The origins and the conventions of landscape, its iconography, style and especially its techniques. Introducing Crome, Girtin, Towne, Cotman, Morland,Turner and Constable.

- Jacob van Ruisdael, Waterfall near a Village 1656

- Poussin Landscape in the Roman Campagna (Landscape with Travellers Resting), c.1638-9

- Poussin Landscape with a Man killed by a Snake 1648

- Claude Hagar and the Angel 1646

- Claude Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba 1648

- Richard Wilson Lake Avernus and the Island of Capri c.1760

- Richard Wilson Llyn-y-Cau, Caderldris c.1774

- Thomas Gainsborough The Market Cart 1786

- John Crome The Porlingland Oak c.l820

- Crome Yarmouth Harbour – Evening 1817

- Cotman from Liber Studiorum: A Series of Sketches and Studies Millbank on the Thames

- Turner England: Richmond Hill, on the Prince Regent’s Birthday 1819

- Turner Sun Rising Through Vapour, Fishermen Cleaning and Selling Fish 1807

- Turner Dido Building Carthage 1815

- Turner Walton Bridge on Thames, Surrey 1830 from Picturesque Views in England and Wales

- Turner Ulysses deriding Polyphemus – Homer’s Odyssey 1829

- Constable The Opening of Waterloo Bridge 1829

- Constable The Haywain 1824

- And drawings and watercolours in the collections of Tate Britain, Courtauld Institute and British Museum

The Hierarchy of Genres

1.History painting

2.Portrait

3.Genre

4.Landscape

5.Still life

Even though landscape was fourth it was popular in Britain and one third of all the pictures exhibited at the RA were landscapes. There was a re-evaluation of nature during the nineteenth century and we will focus on Romanticism, Realism and Aestheticism. There was a reassessment of landscape across a broad cross section of people and it develops a special place as people move to the cities. A vehicle for fears and fantasies of artists.

J.M. W. Turner’s ‘Ploughing Up Turnips, near Slough’: the cultivation of cultural dissent, The Art Bulletin, Dec, 1995 by Michele L. Miller. Also see Daniels, Landscape, Imagery and National Identity.

Poussin — theatrical, ‘repoussoir’ is the theatrical term for anything that frames a landscape. Diminishing form — figures reducing into the background. Classical robes. Coulisse — flat is also a term for the wings of a stage. Water in the middle ground — gives depth, draws the eye in, and introduces a reliable horizontal surface.

Aerial perspective is the creation of a feeling of depth by changing the colour of the distance. This is typically the use of a bluish or purple hue for distant mountains.

Poussin, Landscape with Travellers Resting

Nicolas Poussin, Landscape with a Man killed by a Snake, probably 1648

Strong light and shade on every object to highlight objects. The eye moves along an S-shaped path. A sure eye that sees great distances. It enables to see further and more clearly than normal. A process of idealisation, an enobling visual experience. We stand above the landscape, monarch of all we survey. A ‘commanding view’.

All Poussin’s greens have gone very dark as he chose the wrong pigment. An Arcadian light, soft and diffuse but strong shadows on objects. A convenient tree shape (that is found in Italy) that echoes the clouds. Echoes are also found in the reflections in the water and the shape of the hills is echoed in other hills giving a sense of harmony. A lyrical or musical sense. It is anchored by the horizontal and vertical lines.

Claude

Landscape with Hagar and the Angel, 1646, Claude, 1604/5? – 1682

The story is told in Genesis 16. The servant girl Hagar became pregnant by Abraham. She quarrelled with Abraham’s wife Sarah, who was childless, and ran away. An angel met her by a spring in the wilderness. He told her that the child, Ishmael, would found a great tribe. Meanwhile she should return to Sarah

(he points the way).

Claude composed this picture on principles of landscape construction developed earlier in the 17th century by Annibale Carracci and Domenichino. This uses a balanced composition, often with trees as a frame at the edge. Buildings are stabilisers (verticals) and distance markers. The foreground often includes figures from a story. The viewpoint is less elevated than that usual in, for example, 16th-century Flemish landscape. The individual items in classical landscape are based on observation, but their selection and ordering within the picture tended to improve on nature.

This work, much admired by Constable, was the favourite of Sir George Beaumont. When he gave his collection to the Gallery he asked to keep this painting until his death.

We see many similarities with the Poussin, trees, water, distance, biblical figures instead of mythological. Many other painters painted this way at the time.

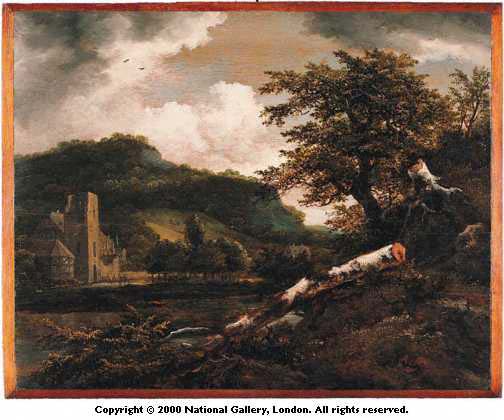

Northern artists — Ruisdael

A Waterfall at the Foot of a Hill, near a Village, probably 1665-70, Jacob van Ruisdael, 1628/9? – 1682

On the hill is the spire of a village church, and other buildings. To the left sheep are being herded over a wooden bridge spanning a ravine. Ruisdael painted a number of imaginary mountainous landscapes with a waterfall rushing towards the lower edge of the picture. This subject was introduced into Dutch painting by Allart van Everdingen, who visited Scandinavia in 1644. On grounds of style the landscape has been dated to the second half of the 1660s, when Ruisdael was living in Amsterdam.

It is more closed in. There is a church giving the only visual anchor, a vertical line. There are echoes between the trees and clouds and the rocks and hills. There is a small cottage with a red roof. Idealising aspects missing but spacial aspects are the same.

English Painting

The reason for a lot of landscapes is the Grand Tour. Artists could make a living painting tourist spots. See Richard Wilson making a tourist spot look like a Poussin.

Richard Wilson,1713-1782, Lake Avernus and the Island of Capricirca 1760

The Grand Tour did not include Greek (because of the war or the difficulty of travel?) so Italy had to stand in for the whole classical world.

People identified areas of Britian as picturesque. See Wilson Llyn-y-Cau,

Richard Wilson, Llyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris (exhibited 1774), Wilson was Welsh and had returned from Rome, also known as Arthur s seat, a site with mythological associations, it wasn t until the mid-19thC that they whole taste for classical landscape had disappeared. It is not of volcanic origin but a cwm (aka corrie or cirque) being one of the classic landforms of glacial erosion.

It is Poussin-like but without trees and has the commanding view. One of the figures has a telescope looking out to Cardigan Bay and the area has mythological associations.

Another artist who adopted the conventions to Britain was Gainsborough.

The Market Cart, 1786. Trees block the view creating a more intimate feel. Note it is portrait format creating a more personal view. There is no escape, it is a contemporary view unlike the others, but timeless and idealised, a new mythology, a non-specific present, like a Flight into Egypt. We don t have strong religious imagery in Britain but religious images survive in the literary tradition. A tricky topic,the religious association would elevate the picture. Note all the vegetables, not all in season at the same time creating a cornucopia. Two painters we will cover in more detail later are:

John Crome, The Poringland Oak (circa 1818-20)

The oak was the pinnacle of tree portraiture for British artists. It was associated with the sturdy character of the British people, and the ships constructed from it defended their liberty. Crome’s picture was exhibited in 1824 as a Study from Nature. It shows a noble tree at Poringland, a village near Norwich. Crome admired the work of Thomas Gainsborough. Here he concentrates Gainsborough’s woodland scenes to a single herotic motif, as if to emphasise a local ancestry for a national symbol. At the same time, the warm cloudy sky is based on the seventeenth-century Dutch painter, Aelbert Cuyp.

Crome founded the Norwich School in his home in 1803. We have an English,

East Anglian even version of Arcadian light, it has a silvery quality.

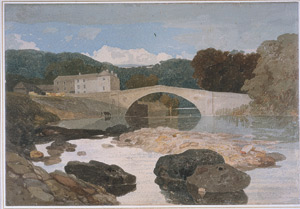

John Sell Cotman, Greta Bridge,

1806-7

Crome Yarmouth Harbour – Evening 1817

Cotman from Turner s (?) Liber Studiorum: A Series of Sketches and Studies Millbank on the Thames

Turner England: Richmond Hill, on the Prince Regent s Birthday 1819

Turner painted this great panorama of the Thames after the Napoleonic War. It shows the view from Richmond Hill, looking west towards Twickenham, and brought Turner’s early series of river scenes to a splendid conclusion. The scene is treated in the grand, classical manner of the seventeenth-century French artist, Claude Lorrain. It presents an Arcadian vision of English scenery, with an explicitly patriotic message in the reference to the birthday of the Prince Regent. The Prince’s official birthday, 23 April, was also St George’s Day (the patron saint of England) and Turner’s own birthday

Turner Sun Rising Through Vapour, Fishermen Cleaning and Selling Fish 1807

Turner Dido Building Carthage 1815

Turner Walton Bridge on Thames, Surrey 1830 from Picturesque Views in England and Wales

Turner Ulysses deriding Polyphemus – Homer s Odyssey 1829

Constable The Opening of Waterloo Bridge 1829

Has been painted within the Claudian conventions. A straight river has been made S-shaped by the use of jutting structures. The bridge replaces the distant hills.

Constable The Haywain 1824

A perfect representation of Claudian features.

There is a direct line from Roman painting to Constable to tourist photographs today. Are there other landscape viewing conventions? E.g. Japanese

Techniques

Canvas, frame, stretcher with keys to tension. Oil paints, linseed oil, which hardens as it dries. Canvas is covered in white with rabbit skin glue. Tight weave or open weave. Priming thin or thick to hide the weave. Open weave was cheap but the artist may also have chosen it for effect.

Brushstrokes, dappled brushwork.

Many of these paintings have been ironed, they stick a new canvas behind when the original canvas gets thin and then iron them together. This removes the spikiness from the surface. There is a Velasquez in the NG of Philip of Spain that has not been ironed and it has a spectacular surface.

Crome Plant Study, graphite.

Crome sketched from nature.

Pencil good at recording shape and light and shade.

Crome Three Pigs is graphite on textured paper as he is interested in the form.

Turner sketch book for Richmond Hill. He is looking for layers in the landscape.

John Crome, Norwich River: Afternoon

Crome Landscape with Cottages. We know Crome used a camera obscura, did he use it for this one?

Watercolour, Turner s sketchbook,

pigment is stuck onto the paper using gum Arabic dissolved in water, whch dries.

Turner used gouche for white rather than leave a reserve.

Cotman, On the Greta, 1805,

watercolour and drawing, good for atmospheric effects.

Turner, The Thames from Richmond Hill, Preparatory Study, 1830-6. May have been done on the spot or in the studio to work out the compositional values.

Turner, Colour Beginning, 1819.

Will be looking at them later.

Crome, Yarmouth Harbour, 1817.

Constable, Yarmouth Jetty, after 1823, not the picture shown which was more a sketch, same title, dated 1818.

Crome, Landscape with Cottages — reworked so was probably a fantasy.

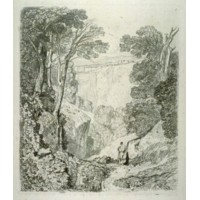

John Sell Cotman, 1782 – 1842. Clifton – from Liber Studiorium, 1838,etchings Etching, Cotman, Liber Restorium.

Turner, Walton Bridge on Thames, Surrey, 1830 (sheep in river). From picturesque Views in England & Wales.

Crome landscape drawing.