(These are notes of a course given at Birkbeck College by Carol Jacobi in 2005/2006)

19thC Art and Mechanical Reproduction

This class will concentrate on nineteenth-century innovations in reproducing images, culminating in the 1880s with the application of photography to painting and the development of photomechanical reproduction. Consideration will be given to how these innovations helped to define the role of the artist and some examples of artists’ printmaking in the second half of the nineteenth century will be examined.

Art and Mechanical Reproduction – Slide List — 16/11/04

Slide 1: Octave Tassaert, The Piano, c. 1830

I could not find The Piano so found another Tassaert print

Slide 2: Mary Ann Hobart scrapbook album, 1837 – 73. Early page with lithographs(image not found)

Slide 3: As above, later page with wood engravings(image not found)

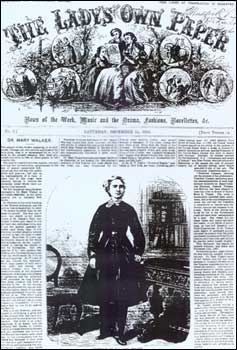

Slide 4: The Lady’s Own Paper, ‘Mrs Jameson’, 1867

Cover of The Lady’s Own Paper showing Dr Mary Walker wearing bloomers. The paper reported that Dr Walker felt it was not safe or hygienic to practice medicine in long dresses and that she believes ‘that long dresses are killing women; and she attributes the failure of the Bloomer movement, some years ago, to the circumstance that the ladies who favoured it then were for the most part incapable of appreciating and explaining the physiological, hygienic, and moral bearings of the question’.

Slide 5: The Lady’s Own Paper. ‘Elizabeth Barrett Browning’, 1868

This is the image of Elizabeth Barrett Browning which was on the front of the ‘lady’s own paper’.

Mrs Jameson from Lady’s Own Paper

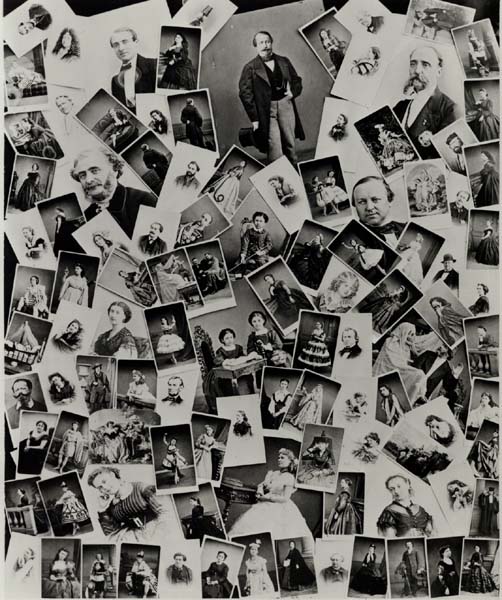

Slide 6: French album, portraits of artists, 1850-1 860.

Slide 7: Prince Albert’s album of photographic reproductions of Raphael’s drawings for Agony in the Garden, photos by Caldesi, published by Colnaghi & Agnew(image not found)

Slide 8: Photographic album with printed floral decoration, c. 1870

Slide 8 (art & mech reproduction) An example of a photographic album with printed floral decoration.

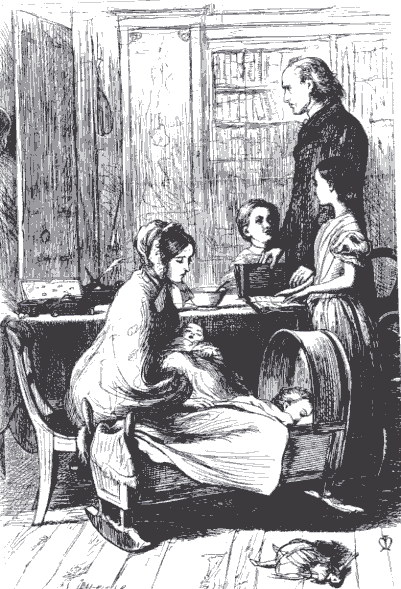

Slide 9: Millais, ‘Grandmother’s Apology’, 1859. Illustration for Once a Week

Alfred Tennyson

“The Grandmother’s Apology”

from Once A Week 1.3 (16 July 1859): 41-43. Throughout his later career, Tennyson’s poems often appeared first in periodical form, as here, with an illustration by the Pre-Raphaelite artist John Everett Millais. As with many of Tennyson’s works, “The Grandmother’s Apology” was quickly reprinted in an American periodical — in this case, Harper’s Weekly.

Slide 10: Millais, Illustrations for Trollope’s Novels, see handout.

John Everett Millais, “The Crawley Family”

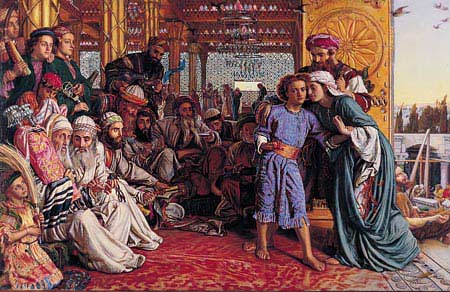

Slide 11: Holman Hunt, The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, 1867, see hand out

Slide 12: Thompson (Lady Butler), ‘The Roll Call, 1874 (see handout)

Thompson (Lady Butler) ‘The Roll Call’ 1874

Slide 13: Millais, ‘Bubbles’, see handout.

1886 Used for poster for Pear’s soap

Slide 14: Vallou de Villenueve, ‘Nude Study’ for Courbet Les Baigneuses, 1853

Julien Vallou de Villeneuve

French, 1795-1866 A painter who exhibited at the Paris Salons from 1814-40, Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (born in Boissy-Saint-L'ger) was later known as a lithographer. He became interested in photography in 1842, shortly after the new medium’s invention, as an aid to his graphic work. His subjects included fashion, costume, and daily life, as well as light erotica, sometimes published in conjunction with other artists. By 1850 Vallou de Villeneuve had begun to practice photography in his studio, primarily female nudes and portraits of actors. In 1853-54 he published a series of nude studies, 'tudes d’apr's nature, which were sold as artists models and to the general public. Several were used for well-known works by Gustave Courbet. Vallou de Villeneuve’s works are admired for their emotional restraint, as well as for their masterful orchestration of form. A member of the Soci't' h'liographique in 1851, he helped found the Soci't' française de photographie in 1854. T.W.F.

Slide 15: Courbet Les Baigneuses, 1853

Slide 16: Aubrey Beardsley, illustration for the Yellow Book, 1890.

Aubrey Beardsley, cover design for The Yellow Book, Vol 1, April 1894

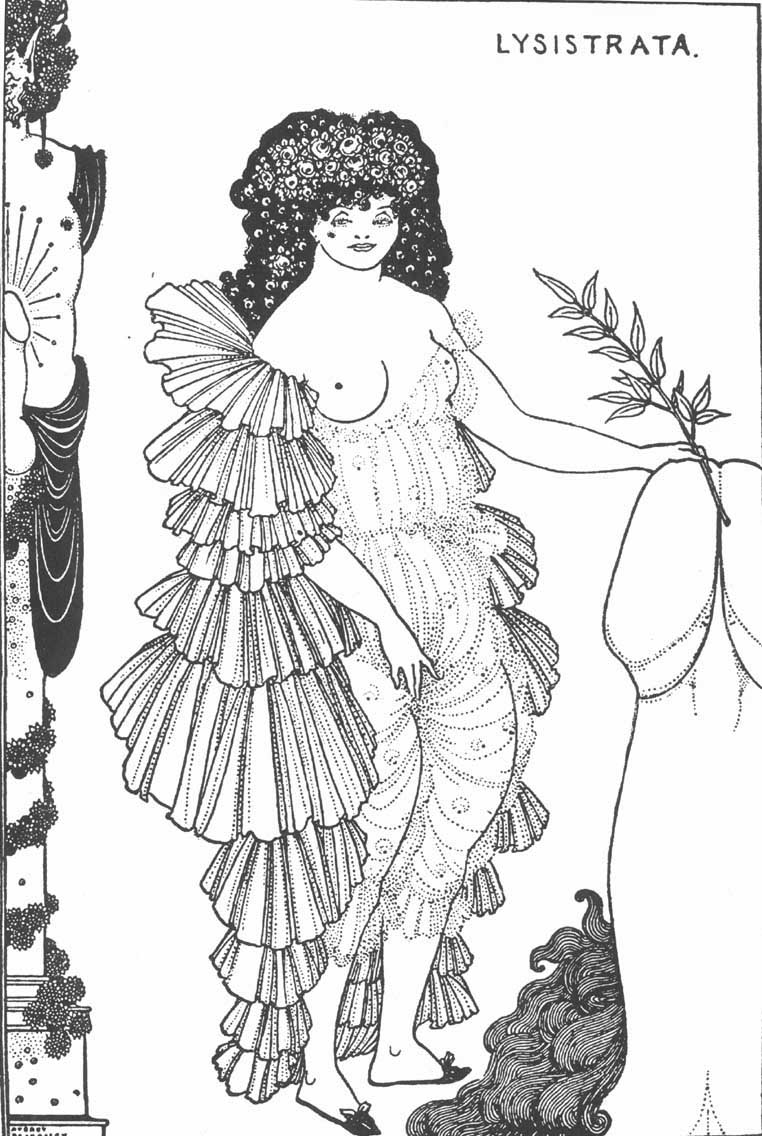

Slide 17: Beardsley, Lysistrata, 1896.

LYSISTRATA, the third and concluding play of Aristophanes’ War and Peace series, was not produced till ten years later than its predecessor, the Peace, viz. in 411 B.C. It is now the twenty-first year of the War and there seems as little prospect of peace as ever. A desperate state of things demands a desperate remedy, and the Poet proceeds to suggest a burlesque solution of the difficulty. The women of Athens, led by Lysistrata and supported by female delegates from the other states of Hellas, determine to take matters into their own hands and force the men to stop the War. They meet in solemn conclave, and Lysistrata expounds her scheme, the rigorous application to husbands and lovers of a self-denying ordinance–“we must refrain from the male altogether.” Every wife and mistress is to refuse all sexual favours whatsoever, till the men have come to terms of peace. In cases where the women must yield ‘par force majeure,’ then it is to be with an ill grace and in such a way as to afford the minimum of gratification to their partner; they are to be passive and take no more part in the amorous game than they are absolutely obliged to. By these means Lysistrata assures them they will very soon gain their end. “If we sit indoors prettily dressed out in our best transparent silks and prettiest gewgaws, and all nicely depilated, they will be able to deny us nothing.” Such is the burden of her advice. After no little demure, this plan of campaign is adopted, and the assembled women take a solemn oath to observe the compact faithfully. Meantime as a precautionary measure they seize the Acropolis, where the State treasure is kept; the old men of the city assault the doors, but are repulsed by “the terrible regiment” of women. Before long the device of the bold Lysistrata proves entirely effective, Peace is concluded, and the play ends with the hilarious festivities of the Athenian and Spartan plenipotentiaries in celebration of the event. The drama has a double Chorus–of women and of old men, and much excellent fooling is got out of the fight for possession of the citadel between the two hostile bands; while the broad jokes and decidedly suggestive situations arising out of the general idea of the plot outlined above may be “better imagined than described.”

http://www.theatredatabase.com/ancient/aristophanes_005.html