Holbein the Younger at the Court of Henry VIII

Holbein first visited England in 1526-28 before returning to Basel. He then returned in 1532 and spent the rest of his life based in England until his death, probably from the plague on 1543, aged 45.

His earliest surviving portrait was a commissioned he carried out when he was only 18 of the mayor of Basel, Jakob Meyer and his wife (Basel), 1516. He was not yet a master so we don’t know how he obtained the commission.

Portrait of Dorothea Kannengiesser, 1516 (wife of Jakob Meyer). Note the two portraits are flatter than his later portraits, there is a poor perspective rendition of the arch and Dorothea’s dress lacks any sign of modelling and creases. Unlike his later work Jakob’s black garment is simply black, we cannot tell the material or the texture. In general, male figures were more finely realised and female figures were meant to conform to an ideal and so were generalised.

Hans Burgkmair, Hans Paumgartner (woodcut), 1512

This engraving by Burgkmair shows that Holbein was following the latest German fashion in painting portraits with classical building in the background and a three-quarter view of the person’s head and shoulders.

Hans Holbein the Elder, Unknown Woman (Basel).

Holbein’s father was a leading painter in Augsburg and we believe that Holbein was an apprentice to his father. We can see similarities in the style if we examine his fathers works. The style is ultimately derived from Jan van Eyck.

We have both preparatory drawing for the Meyer’s in silverpoint.

Silverpoint involved applying a wash of ground animal or bird bone to the paper to provide a rough surface. The pen contained a fine metal or silver wire and when it was dragged across the surface it left a very fine trail of metal, It could not be corrected or rubbed out and so it was good for training apprentices as the master could return later and see all the mistakes they had made. Also lines cannot be made heavier by pressing harder they are all of equal thickness so shading can only be done by hatching.

Jacob Meyer in silverpoint (Basel), 1516

Jakob Meyer in chalk (Basel), c.1526

Ten years later he drew Jakob again for the famous altarpiece and we can see how his technique had changed. He has switched to chalk. Chalk was of two types:

Natural – normally black but difficult to use.

Synthetic, made from pigment bound in clay, gum or glue and fashioned into a stick which could be sharpened or made into a blunt stump.

We believe Holbein created his own chalk as no one else in England used it at the time. He made sticks for each of the subtle tones he used, he did not blend colours on the paper.

In 1524-26 Holbein went to France to gain a court appointment but he was not successful as there was no vacancy. There was a tradition of using coloured chalk for portraits in France. Chalk was not unknown to him previously but he abandoned silverpoint altogether at this period.

Jean Clouet, Guillaume Gouffier (Chantilly), c.1516

Clouet was the leading court artist in France and we can see how he blended the beard and had a more linear approach than Holbein. There was a fashion for unfinished portraits in France at the time and the name of the sitter would be folded under and the game was to guess the person. Clouet uses flat shading strokes from top right to bottom left (as he was right-handed). Holbein shows the detail of the hat and he also unusually suggest armour. Holbein’s shading is always top left to bottom right as he was left-handed.

Sir Nicholas Carew (Basel), c. 1527

Holbein came to England in 1526 with a letter of introduction to Sir Thomas More from Erasmus. More was a Privy Councillor at the time, he did not become Lord Chancellor until 1529, but he was still a very powerful figure. More wrote to Erasmus saying there might not be enough work for Holbein but he commissioned a full-size painting of his family which was sadly destroyed by fire in the 18th century. Two full-scale copies survive, one in the NPG, and one small painting at the V&A.

Family of Sir Thomas More (Basel), 1527

This is the drawing Holbein produced which still survives and it shows the names of the sitters and various notes, such as his wife should be sitting on a chair, not kneeling. We assume the drawing was used as a presentation drawing to gain approval from More regarding the layout. The drawing was sent to Erasmus as a gift.

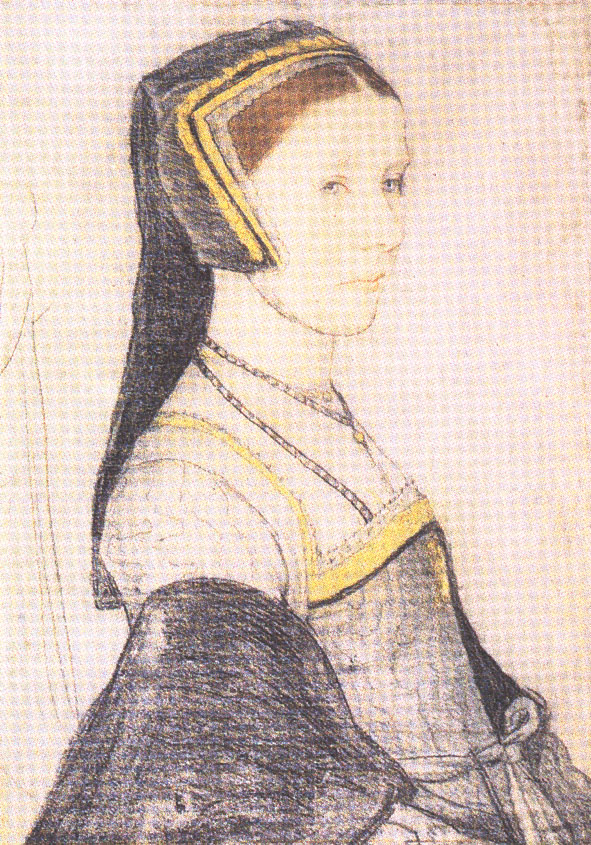

There are about 80 Holbein drawings at Windsor including this study of Anne Cresacre for the More family painting. Anne was to marry More’s son John and she was drawn sitting but was painting standing.

The drawing used for this painting shows Holbein’s use of subtle colouring, compare the beard to the hair, these are different chalks not one shaded darker. In the early 20th century it was described as a watercolour as the chalk work is so fine.

The chalk is not blended or smudged and he has left individual strokes. More is wearing a black satin or silk garment and Holbein is showing a shot silk effect. Again the direction of shading shows he is left-handed.

Cecily Heron (Windsor), More’s third daughter.

We see a change in portraiture style across Europe at this time with a relaxed stance, a three-quarter view (even Holbein’s profiles usually show a glimpse of the hidden eye), caught in a moment of time and suggestive of emotion although unspecified.

Leonardo, Lady with Ermine (Cracow)

This is an earlier example of the new style by Leonardo. This can be compared with the timeless air of late medieval portraits.

Sir Thomas More (New York, Frick Collection), 1527

Holbein also painted More and this can be compared with the Meyer portrait of 1516. The painting of texture is now perfect, Meyer’s clothes could be any material but in More’s portrait we can see each material and recognise it. The effect of velvet is achieved by a complex layering of glazes consisting of jet black and vermilion. He would have seen Italian painting in France and he just missed meeting Leonardo (1452-1519).

The green drapery gives a sense of movement but the vertical and horizontal lines of the cord stabilize the image. More is also more integrated with the background than Meyer. The Meyer background could be a stage-set. More also has integrated illumination and a greater sense of drama. More is in a three-dimensional space achieved by the table edge and the curtain, a device used by Titian and Dürer.

This is a preparatory drawing of More at Windsor Castle. It is pricked for pouncing. Infra-red reflectography reveals an underdrawing of black dots characteristic of pouncing. The drawing was not used to create the painting however. He probably created an auxiliary drawing to prevent the main drawing being destroyed by charcoal dust used when pouncing. An auxiliary drawing is made by placing another sheet of paper under the drawing when pricking it. The black dots of the painting however don’t line up with the holes so there must have been another drawing.

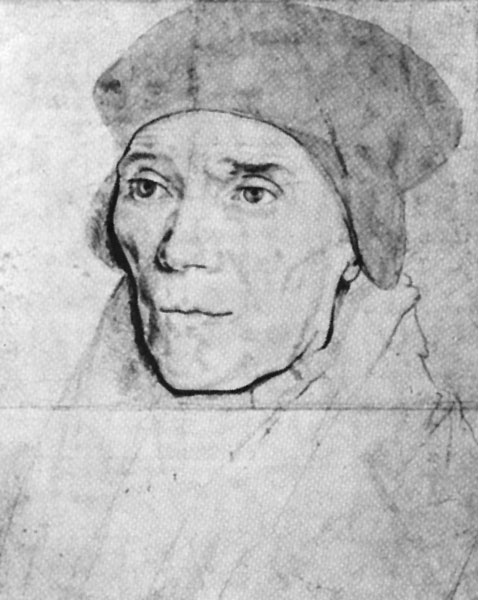

Holbein’s drawing of John Fisher and painting of John Fisher shows it is pricked and cut out. Between the holes there are black dots so it was a pattern created from another pattern.

After Holbein, Bishop John Fisher (NPG)

The Lady Butts drawing and painting match exactly and were copied using the other technique of tracing. This was done by placing the carbon side of a sheet of paper covered in carbon dust against the white canvas of the painting. The drawing was then placed on top and the outline was drawn over using a metalpoint pen. We can see the indentation of the pen on the drawing. Note the number of eye wrinkles has halved between drawing and painting, no doubt based on his patron’s requirements. This copying technique became the main one used by Holbein.

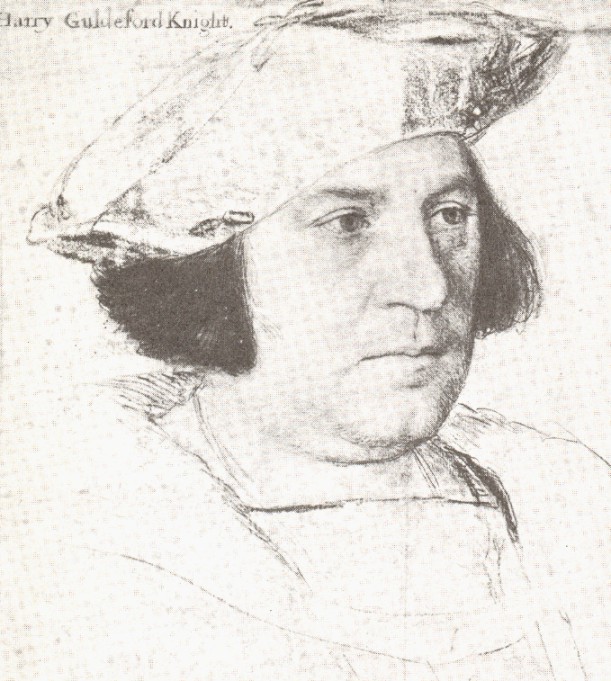

Sir Henry Guildford (Windsor), 1527

The drawing of Guildford shows his face fatter than in the painting.

Sir Henry Guildford (Royal Collection)

His wife’s drawing is different from the painting. She is looking out of the painting but looking sideways in the drawing. In the drawing she has a smile and a coquettish look, the painting is a much sterner, more formal look appropriate to a rich and powerful woman. The convention in Italian paintings was that the woman did not look straight out in order to look virtuous, however, Anne of Denmark and Anne of Cleves look straight out, but they are very powerful women. The drawing of Lady Guildford fits the painting exactly so it was used even though the eyes and mouth were changed.

Lady Mary Guildford (St. Louis, USA), 1527

Lady Mary Guildford (Basel), 1527

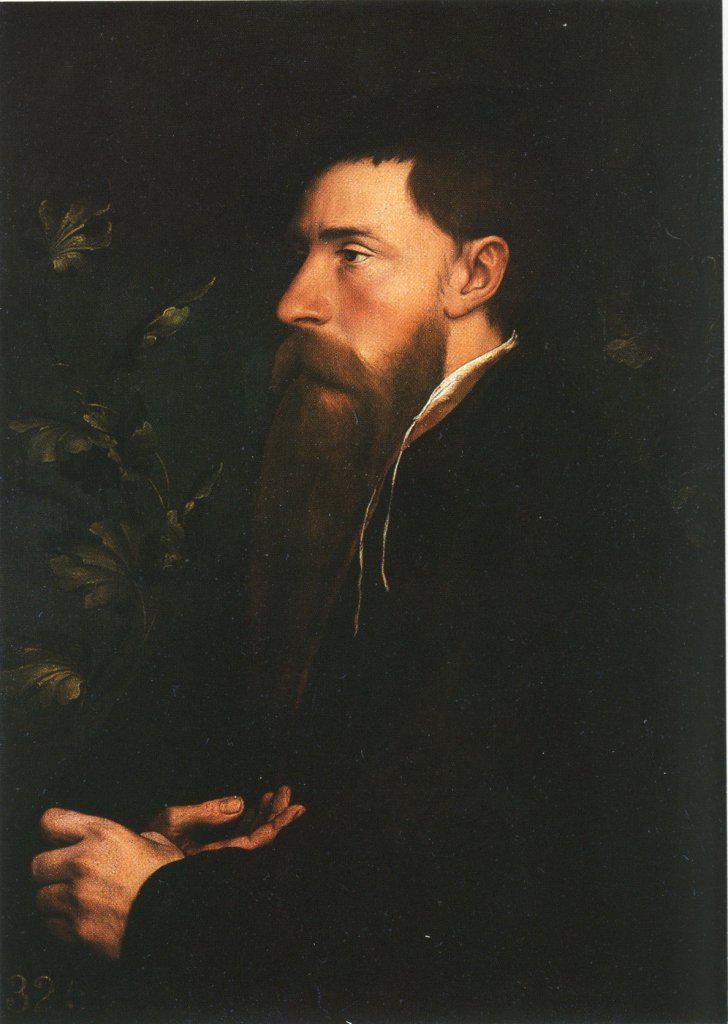

The column is from Vitruvius, branches with leaves crop up in many Holbein pictures but the reason has never been satisfactorily explained. There is a study of a lady in the British Museum with the same costume as Lady Guildford showing it was fashionable.

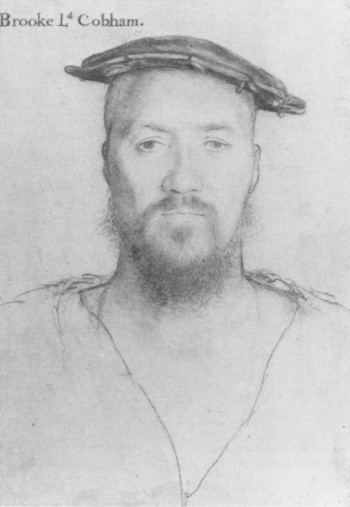

Lord Cobham has an open shirt and we have a copy of Holbein’s portrait when he wears a doublet for reasons of decorum.

Charles Wingfield is wearing a medallion but no shirt at all. We see his hairy chest and nipples even though Holbein would never have painted them.

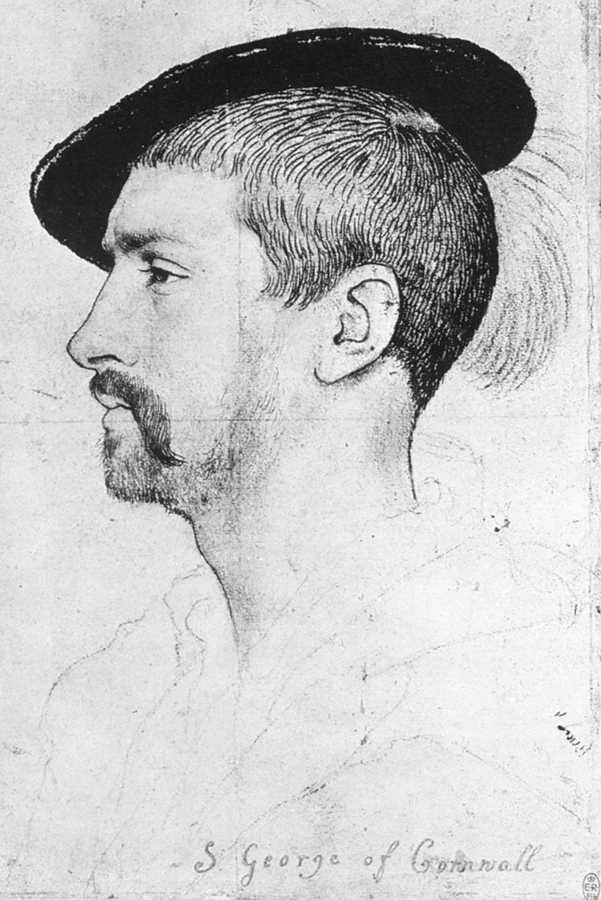

Simon George (Windsor), c. 1535

Compare the Windsor drawing above and the Frankfurt painting below. He has grown a full beard which suddenly became fashionable in 1535 when Henry VIII grew one. Holbein would have invented the beard rather than ask for another sitting.

The painting is not a miniature, Holbein painted other oval paintings. He added the carnation and the hat badge which would have required other drawings, so there are hundreds if not thousands of drawings that have been lost. The clothes would have been lent so that they could be copied exactly while being worn by someone else.

Three Studies of Hands (Louvre)

These are studies of hands for the portrait of Erasmus, see below. A wedding ring on the fourth finger is a later tradition and at this period rings could be worn on any finger or the thumb.

Anne of Cleves (Louvre), c. 1539

Holbein toured Europe over two years painting portraits for Henry VIII of all the eligible princesses in Europe. These included Anne of Cleves and her sister. Stories of ‘the fat mare of Flanders’ are inventions of the eighteenth century, no contemporary documents mention any such thing. Their incompatibility could have been for any reason other than appearance, such as her lack of English, her accent, smell, personality and so on. There was never any criticism of Holbein’s portrait so such stories are a later invention.

Bartel Bruyn the Elder, Anne of Cleves (St. Johns, Oxford), c. 1530s

This is Anne of Cleves by another painter. There is no evidence Holbein had any problem with his portraits misrepresenting anyone.

Sir Richard Southwell (Windsor)

In 1532, when Holbein returned to England his portraits changed. Note in the Southwell drawing the paper is pinkish. This technique provides a mid-tone which could be darkened or lightened using a white chalk or brush. The pink was applied to one side as an overall wash.

John Russell, Earl of Bedford (Windsor)

This chalk only.

Margaret, Lady Elyot (Windsor)

In some portraits at this time he also starts to combine chalk with pen and ink.

Christina of Denmark, Duchess of Milan (NG), 1538

The stories of Christina’s refusal are an eighteenth century invention and no contemporary documents mention them. In fact, she was honoured by the approach but the marriage could not be arranged for political reasons. Henry kept the portrait in his private rooms until he died.