Elizabethans loved novelty but had a limited vocabulary for discussing and so called everything a deceit, an invention or a device, sometimes a witty device. A device could be anything from an acrostic poem to a meat pie shaped like a fish which they would have loved for its wittiness.

As an example of a device see the 8 page PDF file describing the symbolism in Nicholas Hilliard’s Portrait of Henry Percy, Ninth Earl of Northumberland.

John Davies, Hymnes to Astraea (1599) [R. Krueger (ed.), The Poems of Sir John Davies (Oxford, 1975), pp.77-78]:

TO HER PICTURE

Extreame was his Audacitie

Little his skill, that finisht thee;

I am asham’d and Sorry,

So dull her counterfait should be,

And she so full of glory.

But here are colours red and white,

Each lyne, and each proportion right;

These Lynes, this red, and whitenesse,

Have wanting yet a life and light,

A Majestie, and brightnesse.

Rude counterfaith, I then did erre,

Even now, when I would needes inferre

Great Boldness in my maker:

I did mistake, he was not bold;

Nor durst his eyes her eyes behold:

And this made him mistake her.

This poem glorifies Elizabeth in her final few years. This would be considered a device as it is an acrostic spelling “ELIZABETHA REGINA”. Poems were written in the shape of a diamond, or an egg or even an eagle. Some could be read vertically as well as horizontally.

This love of a witty device is not Elizabethan but goes back to medieval times. In the Elizabethan period it starts to draw upon Renaissance influences and so deeper meanings.

Take as an example an earlier work that has been taken as a seminal work of symbolism.

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, oil on wood

Panofsky’s interpretation was to either take it at face value, two people and a dog, or read a meaning into the images (possibly multiple meanings and layers of meaning). However, we generally have no or little idea about how these images were regarded at the time so there is a danger that art historians are simply creating a job for themselves. This image is one of the most analysed and has created a library of books. The following is taken from the National Gallery website and it keep fairly factual:

“This work is a portrait of Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife, but is not intended as a record of their wedding. His wife is not pregnant, as is often thought, but holding up her full-skirted dress in the contemporary fashion. Arnolfini was a member of a merchant family from Lucca living in Bruges. The couple are shown in a well-appointed interior. The ornate Latin signature translates as ‘Jan van Eyck was here 1434’. The similarity to modern graffiti is not accidental. Van Eyck often inscribed his pictures in a witty way. The mirror reflects two figures in the doorway. One may be the painter himself. Arnolfini raises his right hand as he faces them, perhaps as a greeting. Van Eyck was intensely interested in the effects of light: oil paint allowed him to depict it with great subtlety in this picture, notably on the gleaming brass chandelier.”

In the following painting no one has any idea of what is going on and there is no agreement about any interpretation.

Hans Memling, An Allegory, late 15th century

The following however has a straightforward interpretation.

Lorenzo Lotto, Allegory of Virtue and Vice, 1505

We see the light side and the dark side and the two paths, one of leading to virtue and the other to a life of vice.

When France invaded Northern Italy (Charles VIII, 1494) the Italians were taken by the emblems on their shields and copied the idea but took it much further using their deep understanding of classical allusion. This gave rise to a fashion for emblem books explaining the meaning. This fashion started in Italy but rapidly spread right across Europe and emblem books became best sellers.

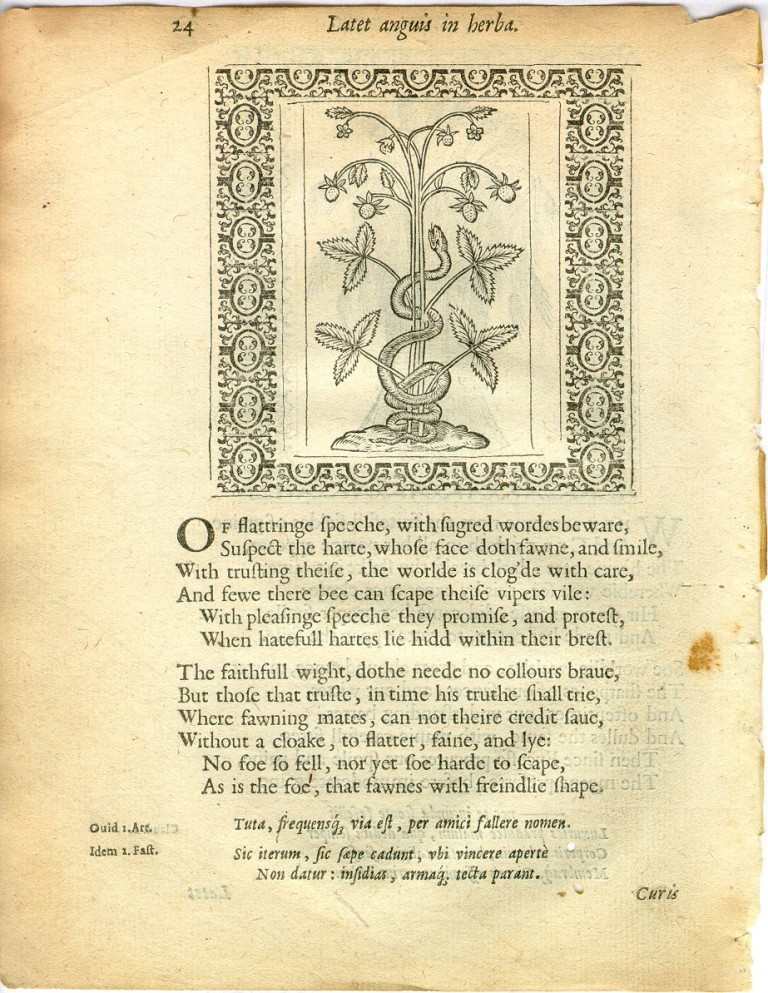

The following is a page from the first emblem book to be translated into English.

A page from Geffrey Whitney: A choice of emblemes, and other devises (the link is a website with the complete scanned book).

Strictly speaking an emblem is an image and a poem (often a sonnet) and you have to take the two together to find the meaning. In the above case it means ‘don’t be taken in by flatterers.’ An emblem applies to everyone. An emblem was often called a device.

An impresa is an image with a short message attached, often in a foreign language. Geoffrey Witney, in A Choice of Emblems (1586), describes an emblem as something:

having some wittie devise expressed with cunning woorkemanship, something obscure to be perceived at the first, wherby, when with further consideration it is understood, it maie the greater delighte the behoulder.

William Camden defines in Remaines (pp. 366-7) an impresa as:

An Impress (as the Italians call it) is a device in Picture with his Motto or Word, borne by Noble and Learned Personages, to notify some particular conceit of their own, as Emblems. . . do propound some general instruction to all. . . . There is required in an Impress . . . a correspondency of the picture, which is as the body; and the Motto, which as the soul giveth it life. That is the body must be of fair representation, and the word in some different language, witty, short and answerable thereunto; neither too obscure, nor too plain, and most commended when it is an Hemistich [a half line of verse], or parcel of a verse.

In other words an impresa relates to a particular person and to understand it we must known something about the person personal circumstances.

Another much discussed painting that includes elements that can be interpreted as symbols is:

Hans Holbein, The Ambassadors, 1533

This painting is another that has given rise to much interpretation. There are obvious symbols such as the anamorphic skull and the lute with a broken string but some of the interpretations are based on a detailed analysis of the dates and times indicated by the astronomical instruments and by geometric shapes that can be drawn over the painting. John North’s The Ambassador’s Secret is one such book containing a detailed interpretation. John North is Emeritus Professor of the History of Philosophy and the Exact Sciences at the University of Groningen, not an art historian, so the interpretation is interesting. Perhaps more interesting is its interpretation as a pair of homosexual lovers based on a detailed analysis and interpretation of all the objects in the picture.

Another painting that also uses images of a skull and a crucifix is:

Joos van Cleve, St Jerome 1524-30

He is pointing at the skull representing death and there is a crucifix behind him.

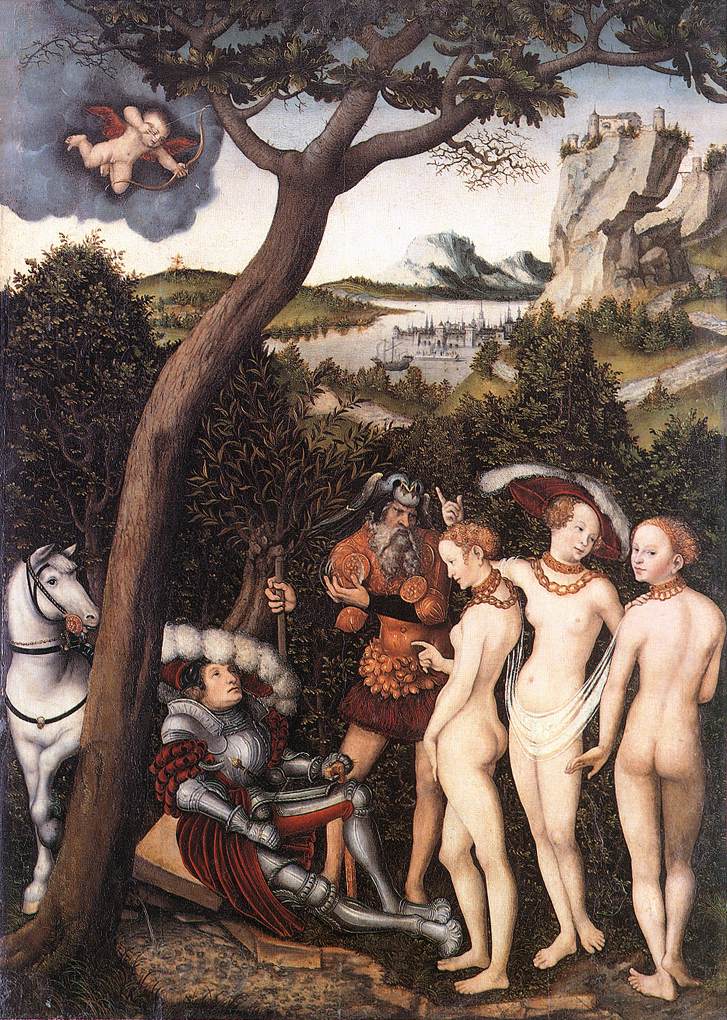

Hans Eworth, Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses, 1569.

The painting is signed ‘HE’ but we don’t know who this refers to. Hans Eworth is a possibility. The frame is the original Tudor frame. One association of this picture is the Judgement of Paris:

Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Judgement of Paris, 1528 (New York, oil on wood). This is one version, Cranach did a number.

Unknown painter, Lord Edward Russell (Woburn Abbey), 1572

This painting has two symbols, a man at the centre of a labyrinth and he is holding a bunch of serpents who are holding the motto ‘The faith of man the fraud of serpents’ on a piece of paper in their mouth. Above his shoulder is the motto ‘Fata Viam Invenient’ or ‘Fate will find a way’. Recently the motto was found in a French emblem book showing a labyrinth (Lyon, 1557) with the same motto above it and it explains it means it is faith in God.

Marcus Gheeraerts, Mary Throckmorton, Lady Scudamore, 1615.

Although difficult to see in this image the motto in the top right reads ‘No spring till now’ and the date 12th March 1615. As we have the exact date we know it refers to the date her son was married. A good example of an impresa as it is specific to her and without knowing the historic event of the marriage it would be impossible to guess although we might speculate it referred to a birth or a marriage.

[Note received from a fan of Lady Scudamore on 30/12/2010: I refer to your painting of Mary Throckmorton [Lady Scudamore] 1615, in my opinion it could refer to the date of her sons marriage [John] to Elizabeth Porter, as she had a turbulent marriage to Sir James Scudamore. The inscription above the portrait of the noble lady probably would refer to that.]

Nicholas Hilliard, Portrait of an Unknown Man Clasping a Hand from a Cloud, 1588

A man is holding a hand of a man or woman that descends from a cloud or group of bubbles or possibly heaven. The motto reads ‘Attici Amoris Ergo’ which defies a clear translation but the words mean ‘Athenian Therefore Love’. Is this a personal in-joke, does it refer to homosexual love, or does it refer to a love of classical knowledge. The meaning is now completely lost so there is little point speculating without additional evidence.

However, some still do and one speculation was based on an analysis of the shapes and number of holes in his lace collar. The number four is significant and this number is associated with Mercury. The god Mercury is the heavenly messenger and so the speculation is that it is an painting of William Shakespeare, also a ‘heavenly’ ‘messenger’. The book containing this speculation was written by the owner of the miniature.

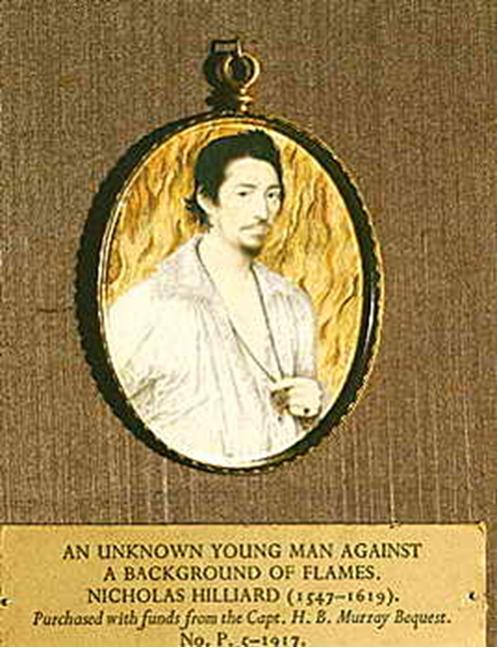

Nicholas Hilliard, Portrait of a young man in flames, c. 1600. A man exhibiting the melancholy of love.

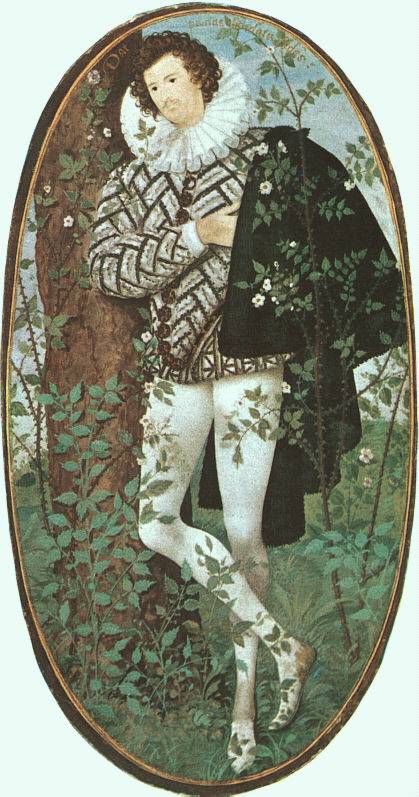

Nicholas Hilliard, Portrait of a young man among roses. This is the first of Hilliard’s cabinet miniatures that he painted between about 1585 and 1595, possibly in response to competition from Isaac Oliver. This young man wears the colours of Elizabeth so it could be related to her.

Isaac Oliver, Unknown Melancholic Man, c1590s (Royal Collection).

William Shakespeare, in Love’s Labour’s Lost (1594, Act ifi: Scene 1) makes fun of melancholic love when Don Armado is advised to:

sigh a note and sing a note. . . with your hat penthouse-like o’er the shop of your eyes, with your arms crossed on your thin-belly doublet, like a rabbit on a spit.

and the young man above has his arms folded like a rabbit on a spit. He is also wearing a ‘penthouse’ at that projects over his face like the upper storey of a shop projects over the street. His is out in the wilds while the couple in inside a cultivated garden.

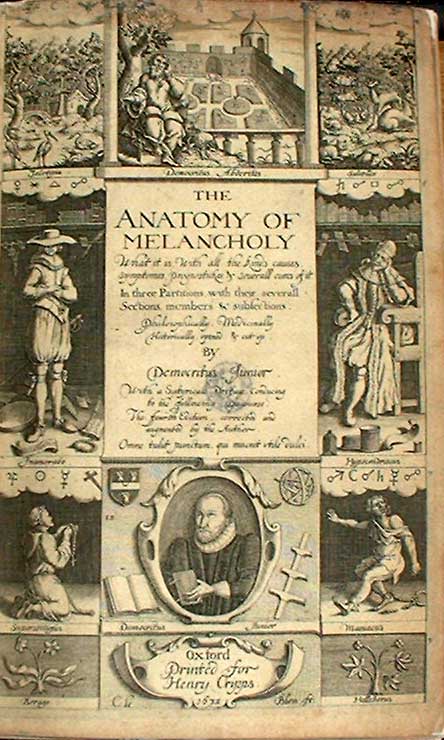

Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy (London, 1628):

What is more pleasant than to walk alone in some solitary grove, betwixt Wood and Water, by a Brook side, to meditate upon some delightsome and pleasant subject… A most incomparable delight it is to melancholize, & build castles in the air… they could spend whole days and nights without sleep, even whole years alone in such contemplations, and phantastical meditations.

Note the melancholia of love in the middle left of the page and the melancholia of thought on the middle right. At the top is man outside a walled garden in the wild wood.

All melancholics were young men, not older men or women. Older men thought it ludicrous and an affectation of rebellious youth. The prime example is Hamlet.

Sir Thomas Tresham was the most notorious Catholic in the country. He was imprisoned in the Tower and while there constructed impresa that were so complex and erudite (involving Greek and Hebrew knowledge) that only a few could understand them and in this way he avoided being accused of being a Catholic.

Memorandum written by Sir Thomas Tresham in 1597 whilst imprisoned at Ely (British Library Add MS 39831, f5V). Describing the symbolic designs he painted in his room:

Most thinges in this contened ar so perpecuus of them selfes that they nede no explaininge, and some ther ar which needeth explanation, for in impresees ys observed to bee so putt downe as differ from vulgar apprehension and yett wyll redely bee interpreted by men of skyll, especially yf skylled in that wherin the imprese or figuratore sene reacheth unto. Thes therfor tending to highest poyncts in divinitye, trynite &c. both forth of scripture and the fathers, also some poyntes forth of historye, musike, geometrye and arithmatik, fordermore using latyn, greeke and hebrewe, in all which to be skylfiill ytt sorteth not with the greatest nomber…

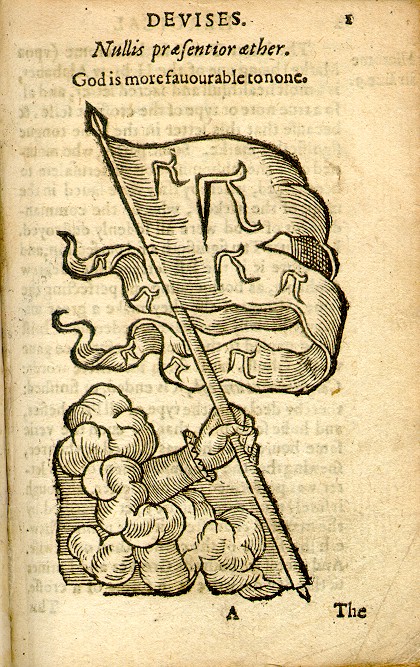

Page from Claude Paradin: The heroicall devises of M. Claudius Paradin, Whereunto are added the Lord Gabriel Symeons and others (the link is to a website with the complete book scanned).