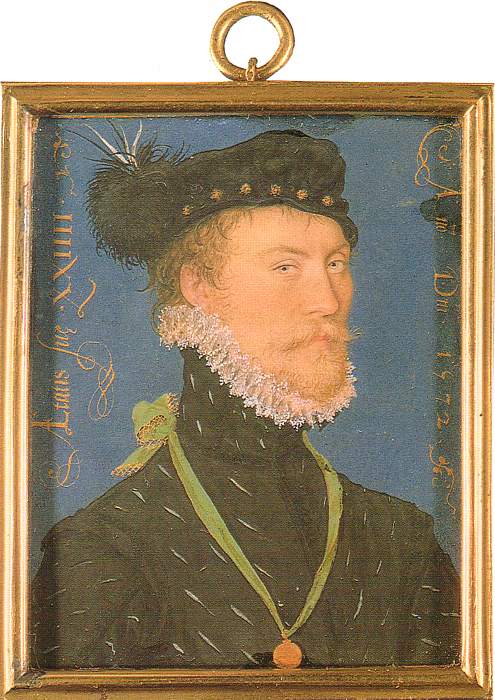

A portrait of Richard Hilliard, father of Nicholas Hilliard, 1577?

His father was a goldsmith and a staunchly Protestant family based in Exeter. He fled the country and went to Geneva when Mary Tudor came to the throne and Nicholas was 10 years old. In common with many rich families of this period Nicholas was sent to the family of a friend to be brought up as this widened his contacts for later life. Nicholas was brought up by the Bodley family and the young boy he was brought up with was Thomas Bodley, founder of the Bodleian Library. So Hilliard was very well educated. He was apprenticed as a goldsmith when he was 15 and was placed with Elizabeth’s goldsmith for 7 years.

He is thought to have become acquainted with portrait miniatures as a goldsmith as they fitted them into lockets. We don’t know if any of the surviving lockets are by Hilliard and we don’t know who taught him limning, he may have been self-taught. Roy Strong believes that limning was a secret art that was past down from one person to another, thus Horenbout taught Holbein, who taught Teerlinc (?), who taught Hilliard (??) but there is no evidence for this.

Hilliard wrote later that Holbein’s method of limning ‘I have ever imitated and hold it the best.’ It is interesting if we compare Holbein’s Mrs Jane Small, 1540, with Hilliard’s Alice Brandon, 1578 (who became his wife).

Holbein, Mrs Pemberton, Jane Small, c. 1540

There are differences that can be seen with a microscope. Holbein’s brushstrokes follow the outlines of the face and Hilliard works with flat strokes. It also seems from careful observation that Holbein worked from the eyes and nose outwards but Hilliard worked from the outline inwards.

The lack of chiaroscuro was described by Hilliard as more honest, as if the person was in full sunshine. It should also be remembered that the portraits were held very close to be viewed.

Hilliard claimed he painted from life but Holbein appears to have scaled full-size drawings down for his miniatures.

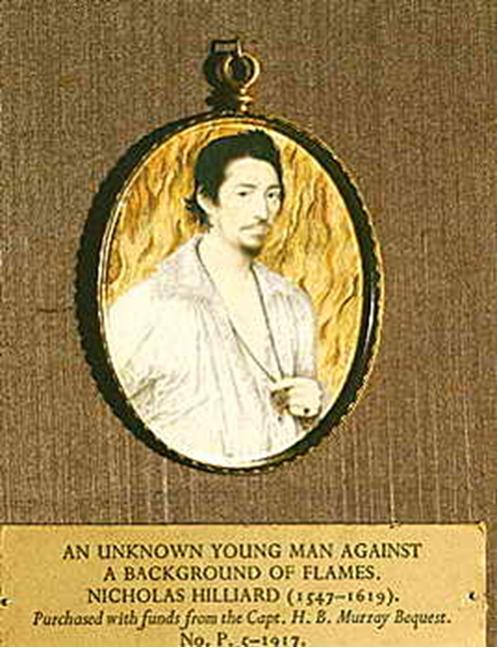

The earliest miniature by Hilliard is this portrait of an unknown man.

He also painted portraits of the Earl of Leicester and this may have led him to Elizabeth. The earliest surviving portrait of Elizabeth by Hilliard is 1572. He never became court painter and this became a complaint of his and so to make money he had to paint anyone who came into his shop in Gutter Lane (of all places), including a fish merchant – from monarch to fish merchant.

The draft patent of 1584 allowed Hilliard the exclusive right to paint the queen’s in miniature but for George Gower to paint her portrait. Who don’t know who drafted the patent but it may have been Gower trying to stop Hilliard from doing full-size portraits. We know Hilliard painted full-size portraits. He painted a ‘fair picture’ (i.e. full-size) of Elizabeth for the Goldsmith’s Company in 1600.

There is a suggestion that the Pelican portrait of Elizabeth is by Hilliard but this is mostly based on us not knowing who else could have painted in that style.

We have an inventory of Elizabeth’s clothes so we know from the detailed description that the clothes Hilliard painted actually existed.

Between 1576 and 1579 Hilliard went to France, maybe to find work at the French court.

Francois Clouet (son of Jean Clouet), Catherine de Medici, c. 1555. Catherine was the mother of the king of France. This is the kind of miniature that Hilliard would have seen in France. When he returned from France he changed from the round to this oval format.

Hilliard, Sir Christopher Hatton, 1580s

Hilliard, Unknown lady, 1580. A very close-up view creating an intimate and romantic feeling.

Hilliard, Elizabeth I, 1595-1600. (Elizabeth was born in 1533, was queen from 1558 when she was 25 and died in 1603 aged 70 after reigning for 45 years).

The lace is produced by dribbling a thick white paint which makes it slightly raised such that it casts a shadow under raking light. Hilliard said he perfected the technique of painting jewels using a secret technique. We now know he first applied gold leaf to the vellum, then clear gum tinted with the colour and picked up with the end of a pin and stuck on the gold leaf.

Why did portrait miniatures become so popular in the 1580s and 1590s? Many survive from this period. Was it a combination of courtly love and the Elizabethan love of secrecy. They were also small and so portable and the painting was relatively inexpensive ( 3-5) and so could be given as a gift by the miserly Elizabeth. She of course expected the recipient to spend 100 on a jewel encrusted locket to keep it in.

Shakespeare and Spenser sonnets address the same courtly love, unrequited love and cruel mistresses as the miniatures. Shakespeare often mentions miniatures in his plays.

Petrarch was the first to address this topic with his writing about his cruel mistress Laura, he says his heart was enflamed with passion (she was already married).

Hilliard, Young Man in Flames.

In one text Sir James Melville describes how Elizabeth took him into her bedroom and unwrapped a portrait miniature of the Earl of Leicester labelled ‘My Lord’. This was when Elizabeth had proposed that Mary Queen of Scots marry the Earl of Leicester, which she was unlikely to do as he was then seen as Elizabeth’s ‘caste off’. So Elizabeth may have been playing a clever political game when she showed Melville her secret miniature.

George Gower, Mary Cornwallis, c. 1575

In this portrait we see the lady has a portrait miniature round her waist in a locket. We do not known whether it was seen at the time as a jewel that happened to contain a portrait or a portrait encrusted with jewels (e.g. Twelfth Night, ‘wear this jewel for me, it contains my portrait.’).

A black male in front of a white female. The black man may be a prince as he wears jewels and a type of toga or it may be that it was simply a clever way to use the alternating black and white layers of the sardonyx (see The Drake Jewel)

The blue oval on black is the lid that folds down with a portrait of Elizabeth inside. There is a portrait of Sir Francis Drake wearing it by Marcus Gheeraerts.

Marcus Gheeraerts, Sir Francis Drake.

The family tradition is that it was given to Drake by Elizabeth.