Figurative painting can be considered dishonest as the artist must use techniques to fool the viewer into thinking the two-dimensional pattern represents a three-dimensional object. Figurative painting also suffers from comparison with photography. A camera can apparently capture in an instant what a painting must spend hours or days recreating.

Before considering it as representing something else a sculpture can be analysed as itself. This can also be done with a painting if we get up close and consider the brushwork. A sculpture can also refer to someone or something else.

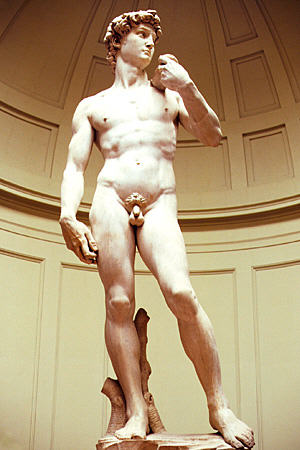

Slide 1: Michelangelo, David. Florence, Accademia

A surprising aspect of Michelangelo’s David is that it is big, much bigger than the young man it represents. We accept this use of scale as one of the uncontroversial rules of sculpture. Sculpture if often placed on a plinth to separate it from the world and the plinth signifies that it is a work of art.

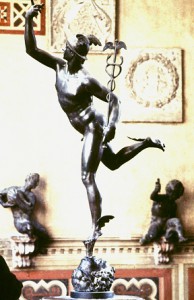

Slide 2: Giambologna, Mercury. Florence, Bargello (search Google for image)

Sculpture can also take the form of carving into a flat surface, called bas-relief.

Slide 3: Nicola Pisano (c.1220/1225–c.1284), Charity. Pisa Baptistery Pulpit

Nicola Pisano is sometimes considered the founder of modern sculpture. He is best known for the Pisa Baptistery Pulpit, the pulpit of Sienna Cathedral and the Great Fountain at Perugia (1277–1278). The pulpit in Sienna and the Great Fountain were completed by his son Giovanni Pisano (c.1250–c.1315).

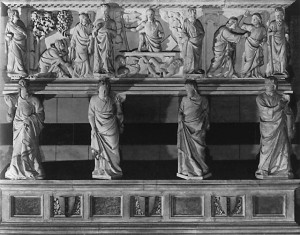

Slide 4: Andrea Pisano, panels from Florence Baptistery south doors

Andrea Pisano, panel from Florence Baptistery south doors

Andrea Pisano (1290-1348) was trained by Giotto di Bondone. Of the three world-famous bronze doors of the Baptistery in Florence, the earliest one on the south side was Pisano’s work; he started it in 1330 and finished in 1336. In 1347 he became Master of the Works at Orvieto Cathedral where he was succeeded by his sons Nino and Tommaso.

Slide 5: Tino di Camaino, Councillor. Pisa, Mus dell’O. (search Google for image)

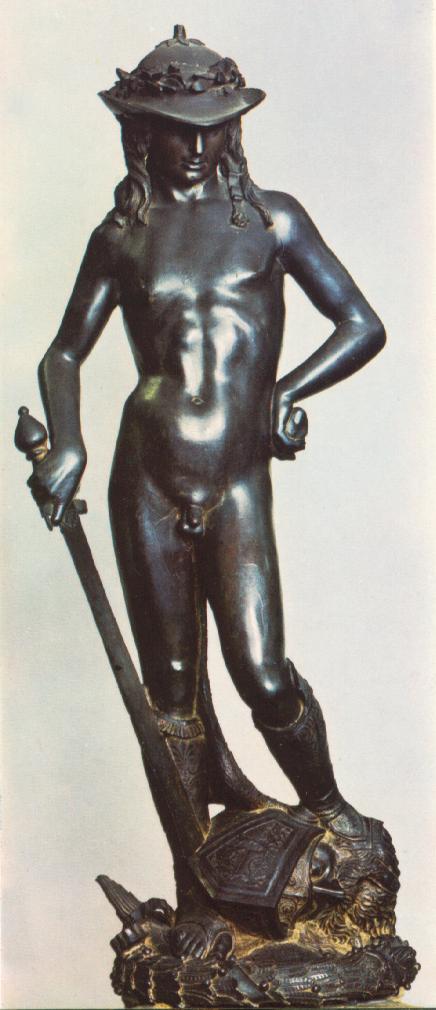

Slide 6: Donatello, David Florence, Bargello

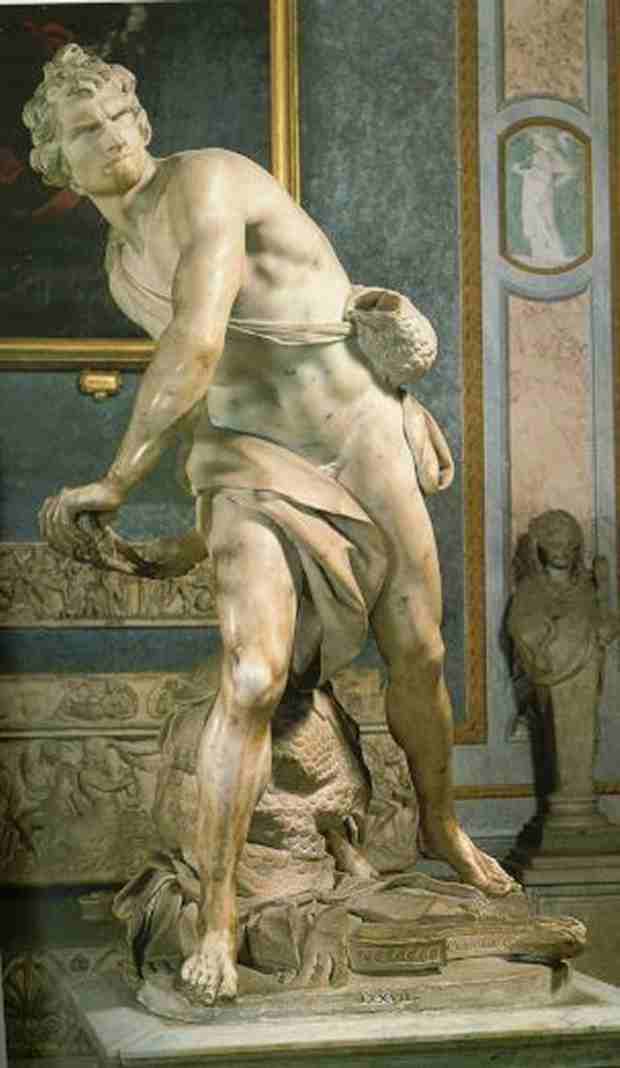

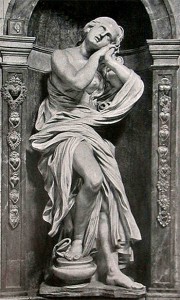

Slide 7: Bernini, David. Rome, Villa Borghese

It was Cardinal Scipione Borghese who commissioned the statue of David, confronting the giant Goliath and armed only with a sling, executed between 1623 and 1624 by twenty-five year old Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The youth’s tense facial expression is modelled on Bernini himself as he struggle with his tools to work the hard marble. The oversize cuirass leant to David by King Saul before the encounter lies on the ground with the harp David will play after his victory, which is decorated with an eagle ‘s head, a symbolic reference to the Borghese family.

The number of points of view the sculptor intended to present to the spectator is still a matter of conjecture. The right side shows David ‘s movements, his stride is almost a leap as he aims his sling; seen from the front the pose is frozen, just one second before the fatal shot, and seen diagonally there is a rhytmic balance between movement and pose.

Slide 8: Michelangelo, David, detail, torso

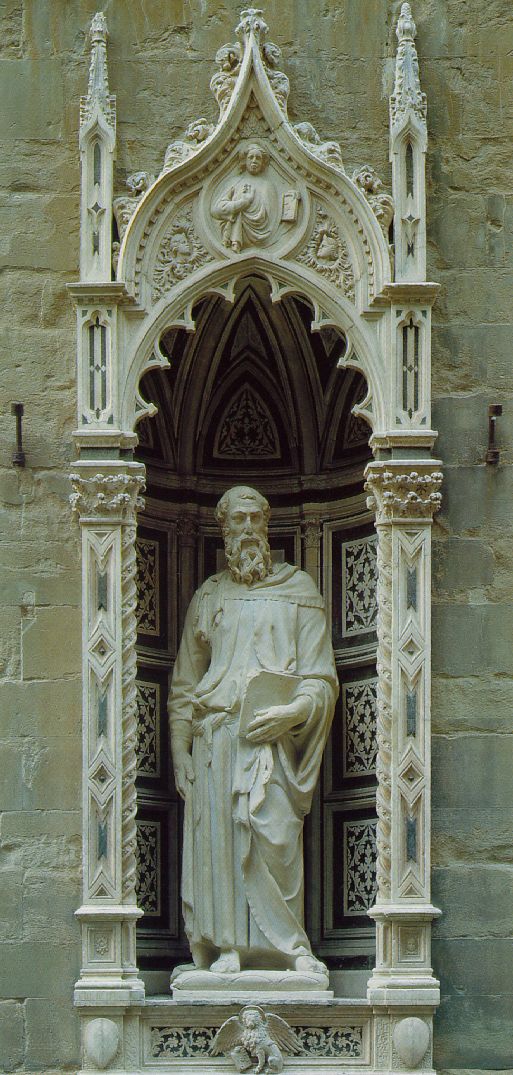

Slide 9: Donatello, St Mark. Florence, Orsanmichele

Donatello, St. Mark, 1411-13, marble, height 236 cm, Orsanmichele, Florence

Slide 10: Matisse, Slave. London, Tate (search Google for image)

Slide 11: Giambologna, Astronomy. Florence, Palazzo Vecchio

The beautiful young woman depicted in this statuette is an allegory of astronomy as can be deduced from her attributes: prisma, armillary sphere, straight edge, ruler, plumb and drawing compass. Because of these attributes the sculpture in old inventories was listed as Venus Urania. It marks the culmination of Giambologna’s efforts to form the perfect nude. The beauty of its spiral composition demands appreciation from an infinite number of viewing positions. The statue was executed in 1573, and it was at about the same time that the artist created his Apollo sculpture for Francesco de Medici’s studiolo. The figure of Astronomy is its compositional counterpart.

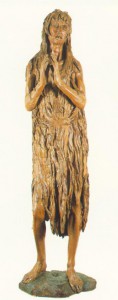

Slide 12: Donatello, Magdalen. Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo (search Google for image)

Slide 13: Bernini, Magdalen. Siena Duomo, Chigi Chapel (search Google for image)

Slide 14: Nicola Pisano, Presentation. Pisa Bapt Pulpit

Slide 15: Donatello, Feast of Herod. Siena Bapt, font

Slide 16: Donatello, Ascension. London, V&A (search Google for image)

Slide 17: Donatello, Deposition. Florence, S. Lorenzo

Slide 18: Nicola Pisano, Adoration, Pisa Bapt Pulpit

Slide 19: Donatello, Miracle of Misers Heart Padua Santo

Slide 20: Desiderio da Settignano, St Jerome. Washington DC

Desiderio da Settignano,Saint Jerome in the Desert, 1461,Florentine, 1428 / 1430 – 1464, marble, 42.7 x 54.8 cm (16 3 / 4 x 21 1/2 in.), Widener Collection

Slide 21: Donatello, Limbo I Resurrection. Florence, S. Lorenzo

DonatelloDonato de’ Bardi detto Donatello,Ressurrezione -(Firenze 1386 – 1466)

“From the wide horizons of his vision in the Padua reliefs, embracing the most vast and complex natural and architectural settings along with the dramatic nucleus of the scene, it now seems that the old sculptor narrows his aim to individual episodes, connecting them, however, within a framework articulated in structure by a scenographic realism of extraordinary objectivity. Christ rises laboriously from the sleep of death, a heart – rending figure who towers over the setting of the sacred scene: a power higher than himself draws him from death into life, amidst the lifeless sleep of the soldiers and the now remote – and I would almost say buried – elegance of the weapons and pagan devices.” (Castelfranco).