Art and Architecture at the Tudor Court

Before the Elizabethan period buildings were added to incrementally and built around an inner courtyard. Because they were built incrementally they were very complex.

We must also remember that the term ‘architect’ was not used or was used rarely and then not in the modern sense. One famous figure was Dr. John Dee, scientist and astrologer who in the forward to his translation of Euclid in 1570 quotes Vitruvius and Alberti.

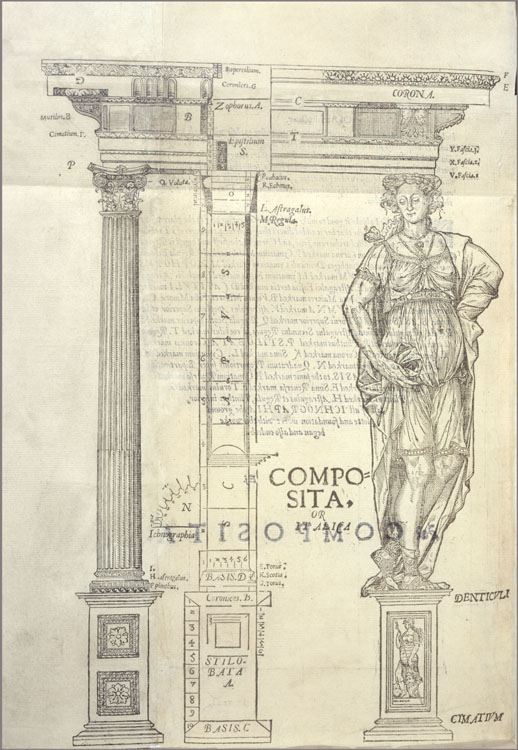

John Shute was sent to Italy in the 1550s by his patron Protector Somerset. When he returned Mary was on the throne but he eventually published his book in 1563.

Page from John Shute, The First and Chief Groundes of Architecture (1563)

John Shute describes himself as paynter and architect and he was a member of the Painters’ and Stainers’ Guild. There is no evidence however that he actually built anything. His book is the first book of architecture in English but it is derived from Vitruvius and Serlio.

Elizabethan houses were often built from scratch rather than as modified monasteries and there was a building book during Elizabeth’s reign (although she built anything herself).

Who designed Elizabethan courtier houses? The patron had a big say if they were interested in building otherwise it was the surveyor, a person sometimes brought in to oversee the building project, or the master mason who sometimes was responsible for the project. Some master masons were in charge of the project and did not actually cut stone themselves.

For example, Sir Thomas Tresham was mad about building and all the designs were his. Henry VIII is credited with the device for some buildings but it is unlikely he sat down and drew the plans, he may have had the idea for the device.

Not many plans (then called plattes) or elevations (then called uprights) survive.

Robert Smythson, designs for Wollaton Hall including a drawing of a corner tower (RIBA), c. 1580s.

As mentioned above Elizabeth built very little, perhaps some fortifications on the south coast. At Hampton Court she put in a bay window, her contribution to Elizabethan architectural advance. Her Office of Works was responsible for the maintenance of her many palaces.

There were builders and ‘architects’ outside London, William Arnold, for example was responsible for the design of many buildings in the South-West including the impressive Montacute House.

Designing houses was not a full-time profession and Robert Smythson, for example, was a rent collector for Sir Francis Willoughby.

Painting was generally considered of low status, too lowly for a gentleman, in Elizabeth’s reign but designing buildings was different. For example, William

Cecil was sent an elevation of a lodge in 1577 for his opinion. Why was building

design regarded as more worthy of a gentleman than painting?

- It was less messy and there was more intellectual thought involved.

- There was much more money involved in building, they were major investments.

- A building was created to carry your families reputation for the current and future generation.

- Many of the rich were newly rich lawyers who were creating dynasties that they thought would last hundreds of years and a building would survive that long.

- Architecture was related to the liberal arts of mathematics, geometry and they related skill of perspective, which were taught to gentlemen.

- The raised expectations for education meant that more people could appreciate a well designed building.

- A magnificent building would impress the monarch, source of all power.

- Vitruvius was a known classical text and he wrote about architecture so the subject had respectability.

- The role of the gentleman knight was to wage war and an essential skill was the ability to design fortifications and military buildings.

- A magnificent building enabled one gentleman to outdo another rival and perhaps as a result receive a visit from the monarch instead of them.

- Strictly speaking architecture, like painting was a mechanical art but there was more of a case that it should be regarded as a liberal art.

Lord Burghley (William Cecil, 1520-1598) and his son

Robert Cecil (later 1st Earl of Salisbury, 1563-1612) had a collection of drawings, two plans of Longleat, a plan of the Escorial, Spain (surprisingly), a plan of buildings designed as circles, triangles and crosses, so it was fashionable.

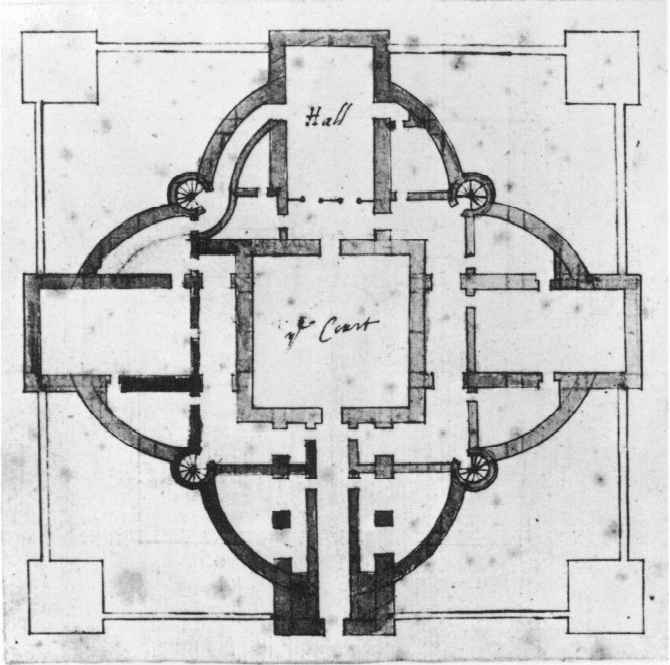

Smythson, plan for a house Greek Cross (a device)

The design of a building became complex but the fixtures and fittings were not regarded as part of the overall design at this period and were left to the building contractor although sometimes a specialist craftsman was brought in or the carving was imported.

Alan Maynard, a French sculptor, fireplace at Longleat House (Wiltshire)

Stonework could be imported from Antwerp, for example, Burghley House. Some parts, such as wood panelling could be made in London and carried to the site but plasterwork had to be made locally. We don’t know if local craftsmen knew about international styles and what was being done in other grand houses. They could have found out from:

- Pattern books (although we don’t know if a craftsman would own a pattern book of if the were owned by the patron).

- Prints.

- Itinerant craftsmen (carpenters and masons) who could have come from a Royal Works (the cream of craftsmen) and so would know of foreign styles.

- Sketches made while travelling around.

Sebastiano Serlio, Fireplace design in Architectura

Fireplace at Wollaton Hall (Notts), c. 1580-88

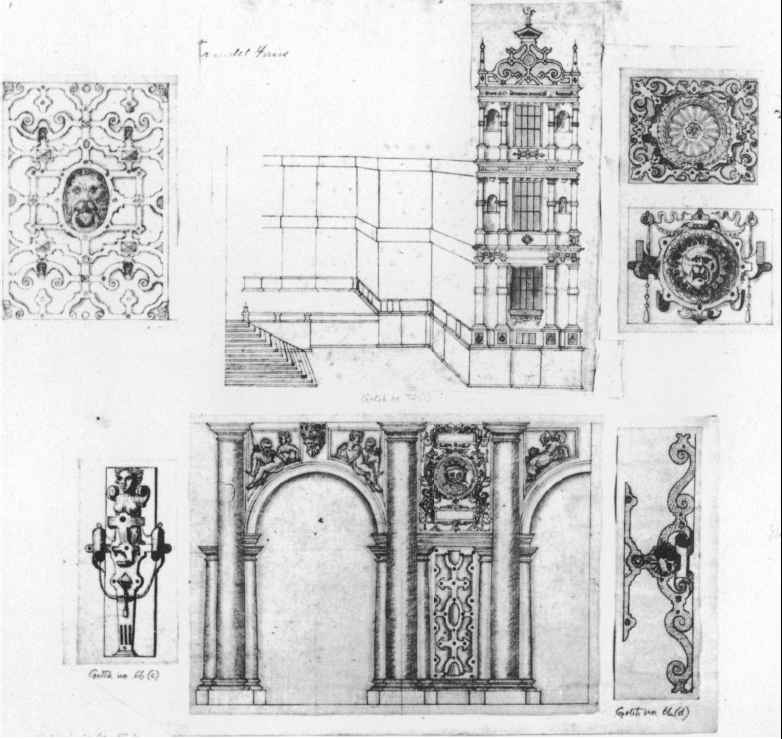

Page from Vredeman de Vries, Variae Architecturae Formae (1563). THis was

used in the stone screen in the great hall at Wollaton.

Hall Screen at Wollaton Hall (Nott’s)

This was also true of Burghley House, Hardwick Hall and so on, they all used designs from John Shute, Vredeman de Vries, Serlio and so on. Libraries at the time included books by Serlio, Shute, Vredeman de Vries and Tresham also had Palladio and Alberti.

Elizabethan Periods

The designs for Elizabethan courtier houses are difficult to divide into periods as they overlap. They all incorporated devices and symbolism by can roughly be divided into:

- Phase 1: up to 1570, some classical features, not symmetrical, inward looking, e.g. Burghley House courtyard

- Phase 2: 1570-1580, symmetrical, e.g. Kirby Hall, Longleat

- Phase 3: 1580s and 1590s, return to medieval, e.g. Burghley west front

Phase 1 up to 1570

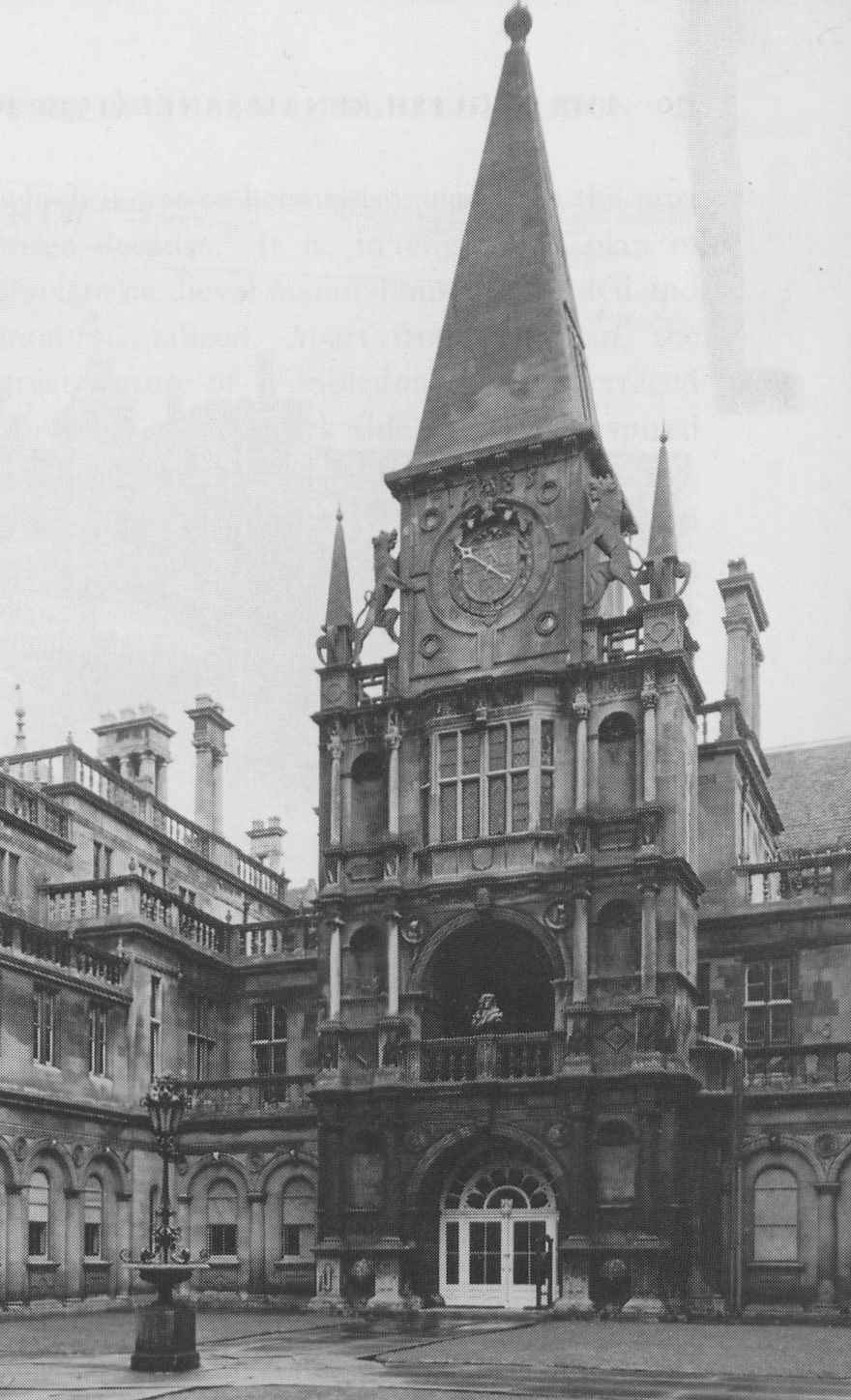

Courtyard of Burghley House (Lincolnshire), c. 1560s

A courtyard house which originally had an open loggia at the bottom which was filled in in the 18th century. Ignore the clock as it is 1583 and the structure in which the clock is mounted, below this it is 1560s. It was influenced by Somerset House, John Thorpe:

John Thorpe, drawing of Somerset House

Somerset House had an enormous and enduring influence. Protector Somerset’s secretary was William Cecil (later Lord Burghley) and many of Somerset’s retinue went on to achieve high positions and build large houses.

The loggia was brought from Antwerp in the 1560s by William Cecil and it has a French influence which was common at this period. Later an Italian influence would also been seen.

The interior at Burghley House was very elaborate in the French classical style, as can be seen by this stairway:

Stone stair at Burghley House, stone carved in great detail.

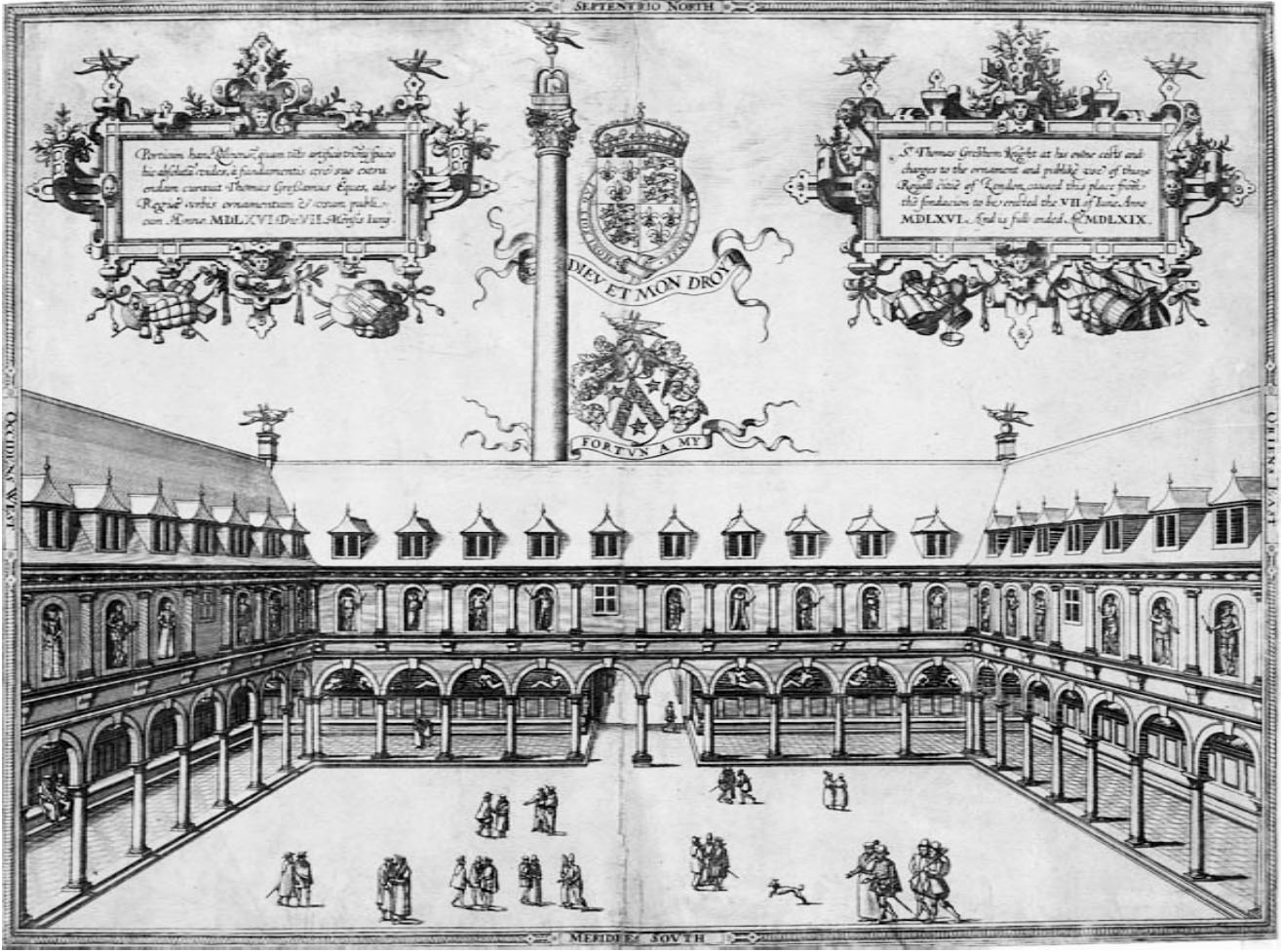

Frans Hogenberg, The Royal Exchange (engraving), c. 1569

The Royal Exchange was destroyed by fire in 1666. It had an open loggia like Burghley House and it was also shipped from Antwerp as were all the statues of kings and queens and the ornamental work. It was built for Sir Thomas Gresham whose device was a grasshopper.

Phase 2 1570-80

This period is more precise, classical correctness and it followed the classical rules and had a greater sense of proportion.

Kirby Hall (Northamptonshire), 1570-73

Had double height pilasters, called a giant order. The broken pediment may be 17th century. Note the symmetry of the left and right even though the left is two separate floors and the right is one great hall.

There are pilasters either side of one of the doors at Kirby that are copied from the title page of John Shute’s book. It is as if the craftsman could not even by troubled to open the book and just copied the title page design. In Italy this would never happen, the books were regarded as a source of ideas.

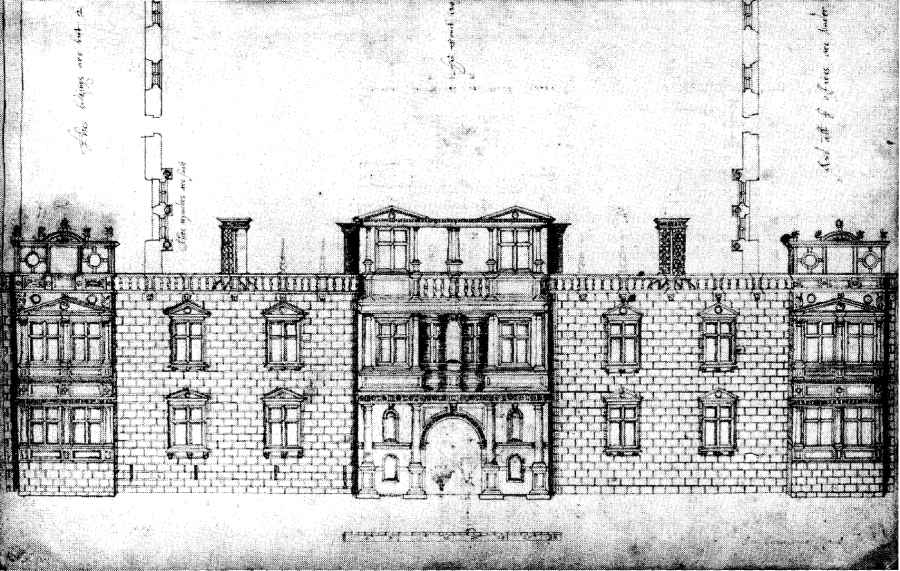

Longleat House (Wiltshire), 1572-80

Longleat is an uniquely documented building that was constructed in four separate phases and today we see the final fourth phase. The first phase was 1547 and was a crude conversion of a monastery, the second phase burned down, the third phase was regarded as unsatisfactory and the fourth phase added a symmetrical outer skin. It was built for Sir John Thynne who was the Steward overseeing the construction of Somerset House. We have the accounts and many letters concerning the house between Sir John Thynne and the craftsmen. He was a perfectionist and ordered one window to be pulled down and rebuilt as it was not perfect.

John Thorpe, drawing of Somerset House

Compare Longleat with Somerset House. Both have an Italianate balustrade, bay windows (loved by Elizabethans) and paired windows. Note the windows do not go to the end of the building as they do in France. Longleat doesn’t have a central entrance into a courtyard but has a raised door leading into the house. Longleat has aprons below the windows which incorporate roundels in the upper apron above the string course. Both have decorated rooflines. The Somerset House windows look as if they are floating around but the Longleat windows are strongly fixed by the clear horizontal string course and the decorated aprons. Longleat has a banqueting house on the roof and the balustrade will have assisted walking on the roof.

The Longleat garden and house were designed together and the house looks out onto the garden and the house is designed to be viewed from the garden. Somerset House like Hampton Court and Nonsuch Palace was inward looking, the major rooms like the King’s apartment at Hampton Court look into the inner courtyard which at Nonsuch was the most highly decorated.

The Great Hall at Longleat has a screen passage but the hall cannot be seen from the outside, all the rooms are made symmetrical so symmetry is now more important than hierarchy. Longleat also has a private chapel but this also cannot be distinguished from the outside. The little courtyards on the inside at Longleat arise from the original monastery foundations and are need to bring light to the inner rooms. There is not even a door marked on the original plan into the inner courtyard, it is simply a light well.

Longleat is an outward looking building unlike Somerset House which is an inward looking building.

(Phase 2.5)

This is a later development of Phase 2 which is a shift to Flemish Mannerism but still classical.

Vredeman de Vries, design for gables.

Note the strapwork on the gables, this became very fashionable as did the design ideas from Vredeman de Vries.

Wollaton Hall is one of the most spectacular example of this later Phase 2 building style. It is attributed to Robert Smythson who also worked at Longleat. It was finished in 1588 and the patron Sir Francis Willoughby was fascinated by architecture. This building uses the corners and demonstrates ‘massing’, .i.e elements that project forward to articulate the building. In this case there are

two steps forward from the line of the entrance. It is much more vertical than Longleat and there is the suggestion of a castle with turrets (see Phase 3). The hall is unusual in that it is placed in the centre like a filled in courtyard. Above the ceiling of the two storey Great Hall there is what we believe is a prospect room, a room used to view the garden but unusually it does not have a fireplace. The hammerbeam rook of the Great Hall is fake, unlike Hampton Court, in that it does not support the self-supporting ceiling but hangs from it.

Phase 3: 1580s and 90s

Strangely, towards the end of Elizabeth’s reign courtiers houses started to look back towards medieval houses.

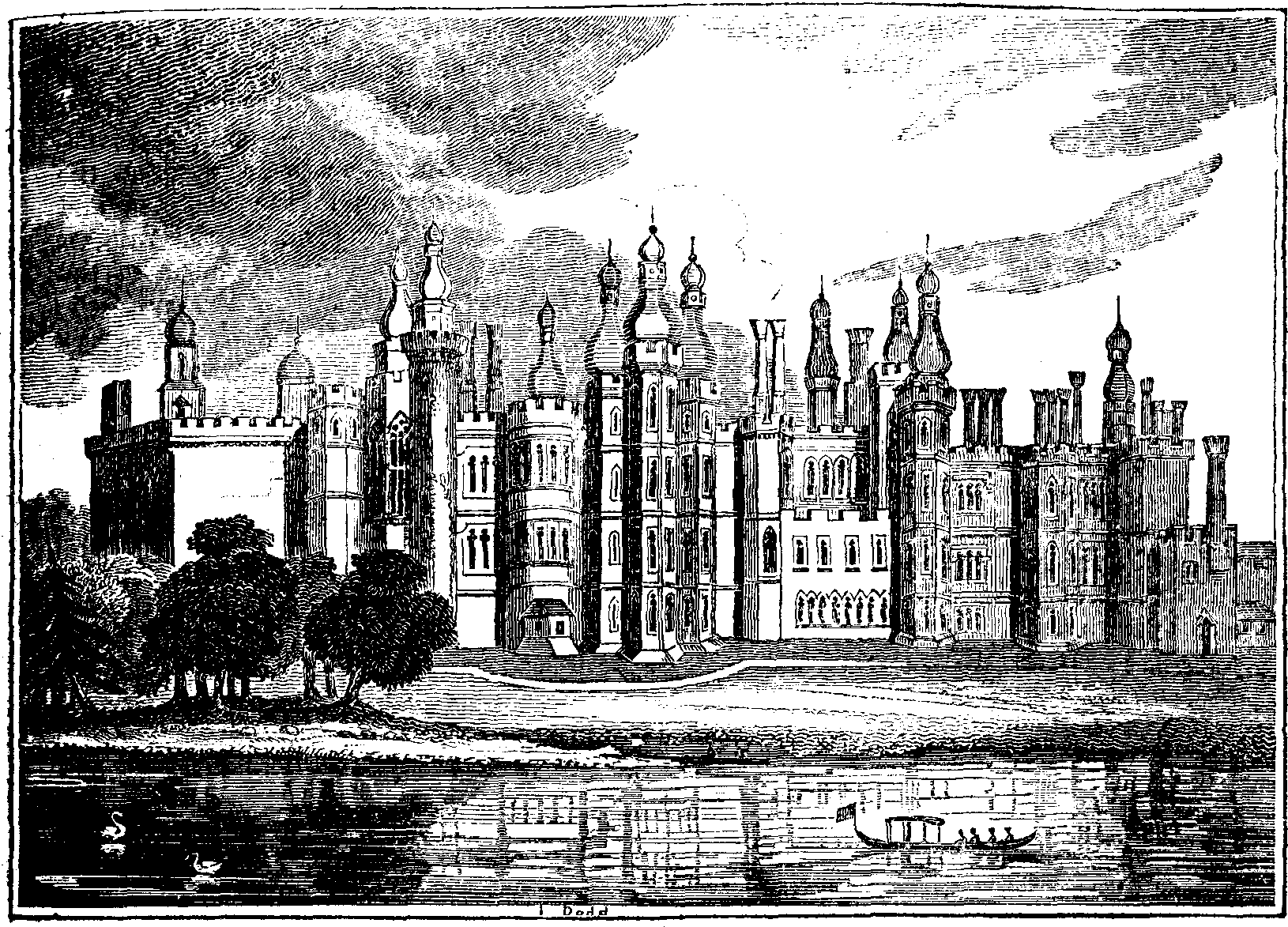

West front of Burghley House, c. 1580s

The west facade of Burghley was built in the 1580s and has a structure like a gate house tower entrance that could have been built a 100 years earlier and bears some comparison with the gatehouse of Hampton Court. It is an example of neo-medievalism, a style that reappears on may occasions through English history.

It looks like Hengrave Hall, which was built in 1525.

Or even Richmond Palace built in the reign of Henry VII.

Hollar, View of Richmond Palace (engraving), 17th century

Burghley south front has a large Great Hal visible, again going back 100 years, and it also has a fake hammerbeam roof. Mark Girouard found that the hall was rebuilt in the 1580s/90s to make it much larger and one wonders why? Is it related to William Cecil becoming Lord Burghley and wanting to create the impression of medieval ancestry? Or was he just getting old and more conservative?