(These are notes of a course given at Birkbeck College by Carol Jacobi in 2005/2006)

19thC Orientalism and Photography

Orientalism and Photography slides

Slide 1: Gerome, Dance of the Almah, 1863, oil painting

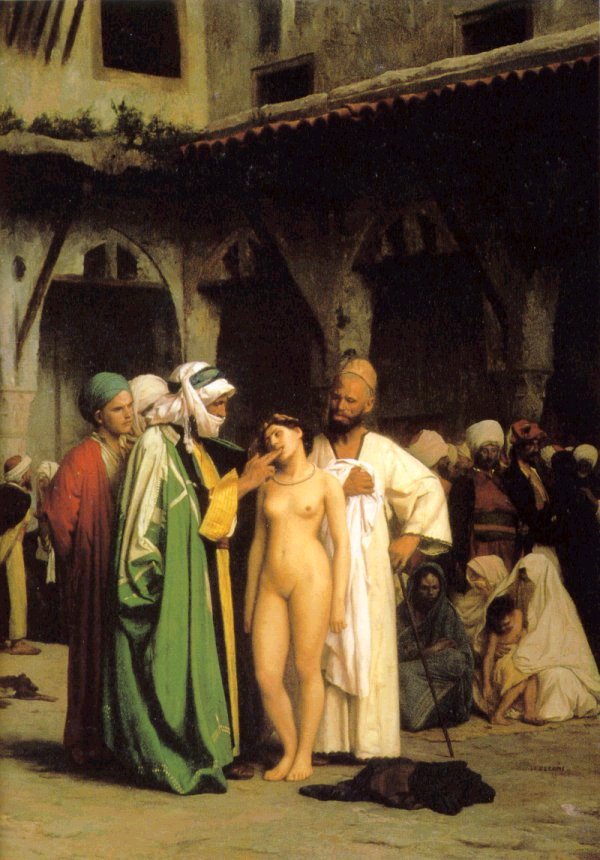

Slide 2: Gerome, The Slave Market, early 1860s, oil painting

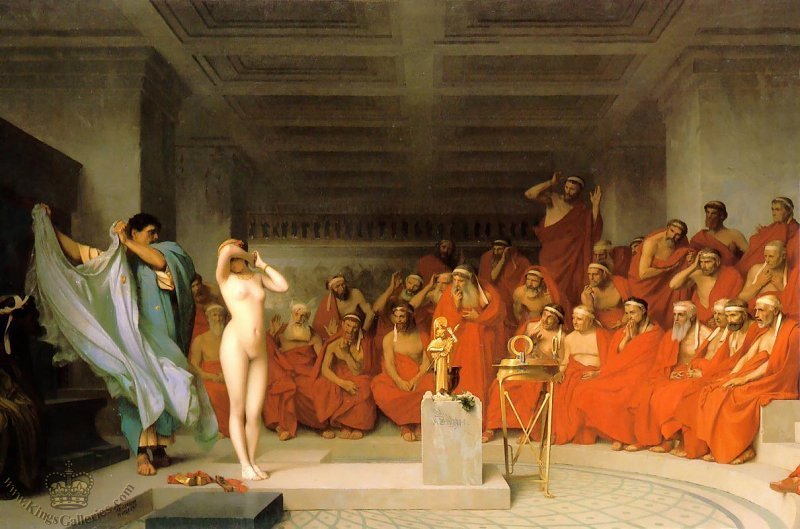

Slide 3: Gerome, Phryne In Front of the Judges, 1861, oil painting

PHRYNE, Greek courtesan, lived in the 4th century n.c. Her eal name was Mnesarete, but owing to her complexion she was called Phryne (toad), a name given to other courtesans. She was born at Thespiae in Boeotia, but seems to have lived at Athens. She acquired so much wealth by her extraordinary beauty that she offered to rebuild the walls of Thebes, which had been destroyed by Alexander the Great (336), Oh condition that the words Destroyed by Alexander, restored by Phryne the courtesan, were inscribed upon them. On the occasion of a festival of Poseidon at Eleusis she laid aside her garments, let down her hair, and stepped into the sea in the sight of the people, thus suggesting to~the painter Apelles his great picture of Aphrodite Anadyomene, for,which Phryne sat as model. She was also (according to some) the model for the statue of the Cnidian Aphrodite by Praxiteles. When accused of profaning the Eleusinian mysteries, she was defended by the orator Hypereides, one of her lovers. When it seemed, as if the verdict would be urifavourable, he rent her robe and displayed her lovely bosom, which,so moved her judges that they acquitted her. According to others, she herself thus displayed her charms. She is said to have made an attempt on the virtue of the philosopher Xenocrates. A statue of Phryne, the work of Praxiteles, was placed in a temple at Thespiae by the side of a statue of Aphrodite by the same artist.

Slide 4: Nadar, study for Gerome, 1860-61, photograph

Slide 5: Delacroix Odalisque, 1857, oil

Slide 6: Durieu, Study of Mile Hamely, photograph from Delacroix’s album of nude studies, c.1854(image not found)

Slide 7: Delacroix, Death of Sardanapalous, 1844 oil

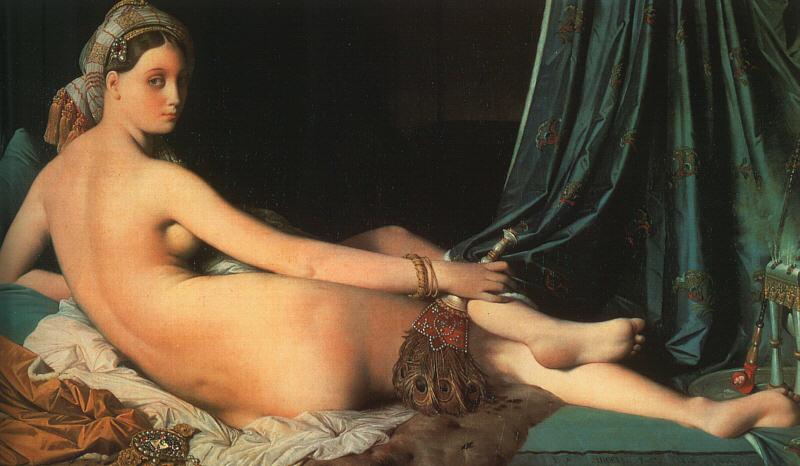

Slide 8: Ingres, La Grande Odalisgue, oil, 1814

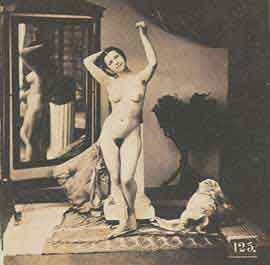

Slide 9: D’Olivier, Nude Studies, photographs, c. 1855

Slide 10: Renoir, Woman of Algiers, 1870, oil

Slide 11: Roger Fenton, Odalisque, photograph, 1856

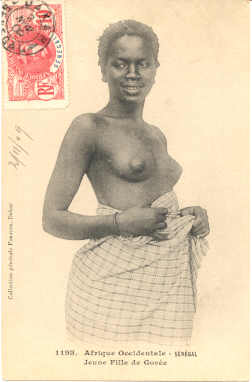

Slide 12: Anon. Postcard photographs of African and Moorish women, late C19

Slide 13: J. F. Lewis, The Hareem, c.1850, watercolour and bodycolour (guache)

Slide 14: Arnoux, The Pacha and His Hareem, Egypt, print from a photograph, 1870-80

ARNOUX, Hippolyte. Un harem en Ciroa. Port Said, ca. 1880, albumen print,, 22,6 x 28,4 cm

Slide 15: J.F. Lewis,An Intercepted Correspondence, Cairo, 1869, oil

Note the correspodence is a bouquet sending the message through the language of flowers

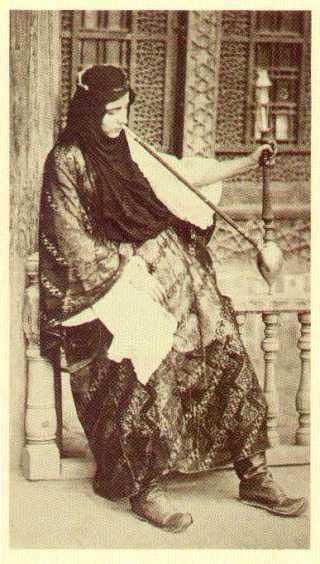

Slide 16: Ali Sami, Portrait photograph of his fianc'e, Istanbul, 1880

Slide 17: Anon, Studio portrait, Istanbul, late c19th

Slide 18: Holman Hunt, The Afterglow in Egypt, 1854-63

Slide 19: Hannauer, A young unmarried woman from Bethlehem, c.1902 (anthropometry)

An image of a woman being studied using anthropometry

Slide 20: Holman Hunt, The Great Pyramid, 1854 (water-colour and body-colour)

Slide 21: Francis Frith, Pyramids from the Southwest, Giza, 1858, (photograph)

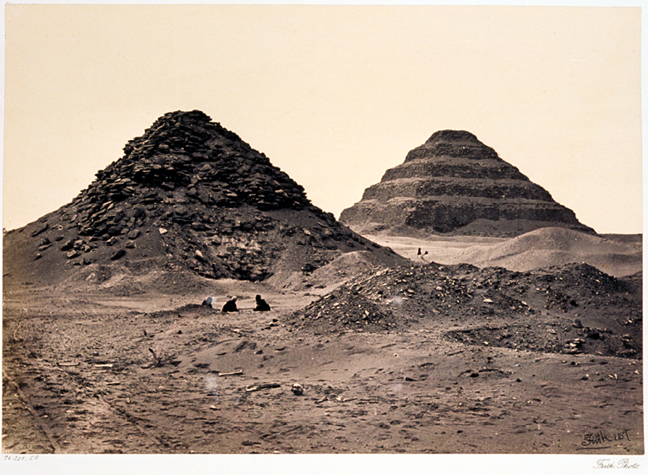

The Pyramids of Sakkarah From the North-East

Sinai, Palestine, The Nile. ca. 1863

ca. 1857 / print ca. 1863

PUBLISHER: Mackenzie, William

albumen print

16.4 x 23.1 cm.

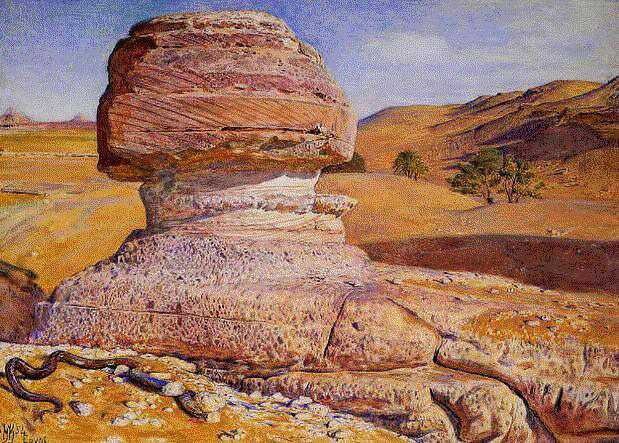

Slide 22: Thomas Seddon, Excavations Around the Sphinx, 1856 (water-colour)

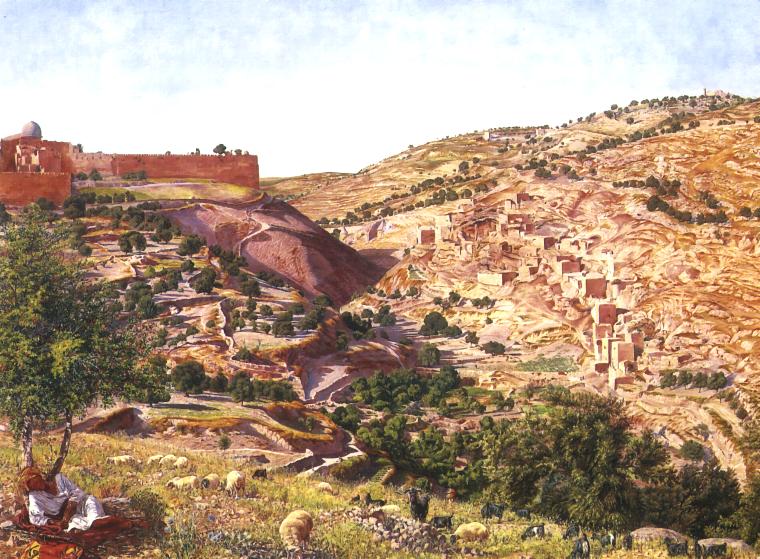

Slide 23: Francis Frith, Pyramids and Sphinx, Egypt, 1856 (photograph)

Francis Frith English, Egypt, 1858 Albumen print Sheet: 15 9/16 x 19 5/16 in.

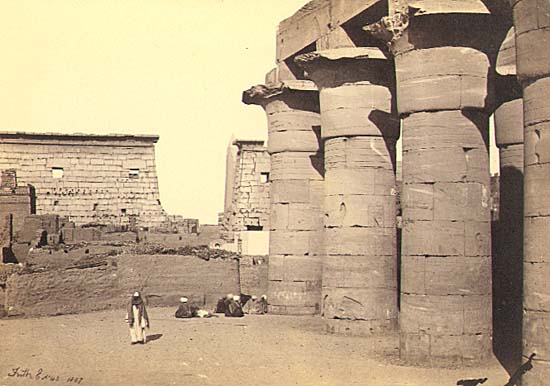

Slide 24: Francis Frith, Luxor, Egypt, 1856 (photograph)

Slide 25: Anon, ‘Scenes from Eastern Life’, Illustrated London News, 1893

Slide 26: Anon, ‘Mussulman Ladies at Home’, The Lady’s Realm, 1898(image not found)

A Brief French History of Postcards

The first officially released postcard was in Austria on October 1, 1869. In France during the war of 1870, the “Company of Help” (future Red Cross) were allowed to circulate postcards without stamps to the wounded. At the same time, the government was trying to reduce the transport of mail by balloons. They authorized the use of a “Chart-Station” in the format of 7 X 11 cm, referring to the postcard. Officially on December 20, 1872, the French National Assembly voted a finance law which mentioned for the first time the concept of “postcard”. The law was enacted January 15, 1873.

First French Postal Card 1873

In 1878, the standardization between the European states changed the dimensions of the postcard to the traditional format 3'” x 5'”. This was referred to the “Sage Type” postcard. A tariff was imposed and marked on the postcard. The stamp (or tariff) for the “Sage Type” postcard is now directly printed on the front of the card. leaving the back without illustration, reserved for correspondence.

There were very few illustrated or photographic postcards before 1897. These rules applied to both illustrated and photographic images on postcards from Europe. In 1900, the image is allowed to occupy only one negligible part on the front of the card.

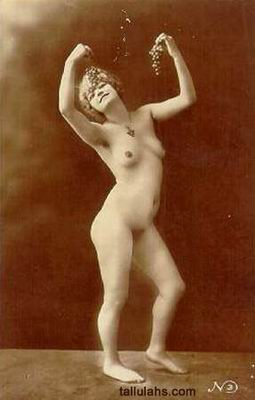

Early French Risque Postcard

In 1903-1904, the image can now fill the entire front but must have a very small margin of white bordering the image. By 1905, the image now covers the entire front and does not change for 20 years. During mid to late 1920’s, postcards were allowed to have a serated edge, though it was not mandatory.

Why Nudes Have a Plain Back

A majority of nude postcards were called postcards because of the size. They were never meant to be postally sent. It was illegal. The heads of the different countries producing these postcards had regular meetings to determine what was legal in their country and what was not.

The nudes were marketed in a monthly magazine called the “La Beaute”. They targeted artists looking for poses. Each issue contained 75 nude images which could be ordered by mail, in the form of postcards, hand-tinted or sepia toned. Whilst the photo reproduced in the magazine was lightly retouched, the postcards sent to the home address were complete. Of course, not only artists took advantage of this means of obtaining nude images. There were street dealers, tobacco shops, and a variety of other means of marketing to American tourists.

“La Beaute” Magazine Ad for Nudes, 1923

Dating Your Postcards

It is easy to date a postcard which travelled by the date of the postal seal or the handwritten indication of its correspondent. It is more difficult to know the date of the photographic postcard, especially if it does not present a precise event and is in the largest majority of French postcards.

In spite of these facts, we have several means to date these cards:

The Back of the Postcard:

On November 18, 1903, the postal service authorized the address on the right part and the correspondence on the left. Thus, if the back of the card is NOT divided it was published before December 1903. If the back IS divided into two parts, the card was produced after December 1903.

The Stamp:

The stamp gives very little indication of the date because the value rate for stamps did not change until 1917. Many of the tariff stamps are under the postal stamp, making it more difficult to date the card. If you identify the tariff stamp on the card, note the lower the tariff, the older the card. A tariff of 1 centime dates 1900. A tariff of 5 centimes dates 1905. Stampings with 5 centimes were used only for nonpersonal correspondence and the mention of the word “Postcard” was often replaced by “Printed Paper Form”.