Elizabethan Painting

See Tudor and Elizabethan Portraits.

The Elizabethan period picks up from the work of Holbein. The oldest work in the Tate is:

John Bettes, An Unknown Man in a Black Cap, 1545

This is a wooden panel signed on the back twice by John Bettes (Englishman). The blue background has changed to brown and it has been cut on the left and right and probably top and bottom although we don’t know why. John Bettes is mentioned in the Royal accounts as having been paid for a limning portrait of the King and Queen but we know very little about him, we don’t even know if he was trained by Holbein.

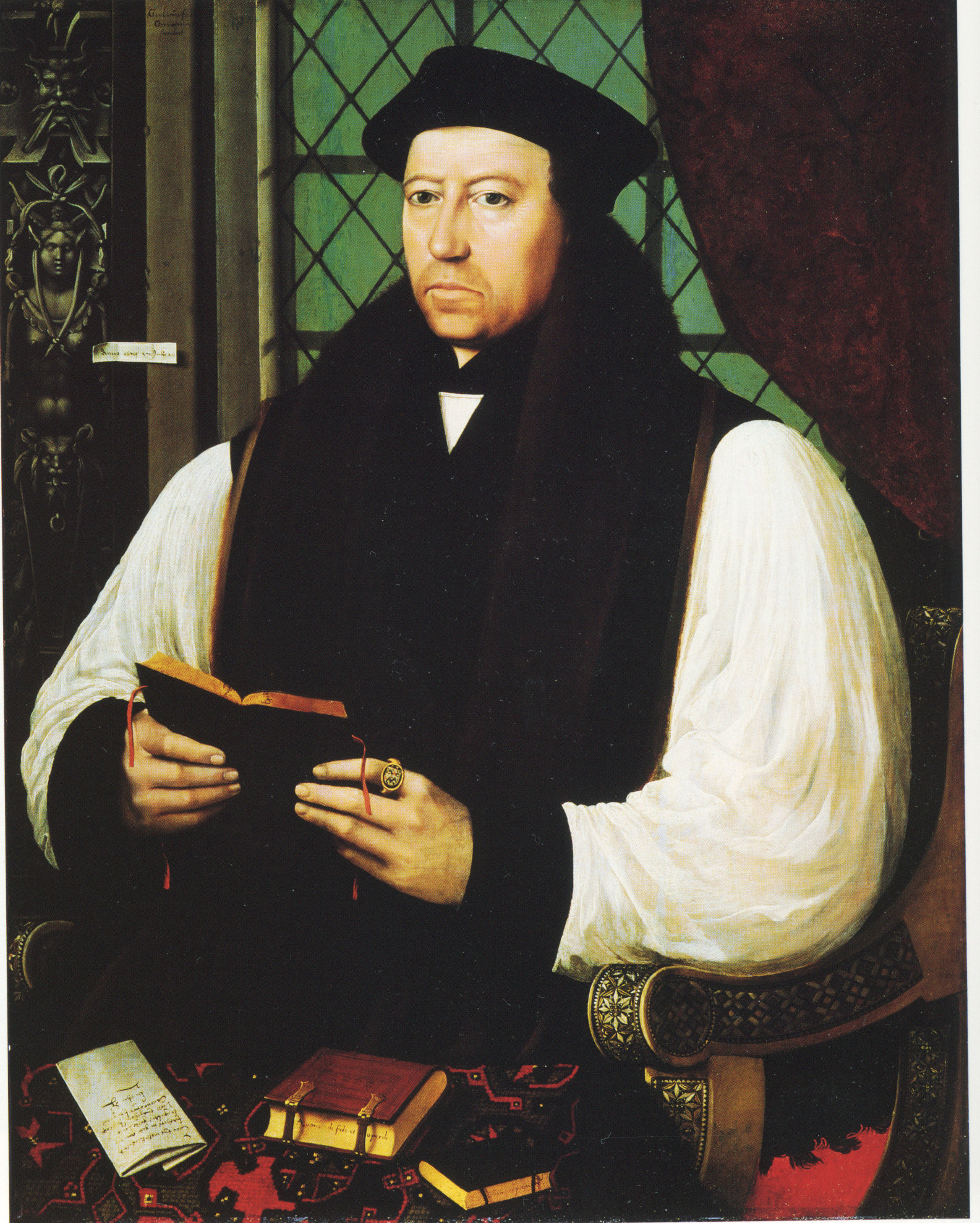

Gerlach Flicke, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, 1545-6

Flicke is also reminiscent of Holbein and worked in the 1540s.

William Scrots, Edward VI, 1550

Scrots, a Netherlander, was paid £62 10s a year, an enormous salary as Holbein was only paid £32 a year (but there had been inflation). Scrots had been a painter abroad and had worked for Mary of the Netherlands, and he painted in an international style.

Scrots also painted Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, 1546. The painting is attributed to Scrots or his workshop.

Jacob Seisenegger, Portrait of Emperor Charles V, 1532

Seisenegger was a jobbing painter like Flicke who became significant in the Hapsburg courts. He was from Austria.

Both produced fashionable mid-century portraiture that was:

- Full length, often life-size (The Ambassadors was also an early example)

- Three-quarter turn, contraposto style

- Rich curtains that show off rich materials, silks and satins.

Compare Titian’s portrait of Charles V, a copy of Seisenegger!

Titian, Portrait of Charles V, 1533

This portrait established a tradition across Europe.

Seissenegger, Georg Fugger, 1541, a famous banking family. This shows how someone of fabulous wealth wanted to display himself, life size, full length, curtain and column.

Scrots disappears after Edward VI dies. Edward is succeeded by Mary who marries Philip II of Spain and so England becomes just another minor Hapsburg court but it does give Mary’s court access to all the Hapsburg court painters across Europe. Antonis Mor (famous for painting Henry Lee) was sent to England to paint Mary Tudor and there are two versions, one in the Prado, one in England so it is possible it was painted as a gift to Philip when he was in Spain.

Antonis Mor, Mary Tudor, 1554, Prado

Mary is holding a flower (not a Tudor rose) as a love token. The painting does not look flattering but we do not know what she looked like. She is presented as a very wealthy woman but there are no signs of the fact that she is Queen of England in her own right. We do not know why, maybe she did not want to appear to confront Philip with her power. It follows the standard Hapsburg format, for example:

Titian, Portrait of Isabella of Portugal, 1548

Note that Titian’s portrait is idealised unlike the more naturalistic Northern European work of Mor. Mary is presented as just another Hapsburg consort.

Anon, Darnley Portrait of Elizabeth I, c1575

Roy Strong suggests this portrait was by Fredirico Zuccaro as we have a drawing by him of Elizabeth (British Museum, 1575). Elizabeth was excommunicated in 1570 so Zuccaro would have had to get special permission to visit England and this is the main evidence Strong has for suggesting it was painted by him.

English Elizabethan Painting

There is a distinct style of English Elizabethan painting that was no adopted in other countries. This does not mean it was the only style used in England but it was one of the main styles between the 1560s and 1580s.

Anon, A Young Lady aged 21, 1569, possibly Helena Snakenborg, Later Marchioness of Northampton.

Compare with the portrait of Mary by Mor:

- No background

- Not naturalistic

- Flat, decorative, patterned, geometric, hieratic, iconic style.

- A statement of their position in society, not trying to represent their personality.

- In raking light the ruff is heavily raised and covered in gold. It is like 15th century Italian altarpieces that build up the elements.

Anon, Cholmondeley Women, c1600. The inscription says that both gave birth on the same day and there are differences between the two, one woman and her baby has blue eyes and the other brown and their ruffs are different. It is assumed it was by a Chester painter as its provenance places it in the area and we know there was an active Painter’s Guild in Chester.

Why did this style of painting develop in England?

Nicholas Hilliard (in R. Thornton & T. Cain (eds), A Treatise Concerning the Arte of Limning by Nicholas Hilliard (1981), pp.85-87):

This makes me to remember the words also reasoning of Her Majesty when first I came in her Highness’s presence to draw; who after showing me how she noted great difference of shadowing in the works, and the diversity of drawers of sundry nations, and that the Italians, who had the name to be the cunningest and to draw best, shadowed not, required of me the reason of it, seeing that best to show oneself needeth no shadow of place, but rather the open light. The which I granted, and affirmed that shadows in pictures were indeed caused by the shadow of the place, or coming in of the light only one way into the place at some small or high window, which many workmen covet to work in for ease to their sight, and to give unto them a grosser line, and a more apparent line to be discerned; and maketh the work emboss well, and show very well afar off, which to limning work needeth not, because it is to be viewed of necessity in hand near unto the eye. Here her Majesty conceived the reason, and therefore chose her place to sit in for the purpose in the open alley of a goodly garden, where no tree was near, nor any shadow at all, save that as the heaven is lighter than the earth, so must there be that little shadow that was from the earth. This Her Majesty’s curious demand hath greatly bettered my judgement, besides divers other like questions in art by her most excellent Majesty, which to speak or write of were fitter for some better clerk.

Roy Strong claims this style of painting was a result of a lack of expertise in England at the time. It is more likely that is was a conscious choice resulting from a court fashion, perhaps resulting from the views of the Queen.

Anon, Elizabeth Coronation Portrait, c1600

This probably a copy of an original 1558 version but we do not know how accurate a copy it is. Note the flatness and love of pattern, if it is an accurate copy it shows how early in her reign this style was adopted. It suggests Byzantine icon painting, full frontal, two-dimensional stylized figures. They were deliberately stylized possibly to prevent them being seen as breaking the Second Commandment concerning graven images and to prevent them being idolized.

It could also have been modelled on the portrait of Richard II which in the 16th century was behind the stalls in Westminster Abbey.

Richard II, Westminster Abbey, c 1394-5

It also reminds us of the Virgin Mary particularly the Misericordia in which she shields people under her cloak (Piero della Francesca, Hans Memling, Jean Miralhet).

Hans Eworth, Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses, 1569. It is signed H.E. suggesting Hans Eworth but there were other artists that could have signed a painting this way. It is a mixture of Italian Mannerist and English styles, note that Elizabeth is painted in the flat style and the goddesses are rounded three-dimensional figures. It is as if the artist came to England from abroad and adopted the English style for the English components of the painting, particularly the representation of Elizabeth. Elizabeth is presented as a solid, stable figure compared to Juno who is ungainly, and is fleeing having lost her slipper.

Henry Peacham, The Compleat Gentleman, 1634

Peacham was the person previously mentioned who was beaten by his schoolmaster for drawing. Although this engraving is 1634 it still follows some Elizabethan traditions. Note that the personification of ‘NOBILITAS’ is face-on and poorly modelled while ‘SCIENTIA’ is a contraposto, classical, modelled nude. Both conventions are shown in one picture which raises the questions about whether there were two conventions for representation each appropriate to its subject. The book is a guide for gentlemen on how to behave.

17th, 18th and 19th and even 20th century commentators like Roy Strong see all English Tudor painting as poorly executed compared to, for example, Leonardo and Raphael. This attitude has only changed in the late 20th century. Perhaps a greater historical awareness and a post-structural attitude that everything is culturally determined has taught us not to judge works of other periods and cultures by our own standards. This of course breaks the long Vasarian tradition that suggests a gradual progress towards naturalism.

Elizabeth might not have been interested in the visual arts although a letter from a Parisian art dealer to Lord Burghley mentions that he heard that Elizabeth was very interested in art. However, this could have been a simple sales pitch. It is also documented that the burghers of Ghent at one stage proposed sending the Ghent altarpiece to England as they had heard of Elizabeth’ interest in art. We are fortunate it was never sent otherwise it could have been destroyed.

Anon, Frances Sidney, Countess of Sussex (Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge), c15C

Sidney was the founder of Sidney Sussex College. Note the too tiny dog whose front paws rest unconvincingly on her dress while its back paws are too far away on the ground. Behind her is a common motive, a large chair with a cushion across the back. She is wearing a long train that has been folded around the front.

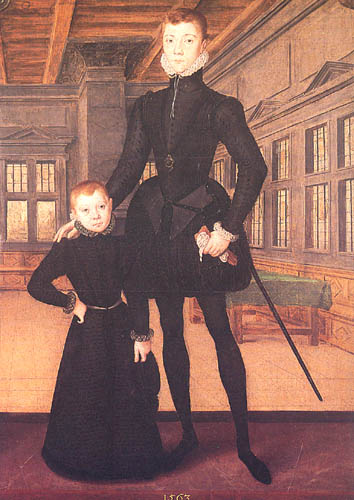

Hans Eworth, Henry Lord Darnley and Charles Stewart (Royal Collection), 1563 (signed).

Two brothers in a convincing interior with linear perspective. After spending years trying to find the house represented we now know it is copied from a Vredeman de Vries print. There is even a blank piece at the bottom of Eworth’s picture corresponding to the bottom of the page of Vrie’s print.

Anon, Lord Edward Russell, 1573

Note the impresa discussed before, the man in a maze and a handful of serpents.

Hans Eworth, Margaret Audley, Duchess of Norfolk, 1562

Invention, pattern and the incorporation of symbolic ideas was appreciated not light and shade.

‘Curious’ Painting

In the 1590s a new style (or what could be regarded as a return to the old style or the acceptance of the foreign style) of painting developed. It developed in both limning and oil painting and one of the leading exponents was Isaac Oliver.

At the same time poets started writing about ‘lifelike’ images as an indication of the most desirable painting. Possibly a reference to the works of classical antiquity when mimetic representation was valued and writers spoke of grapes painted in so lifelike a way they fooled the birds.

John de Critz the Elder, Sir Francis Walsingham, c. 1587

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Captain Thomas Lee, (Tate Britain), 1594

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Earl of Essex (Woburn), c1596

Isaac Oliver, Earl of Essex, c1596

The dashing and up-to-date Earl of Essex dropped the dated look of Nicholas Hilliard and adopted the new trendy look of Isaac Oliver.