Description by Lupold von Wedel of the Accession Day tilt in 1584 (‘Journey through England and Scotland made by Lupold von Wedel in the years 1584 and 1585’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series IX (1895), pp.258-9):

Now approached the day, when on November 17 the tournament was to be held… About twelve o clock the queen and her ladies placed themselves at the windows in a long room at Weithol [Whitehall] palace, near Westminster, opposite the barrier where the tournament was to be held. From this room a broad staircase led downwards, and round the barrier stands were arranged by boards above the ground, so that everybody by paying 12d. would get a stand and see the play… Many thousand spectators, men, women and girls, got places, not to speak of those who were within the barrier and paid nothing.

During the whole time of the tournament all those who wished to fight entered the list by pairs, the trumpets being blown at the time and other musical instruments. The combatants had their servants clad in different colours, they, however, did not enter the barrier, but arranged themselves on both sides. Some of the servants were disguised like savages, or like Irishmen, with the hair hanging down to the girdle like women, others had horses equipped like elephants, some carriages were drawn by men, others appeared to move by themselves; altogether the carriages were very odd in appearance. Some gentlemen had their horses with them and mounted in full armour directly from the carriage. There were some who showed very good horsemanship and were also in fine attire. The manner of the combat each had settled before entering the lists. The costs amounted to several thousand pounds each.

When a gentleman with his servants approached the barrier, on horseback or in a carriage, he stopped at the foot of the staircase leading to the queen s room, while one of his servants in pompous attire of a special pattern mounted the steps and addressed the queen in well-composed verses or with a ludicrous speech, making her and her ladies laugh. When the speech was ended he in the name of his lord offered to the queen a costly present.. .Now always two by two rode against each other, breaking lances across the beam.. . The fête lasted until five o’clock in the afternoon…

This was written by someone was was there who was looking at it as an outsider, a foreign visitor. We are not certain when the Accession Day tilts started but is likely that it was in the mid to late 1570s. Each year the event grew until it became the major festival of the year in the 1580s and particularly the 1590s. It was a festival not just for the court but as the above makes clear for anyone who paid a shilling or even anyone who could squeeze in “within the barrier”.

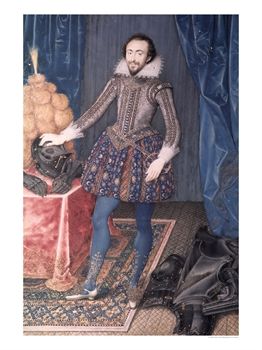

Isaac Oliver, Edward Herbert, 1st Baron Herbert of Cherbury, 1610-4

Edward Herbert is wearing his Accession Day costume and his tilt armour is with his squire is in the background. The casual pose, the babbling brook, the greenwood, the untied laces round his collar all indicate he is melancholic. There are many portraits of courtiers in their tilt costume so they were clearly very proud of them and they cost a small fortune. For example,

Isaac Oliver, Portrait of Richard Sackville, 3rd Earl of Dorset, 1616

Even though it is out of the period it indicates the type of costume worn in the 1590s.

Hilliard, Earl of Cumberland, 1590, cabinet miniature, National Maritime Museum, not usually on view unfortunately.

A very important painting showing the costume at the famous 1590 Accession Day tilt when Sir Henry Lee retired as the Queen’s Champion and Cumberland took over. Note the topographic view in the background, unusual in Tudor paintings. It shows the tiltyard at Whitehall, now Horseguard’s Parade. Cumberland has armillary spheres on his sleeve. The armillary sphere was the most sophisticated scientific device available for use as a navigational aid so it was a symbol of learning that suggests the celestial sphere, the universe, overseas discovery and empire.

The tilt was a formal, stylized event for the very rich, a bit like polo today. It was dangerous but was not a combat intended to injure or kill, injuries were due to accidents such as being knocked off a horse. Henry II of France died in 1559 because he had left his visor open and a wooden splinter went through his eye into his brain.The lances were made of light wood that splintered easily to avoid knocking the other person off their horse and injuring them. The winner was the person with the most broken lances. We still have a scorecard showing the number of broken lances for the contestants. The tilt was an anachronism in Elizabethan times as it was a revival of medieval jousting. Such revivals took place throughout the medieval period and only died out in the early seventeenth century.

Cumberland has Elizabeth’s glove on his hat and a pasteboard shield with his impresa (pronounced ‘im-pray-sa’). These shields were placed in the Shield Gallery at Whitehall after the tilt so that visitors could discuss the meaning of the image and motto. This one has the motto ‘Hasta Quan’ meaning ‘When the spear’ suggesting that he will use his lance to defend the Queen until the image comes about. The image shows the Sun, Earth and Moon aligned suggesting this both a solar and lunar eclipse at the same time, that is it will never occur so he will defend her until the end of time. He is wearing a smock over his armour which was removed before the joust. He also had a real shield that was used during the joust.

There was an Armourer’s Company in London in the fourteenth century but nobles often purchased from Milan, Augsburg and Nuremberg. In 1511 Henry VII set up a workshop in London using armourers from Milan, Brussels and later Germany (Almain). Royal armour achieved a style of its own of English simplicity and solidity. Most of our knowledge comes from a book of pen and watercolour drawings called the Almain Armourer’s Album (V&A).

The Armour of George Clifford, Earl of Cumberland (1558-1605; Earl, 1570) by Jacob Halder, Greenwich, circa 1590, Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is amazing it has survived. This type of armour is actually quite thin and light as it was for show and jousting rather than battle.

We have an Inigo Jones drawing of a horse disguised as an elephant, 1610, as was done as part of the entertainment at a tilt.

There is also a painting by Primaticcio of Jean de Dinteville c. 1545 (one of the two in the Ambassadors) showing his armour and impresa in France. His lance is shown through a mock dragon’s head indicating he represents St. George. Jousting was a popular sport throughout Europe and similar rules were followed.

Why Were Tilts Performed?

- They demonstrated magnificence, and Elizabeth carefully organised it so her magnificence was demonstrated by the Accession Day tilts which were paid for by the courtiers performing. It gave Elizabeth and the court a chance to see who was up and coming. The Earl of Essex, an athletic youth, was first seen at a tilt and rose through the court because of his good looks, it is a pity his political acumen did not match his looks.

- It was also a good way for those out of favour with the court to make amends. Sir Robert Cary had got married without permission and was banned from court so in 1593 he attended the tilt in disguise as the forsaken knight who avows solitariness and at the end he revealed himself and the Queen forgave him. He was even able to blame the Queen for his not seeking permission to marry as the Queen had not advanced him enough at court, He could not normally have criticized the Queen but emblematically at the tilt it was permitted.

- Diplomatically the Accession Day tilt showed the wealth of the court to foreign ambassadors and even to the public so common people were able to take pride in the magnificence of the court.

- The jousting also alludes to the fitness and military prowess of the court.

- It demonstrates the unity of the court and the loyalty of the public. In France there were appalling factional differences between the nobles including religious antagonism.

- It was a way for young bloods to let off steam or challenge a rival to a friendly or not so friendly joust.

- It was useful for the courtiers taking part as it was part of a formal dialogue between monarch and subject that gave a format for the Queen to issue orders. Elizabeth was a woman and a monarch and in the 1th century the two were incompatible and it was generally thought the combination would lead to disaster. In Henry’s reign a courtier was told what to do by Henry and just did it. When Elizabeth came to the throne she was only 25, a young woman who had to give orders to her often elderly advisors. The court therefore adopted the ancient rituals of courtly love which established a relationship that enabled Elizabeth to give orders which were accepted by her loving chivalric knight. A knight who worshipped a lady from afar was obliged to carry out any instructions she asked him to perform, even to die for her. One bizarre alternative was used by Christina, Queen of Sweden (1626-1689), who was brought up as a prince, often dressed as a man, and when young was known as “Girl King”.

The mediaevalism of Accession day tilts is shown in other art forms such as medals, coins, badges, poetry and even architecture. Edmund Spenser The Fairie Queen (1595) is about chivalry and medieval times and gives us some oblique insight into the Accession day thinking.

Sir Philip Sidney’s poem Arcadia (1593, first version) refers to the Accession Day tilts. There were many examples of witty presentations, such as the frozen knight in ice, the flaming knight.

Lulworth Castle, 1609, shows the medieval revival in architecture. Although it is 1609 it reflects the thinking of the late Elizabethan period. It could almost be 14th century except for the large windows which would hardly keep out a siege.

In the 1590s the succession problem loomed large as Elizabeth was marriage and refused to name a successor. The defeat of the Armada kept her popular and the chivalric tradition of the Accession Day was an opportunity to show loyalty to the monarch.

Portraits of Elizabeth also refer indirectly to the chivalric code.

Metsys, Elizabeth I The Sieve Portrait, c1583

The image of Elizabeth with a sieve could have different meanings. The most likely is that it refers to the Vestal Virgin, Tuccia, who carried water from the Tiber without spilling a drop to demonstrate her intactness.

The sieve has an inscription which suggests it could also mean separating the wheat from the chaff, that is she is a discriminating ruler.

Andrea Mantegna (1430/1-1506), The Vestal Virgin Tuccia with a sieve, 1495-1506, National Gallery.

Nicholas Hilliard, Elizabeth I, The Ermine Portrait, 1585

Robert Peake, Procession Day Portrait, c1600

This picture evokes a Royal Progress (although we do not know in detail what it shows we can identity most of the people in it, for example, the Third Earl of Cumberland is third from the left).

A Royal Progress

It had its uses as a PR exercise as most people never saw the monarch. Bestowing a favour through Elizabeth deciding who to visit. This was a very important issue to perhaps two rival nobles in a county. It also threw the courtiers together in a way that did not happen in London.

Sir Henry Lee entertained the Queen at Ditchley in Oxfordshire in 1592. For the text see E.K. Chambers, Sir Henry Lee. An Elizabethan Portrait (Oxford, 1936), pp.276-297. Lee in the guise of Loricus an old knight had fallen under an enchanted spell of sleep that only the Queen could break:

[The Queen is then led to a hail, hung with allegorical pictures, where an old Knight lies sleeping, watched by his page.] The page …

Lo here the matter of his [the knight s] ouerthrow thos charmed pictures on the wall depending what was his error yet I maye not knowe but suer it was the fayrie quenes offending & well I tmst it shortly shall haue endinge for neuer was ther man that prince displeased who might not by a prince agayne be eased

Drawe nere & take a yew of euerie table in them no doubte some secreats are concealed wich if you will (for who denies you able) Cannot but by your wisdom be reuealed, So hapely my Mr may be healed. And you so highly of the godes regarded Shall for your speciall vertue be rewarded.

[As the Queen looks at the pictures and divines their meaning, the Knight wakes, and it is to be supposed that the enchantment of the grove is dispelled.. ]

The Page bringeth tydings of his Maister s Recouerie. …May it therefor please you to heare of his life who lyues by you, & woulde not hue but to please you; in whom the sole vertue of your sacred presence, which hath made the weather fayre, & the ground fruitful! at this progresse, wrought so strange an effect and so speedie an alteration…

The Queen went into an enchanted grove where she had to solve riddles to wake the sleeping knight. One such device could have been the Ditchley Portrait.

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Elizabeth I, The Ditchley Portrait, c1592. She is shown commanding the elements and towering into space.

Elizabeth visited Kenilworth where she stayed for 18 days. The theme mixed medieval Arthurian legend with mythological Hercules.

As part of her royal progress of 1575 Elizabeth was entertained by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester at Kenilworth Castle. An account of the visit was printed within 6 months of the visit: George Gascoigne, Princely Pleasures at the Courte at Kenelwoorth. That is to saye, The Copies of all such Verses, Proses, or poetical inventions, and other Devices of Pleasure, as were there devised, and presented by sundry Gentlemen, before the Queen’s Majestie (Printed in John Nichols, Progresses of Queen Elizabeth (1823), vol.1, pp.485-5Z3).

[As the queen approached Kenilworth Castle she was met by a sibyl who recited a lengthy welcome.]

Her Majesty passing on to the first gate, there stode, in the leads and battlements thereof, sixe trumpetters hugelie advaunced, much exceeding the common stature of men in this age, who had likewise huge and monstrous trumpettes counterfetted, wherein they seemed to sound: and behind them were placed certaine trumpetters, who sounded indeede at her Majestie s entrie. And by this clum shew it was ment, that in the daies and reigne of King Arthur, men were of that stature; so that the Castle of Kenelworth should seeme still to be kept by Arthur s heires and their servants.

When her Majesty was entred the gate, and come into the base court, there came unto her a Ladie attended by two Nimphes who came all over the Poole, being so conveyed, that it seemed shee had gone upon water. This Ladie named herselfe the Ladle of the Lake, who spake to her Highness as followeth:

…I am the Lady of this pleasant lake, Who, since the time of the great Arthure s reigne, That here with royal Court abode did make, Have led a lowring life in restless paine, Till now, that this your THIRD arrival here, Doth cause me come abroad, and boldly thus appeare.

For after him such stormes this Castle shooke, By swarming Saxons first who scourgde this land, As foorth of this my Poole I neer durst looke. Though Kenelme King of Merce did take in hand (As sorrowing to see it in deface) To reare these ruines up, and fortifie this place.

…Wherefore I wil attend while you lodge here, (Most peeless Queene) to Court to make resort; And as my love to Arthure dyd appeere, So shal t to you in earnest and in sport. Passe on, Madame, you need no longer stand; The Lake, the Lodge, the Lord, are yours for you to command.

A second account of the entertainments at Kenilworth had appeared in 1575 prior to Gascoigne s. This was entitled: A Letter: Whearin part of the Entertainment, unto the Queenz Majesty at KILLINGWORTH CASTL in Warwick Sheer, in this Soomerz Progress, 1575, iz sign y Ied: from a freend officer attendant in the Coourt, unto hiz freend a Citizen, and Merchaunt of London (Printed in John Nichols, Progresses of Queen Elizabeth (1823), vol.1, pp.420-484):

…her Highness all along this Tilt-yard rode unto the inner gate next to the base coourt of the Casti: where the Lady of the Lake (famous in King Arthur z book) with two nymphes waiting uppon her, arrayed all in syiks, attending her Highness coming: from the midst of the pooi, whear upon a moovable island, bright blazing with torches, she floting to land, met her Majesty with a well-penned meter and matter after this sort: viz, first of the auncientee of the Casti, whoo had been ownerz of the same e en till this day, most allweyz in the hands of the Earls of Leyceter; hoow shee had kept this Lake sins King Arthur z dayz; and now understanding of her Highness hither cumming, thought it both office and duetie, in humble wize to discover her and her estate; offering up the same her Lake and poour therein, with promise of repayre unto the Coourt. It pleazed her Highness too thank this Lady, and too add withall, we had thought indeed the Lake had been oours, and doo you call it yourz noow? Well, we will herein common more with yoo hereafter.

A Masque of Diana and Iris had been planned for the Kenilworth entertainments but this was cancelled, perhaps because it contains a direct appeal for Elizabeth to get married to Robert Dudley. The text, however, was printed in Gascoigne s, Princely Pleasures at the Courte at Kenelwoorth. (See text above). The two deities discuss the nymph Zabeta, who was Queen Elizabeth herself:

Diana …Zabetae s name, who twentie yeeres or more Did follow me, still skorning Cupid s kinde And vowing so to serve me evermore…

Iris …Wherefore, good Queen, forget Dianaes tysing tale: …How necesserie were for worthy Queenes to wed, That know you wel, whose life alwaies in learning hath beene led. The country craves consent, your virtues vaunt themselfe, And Jove in Heaven would smile to see Diana set on shelfe. …Then geve consent, 0 Queene, to Juno s just desire, Who for your wealth would have you wed, and, for your further hire, Some Empresse wil you make, she bad me tell you thus; Forgive me, Queene; the words are hers; I came not to discusse: I am but messenger; but sure she bade me say, That where you now in princely part have past one pleasant day A world of wealth at wil, you henceforth shall enjoy; In weded state, and therewithall holde up from great annoy; The staffe of your estate; 0 Queen, 0 worthy Queen, Yet never wight felt perfect bus, but such as wedded bene.

The texts suggest Kenilworth is an ancient seat that goes back to medieval times and beyond. In fact it had been given to Dudley by Elizabeth recently.