William Scrots (?), Princess Elizabeth (Royal Collection), c. 1546/7

A US psychologist writing in The Times claimed she saw evidence in her look that Elizabeth had been sexually abused by Henry as a child. Such speculation can form no part of a proper art historical analysis.

We do see what looks like an elegant, demure, intelligent young woman who we know was trained in many languages and could play the virginals. We also see a resemblance to the pose in Holbein’s Christina of Denmark.

The large book on the stand is probably the Bible and the fact that it has no text on the page (we know from microscopic analysis that it has not worn off) was simply a convention of the time rather than a political statement about the Bible. When Elizabeth came to power she kissed the English translation of the Bible when she entered London.

She is probably holding a prayer book and this suggests to the viewer at the time that she was a good Christian who did not waste her time on idle matters. Of course, at this time there was no thought that Elizabeth would ever become queen as she was third in line after Edward and Mary. She was simply marriage fodder to form some useful political alliance with another country in Europe. The prayer book shows she was a safe bet as a wife and would cause no trouble.

The prayer book may be attached to the belt round her waist, known as a girdle book, to show that it was always with her to be read at any spare moment. This was a common convention all over Europe. Note that it has a bookmark in it and she even has a finger marking a page showing it is a well read book that she has been interrupted reading for the painting to be done.

When she becomes queen the demand for her portrait becomes enormous from all over Europe, as it was for any new monarch.

Anon, Elizabeth I (NPG), c. 1560-65

This portrait and others like it date from the early part of her reign and shown the uniquely English flat, unmodelled face. Roy Strong explains this as due to the lack of painting talent in England and it is true that letters were written complaining of the poor painting skills used to produce Elizabeth’s portraits, for example, from Catherine d’Medici “I must declare she did not have good painters”. Compare this with the earlier Antonio Mor:

Antonio Mor, Mary Tudor (Prado), 1554

But was it the result of poor painters or was it a style that was adopted for specific reasons. We do not know but for example, Elizabeth’s portrait is more hieratic, that is, highly restrained and formal, it distances the viewer from Elizabeth. She is not shown as a crude lifelike image to be ogled but as a timeless, icon of a queen. We do not know to what extent Elizabeth herself had any control of these images. They may have been produced by artists who had never seen her. We must also remember that painters in London were members of the Painters and Stainers Guild and would have also painted inn signs, furniture and banners. In other words they were not artists as we understood the term and as it was understood in Italy at the time, they were craftsmen producing images.

Anon, Phoenix Portrait, c. 1570s

There were also awful, poor quality pictures of Elizabeth circulating and in France there were also scurrilous portraits, for example, one showing her riding her potential bridegroom and exposing her backside.

We know that when someone at a European court complained about Elizabeth’s portrait the Earl of Sussex said “I answered at the first that the portrait bore no resemblance to your Majesty.”

Draft proclamation written by Sir William Cecil in 1563 (Note that there is no evidence that the proclamation was ever put into practice) in which forbids the queen s subjects:

from painting, graving, printing or making of any portrait of her Majesty, until some special persone that shall be by hir allowed … shall have first finished a portraiture therof, after which finished, hir Majesty will be content that all other payntors, or gravors … shall and may at ther plesures follow the sayd patron or first portraictur.

Note that a proclamation or Royal Proclamation is a way for the monarch to pass a law without the agreement of Parliament. The range of issues allowed was limited, for example, the monarch could not pass laws to raise taxes.

This excerpt also tells us that portraits were copied a lot in different media and that no approval system existed. It is possible it was drafted because of scurrilous images but we known such references were worded differently and the word ‘offence’ would not have been strong enough.

We also know that in 1573 the Painters and Stainers Guild petitioned for a restraint on the uncontrolled production of Elizabeth’s images although nothing was done about this either.

Finally, in 1596 George Gower was instructed to search out portraits that could cause offence and destroy them. But by 1596 Elizabeth and her courtiers were very sensitive about depictions that showed her age as they raised questions about the succession.

The Phoenix and Pelican portraits are sometimes attributed to Nicholas Hilliard but we don’t know who painted them. Note the extraordinary detail in the dress and we know from detailed inventories of Elizabeth’s clothes that she wore such dresses. There are no other portraits like the Pelican and Phoenix portraits so they could have been painted by a foreign artist in the flat English style in an attempt to find a ‘special painter’ as mentioned in the 1563 draft proclamation. Her dress can be dated to the 1570s which is how we know the date. Of course, Elizabeth may never have seen these portraits.

Zuccaro, Elizabeth I (BM), 1575

Zuccaro was a famous Italian artist who must have received Papal dispensation to come to Protestant England in 1575 (the Popes always hoped Elizabeth would return to the ‘True Faith’). She has the pose of Christina of Denmark and we know that Zuccaro was taken by Holbein when he saw his work in England.

Although it is difficult to interpret symbols and it depends on the context it is possible that in this picture the dog represents fidelity, the ermine next to the dog purity, the column constancy and the snake climbing up the column prudence. Note that columns in pairs represent the columns of Hercules, a symbol adopted by Emperor Charles V.

There is evidence that the Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester was instrumental in bringing Zuccaro to England and we believe he had a similar painting done. It may have been going to far to have the two painted as pendants although Elizabeth is facing in the correct direction for a husband/wife pendant pair. Dudley had contacts all over Italy, including Venice and Florence and he also tried to bring over other artists.

Anon, Darnley Portrait, (NPG), c. 1575

This portrait could also be by Zuccaro as it is the right time. It follows the pose of Isabella of Portugal by Titian.

Titian, Empress Isabella of Portugal (Prado), c. 1548

Elizabeth was also represented in other media, coins, medallions and the Great Seal. For example, a medallion produced after Elizabeth’s recovered from smallpox in the British Museum, 1562. The medallion shows a hand coming from the clouds being bitten by a snake that is rising from a fire. This may allude to St. Paul being bitten by a poisonous snake and surviving through the assistance of God. It is inscribed “si Deus nobiscum, quis contra nos” (If God is with us, who shall be against us).

Whitney, A Choice of Emblems, 1580, si Deus nodiscum, quis contra nos?

His servauntes GOD preserves, thoughe they in danger fall:

Even as from vipers deadlie bite, he kept th’Appostle Paule.

See http://www.mun.ca/alciato/whit/w166b.html

Also, this medallion by Hilliard:

Nicholas Hilliard Gold medallion, Elizabeth I (BM), about 1580-90

The Drake Jewel also has the Phoenix, a common symbol associated with Elizabeth representing rebirth and continuity and the fact that there is only ever one phoenix alive at one time. It is also connected with virginal purity and purity in religion.

Page from Geoffrey Witney, A Choice of Emblems (1586), Unica Semper Avis (Only One Bird of its Kind)

But note the symbols mean different things, here Whitney refers to his home town of Nampwiche and renewal.

The Phoenix rare, with fethers freshe of hewe,

ARABIAS righte, and sacred to the Sonne:

Whome, other birdes with wonder seeme to vewe,

Dothe live untill a thousande yeares bee ronne: Then makes a pile: which, when with Sonne it burnes, Shee flies therein, and so to ashes turnes.

Whereof, behoulde, an other Phoenix rare,

With speede dothe rise most beautifull and faire:

And thoughe for truthe, this manie doe declare,

Yet thereunto, I meane not for to sweare: Althoughe I knowe that Aucthors witnes true, What here I write, bothe of the oulde, and newe.

Which when I wayed, the newe, and eke the oulde,

I thought uppon your towne destroyed with fire:

And did in minde, the newe NAMPWICHE behoulde,

A spectacle for anie mans desire: Whose buildinges brave, where cinders weare but late, Did represente (me thought) the Phoenix fate.

And as the oulde, was manie hundreth yeares,

A towne of fame, before it felt that crosse:

Even so, (I hope) this WICHE, that nowe appeares,

A Phoenix age shall laste, and knowe no losse: Which GOD vouchsafe, who make you thankfull, all: That see this rise, and sawe the other fall.

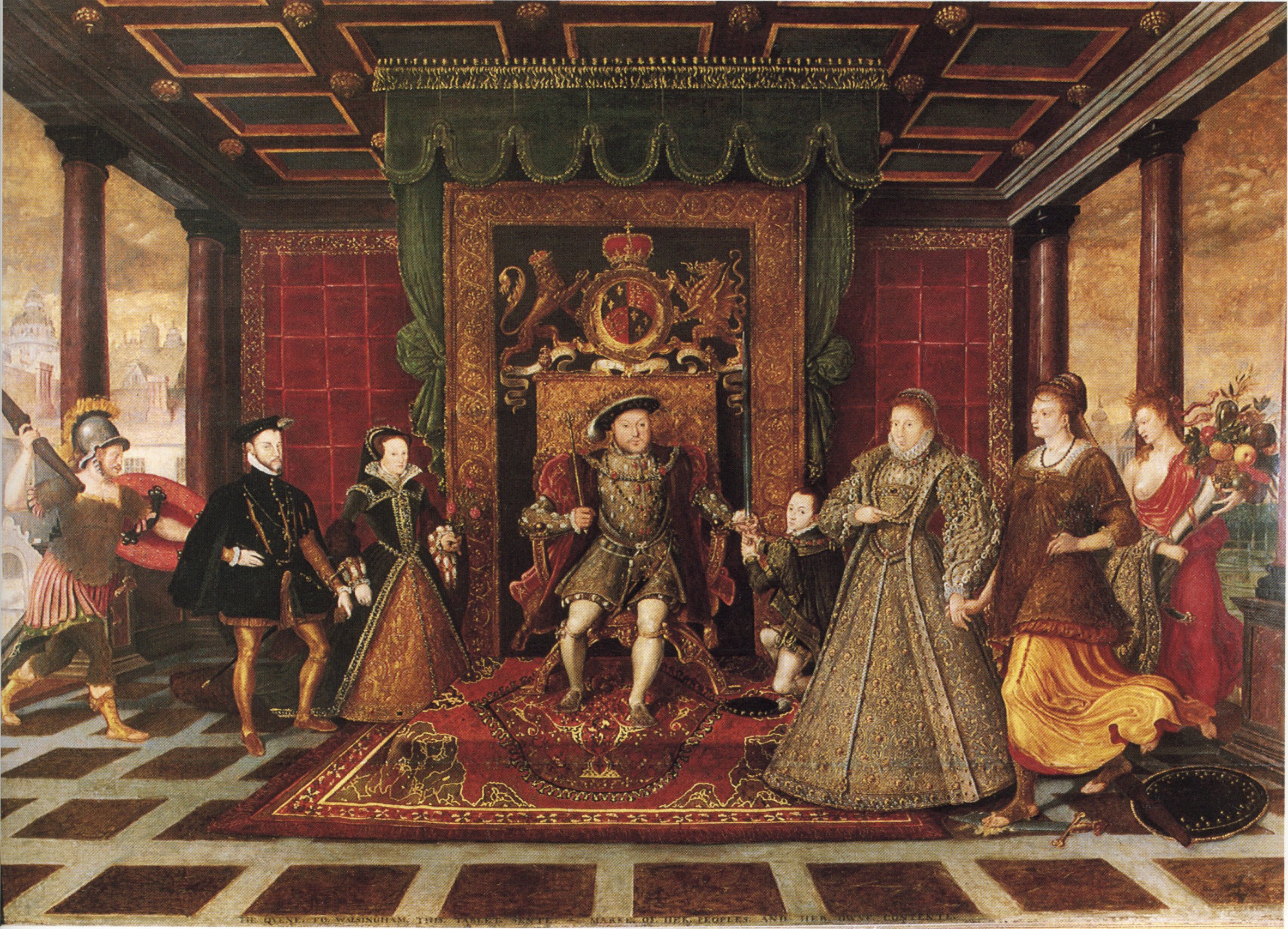

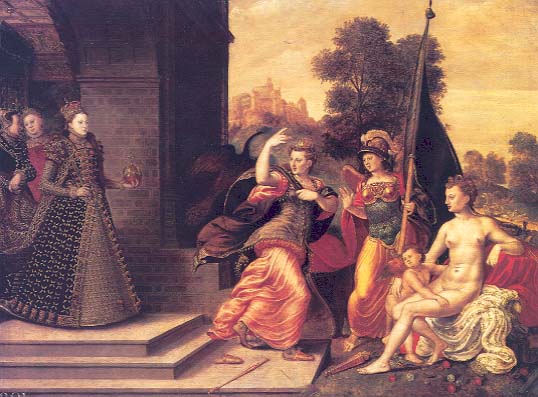

‘HE’, Elizabeth and the Three Goddesses (Royal Collection), 1569

Already discussed but included for reference. Note that it is often attributed to Hans Eworth as it is signed ‘HE’ although the letters are sloping unlike his normal signature.

Sieve Portraits

Quentin Massys the Younger, Sieve Portrait (Siena), 1583

It was cleaned in the 1980s and the signature of Quentin Massys discovered on the globe. He was a Netherlandish artist and there is no evidence he came to England. The face is like the Darnley Portrait so it may have been copied from an engraving. Sir Christopher Hatton was the patron and the man n yellow tights in the background has Hatton’s symbol of a hind on his sleeve. The sieve symbol goes back to Petrach’s story of the Vestal Virgin Tuccia who carried water from the Tiber in a sieve to prove her innocence and virginity. It is therefore a symbol of virginity with classical allusions. The Italian inscription on the sieve can be translated “The good falls to the ground while the bad remains in the saddle” so it also shows Elizabeth’s wisdom and ability to discriminate the good from the bad.

The column is covered in medallions showing the story of Dido and Aeneas from engravings by Mark Antonio Ramondi. The story is how Dido and Aeneas fall in love but Aeneas has to leave her to go off and found Rome.

The other inscription reads “Wearied rest and rested weariness” also from Petrach and the Vestal Virgins.

Sir Christopher Hatton’s hind suggests he commissioned it. It was produced during the marriage negotiations with Henry Duke of Anjou and Hatton was against marriage to a foreign Catholic and he decided it was better to have a Virgin Queen than a Catholic Queen. Like Aeneas the Queen had to leave her ‘love’ to found an Empire. Hatton believed England should build up its navy and found an Empire around the world, we can see on the globe ships setting out from England.

In the sixteenth century the state of virginity has very negative connotations and people were almost embarrassed by it as it was associated with failure and old maids. So this portrait is trying to create a new set of positive associations around the idea of a Virgin Queen.

All the sieve portraits date from 1579-83, the time of the Anjou marriage negotiations.

The portrait can be seen as a piece of lobbying by Hatton so we have a portrait of Elizabeth being used as part of a political campaign by an individual. This is interesting as most writers about the political significance of Elizabeth’s portraits tend to assume that it is always the government or court using the portraits to convey a state message. In this case it is an individual lobbying.

Hilliard, Elizabeth I, The Ermine Portrait, 1585

Anon, Allegory of the Tudor Succession (Sudeley Castle), c. 1572

Inscription on the frame of the Allegory of the Tudor Succession (Sudeley Castle), c.1572:

The Queen to [Sir Francis] Walsingham this tablet sent Mark of her people s and her own content.

Usually attributed to Lucas de Heere (pronounced ‘Hearer’). Elizabeth is bring Peace and Plenty while Mary and Philip are bringing in Mars the god of war.

It was issued as a print. The “Allegory of the Tudor Succession” at Yale, c. 1590s, is based on the print and the fashions have been updated from the 1570s to the 1590s.

Hilliard, Heneage Jewel (V&A), c.1600

Mask of Youth

This is a good description that I thought was invented by Roy Strong to describe her late portraits but a knowledgeable user of the site has pointed out that the usage was coined by Neville Williams in 1972, 27 years before Roy Strong, in his book, The Life and Times of Elizabeth I (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1972).

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Ditchley Portrait (NPG), c. 1592

The Ditchley portrait was commissioned by Sir Henry Lee. Elizabeth may have been asked to decipher its meaning as part of his courtly entertainment.

Elizabeth did exert control over her image in so far as she handed out miniatures of her portrait and she also controlled the images on the coinage and the Great Seal.

Anon, Rainbow Portrait (Hatfield House), c. 1600 (?)

This has been attributed to many artists such as Isaac Oliver (unlikely) and Marcus Gheeraerts but we don’t know. The inscription can be translated “No rainbow without the sun.”

Her courtiers were concerned about succession and Elizabeth did not wish to name her successor for fear of uprising. So her courtiers created the fiction of an eternal, ever youthful queen. We have a description of what she actually looked like:

Queen Elizabeth’s appearance (aged 65) was described in the 1590s by a German visitor (W. Rye, England as Seen by Foreigners (London, 1865), pp.1 04-5).

She was very majestic: her face oblong, fair but wrinkled; her eyes small, yet black and pleasant; her nose a little hooked, her lips narrow, and her teeth black, (a defect the English seem subject to, from their too great use of sugar); she had in her ears two pearls with very rich drops; her hair was of auburn colour, but false … upon her head she had a small crown … her bosom was uncovered, as all the English ladies have it till they marry; and she had on a necklace of exceeding fine jewels; her hands were slender, her fingers rather long…

George Gower (?), Armada Portrait (private collection), c. 1588

After Gower, Elizabeth I (NPG), c. 1588

Robert Peake, Procession Portrait (Sherborne Castle), c. 1600