One sentence summary: Hardwick Hall is a vertically-orientated massing structure with a central hall and external loggia that combines classical and medieval elements and was built in the 1590s by Elizabeth Shrewsbury and designed by Robert Smythson who also designed Longleat and Wollaton.

Hardwick Hall is one of the most amazing survivals from the Tudor period that has had only minor internal alterations and which still contains many of its original fixture sand fittings.

Bess of Hardwick married four times, each time rising in status and wealth. After her death Hardwick Hall was considered old-fashioned and was not used by her heirs who poured all their attention to Chatsworth, which as a result now has its Tudor origins obscured by later Baroque modifications. In the sixteenth century marriage was the only way a woman could advance herself and Bess of Hardwick did so through force of character rather than beauty. She was also very interested in buildings and took a major part in the design.

Her husband, the Earl of Shrewsbury, was the richest man in the country and when he died in 1590 Bess became the second richest woman, second only to the Queen. Bess had a very strong personality and she and the Earl violently argued in public, screaming abuse at each other, the the done thing in the sixteenth century. Elizabeth had to intervene and Bess and the Earl were estranged for the rest of their marriage. Bess lived in her old family home in the small manor of Hardwick and between 1587 and 1590 she improved the old home which can today be seen as a ruin alongside Hardwick Hall. In her time the old building was actively used, perhaps to provide extra space for guests and in case of a visit by Elizabeth.

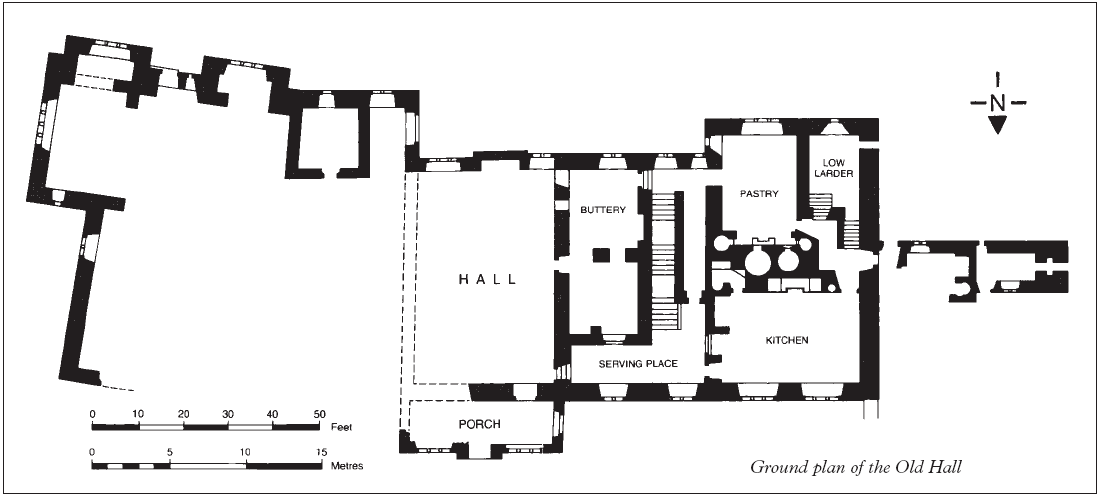

The Old Hall is now a ruin to the right of the new building.

The local schoolchildren have a saying that may date from the Tudor period, that Hardwick is “more glass than wall”. It is symmetrical with a loggia or colonnade and strapwork. There are six vertical turrets each with three “ES” monograms with a coronet above to show she was a countess, 18 in total. The building is on a hill and can be seen from the M1. It has similarities with Longleat but its vertical stress marks it out.

The colonnade is like that inside the inner court at the Royal Exchange and the internal arcade at Burghley, but this one is external. The back show above is the same as the front. It has classical string courses and a balustrade but it is plain compared with Wollaton Hall. There are enough medieval elements to make it uncertain whether it is a medieval revival in the late Elizabethan period or a continuation of the classical development.

The designer Robert Smythson also worked on Longleat and Wollaton.

Note that like Longleat the towers at Hardwick miss the corners and the heavy massing gives a strong feeling of dynamism.

‘Compact houses’ like Hardwick and Wimbledon can be compared with the older style courtyard houses. Wimbledon was built by Lord Burghley’s son in 1588. A 17th century print of Wimbledon House shows it was also unadorned, very tall with dramatic massing. The route up to the house via a series of steps was original and the source could have been the Villa Farnese, Caprarola, c. 1550.

On approaching the building, what would have impressed a Tudor visitor? First the size and the extensive use of very expensive glass. Second the heraldry, the initials and the coronet above the house and finally the whole house can be seen as a device consisting of two Greek crosses joined together. Another example of a Greek cross is Sir Thomas Tresham’s Lyvden new Bield

Sir Thomas Tresham, Lyvden New Bield, 1595-1605

The high windows on the second floor of Hardwick show the high status of the occupants. The ground floor windows are the kitchen windows and the kitchens are sunken and the windows are set high on the kitchen walls. Bess of Hardwick lived on the first floor and the second floor were state rooms for Elizabeth, although she never visited.

Wollaton was also designed by Smythson but it si much more ornamental, Hardwick is restrained and at times looks almost modern. One of the Hardwick towers was for banqueting unlike Montacute where there are two two-storey banqueting pavilions in front of the house.

Hardwick as a wall either side of the front of the house forming a courtyard outside the building. There is a formal gatehouse entrance leading through the wall into the courtyard.

The hall in Hardwick is central to keep the building symmetrical although Hardwick was not the first to have a central hall with the screens passage inside the front door and opening directly into the hall. The Hardwick Old Hall had a similar design. There are classical stone columns between the screens passage and the hall and the hall is tall but small, continuing the process of marginalizing the hall until it becomes simply a foyer.

There is a long processional route to the second floor scan which can be seen on the left. It is a very clever use of space by Smythson, you cannot see to the end of the route as it curves round but the windows throw light on the upper stairs in a theatrical way. The Great Chamber is breathtaking, enormously high at the top of the staircase and designed for entertaining the monarch. There are many smaller parlour for ordinary eating.

The tapestries were commissioned in 1587 from Brussels and the fit so well that it is possible the room was built to house the tapestries. The top of the walls are highly painted plaster bas relief in bright colours. The scene is Diana in the forest and although the scene is copied from Netherlandish prints there are additions such as roebucks (Bess of Hardwick’s emblem) chasing wild beasts from the forest, perhaps showing her loyalty to the monarch. There are brightly painted prints on the walls and a famous table inlaid with marquetry chess set, card table and so on.

The inventory below was taken in 1601 by a servant stock taking and it is an invaluable guide to the furnishings and furniture of the period. There is a copy of the full inventory in the Warburg Library.

The Great Hall paintings must have been stacked in the window bays as there is no where else to hang them in the room.

The fireplace has the Royal coat of arms, perhaps in anticipation of a visit by Elizabeth, but perhaps because her granddaughter Arabella Stuart had a claim to the throne and as she was young, if she had become queen Bess could have been Regent.

Food would be served in the Great Hall as part of an elaborate ceremony that involved the Lord Steward heading a long procession of servants carrying the covered food up the processional route to the High Great Chamber.

Beyond the High Great Chamber were a sequence of increasingly private rooms – first the Withdrawing Chamber, then the Best Bed Chamber and the Pearl Bed Chamber.

We have an inventory of the Withdrawing Chamber (see below) that includes portraits such as Mary Queen of Scots and biblical works such as the Prodigal Son and classical works such as Ulysses and Penelope. We believe that such inventories were written in sequence as the person preparing them walked around the room but they tell us little about the exact placement. As the walls were covered in tapestries it is likely that paintings were relegated to the window surrounds.

The panel painting of ‘The Return of Ulysses to Penelope’ (anon, 1570) survives at Hardwick Hall and is clearly copied from two Netherlandish engravings, one was copied for the knight (Bible woodcut, 1564, The Triumph of Mordici) and the other for the building structure (the same bible, Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream). This copying was a common practise, for example, in the Processional portrait of Elizabeth the building in the background is from a foreign print. A book by Wells-Cole called ‘The Art of Decoration in Elizabethan and Jacobean England: The Influence of Continental Prints, 1558-1625’ matches foreign prints with Tudor paintings. At Hardwick some prints were even stuck to the walls and painted over.

Mary Queen of Scots was put under the protection of Bess of Hardwick so she knew her well but at the time the inventory was taken Mary had been executed for high treason. It was also rumoured that Bess’s fourth husband George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury, who she married in 1568 (one of the premier aristocrats of the realm, with seven children from his first marriage; two of his children married two of hers in a double ceremony in February 1568) had had an affair with Mary Queen of Scots.

In the Best Bed Chamber (today called the Green Velvet Room) different types of embroidery were listed including an embroidered appliqué ‘Elizabeth and Mohammed’ with Elizabeth winning the competition.

In the Pearl Bed Chamber (today called the Blue Bedroom) there was an over mantel from the Book of Tobit or Tobias (regarded by Protestants as apocryphal) carved as an alabaster bas relief. It is believed it may have been brought by Bess from Chatsworth when she moved on her own to Hardwick. It is also copied from a Netherlandish print.

Long Gallery went the entire width of the house and was intended to impress with both its length and its height. Many of the paintings in the inventory still survive. The oldest Long Gallery is The Vine in Hampshire built in the 1520s although covered walkways were much older (Herstmonceux, c. 1440). They were originally used for exercise and for diplomatic conversation (e.g. Wolsey and Percy), and they provided security, so they were more relaxed than walking outside. They may have been used for teaching while walking and we know they did walk and talk about the portraits although they discussed the person portraited and any devices, not the artist. As they were upstairs they could also be used to show off the estate. We know courtiers tried to outdo each other with the length of their long galleries.

The Long Gallery tapestries (‘The Gideons’) were not commissioned by Bess, they were commissioned by Sir Christopher Hatton of Holdenby in Northants. He was a wealthy courtier of Queen Elizabeth who over stretched himself preparing for a possible royal visit to Holdenby and died in 1591 virtually bankrupt. His nephew was his executor and it was from him that Bess struck a deal to buy the Gideons at cut price, receiving a £5 discount because the Hatton coat of arms is woven into all the works. Bess then instructed her seamstress to patch the Hatton arms over with painted copies of her own arms. She then had the Hatton Hart, which is above the helm, furnished with antlers to make a Hardwick Stag. The helm and mantle above the escutcheon are male but could not be altered. It is possible that on purchase Bess supplied the measurements to Smythson who then applied these to his design so that the tapestries fitted perfectly between the fireplaces and on either side in the Long Gallery.

Many houses had collections of kings and queens although those earlier than the 16th century were painted from the artists imagination as we have no accurate portraits or no portraits. At the end of the Long Gallery there is a portrait of Elizabeth that has been attributed to Hilliard based on stylistic evidence alone.

In the Long Gallery inventory below there is ‘Our Ladie the Virgin Marie’ (now lost), which is surprising in a Protestant house. Was it related to the ‘Virgin Queen’ or Mary Queen of Scots? Did Bess inherit it, buy it or commission it? There are pictures of famous women in the house so it is possible it had no religious significance but was simply an historic portrait of a famous woman.

On the first floor is the Low Great Chamber (today called the dining room) and in the inventory below there is another picture of the Virgin Marie mentioned.

In the Little Dining Room (today called the Paved Room) there is a plaster overmantel of a naked woman with a cornucopia based on a print by Heinrich Goltzius of 1586.

The private chapel was originally two-stories high like Hampton Court but a ceiling has now been put in. See Chapel inventory below (a forme is a bench and an Angle is an Angel). There is a ‘Crucifixe’, an Annunciation and Three Kings. How can we explain these banned items in a Chapel? Bess was the same generation as the Queen as they were both born in the 1530s when such items were in every church and chapel. Although images were ‘banned’ in Henry’s reign the bann was not taken seriously until Edward’s reign and it was not until 1547/8 that all images in churches were destroyed. We know the Queen still had a crucifix in her chapel so Bess had the perfect excuse, if the Queen can do it so can I. We know that Bess was a loyal Protestant, not a secret Catholic as she was entrusted with acting as guardian of Mary Queen of Scots (1569-1584). Bess did try to take advantage of the situation when in 1574 she married her daughter Elizabeth to Charles Stuart, the brother of Lord Darnley, Mary’s second husband. She did this without permission of the Queen a potentially treasonable offence as the children would have a claim to the throne. Bess was summoned to London to answer the charge but she ignored the summons until the storm had blown over. In the event the couples daughter Arabella Stuart was wilful and spoilt and caused no end of problems for Bess.

Bess commissioned four paintings including the Conversion of Saul (to St. Paul on the road to Damascus). It includes Bess’s coat of arms and her initials ‘ES’. They are painted on cloth and are some of the handful of such paintings on cloth to survive. However, in the sixteenth century this was the most common type of painting as it was affordable yet looked like a much more expensive tapestry. B the end of the century even tradesmen could afford painted cloth. The cloth was canvas or linen and was stuck to the wall and never framed. As a result they rotted and that is why they have not survived.

For the full text of Lord Lumley’s 1590 inventory see L. Cust, ‘The Lumley Inventories’, The Walpole Society vo.6 (1918).

[This is a journal and a copy is available at the Warburg Library.]

HARDWICK HALL INVENTORY of 1601

Extracts from L. Boynton & P. Thornton, ‘The Hardwick Hall Inventory of 1601’ Furniture History vol. VIl (1971), pp.1-40.

Upper and Lower Chapel

‘In the upper Chapple: two peeces of hanginges imbrodered with pictures Seaven foote and a half deep..’

‘In the lowe Chapple: a Pulpitt, a Cubberd, fowre formes, a Crucifixe of imbrodered worke, too pictures of our Ladle the Virgin Marie and the three Kinges, the salutation of the Virgin Marie by the Angle.’

Low Great Chamber

‘In the lowe great Chamber: Eight peeces of tapestrie hanginges of the storie of David Eleven foote deep,..’

‘the picture of Queene Elizabeth, George, Erie of Shrouesbury, A glass with his and my ladies Armes in it, the Lord Burleigh, Lord Tresorer, the Ladle Margaret, Countess of Lenox, Charles Erie of Lenox, her sonne, The Ladle Arbella her grandChilde, My Ladies picture, Sir William Cavendishe, Mr William Cavendishe the elder, Mr William Cavendishe the younger, The Virgin Marie, Mr Thomas Cavendishe, father to Sir William Cavendishe…’

High Great Chamber

‘…the pictures of King Henry the Eight, Quene Elizabeth. Queene Marie, Edward the sixt, Duke Dolva, Charles the Emperor, Cardiani Woolsey, Cardinall Poole, Stephen Gardiner, Fowre pictures of the fowre partes of the woride…’

Withdrawing Chamber

‘..An other sute of hanginges for the same roome being fowre peeces of Arras of the stone of Abraham, every peece ,twelve foote deep. The pictures of the Queen of Scottes, the same Queene and the King of Scotes with theyr Armes both in one, the King and Quene of Scotes hir father & mother in an other, the Erie of Leycester, Sir William Seynttowe, the prodigail sonne, Marie Countess of Shrouesbury, Sir Charles Cavendishe, Sir Charles his first wyfe, Ulisses and Penelope, a drawing table Carved and guilt standing uppon sea doges inlayde with marble stones and wood, a Carpet for it of nedleworke of the stone of David and Saule.’

Long Gallery

‘In the Gallenie: Thirtene peeces of deep Tapesthe hanginges of the stone of Gedion every peece being nynytene foote deep…’

‘The Pictures of Quene Elizabeth, Edward the second, Edward the third, Rychard the third, Henry the fourth, Henry the fyft, Henry the sixt, Edward the fourth, Richard the third, Henry the seaventh, Henry the Eight, Edward the sixt, Quene Marie, Quene Elizabethes picture in a less table, The King of Fraunce, Henry King of Scottes, James King of Scottes, The picture of Our Ladle the Virgin Marie, Queen Anne, Henry the third King of Fraunce in a little table, The Duke of Bullen, Philip King of Spayne, Twoo twynns, Queene Katherin, the Erie of Southampton, Mathewe, Erie of Lenox, Charles, Erie of Lenox, George, Erie of Shrouesbury, My Ladle, Lord Bacon, The Marquess of Winchester, the Ladle Arabella, Mr Henry Cavendishe, The Lord Straunge, The Lord Cromwell, Mrs Ann Cavendish, The Duke of Sommerset, Sir Thomas Wyet, The storie of Joseph, a looking glass set with mother of peanie and silver, a table of Iverie carved and guilt with little pictures in it of the natyvitie the picture of hell.’