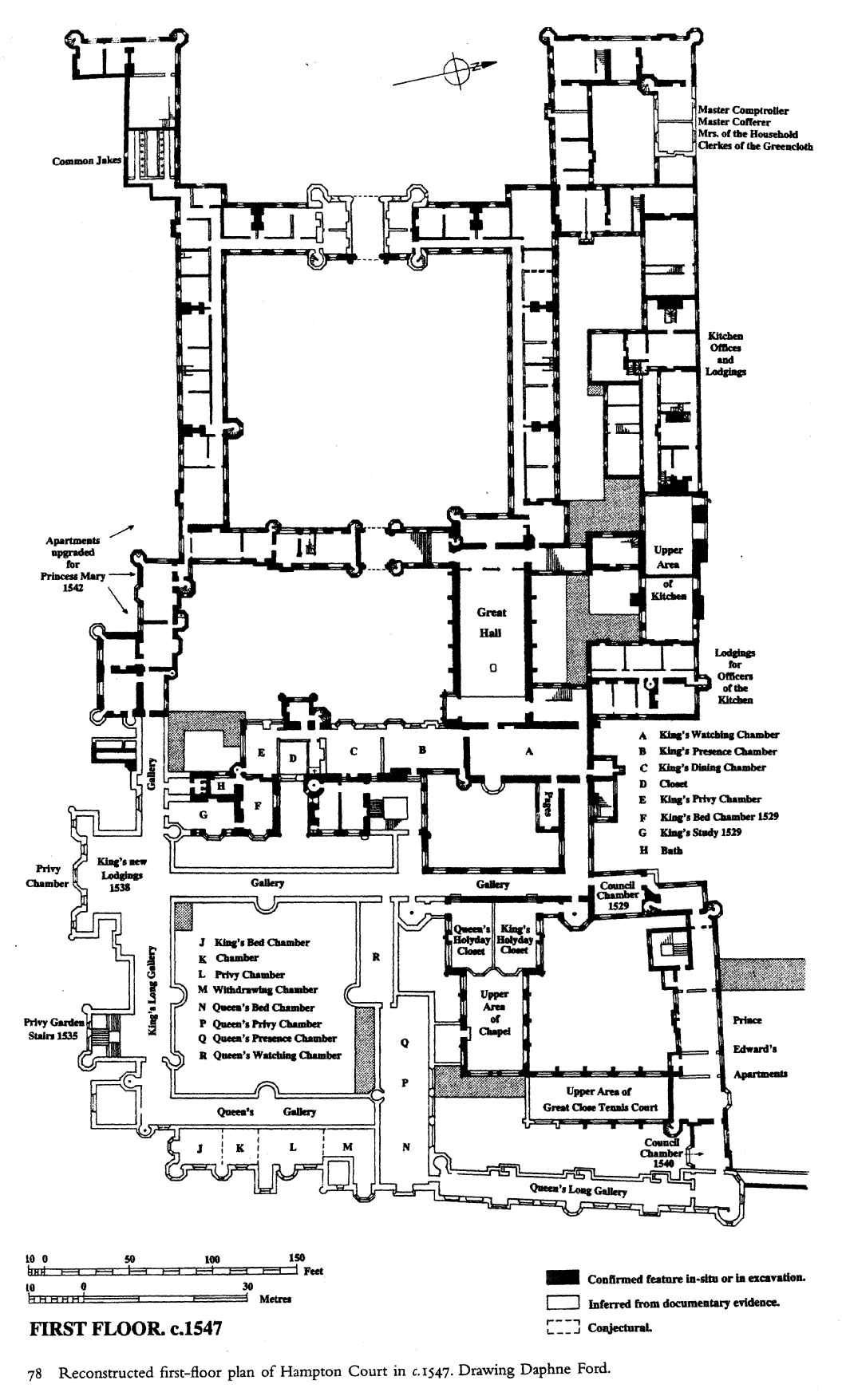

Hampton Court is the only surviving Tudor Royal Palace and so it is an extremely important building. If possible, you should take the opportunity to visit Hampton Court using the following map which shows the existing Tudor walls in black and the original Tudor walls in white. The Palace is entered in the middle at the top (West) of the map. Note that the walls in white were replaced by the Christopher Wren building to the East (bottom of the map).

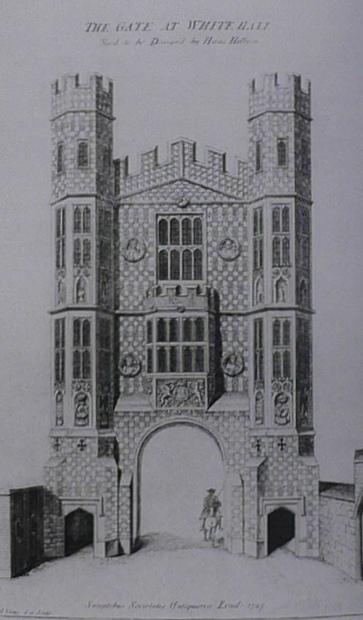

Starting at the front gatehouse it is interesting to point out that this was not the main entrance for Henry VIII and foreign dignitaries who arrived by barge from London. The two roundels are from the ‘Holbein Gate’ on which we know there were four roundels. When it was demolished in the 18th century two were later thought to belong to Hampton Court and so were fixed to the gatehouse.

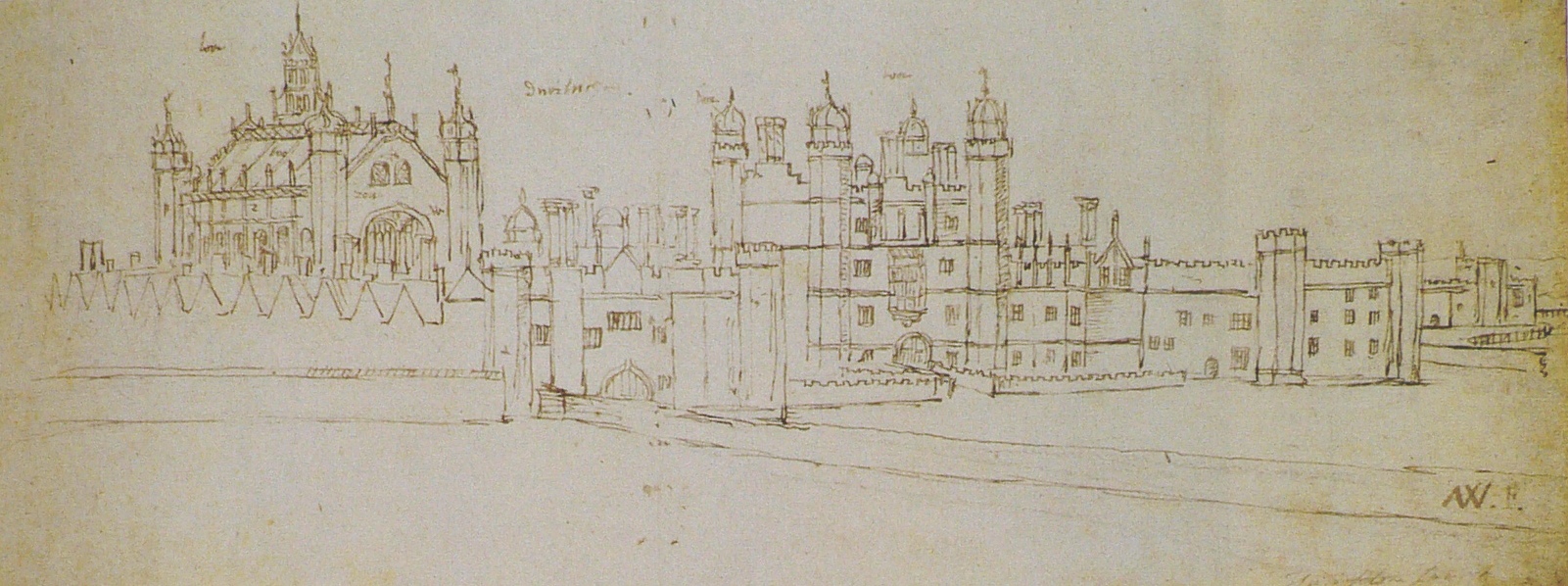

There are no roundels on the gatehouse on the Wyngaerde’s engraving of 1558.

The terracotta roundels in the Inner Court are 1521 and they are all of Roman emperors.

The moat was excavated in the nineteenth century at a cost of several million pounds and it is not designed for water to be added. The sculptures of medieval symbols on the bridge over the ‘moat’ are not original. Note that the gatehouse was originally five stories and the towers were surmounted by golden domes.

Henry VIII took over the palace in 1529 and made it a Royal Palace which then needed to serve 2,000 people when he was present. He therefore extended Wolsey’s palace by adding the wings either side of the gatehouse. The one to the north was for receiving goods from suppliers for the kitchens behind and the one to the south was the “Great House of Easement” and it housed 14 lavatories in two rows of seven on two floors. They dropped into a waste pit that was cleaned out annually into the river by someone who was partly paid in rum (for obvious reasons).

Henry VIII arrived by barge and entered by the gatehouse on the river and reached the house by covered walkways. Today’s main entrance was therefore a back entrance and the goods arrived through the wing to the north.

Base Court or ‘Basse Court’ (lower court)

In many houses the outer courtyard was made of canvas and timber and so they have all disappeared. To the south (the right on entering) is the oldest brickwork. A great deal of brickwork was replaced in the 19th century and all the stonework as it is soft Reigate stone. We can still see the diaper work made of blackened bricks (‘burn the headers’ by placing the ends of the brick in the furnace after they have been fired to blacken them). The stone was whitewashed and the brick painted in red ochre so the orange bricks stood out against the black diaper work. Unfortunately, the chimneys are all Victorian and from Wyngaerde’s drawing it looks as if they were originally much plainer. The current design is more Elizabethan (and Elizabeth did not work on Hampton Court). The original courtyard was cobbled.

Normally outer courts were occupied by servants but at Hampton Court they are substantial rooms and pairs of rooms for courtiers. Every room has a fireplace, much needed as it tended to be colder inside than out. An enclosed passage way runs round the courtyard so you can go from room to room without going outside. The chimney stacks are build into the walls and so the outer walls are flat. It was very innovative in 1515-22. The rooms are ‘single pile’, i.e. one room deep.

The outer gatehouse is quite squat like Lambeth Palace compared to the inner (east) gatehouse which is thinner and taller, like that at Cardinal College (now Christ Church). They are made to look medieval with false arrow slits to give Wolsey a (false) heritage. The roundels were by Giovanni Maiano and were painted and gilded.

Thomas Wolsey was made Archbishop of York in 1514 and inherited two small lodgings in Battersea and what is now Whitehall. They had no gust accommodation and so he build Hampton Court to entertain the king and foreign ambassadors, in fact in 1522 he entertained the most powerful man in Europe, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Inner Court

Wolsey took on a 99 year lease (he was not allowed to buy the freehold) and he built over an earlier building built by Daubigny. The walls of the earlier building are marked in red brick on the ground in the inner court.

Henry VIII was continually rebuilding for 10-15 years although a lot of the inner courtyard buildings are 18th century by Wren (note the date 1732). Henry built ‘stacked lodgings’ and a sequence of increasingly private rooms including a ‘Bayne Tower’ (bath tower with Italian tiles, hot and cold running water and even a sauna).

To the north (left on entering) is the Great Hall with its oriel window on the right. It is now believed the hall and oriel window were by Wolsey but that the Hall was rebuilt by Henry as the string course is not at the same level on the hall wall and the oriel window.

The clock is by Nicholas Kratzer (whose portrait was painted by Holbein) but it has been heavily restored over the years. Kratzer was the person who wrote the names on the Holbein portrait of the Moore family. The clock even tells the times of high and low tide, very important if travelling to London to catch a ship. The roundels were originally all concentrated in this inner courtyard and it is difficult to know how much they have been restored over the years.

The coat of arms over the western gatehouse entrance may be by Maiano and it has Corinthian columns and cherubs as well as Wolsey’s coat of arms and even his cardinal’s hat (which was replaced in the 19th century. It survived because Henry’s coat of arms covered it until the 19th century.

We have complete accounts so we know the workmen and we know they also worked on the Henry VII Chapel and King’s College Chapel, Cambridge.

Henry was using 70-80 bricklayers at a time and he continually interfered with the work. He ordered the workmen work 24 hours a day and they worked in shifts by candlelight at night and under canvas when it rained.

Hall

The hammer beam roof is spectacular and original and could have been brightly painted. It looks like and involves some of the design aspects of a ship’s hull. The hammer is the horizontal beam coming out of the wall with a small portrait in themiddle. The spandrel below contains the royal coat of arms. When the roof was restored a small badge of Anne Boleyn (queen 1533-6 following Catherine of Aragon queen for 24 years, 1509-1533) was discovered which was unusual as when Henry’s wife changed all the signs and symbols of the old queen were removed. Anne’s symbol was a leopard and this was changed to a panther, Jane’s symbol (queen 1536-7, followed by Anne of Cleves, 1540, whose marriage was annulled, then Catherine Howard 1540-1 who was executed and finally Catherine Parr 1543-47). The badge is an ‘H’ intertwined with an ‘A’ in a lover’s knot.

The hall is on the first floor (as was Wolsey’s). Ambassadors would have arrived by barge, walked into the river gatehouse and then through covered walks to the inner courtyard and then up the stairs into the Great Hall.

The fan vaulting in the oriel window looks like that in the window at Cardinal College (Christ Church) and the same craftsmen could have constructed it giving further evidence that Henry re-used it. Wolsey’s hall was slightly smaller although the differences are debatable.

At this time hammer beam roofs were old-fashioned and were from the 14th century so it would not have been used by Henry VIII for dining. There was no fireplace as a Tudor hall would normally have but a square stone block in the centre and formally a exit for smoke in the roof although recent analysis has found no soot so it is likely that it was never used. It is therefore unclear how the hall was heated, perhaps there was thought to be no need to heat a servant’s eating hall. There were so many servants they had to be fed in two sittings.

In 1537 Edward VI was born at Hampton Court and the proud father paraded his son holding him above his head and walking up and down in front of the courtiers (arranged carefully by rank) in the Great Hall. He would have entered to blasts of trumpets and the original floor was tiled so it would have been very noisy.

The stained glass is all Victorian but is similar in style. The stag’s heads are wooden and were put up by James I. The walls would have been completely covered in tapestries bent around corners and chopped to fit around doors. Spaces would have been filled with banners.

The tapestries are the Story of Abraham and were made in Brussels in 1541-2. There were 10 expensively made in silk, gold and silver (accounting for their dull grey tone as silver tarnishes). They were known across the courts of Europe they were so expensive and there were two other versions, one still in Spain, although incomplete. The hall has six and three seem to fit exactly down each side suggesting they were made for the hall. They were rolled up and travelled with Henry when he moved between Palaces. Henry VIII also had the Acts of the Apostles, tapestries based on the Raphael cartoons (now in the V&A with copies at Hampton Court). Charles II used the Abraham tapestries at his coronation so they were still prestigious over a hundred years later. Of the other four tapestries, two are on display at Hampton Court and two are in storage.

Great Watching Chamber

The king’s guard numbering between 70 and 200 (depending on the level of emergency) would have lived and slept in this room and used the garderobe (toilet) to the north. Ambassadors would have changed in what is now called the Page’s Chamber to the east. They would have then entered the Presence Chamber through the door to the south (now bricked up). Past this room was the Privy Chamber. They are leather mache roundels on the ceiling and the battens are wood. This was a standard type of roof.

Through the door on the right is the Page’s Chamber, a good reconstruction of a Tudor room.

In the corridor is a portrait of Edward VI by the workshop of William Scrots, a Netherlandish painter who replaced Holbein as the court painter. The full length pose in front of a classical column and curtains was a typical mid-16th century European court painting. Edward was king in 1547 and was a very eligible bachelor in Europe.

There are three major paintings in the ‘Haunted Gallery’ (note that they might have moved into the picture gallery, please ask the staff):

- The Embarkation of Henry VIII from Dover

We do not know the painter of this view of Henry VIII embarking for France and it is dated about 1540. There is a country house that has similar scenes of the adventures and victories of Henry.

- The Family of Henry VIII

Showing Henry with Edward to his right and Jane Seymour, his mother, to Henry’s left. Also in line to the throne were Mary to Henry’s right and Elizabeth to his left. It is recorded as at Whitehall at the end of the 16th century. We don’t know the painter and it is dated 1545 based mostly on the probable age of Edward. Edward looks very ill with bags under his eyes. Note the wall is carved and gilded and the floor is plaster painted to look like marble. We see views of the Privy Gardens at Whitehall that were built at this time. Will Summer, Henry’s fool, is shown on the right.

The painting is divided into three like an altarpiece, a triptych. Did this mean it had religious associations and is it going to far to ask if Henry and his son would be equated with Christ and the Virgin Mary with saints either side? The princesses are wearing French hoods that became unacceptable when Anne (who dressed in the latest French fashions) was executed. Jane has a different style. Clothes are good for dating but be careful as some older sitters wore old-fashioned clothes.

- Field of the Cloth of Gold

Unusually we see Wolsey to the right of Henry even though this was painted in c. 1545, 20 years after the event when Wolsey was out of favour. It is the only early 16th century image of Wolsey and agrees with the late 16th century images of Wolsey that were probably based on contemporary pictures of him that no longer survive. Note the Renaissance features of the palace combined with the medieval arrow slits and crenelations.

The head of Henry VIII has been cut out and sewn back again. One suggestion for this is that when James I was trying to make peace with Spain in the early 17th century his civil servants remembered the painting at the last minute as he was walking sown the corridor with the Spanish ambassador. Spain still hated Henry as he had shamed them across Europe when he divorced Catherine of Aragon so the civil servants cut of his head and later sewed it back again. We do know this happened from written records but we do not know for sure which painting was referred to.

The dragon at the top left probably refers to a giant firework which was going to be the climax of the celebration before someone set it off accidentally.

We see Henry and François fighting at the top of the picture and a jousting yard at the top right. On the right is a gigantic oven needed to feed the thousands of people and in front of the palace is a fountain that spouted wine until the drunken fighting caused it to be stopped. Wolsey organised the whole event and Henry and François each paid their own way. So that neither king would be disadvantaged the landscape was levelled so when they walked towards each other they would be at the same level. The town on the left is Guisne (pronounced ‘Guys-ner’) and Calais is above it in the distance.

It went off well thanks to Wolsey who was well known across Europe for his banquets. At one banquet he had a nine foot jelly.

Off the ‘Haunted Gallery’ are two Holy Day Closets for the king and queen to worship. Henry used to work in his Closet every day with the window down to the Chapel open so he could hear the service as he worked at his writing desk in front of his fire. He went downstairs to the Chapel once a year at the Feast of Epiphany wearing his crown to associate himself with the three kings of the biblical story. The processional routes went from the King’s private rooms through the Great Watching Chamber and down the ‘Haunted Gallery’ then downstairs to the Chapel.

Outside the Chapel are four cupids ‘bad enough to be English’. They look like some English craftsman trying to copy an Italian cupid. They were moved from elsewhere in the place and would have been brightly painted and gilded. The crowns are heavily restored.

Note the bare brickwork of the corridor, it would have been whitewashed and bright and modern looking.

An early curator spent her lifetime studying al the bricks of the Palace to date each wall but the bricklayers used to reuse bricks from earlier periods so much of her life’s work is wasted.

The Chapel was remodelled by Christopher Wren so is not relevant to Tudor studies but the ceiling is the original hammer-beam roof. It was made in Sonning, Berkshire and moved to Hampton Court by river where it was assembled on site and painted blue and gold. It has Renaissance elements, such as cherubs with medieval elements (such as the hammer-beam). It is possible it was commissioned by Wolsey and taken over by Henry.