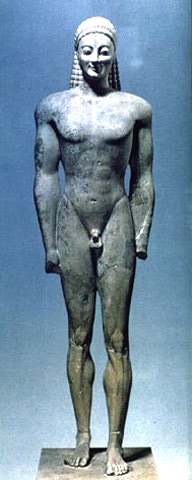

Slide 1: Kouros from Volomandra

FUNERARY KOUROS OF VOLOMANDRA Mid-6th century B.C. National Archaeological Museum, Athens During the mid-sixth century the figure is erect, poised, and yet immobile, an image of energy at rest. One leg stands slightly in front of the other. The arms are attached to the body. The kouros often stood in a sanctuary or marked a grave. Like the Stele of Aristion it lacks motion.

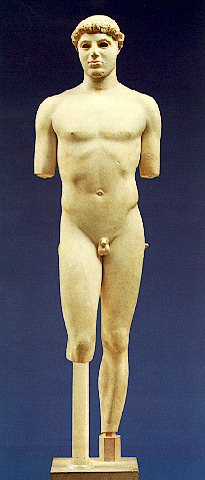

Slide 2: Kouros (Aristodikos)

By about 500 BC E, the kouros has moved into the transition between late archaic and severe style. Aristodikos sports the short hair, the unsmiling face and the long, athletic proportions current at a stage in Greek scsculptures it is about to discover contrapposto and the physics of the figure moving naturally in space.

Slide 3: Kritios boy

Kritios Boy c. 480 B.C. Acropolis, Athens Under life size, marble

Slide 4: Kore (including Euthydikos)

Style: Late Archaic, ca. 490 B.C. – 480 B.C. Period: Late Archaic, votive Class: Free-standing statue: kore, Athens, Acropolis Region: Attica, found at Athens, Acropolis, found east of Parthenon in 1882. Marble, possibly Parian marble,height. 0.589 m

Dedicatory statue of maiden, late example of kore type. Frontal pose, characteristic archaic gesture of skirt pulled to side, here with left hand. Left leg forward. Right arm originally extended in offering. Coiffure relatively simple with emphatic central part, three long tresses fall forward over each shoulder. Ionic style of dress with himation over thin chiton, but again simply rendered. Detailed decoration added in paint, as the frieze of racing chariots on the chiton.

Generally considered to be part of the debris from the Persian destruction of 480.

Form and Style:

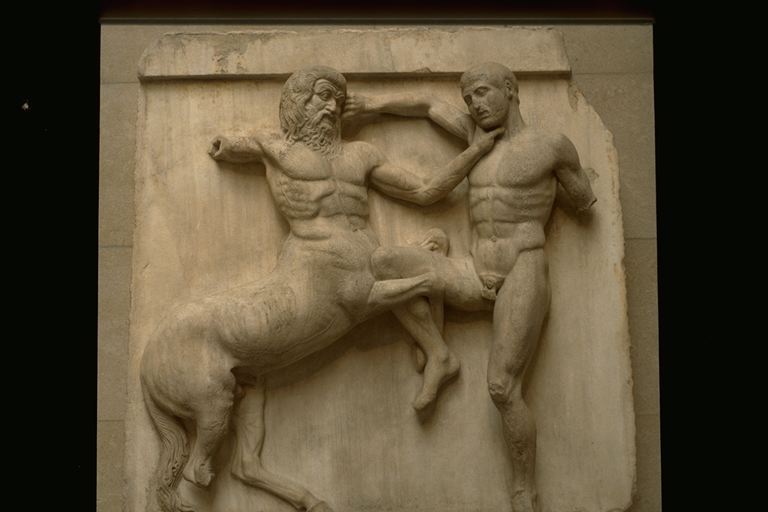

Stance and Alexander Sarcophagus

Those are pictures of Alexander’s Sarcophagus displayed now at Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Ahhh, don’t think my mind is wandering. It is not, obviously, Alexander ‘s remains resting there (his tomb has never been found)… This great marble sarcophagus is called the Alexander Sarcophagus because the king is actually represented in the battle scenes we can see along the sides. Dating from the late 4thC, the sarcophagus is regarded as a remarkable work of art, and its carved friezes are admired as being among the most exquisite and delicate examples of Hellenistic art.

This piece was discovered in 1887 by Turkish archaeologist Osman Hamdi Bey in a royal necropolis at Sidon in Lebanon. From there this and other sarcophagi were carried by ship to Istanbul.

The hunting scene on the sarcophagus in which Greeks and Persians are shown hunting together is a symbol of the way in which Greeks and Persians were eventually united under Macedonian rule.

Slide 6: Aegina – pedimental sculpture

Located on a pine – clad hill and commands a splendid view of the Saronic Gulf — Bay of Ayia Marina, erected 510-490 B.C.

On site of two earlier temples. Geometric period structure — perhaps apsidal. Archaic temple, tetrastyle in antis, shallow porches, cella, exterior triglyphs — blue, interior triglyphs — black, f. Altar in front of East side

Has been called the most perfectly developed of the late Archaic temples in European Hellas

The sanctuary may have been site of continuous religious activity from at least Mycenaean times. The deity — Aphia (Aphaea). Seem to have been a variant of a Mother Goddess from Crete, Britomartis. Daughter of Zeus and Carme. Devoted to hunt — a favorite of Artemis, In order to escape from the attentions of Minos, who had fallen in love with her, she cast herself into the sea and was caught up in the nets of some fishermen. When one of the fishermen became enamoured of the beautiful girl, she once more plunged into the sea; this time she emerged at Aegina, where she was rendered invisible in a grove. — Aphaea concealed herself in a cave, which is actually situated in the NE corner of the peribolus of the Archaic sanctuary.

Slide 7: Olympia – metopes and pediments(image not found)

Slide 8: Poseidon/Zeus (National Museum, Athens)

The magnificent bronze statue of Poseidon or Zeus of Artemission (460-450 BC) is one of the favorites. Found some sixty – five years ago off the Evian coast, this beautiful work is awe – inspiring and shows majesty in both posture and expression.

Also see Marathon boy

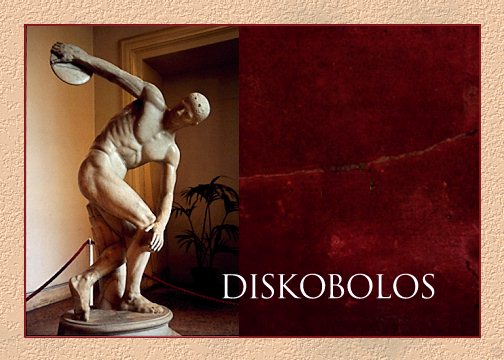

Slide 9: Discobolos (Myron)

Myron, who almost captured the souls of men and animals in his bronzes… Petronius, Satyricon

Although Myron was known in antiquity for a bronze heifer so realistic that it could be mistaken for an actual cow, it is the Discus Thrower for which he is most famous. A Roman copy of a mid – fifth century BC bronze, it exemplifies the Greek sense of harmony and balance (rhythmos) which Pliny praises.

” Myron is the first sculptor who appears to have enlarged the scope of realism, having more rhythms (rhythmos) in his art than Polycleitus and being more careful in his proportions (symmetria). Yet he himself so far as surface configuration goes attained great finish, but he does not seem to have given expression to the feelings of the mind, and moreover he has not treated the hair and the pubes with any more accuracy than had been achieved by the rude work of olden days.”

Symmetria is the commensurability of parts, all in balanced and harmonious proportion, which is so well exemplified in the Discobolus. The athlete is in equilibrium, posed just before releasing the discus, the parts of his body in dynamic counterbalance. The head, however, seems almost to be a separate bust, so passive is its expression.

In his Institutio Oratoria (Training of an Orator), Quintilian, who wrote in the first century AD, compares the rhetorician and the artist, and the distinguishing personal style that makes each unique. Interestingly, his scheme of the evolution of sculpture is different from that of Pliny….

Slide 10: Bronze figures from Riace

Slide 11: Athena and Marsyas (Myron)

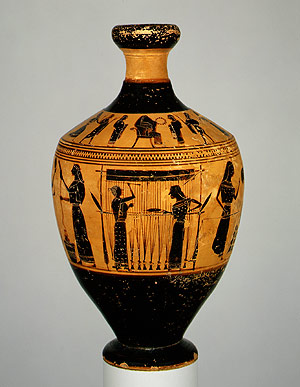

Slide 12: Vase painters: Amasis painter, Exekias, Berlin painter and Niobid painter

Slide 13: Parthenon – metopes, frieze and pediments

Slide 14: Doryphoros & Diadoumenos (Polyclitus)

Slide 15: Bronze Hermes from Marathon

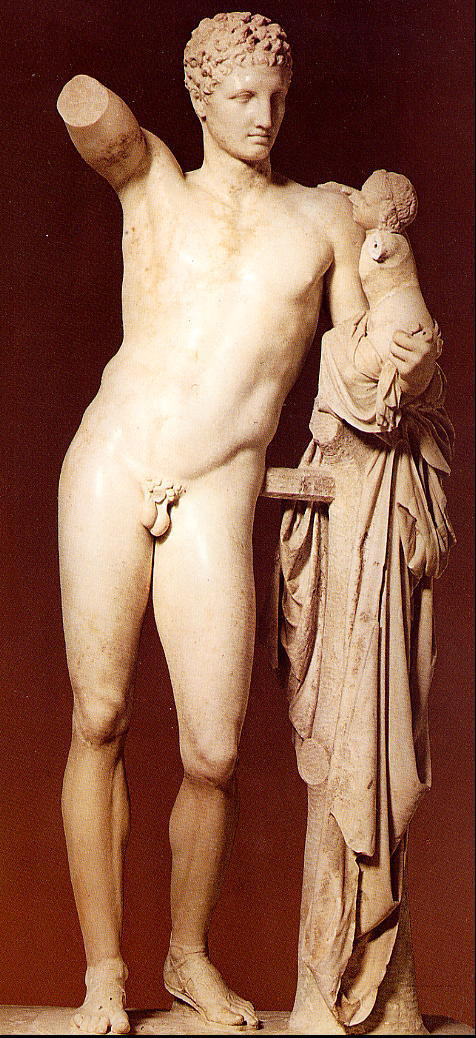

Slide 16: Hermes from Olympia (Praxiteles?)

Slide 17: Venus from Cnidos (after Praxiteles)

Slide 18: Crouching Venus

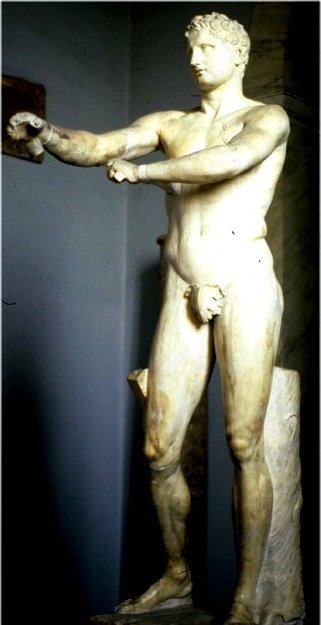

Slide 19: Agias (Lysippos)

Slide 20: Apoxyornenos (Lysippos)

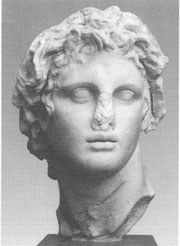

Slide 21: Portrait of Alexander (after Lysippos?)

Slide 22: Portrait of a philosopher

Slide 23: Sarcophagus of Mourning Women

Slide 24: Pergamon, victory monument of Attalus I

Slide 25: Pergamon, Great Altar of Zeus

Slide 26: Laocoön

One of the major discoveries of the Italian Renaissance, this sculptural grouping was found in Rome in 1506 in the ruins of Titus’ palace. It depicts an event in Vergil’s Aeneid (Book 2). The Trojan priest Laocoön was strangled by sea snakes, sent by the gods who favored the Greeks, while he was sacrificing at the altar of Neptune. Because Laocoön had tried to warn the Trojan citizens of the danger of bringing in the wooden horse, he incurred the wrath of the gods. The grouping was probably designed for a frontal view only.

The theatricality and emphasis on emotional intensity is typically Hellenistic Greek–often called Baroque as well. Note the writhing serpents, one of whom bites Laocoön ‘s left leg, and pained expressions.

The furrowed brow and open – mouthed pain would be copied by Bernini and Caravaggio in the seventeenth century.