English Decorated and Perpendicular

Slide 1: Exeter Cathedral

Exeter Cathedral

Decorated Gothic (1275-1375) – aka Geometric, Curvilinear, and Flamboyant

The church here was begun in the 11th century, but most of what remains is the result of rebuilding between 1275-1375. The Lady chapel and retrochoir were added at this time, to be followed by the presbytery and the choir. The nave was built in the mid 14th century, under the direction of Richard Farleigh, who was also responsible for the spire at Salisbury. The vaulting extends for an extraordinary 300 feet, making it the longest uninterrupted stone vault in Britain. The carving is wonderful, particularly in the Minstrel’s gallery (look for the 14 angels, each carrying a different musical instrument)and the pulpitum.

Slide 2: Bristol Cathedral (choir and Lady chapel)

The eastern end of the Cathedral, especially the Choir, gives Bristol Cathedral a unique place in the development of British and European architecture. The Nave, Choir and Aisles are all of the same height, making a large hall. Bristol Cathedral is the major example of a ‘hall church’ in Great Britain and one of the finest anywhere in the world.

Slide 3: Ely Cathedral (choir and Lady Chapel)

Slide 4: Bristol, St Mary Redcliffe

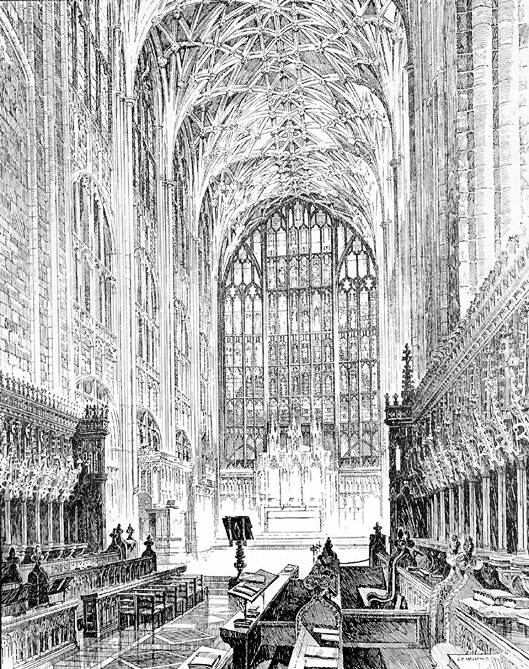

Slide 5: Gloucester Cathedral (choir, transepts and cloister)

Slide 6: Gloucester Cathedral nave

Slide 7: Tewkesbury Abbey

Gothic Facades

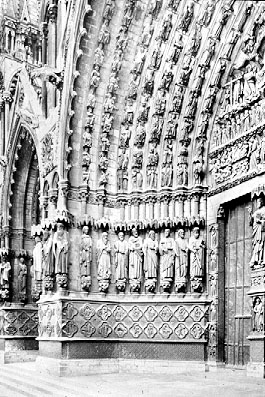

Slide 8: Paris, Notre Dame

Slide 9: Reims Cathedral

Slide 10: Wells Cathedral

Slide 11: Peterborough Cathedral

Decoration and furnishings

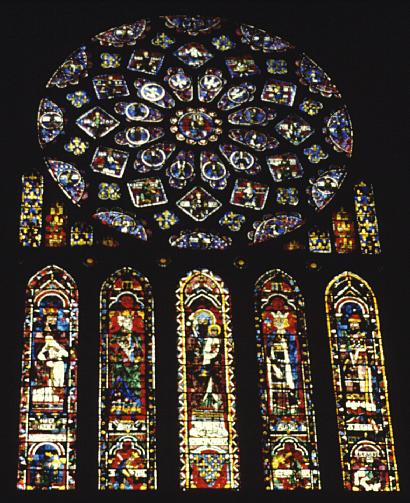

Slide 12: Chartres Cathedral, stained glass

Slide 13: Amiens Cathedral, west portal

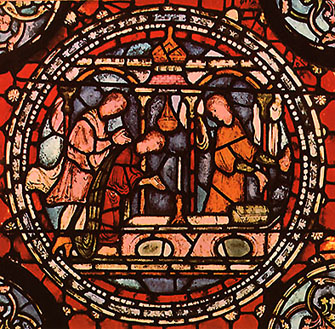

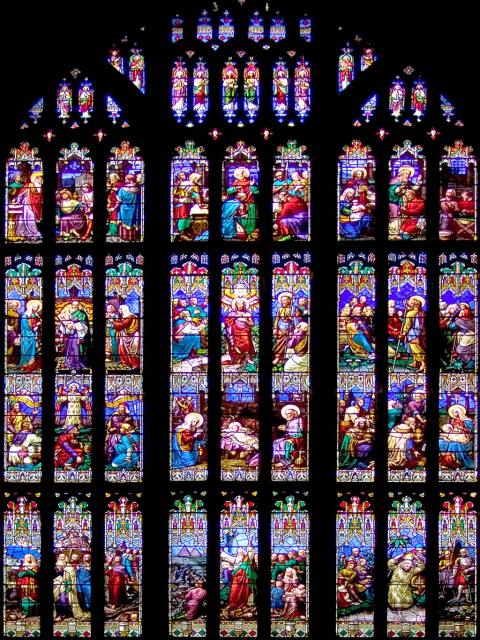

Slide 14: Canterbury Cathedral, stained glass

From the Corona, this 13th-century glass shows pilgrims praying at the old shrine of St. Thomas in the crypt, before his relics were translated to the much more opulent shrine in the Trinity Chapel (1220).

Two events occurring in 1170 and 1174 laid the foundations of what today is regarded as one of the most important stained glass collections of the late 12th century in the world. The murder of Thomas Becket, as despicable as it was, provided the Cathedral with a powerful attraction to pilgrims, who came to Canterbury in enormous numbers to make offerings. When disaster struck again with the destruction by fire of the Romanesque Quire in September 1174, it was the proceeds from this lucrative pilgrim trade that enabled the monks to build the new Quire and the Trinity Chapel and to fill it with stained glass of outstanding splendour.

The fact that, unusually, the Canterbury monks did have a steady income at their disposal resulted in the creation of a building of unprecedented scale and complexity which was completed in a remarkably short period of time. The glazing scheme was conceived in close co-operation between the master builder, glazier and the monks. By 1176, the complete programme was determined and brought to life within 44 years by workshops of English and French craftsmen. The scheme is thus unusually homogenous in its planning and execution, reflecting also its close integration in the overall concept of the eastern arm of the church which was to serve two distinct categories of worshipper, the monks and the pilgrims.

The medieval Cathedral was part of a priory, and in the body of the Quire the monks observed the daily routine of the monastic office. The windows of this part are therefore of a very different character from those in the Trinity Chapel which served the pilgrims for their devotions at St. Thomas’ shrine. Besides numerous windows in side chapels, the glazing scheme for this reason consists of three major series, one for the Quire and one for the Trinity Chapel respectively, and the third on clerestory level linking both parts of the building together again.

In the Quire aisles, a biblical emphasis prevailed. Here the mediaeval monks could study the twelve windows from both Old and New Testaments, arranged to demonstrate the way in which events of the Old Testament were thought to prefigure events in the New. This typological interpretation is based on one of the most popular mediaeval books, the Biblia Pauperum or ‘Poor Man’s Bible’. The two surviving windows of this series in the north Quire aisle give a striking insight in the mediaeval way of interpreting the world. For the pilgrims visiting St. Thomas’ shrine, a different subject matter was requested….

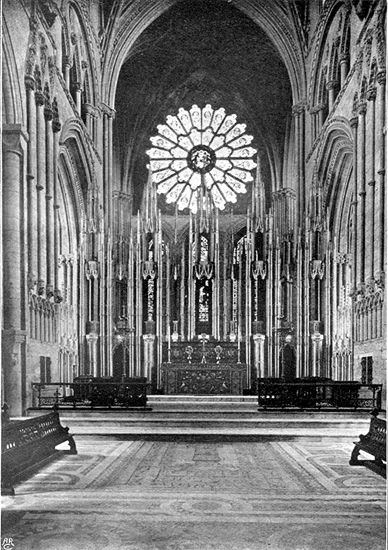

Slide 15: Gloucester Cathedral, west window

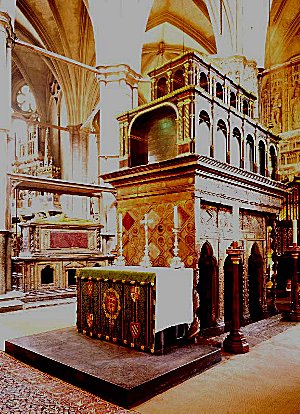

Slide 16: Exeter Cathedral, bishop’s throne

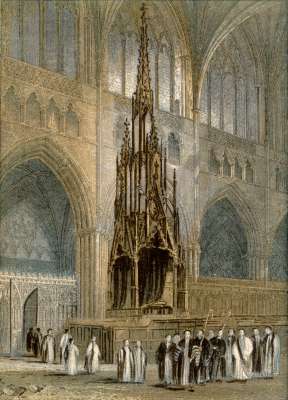

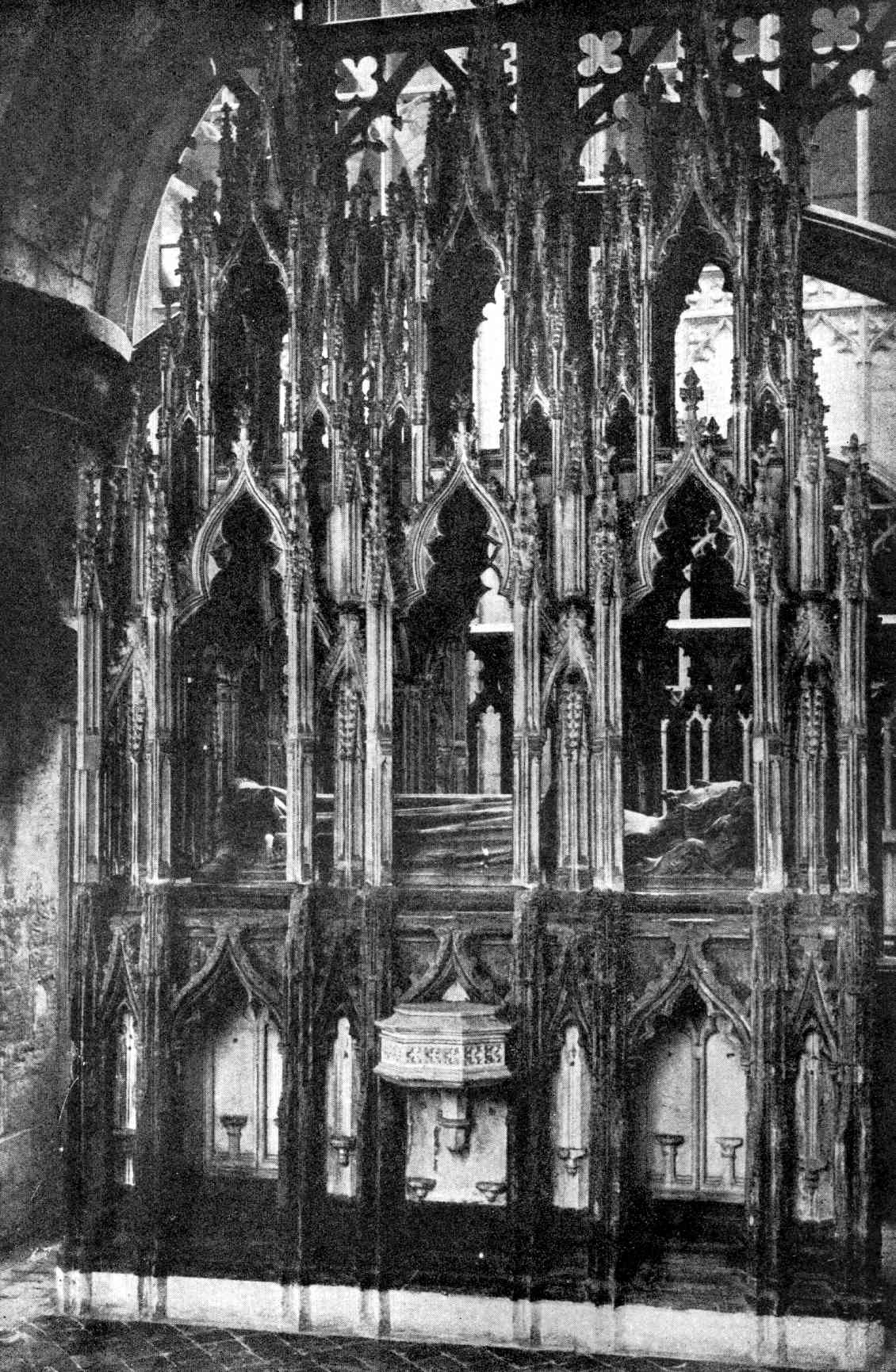

Slide 17: Durham Cathedral, choir screen

Uses and topography

Slide 18: Bristol, St Mary Redcliffe (north porch)

Slide 19: Chartres Cathedral, south transept

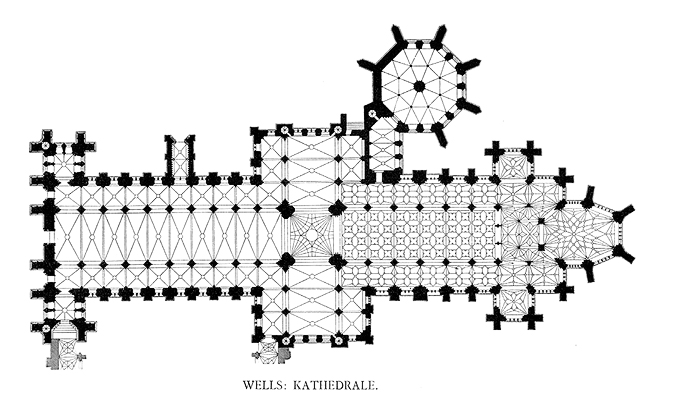

Slide 20: Wells Cathedral, ground plan

Slide 21: Ely Cathedral, ground plan (Romanesque and Gothic)

Slide 22: Westminster Abbey, shrine area

Slide 23: Roger van der Weyden, The Seven Sacraments (Antwerp)

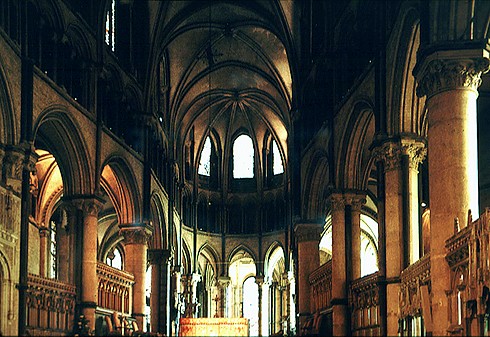

Slide 24: Canterbury Cathedral, Trinity Chapel

Slide 25: Gloucester Cathedral, Edward II tomb

Slide 26: Duccio, Maesta (Siena)

Slide 27: Westminster Retable

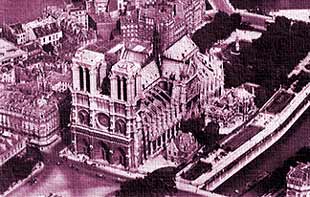

Slide 28: Paris, Notre Dame, aerial view

Slide 29: Florence, Duomo, aerial view

Slide 30: Wells, Cathedral close