformed the reception room into a shining collection of classical pictures. In fact, the decoration was not intended to be a single scene, but imitated a collection of framed paintings surrounding the main scene. This was the Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne which fills the centre of the ceiling.

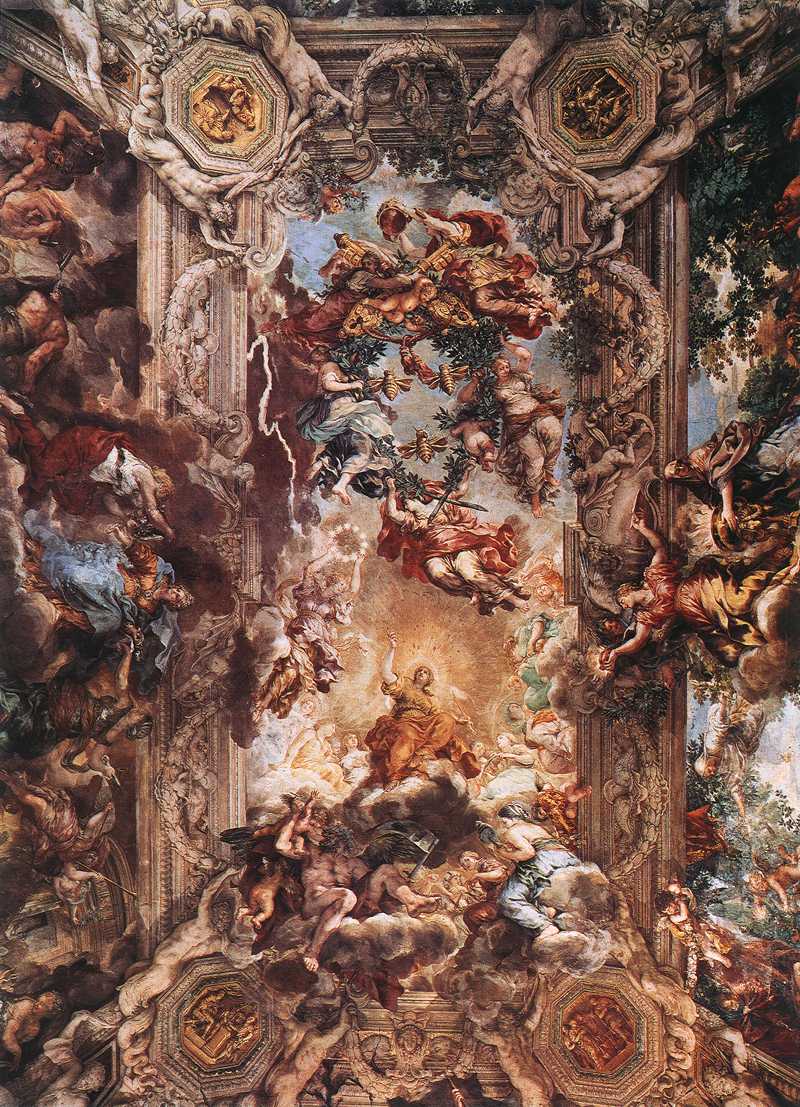

Slide 2: A Carracci, Rome, Palazzo Farnese, Gallery vault, general

Slide 3: Guercino, Aurora (Casino Ludovisi)

Slide 4: P. da Cortona, Divine Providence (Palazzo Barberini)

Slide 5: P. da Cortona, Div Providence, det. Fall of Giants

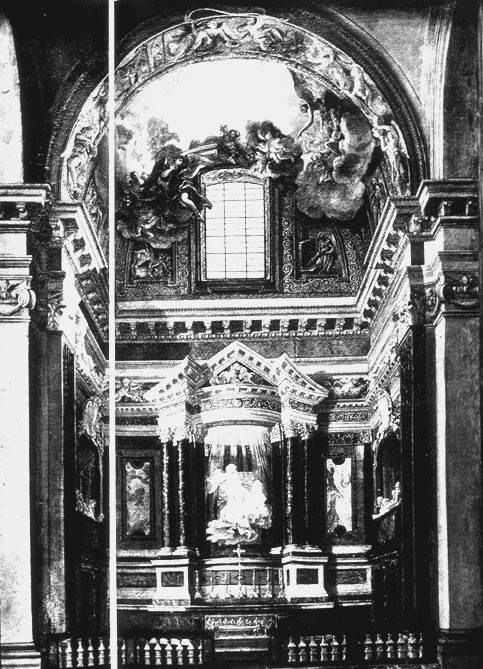

Slide 6: P. da Cortona, SM in Vallicella, cupola/apse(image not found)

Slide 7: P. da Cortona, M&C in Glory (SM in Vallicella)(image not found)

Slide 8: Baciccio, Name of Jesus (Il Gesu, nave vault)

Slide 9: Baciccio, Name of Jesus (Il Gesu), detail A.(image not found)

Slide 10: Pozzo, Apotheosis of St Ignatius (S. Ignazio)

LIGHT

Slide 11: Caravaggio, Calling of St Matthew (S. Luigi de’F.)

This painting is the pendant to the Martyrdom of St Matthew and hanging opposite in the Contarelli Chapel of the San Luigi dei Francesi, the French Church in Rome. It was particularly appropriate to both the place and the time, for Rome’s French community had something to celebrate: Henri IV, heir to St Louis, had recently converted to the faith of his ancestors.

The subject traditionally was represented either indoors or out; sometimes Saint Matthew is shown inside a building, with Christ outside (following the Biblical text) summoning him through a window. Both before and after Caravaggio the subject was often used as a pretext for anecdotal genre paintings. Caravaggio may well have been familiar with earlier Netherlandish paintings of money lenders or of gamblers seated around a table like Saint Matthew and his associates.

Caravaggio represented the event as a nearly silent, dramatic narrative. The sequence of actions before and after this moment can be easily and convincingly re- created. The tax – gatherer Levi (Saint Matthew ‘s name before he became the apostle) was seated at a table with his four assistants, counting the day ‘s proceeds, the group lighted from a source at the upper right of the painting. Christ, His eyes veiled, with His halo the only hint of divinity, enters with Saint Peter. A gesture of His right hand, all the more powerful and compelling because of its languor, summons Levi. Surprised by the intrusion and perhaps dazzled by the sudden light from the just – opened door, Levi draws back and gestures toward himself with his left hand as if to say, Who, me?], his right hand remaining on the coin he had been counting before Christ’s entrance….

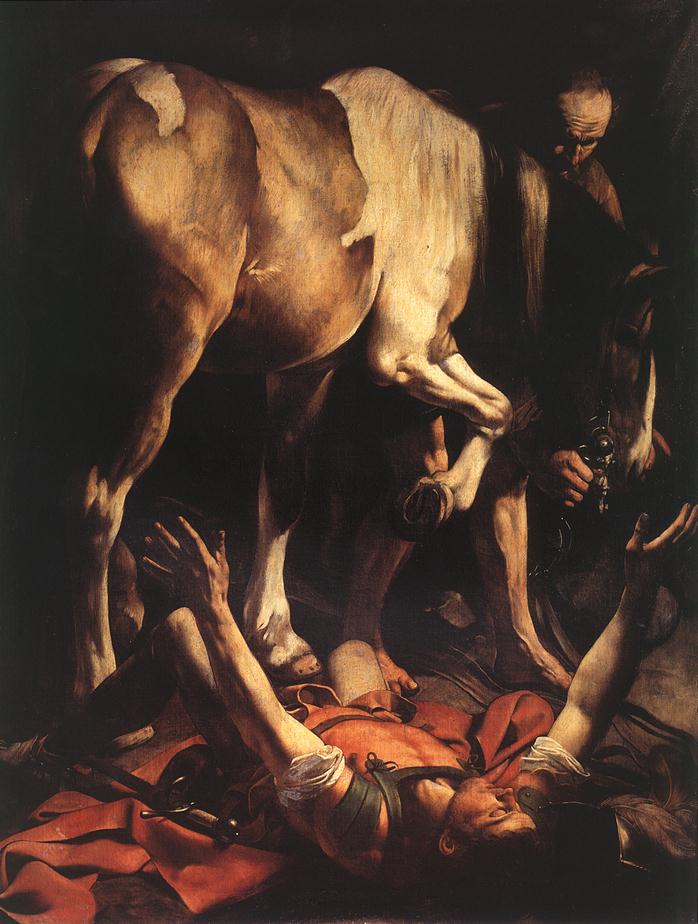

Slide 12: Caravaggio, Conversion of Saul (S.M. del Popolo)

In 1600, soon after he had completed the first two canvases for the Contarelli Chapel, Caravaggio signed a contract to paint two pictures for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo. The church has a special interest because of the works it contains by four of the finest artists ever to work in Rome: Raphael, Carracci, Caravaggio and Bernini. It is probable that by the time Caravaggio began to paint for one of its chapels, The Assumption by Annibale Carracci was in place above the altar. Caravaggio’s depictions of key events in the lives of the founders of the Roman See have little in common with the brilliant colours and stylized attitudes of Annibale, and Caravaggio seems by far the more modern artist. Of the two pictures in the chapel the more remarkable is the representation of the moment of St Paul’s conversion. According to the Acts of the Apostles, on the way to Damascus Saul the Pharisee (soon to be Paul the Apostle) fell to the ground when he heard the voice of Christ saying to him, ‘Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’ and temporarily lost his sight. It was reasonable to assume that Saul had fallen from a horse. Caravaggio is close to the Bible. The horse is there and, to hold him, a groom, but the drama is internalized within the mind of Saul. He lies on the ground stunned, his eyes closed as if dazzled by the brightness of God’s light that streams down the white part of the skewbald horse, but that the light is heavenly is clear only to the believer, for Saul has no halo. In the spirit of Luke, who was at the time considered the author of Acts, Caravaggio makes religious experience look natural. Technically the picture has defects. The horse, based on Dürer, looks hemmed in, there is too much happening at the composition’s base, too many feet cramped together, let alone Saul’s splayed hands and discarded sword. Bellori’s view that the scene is ‘entirely without action’ misses the point. Like a composer who values silence, Caravaggio respects stillness. Both this and the following painting appear to be second versions, for Baglione states that Caravaggio first executed the two pictures ‘in another manner, but as they did not please the patron, Cardinal Sannesio took them for himself’. Of these earlier versions, only The Conversion of St Paul survives.

Slide 13: Bernini, Ecstasy of St Theresa, det., light source

The Cornaro Chapel, located in the Northern transept of the Church is composed in a theatrical way. The group of Saint Therese and the angel is situated in a framed niche lighted beautifully from an unidentifiable source. The sensual character of the ecstasy aroused erotic associations and generated moral reservations from the second half of the eighteenth century. However, for contemporaries it had met all religious and moral requirements.

MOVEMENT AND DRAMA

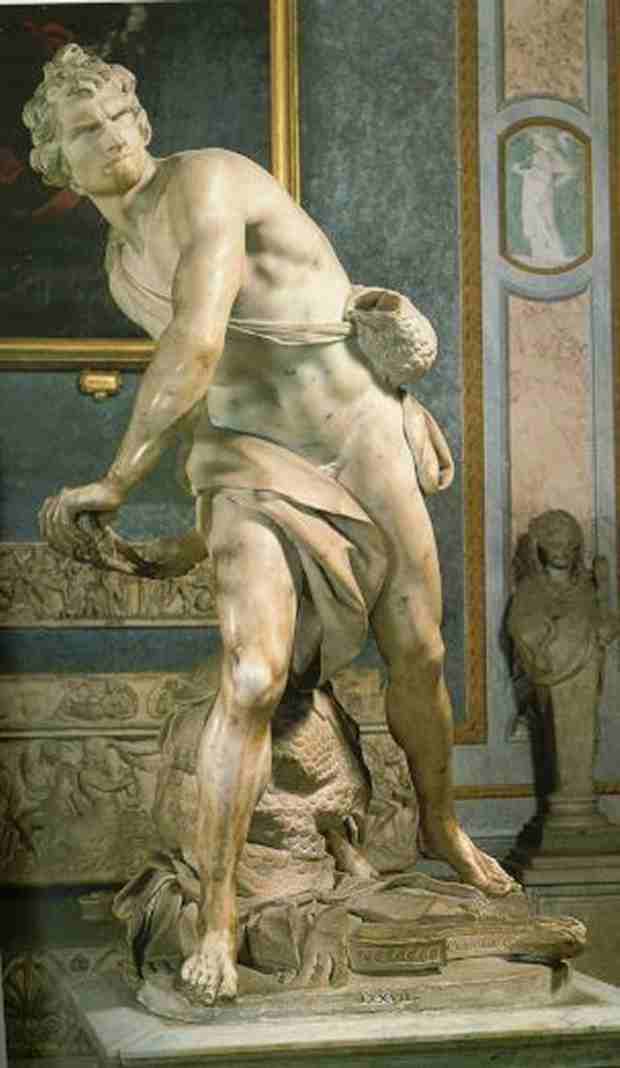

Slide 14: Bernini, David (Villa Borghese)

Slide 15: Bernini, Habbakuk (S.M. del Popolo, Chigi Chapel)(image not found)

Slide 16: Bernini, Apollo & Daphne (Villa Borghese)

Slide 17: Bernini, A & D (Borghese), det., head of Apollo

Slide 18: Bernini, A & D (Borghese), det., Daphne(image not found)

Slide 19: Bernini, St Longinus (St Peter’s)

Slide 20: Bernini, St Longinus (St Peter’s), det. head(image not found)

Slide 21: Hellenistic, Laocoon (Vatican)

Slide 22: Rome, St Peter’s, apse, general(image not found)

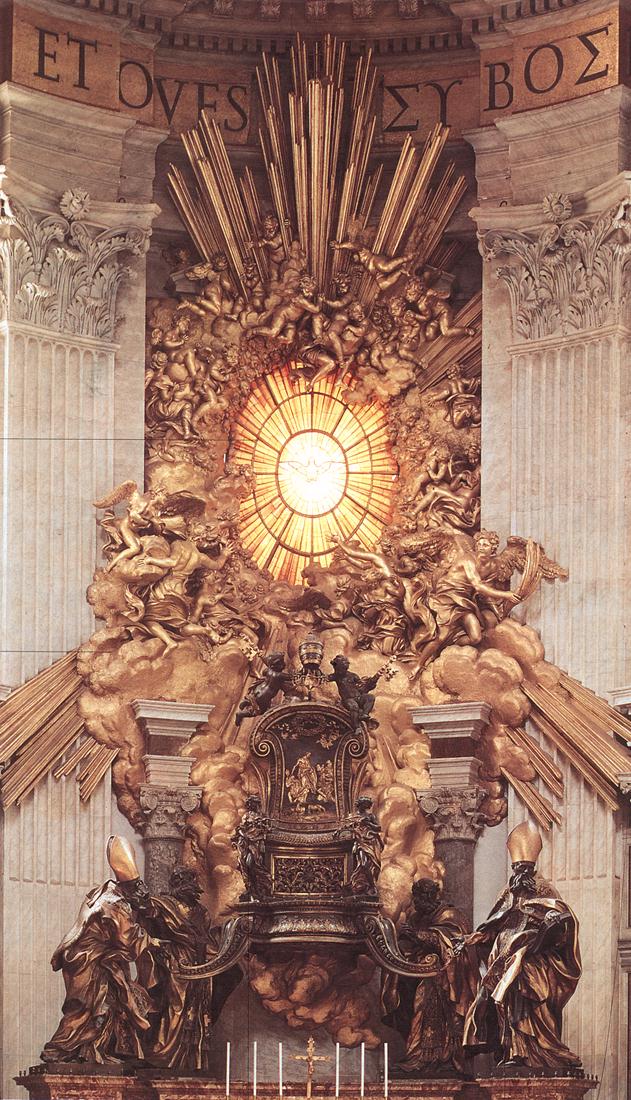

Slide 23: Bernini, Catedra Petri (St Peter’s)

Saint Peter’s throne is the last of Bernini’s large monuments designed for the San Pietro. This completes and crowns his forty years long work in the decoration of the interior of the main church of the Roman Catholics. The throne symbolizes the power of the Pope. Bernini created an optical and artistic unity of the throne and the baldachin erected above the tomb of Saint Peter. The light coming from a natural source (the window of the apsis) is part of the composition, similarly than in two other great Bernini compositions, in the Saint Therese group, and in the tomb Ludovica Albertoni.

Slide 24: Bernini, Catedra, det., SS Ambrose + Athanasius(image not found)

Slide 25: Bernini, Catedra, det., SS Ambrose + Ath, det.(image not found)

Slide 26: P. da Cortona, Divine Providence, det., Hercules

Slide 27: P. da Cortona, Rape of the Sabines (Capitoline)

Slide 28: Bernini, Pluto & Persephone (Borghese)

The large marble group of Pluto and Proserpina by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, shows Pluto, powerful god of the underworld, abducting Proserpina, daughter of Ceres. By interceding with Jupiter, her mother obtains permission for her daughter to return to earth for half the year and then spend the other half in Hades. Thus every spring the earth welcomes her with a carpet of flowers. The group was executed between 1621 and 1622. Cardinal Scipione gave it to Cardinal Ludovisi in 1622, and it remained in his villa until 1908, when it was purchased by the Italian state and returned to the Borghese Collection. In this group Bernini develops the twisting pose reminiscent of Mannerism, combined with an impression of vital energy (in pushing against Pluto’s face Proserpina’s hand creases his skin and his fingers sink into the flesh of his victim). Seen from the left, the group shows Pluto taking a fast and powerful stride and grasping Proserpina, from the front he appears triumphantly bearing his trophy in his arms; from the right one sees Proserpina’s tears as she prays to heaven, the wind blowing her hair, as the guardian of Hades, the three-headed dog, barks. Various moments of the story are thus summed up in a single sculpture.

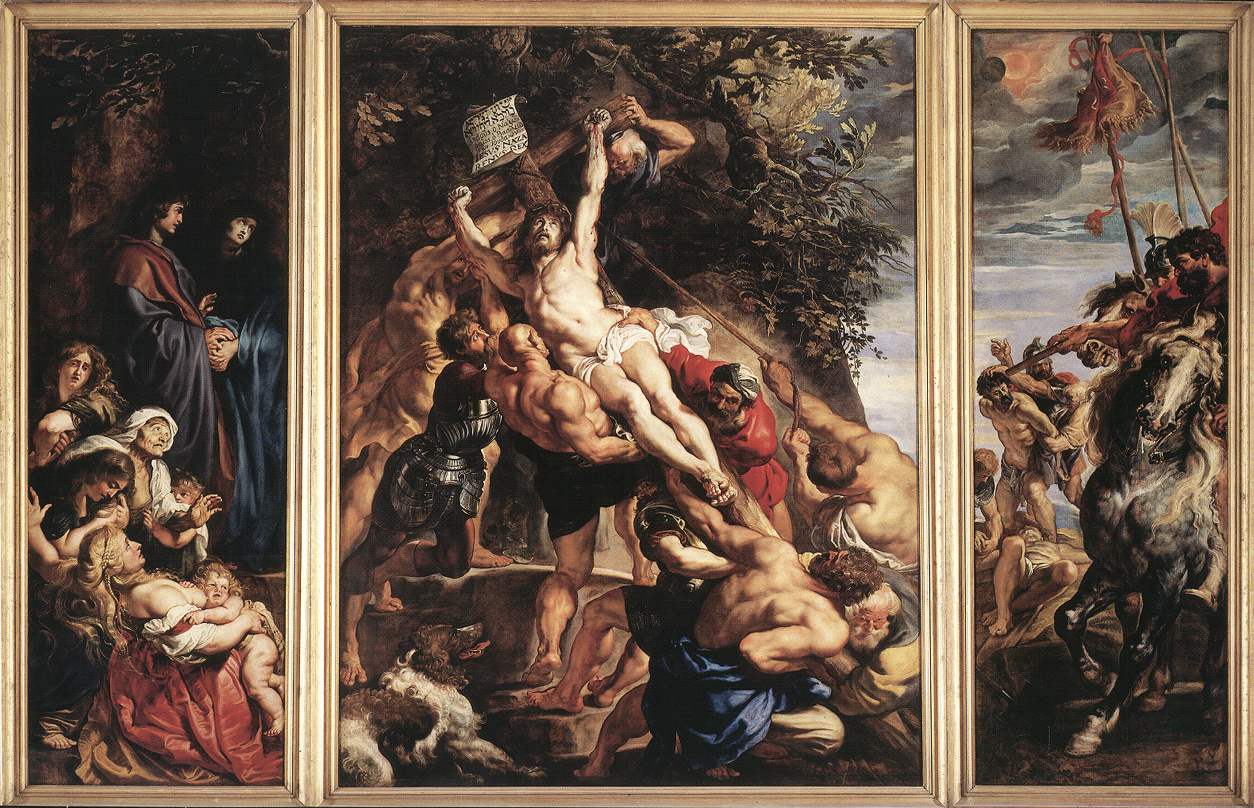

Slide 29: Rubens, Raising of the Cross (Antwerp Cathedral)

Slide 30: Rubens, Descent from the Cross (Antwerp Cathedral)

Slide 31: Rubens, Assumption of Virgin (Hamburg)

As recounted in the New Testament’s Apocrypha, Jesus’ mother Mary was physically raised, or assumed, to heaven after her death. In this Assumption of the Virgin, a choir of angels lifts Mary’s body upward in a dramatic spiraling motion toward a burst of divine light. The twelve apostles gather around her tomb. Some raise their hands in awe; others reach down to touch her discarded shroud. The three holy women are probably Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary’s two sisters. The kneeling woman holds a flower, referring to the blossoms that miraculously filled the empty coffin. In 1611, the cathedral at Antwerp announced a competition for an Assumption altar. On 16 February 1618, Rubens submitted two modelli or models to the clergy. He finished the huge altarpiece in September 1626. Thus, fifteen years elapsed between the beginning and conclusion of this project. The cathedral needed the time to complete a majestic marble frame, and Rubens was preoccupied with other commissions.

Slide 32: Rubens, Samson and Delilah (London, NG)

Slide 33: Rembrandt Blinding of Samson (Frankfurt)

The story of Samson, which had a great attraction for the Baroque public, is prominent in Rembrandt’s production during the thirties. He painted Samson Threatening his Father-in-Law (1635, Staatliche Museen, Berlin) and the Marriage of Samson (1638, Gemeldegalerie, Dresden). His Blinding of Samson more than any other work shows Rembrandt’s unrivalled use of the High Baroque style to appeal to his contemporaries’ interest in the sensational. It is his most gruesome and violent work. The painting represents the bloody climax of the story. Samson has been overwhelmed by one of the Philistines, who has the biblical hero locked in his grip. Samson’s right hand is being fettered by another soldier, and a third is plunging a sword into his eye, from which blood rushes forth. His whole frame writhes convulsively with sudden pain. The warrior standing in front, silhouetted against the light in the Honthorst manner, has his halberd ready to plunge into Samson if he manages to free himself before the hideous deed is done. Delilah, with a look of terror mixed with triumph, is a masterful characterization seen in a half haze, as she rushes to the opening of the tent. Here again the chiaroscuro adds an element of mystery and pictorial, as well as spiritual, excitement. The whole scale of light, from the deepest shadows to the intense bright light pouring into the tent, has gained in power and gradations over the works of the Leiden period. The scene could not have been represented with more dreadful accents, and Rembrandt may have finished it with the triumphant feeling of having surpassed Rubens’s dramatic effects, for this picture was also inspired by a work of the Flemish master: The Capture of Samson (now in Munich). This large painting originally was even larger. Several copies are also known.

FACIAL EXPRESSION

Slide 34: Caravaggio, Boy bitten by Lizard (Florence, Longhi)

Slide 35: Bernini, Apollo & Daphne, det., head of Daphne(image not found)

Slide 36: Rembrandt, Self-portrait ‘open-mouthed’ (etching)

Slide 37: Bernini, David, det. head(image not found)

Slide 38: C. le Brun, ‘expression of Terror’. drawing(image not found)

RELIGIOUS EXPRESSION

Slide 39: Bernini, Sta Bibiana (S. Bibiana)

Slide 40: Bernini, Sta Bibiana, det., head(image not found)

Slide 41: Bernini, St Mary Magdalene (Siena Cath., Chigi Ch)

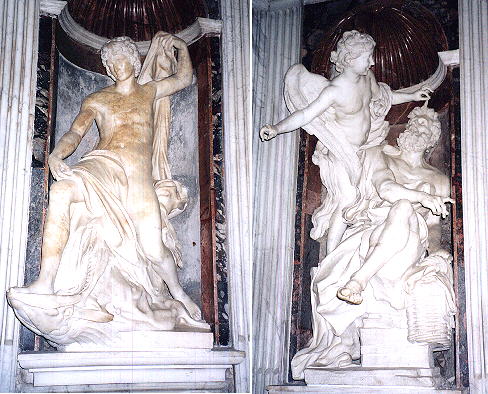

Slide 42: Rome, S, Maria del Popolo, Chigi Chapel, general

Slide 43: Bernini, Daniel (S. Maria del Popolo, Chigi Chapel)(image not found)

Slide 44: Bernini, Angel+ Crown of Thorns (S.A. delle Fratte)

Slide 45: Bernini, Angel+Superscription (S.A. delle Fratte)(image not found)

Slide 46: Bernini (after), A+C of Thorns (Ponte S. Angelo)(image not found)

Slide 47: Bernini, Ecstasy of St Theresa (Cornaro Chapel)(image not found)

Slide 48: Lanfranco, Ecstasy of St Marg. of Cortoiza (Naples)

Slide 49: P. da Cortona, Virgin appears to St Francis (Vatican)

Slide 50: Baciccio, Death of St Francis Xavier (S. Andrea)(image not found)

Slide 51: Rome, S. Maria della Vittoria, Cornaro Chapel

The centerpiece is The Ecstasy of S. Teresa di Avila, a large statue (height 3.5m) designed to be illuminated by reflected light from a hidden window. The statue depicts a remarkable mystic experience related by S. Teresa herself: Beside me on the left appeared an angel in bodily form… He was not tall but short, and very beautiful; and his face was so aflame that he appeared to be one of the highest ranks of angels, who seem to be all on fire… In his hands I saw a great golden spear, and at the iron tip there appeared to be a point of fire. This he plunged into my heart several times so that it penetrated my entrails. When he pulled it out I felt that he took them with it, and left me utterly consumed by the great love of God. The pain was so severe that it made me utter several moans. The sweetness caused by this intense pain is so extreme that one can not possibly wish it to cease, nor is one’s soul content with anything but God. This is not a physical but a spiritual pain, though the body has some share in it — even a considerable share. The figures of S. Teresa and the angel are seen upon a stage, witnessed by Cardinals and Doges of the Cornaro family looking on from flanking balconies.

Slide 52: Rome, S. Maria della Vittoria, Cornaro Chapel, plan

Slide 53: Bernini, Cornaro family members (Cornaro Ch)(image not found)

Slide 54: Bernini, Ecstasy of St Theresa, group, det.

Slide 55: Bernini, Ecstasy of St Theresa, group, det. 2

Slide 56: Bernini, Ecstasy of St Theresa, det., head of Theresa(image not found)

Slide 57: Bernini, Ecstasy of St Theresa, det., head of angel(image not found)

PORTRAITURE

Slide 58: Bernini, Costanza Buonarelli (Florence, Bargello)

Slide 59: Bernini, Pope Paul V (Vatican)

Slide 60: Bernini, Scipione Borghese (Villa Borghese)(image not found)

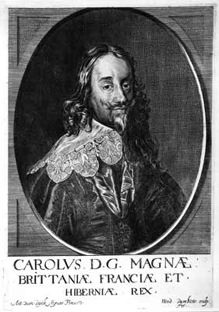

Slide 61: Bernini (after), Charles I (engraving)

Slide 62: A. van Dyck, Charles 1: 3 views (Royal Coil)

Slide 63: Bernini, Pope Urban VIII(Vatican)

Slide 64: A. van Dyck, Cornelius v.d. Geest (London, NG)

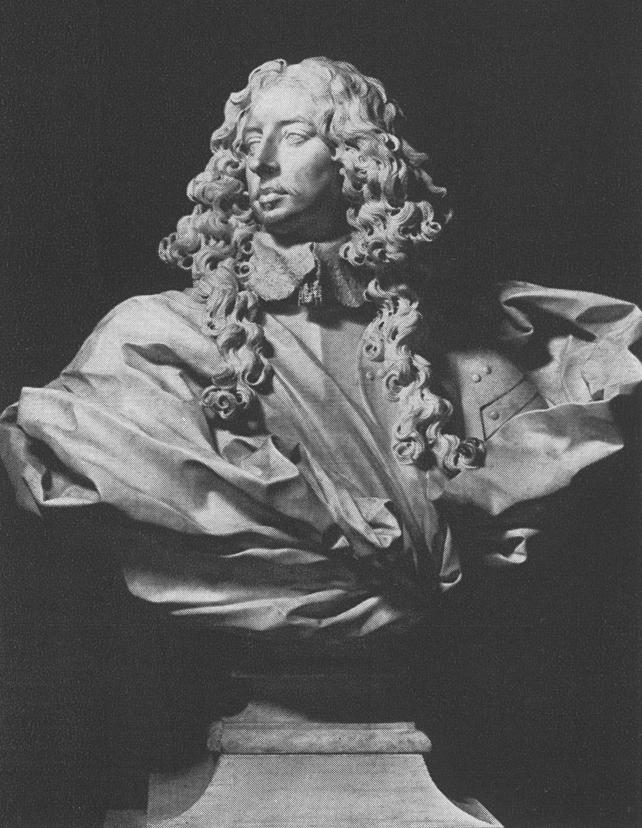

Slide 65: Bernini, Francesco d’Este (Modena)

Slide 66: Bernini, Louis XIV (Versailles)

Bernini had originally designed the site (a mountain peak) for the Equestrian Statue of Louis XIV, the Sun King, on a fiery steed, as can be seen from the preliminary sketch. The base supporting it today lacks the vertical thrust that would enhance the image of this absolute monarch. However, Bernini chose to make the features of Louis XIV resemble those of Alexander the Great. The original terracotta model is by Bernini himself, though the sculpture was executed by his pupils, since he was by then over seventy-three years old. However, the work did not meet with a favourable reception in Paris and Girardon transformed the group into a statue of Marcus Curtius, which was formerly transferred to Versailles and is now in the Louvre.