Hilliard, The ‘Heneage Jewel’ also known as the Armada Jewel, V&A, c.1600

On the back is a ship, perhaps representing the ship of state that Elizabeth is steering through the troubled seas. There is a portrait of Elizabeth on the front and inside. The portrait outside is formal and imperial, like a coin. The one inside is softer and personal. Inside the cover over the inner Elizabeth is a red rose and an inscription referring to it as the rose of love. The ship is in the cover over the harder, formal, regal image.

Isaac Oliver, Self-portrait, Royal Collection, c. 1590

A jaunty self-portrait with Oliver’s monogram of a an ‘O’ with an ‘I’ through it.He was born around 1560, the son of a goldsmith like Hilliard. The father was Pierre Olivier which was anglicised to Oliver when he fled from Rouen to England to escape the persecution. His life is very poorly documented unlike Hilliard’s (who was always writing letters and getting into trouble).

He is first recorded aged 17 and then not again until he entered Hilliard’s workshop aged 27. We have no information on this 10 years and it is possible, and suggested by his style of painting that he spent some time in the Netherlands. Haydocke described Oliver as ‘a well profiting scholar’ when he joined Hilliard so it is not likely he was an apprentice. We know Roland Lockey and Hilliard’s son were apprentices but there is no record of Oliver.

Compare the following two miniatures:

Hilliard Young Man, V&A. c. 1585-90

Oliver, Man in Black, V&A, 1590

They are the same shape and both have blue background but Hilliard’s is flatter and Oliver has cast shadow on the background (like Holbein’s Anne of Denmark) and shadow on the face (chiaroscuro).

The calligraphy is interesting, normally Hilliard uses calligraphy and Oliver does not but in this case it is the other way round. Also, Oliver has copied the style of Hilliard’s calligraphy but 1590 Oliver does not use an inscription.

Oliver also shows more of the body than Hilliard and it is very rare for Hilliard to paint more than head and shoulders.

The Hilliard image is brighter and uses a wider range of colours. Oliver’s brushwork follows the contours of the face and he uses a heavy impasto paint but Hilliard uses a thin watercolour paint (in this it is similar to the Holbein/Horenbout comparison). It is possible Oliver joined Hilliard’s workshop to learn miniature painting.

The following quote shows Hilliard’s view of shadow.

Nicholas Hilliard, A Treatise concerning the arte of limning (manuscript, c. 1598-1602/3) printed in R. Thornton & T. Cain (ed.s), A Treatise Concerning the Art of Limning by Nicholas Hilliard (Manchester, 1981):

‘…the principal part of painting or drawing after the life consisteth in the truth of the lyne, … the lyne without shadowe showeth all to a good judgement, but the shadowe without lyne showeth nothing.’

So Hilliard thought that shadow obscured and gets in the way of the truth, almost a moral point. He is thinking in two dimensions and his thinking is medieval.

Edward Norgate, Miniatura or the Art of Limning (1620):

‘Chiar-Oscuro [is] a Species of Limning frequent in Italy but a stranger in England.’

This shows that as late as 1620 shadows were regarded as a foreign invention. Oliver was therefore thought to use foreign techniques.

Oliver, Self-portrait, NPG,c.1590

Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617), portrait of Giovanni Bologna (known as ‘Giambologna’)

This is typical of the Netherlandish art of the period with strong shadows and modelling.

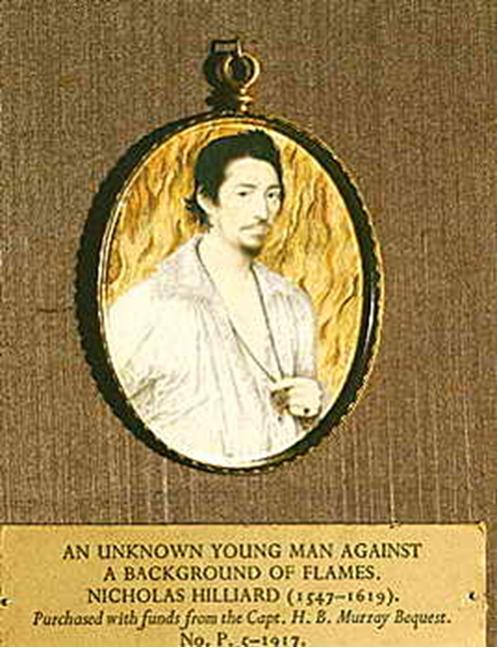

Hilliard/Oliver, Man with background of flames, V&A, c.160

This is difficult to assign to either Hilliard or Oliver and it is still being debated by the experts. It is sometimes ascribed to Hilliard as in the plaque below it but it uses a pointillist stippling technique as was used by Oliver, for example, his portrait of Prince Henry:

Oliver, Prince Henry, Royal Collection, c.1610s

Hilliard, Man clasping a hand, V&A, 1588

However, in this portrait which was by Hilliard the same stippling technique was used for the beard.

Oliver, An Allegorical Scene, Copenhagen, c. 1590-95

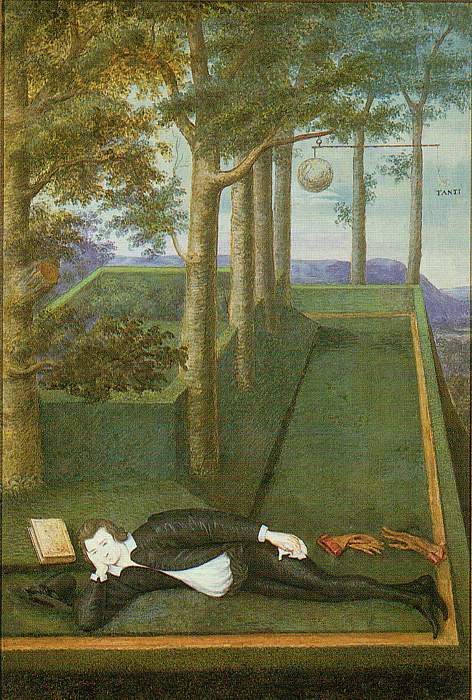

Hilliard, Earl of Northumberland, Rijksmuseum, c.1590-95

This cabinet miniature by Hilliard tries to represent perspective by with strange results. The garden appears to tilt upwards and it abruptly finishes. It looks like a garden on top of a mountain. The inner edge of the right wall becomes the upper edge of the bottom wall. Perhaps the perspective is intentionally incorrect to suggest a mystical symbolic square. Henry Percy, Ninth Earl of Northumberland is shown on the pose of a melancholic, representing deep thought.

Simon Bening, Flight into Egypt, c. 1535-40

Simon Being has wonderful control of perspective all the way through including aerial perspective in the background. This follows the Flemish tradition.

The Elizabethans regarded perspective as a strange foreign invention.

Sir John Harrington, Orlando Furioso (1591), in the preface Sir John drew attention to the use of perspective in his book’s printed illustrations, adding ‘which every one (haply), will not observe’.

‘For the personages of men, the shapes of horses, and such like, are made large at the bottome, and lesser upward, as if you were to behold all the same in a plaine, that which is nearest seemes greatest, and the fardest, shewes smallest, which is the chiefe art in picture.’

It is clear that he does not even have the vocabulary to discuss art and perspective. Such discussions would have been commonplace in the courts of Europe.

Curious Painting

Curious painting was the description most commonly used by Elizabethans to describe the more illusionistic approach to painting (using chiaroscuro, perspective etc.) practised on the Continent.

When Richard Haydocke translated Paolo Lomazzo s Trattato in 1598 (the first book devoted to the theory of painting in English) he published it under the title, A Tracte containinge the Artes of curious Painting, Carveinge & Buildinge (Oxford, 1598). [Note the Warburg Library has a facsimile copy of this book.]

Oliver paints in the curious style and Hilliard does not. There are 50 drawings attributed to Oliver but only 13 are signed and only one dated.

Hilliard, design for the Great Seal of Ireland, British Museum, 1584

This is a late 16th century drawing by Hilliard, compare it with:

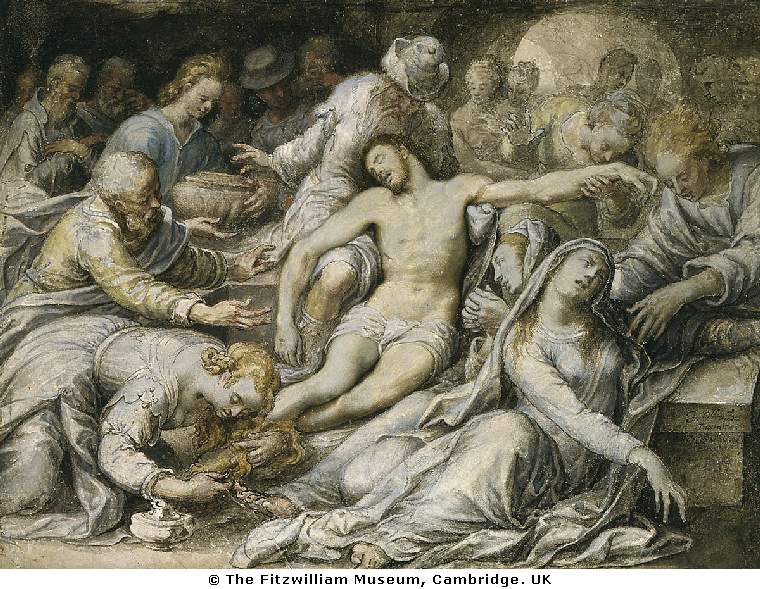

Oliver, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, Cambridge, 1584/86

This late 16th century drawing by Oliver. Late 16th century drawings are very rare.

16th Century Mannerism

Twisted figures, intense emotion, long bodies, small heads, dramatic lighting, a sense of movement, no one is every very sure on their feet, instability and uncertainty, incredibly cramped, pushed to the foreground often with a deep plung into the background. Look at the following examples and Isaac Oliver’s place in them.

School of Fontainebleau, Venus, Louvre, 16th century

Hendrick Goltzius, Venus and Mars

Bartholomaeus Spranger, Venus and Mars

This is Dutch Mannerism of the 1590s, a courtly style that was very fashionable, c. 1595.

Oliver, Nymphs and Satyrs, Royal Collection

The date for this is often given as 1610 but this is pure guesswork. Why did he draw these scenes? Who was the patron?

Oliver became a court painter in James’s reign and his drawings could have been produced for James’s wife Anne of Denmark.

There was an enormous change in England between the late 16th century and the early 17th century.

Michelangelo, Lamentation, British Museum

Oliver, Sir Arundel Talbot, V&A, 1596

We know Oliver went to Italy in 1596 because of the following annotation on the miniature:

Watercolour on vellum,stuck to a playing card,with an inverted heart visible Inscribed on the back by the artist in Latin ‘The 13th day of May 1596 /at Venice /done by Mr Isaac Oliver /Frenchman I.O.May 14th /for ‘8’. A further inscription in a later hand,in Latin,’Living and true image /of Arundel Talbot /Gilded Knight ‘

Oliver, Unknown Lady, V&A, c. 1595-1600

The transparent material is created with just a few brushstrokes. It is larger than you might expect, more of a tondo. It has a flatter face like a Hilliard. A virtuoso display using a very limited palette. Curious painting tended to use a limited palette.

Veronese, Portrait of a Lady, detail

Note the hand in this portrait is similar to that in Oliver’s.

This is entirely stippled and is signed with Oliver’s monogram. Was it produced for a Catholic patron for private worship? Was it hidden in a locket? It could be early 17th century when the king’s wife was Catholic. It is a very unusual pose compared to the other English miniatures of the period.