There was an extraordinary building boom in the 16th century when more country houses were built than in any other century. In fact many 18th century country houses , such as Chatsworth, were built around an earlier Tudor house. Although the boom started with Henry VIII it continued to grow throughout the century.

The boom was driven by the distribution of church lands after the dissolution and the rapidly expanding ‘middle class’, e.g. lawyers. In fact one historian has said the ‘typical Tudor man was a lawyer on the make.’ It was a century of the nouveau riche and they did not want to be seen in this way so they used building to provide an air of long history – dynasty. The new rich had the money to purchase land which in previous centuries they would have been unable to buy as there was no market in land. The dissolution made so much new land available that an active market in land developed and having bought your land you needed a new house. Modern historians have even found that some new families used coats of arms that were illegally made up.

There was a change in social style as the need for fortified castles disappeared and everyone wanted more comfort and the ability to entertain. This even extended to the monarch, Henry VIII spent 20 years building and rebuilding Hampton Court to make it more luxurious and more comfortable. With Henry VIII’s break with Rome Catholics visiting England were excommunicated so the number of artists visiting dried up. Competition with France became important and Henry VIII competed with François I even to the extend of growing a beard in the French fashion.

Courtiers competed with courtiers and the longest long gallery became a mark of status by the end of the century.

Being able to entertain the king was also a significant use for a house although this was later abused by Elizabeth who bankrupt some families as she moved across southern England.

Compton Wynyates (Warwickshire), completed by c. 1520. Wynyates (‘winyets’) is now in private ownership so can only be visited by special prior arrangement. It is clearly not Italian and has late Gothic elements, there is no symmetry and a piecemeal construction with no grand design, they made it up as they went along. It was built over a long period of time and the tower was added last as a private accommodation for the family. It is brick built although some Italian buildings are brick built depending on the availability of stone.

It has a central courtyard with a great hall opposite the main entrance, typical of buildings from the 14th century. At the dais end of the hall is an oriel window. The entrance to the hall is offset to the left and the door goes into a screens passage with the hall on the right. On the left is the buttery (a small room for wine and beer administered by the butler, the main stock of beer and wine would be in the cellar) and kitchens. At the end of the hall on the left is a door to a processional staircase. The chapel is on the right crossing the inner courtyard and the owner’s rooms surround the chapel.

Note that in architecture ‘oriel’ has two meanings, it refers to either a projecting window above ground level or the large window at the end of a great hall.

Note from the front elevation everything is taller on the right as this is these are the quarters for the owners. Originally it had a courtyard in front, a base court, but such base courts rarely survive as they were made of timber or even canvas, The courtyard would possible have contained stables and servants’ quarters.

Shurland on the Isle of Sheppey, built in 1520s. There is a survey map in the Public Records Office showing it had many courtyards, an inner, a base court with a courtyard attached for stables and a further two courtyards attached to that.

Cotehele (Cornwall), late medieval (pronounced ‘coat-heel’) has an outer court and an inner courtyard with another added. The tower was added in 1620 and built in a medieval style.

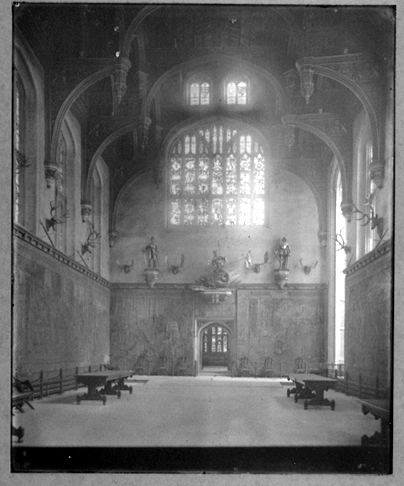

Hampton Court Palace, Great Hall was used for feeding servants (a ‘staff canteen’). The great hall had been losing importance since it started to loose its communal function 300 years previously. It was also a reception hall for important guests and the first room of a processional route:

- Great Hall, a large room where everyone could enter

- Guard Chamber, controlled by the king’s guard (varied from 80 to 300 men), all the doors were kept locked and the guards checked each person’s identification before allowing through to the:

- Presence Chamber, the formal reception room where the king sat under his canopy. Very favoured guests might be invited through to his:

- Privy Chamber, where Henry VIII normally ate his evening meal.

- Private and secret rooms including the bedchamber. Your importance determined how far you got through the sequence of rooms.

Country houses had a scaled down version of this sequence of rooms although there was no guard chamber and the presence chamber could be at the top of the processional staircase.

The great hall was also used for entertainment, and in private houses for conducting business, paying rents and sometimes a quasi-court of law.

Hengrave Hall (Suffolk), 1525-38, Sir Thomas Kytson, is unusual in that it had an internal passage based on the cloisters of the former nunnery. The oriel window on the left of the front was added in Victorian times. The entrance was asymmetrical but the original building was extended to the right to place the door in the middle. The house in unusual in that it has an inner corridor running round the courtyard and the rooms are entered from the corridor. Previously rooms were reached by going through the rooms. The idea of a corridor was taken from the cloisters of medieval monasteries. Note that Wolsey had already build a base court with internal corridor at Hampton Court.

It can be seen that symmetry does not always mean classical and many early castles and churches were symmetrical. When Wolsey built Hampton Court it was symmetrical and Henry added wings at the front.

Hengrave Hall gatehouse (Suffolk), 1525-38. The oriel window is also unusual as it has classical putti at the corbel level. The oriel window is very elaborate with painted sculpture (although the colour is not original they would have been painted). The putti are similar to those on the tomb of Henry VII.

Lacock Abbey (Wiltshire), renovated 1540-53, Sir William Sharrington completely remodelled it. He added another level above the cloisters as an internal passage or corridor with rooms of it.

Titchfield Abbey (Hampshire), addition of c. 1538, Thomas Wriothesley (later Lord Chancellor). He stuck a gigantic Tudor gatehouse on the front, like the original Hampton Court gatehouse. The Hampton Court gatehouse was originally nearly twice as high as it is today and the colour of the brickwork can be seen to change with the rebuilding doen in the 1770s (as it was in danger of collapse).

Ightham Mote (Kent), c.1320-1600, was started in the 1320s and was surrounded by a moat which constrained building.

Hampton Court gatehouse. The roundels on the outer gatehouse were originally not there but in the inner courtyard. The Hampton Court oriel window is 18th century but we have drawings of the original gatehouse. The crenelations served no defensive purpose (by walking over to the wings one could just climb in a window). In the 15th century you needed a license from the monarch to add crenelations as their use suggested ou wished to defend your property. We find that even nuns were applying for their nunneries so it was often clearly purely for decorative purposes. Why did Wolsey crenelate? It gave the impression of a long established building, it made the building look older than it was and so gave the impression of dynasty. It gave the impression of a castle although in reality only a fantasy castle.

Note that the dark walkways we now have would all have been plastered and painted bright white.

There was an increasing interest in Renaissance ornament, not just sculpture but prints, illuminated manuscripts, one or two Italian paintings owned by English patrons, plate, goldsmiths work, jewellery, Venetian glass, artists themselves travelling to England, classical busts, close links to Italian universities, even laymen went to university in Italy, for example, a student might go to Padua University to study law.

We do not think that Italian architectural books came to England until the middle of the 16th century but Jonathan Foyle has found an English bishop had a copy of Alberti in his library much earlier, so there could have been much earlier access and knowledge of Italian Renaissance architectural practice.

Oxburgh Hall (Norfolk). Oxburgh has many points of similarity; tall towered gatehouse, chimneys, crenelations. Both had moats. It is symmetrical from the front, although not from the side.

Herstmonceux Castle (Sussex), from 1441, rebuilt after 1777. Has a moat, symmetry, a gatehouse and crenelations.

Sutton Place (Surrey), c. 1521-33. Richard Weston. There are small naked cherubs above the door which we also find at Wolsey’s Hampton Court. He had been the English ambassador to France where he would have been exposed to these new classical ideas.

Warr Chantry Chapel (Boxgrove Priory, Sussex), c. 1520s, has naked cherubs copied from a French Book of Hours.

Triumph of Bacchus (Royal Collection), c. 1540. This tapestry at Hampton Court was owned by Henry VIII and was woven in Brussels but with the latest grotesque work ultimately from Italy.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Birth of the Virgin (S. Maria Novella, Florence). Grotesque work was discovered in Nero’s Golden House in Rome in 1485 and picked up and promoted by Raphael and spread rapidly.

Carved wooden panels from chapel of Château de Gaillon, early 16th century

Giovanni de Maiano, bust of Roman Caesar (Hampton Court), 1521. The medallions at Hampton Court are by Maiano.

Anon, The Field of the Cloth of Gold (Hampton Court), c. 1540s. The Field of the Cloth of Gold was in 1520 but the painting was not done until the 1540s. We see a Renaissance scallop shell niche and two Renaissance styled fountains. There are classical styled statues on top, a triumphal rounded arch, swags, tiny pilasters with capitals between the windows and either side of the main door. The Tudor rose roundels are like the roundels by Maiano at Hampton Court. It is not classical as there are crenelations, turrets and even fake arrow loops. It is a stage set type building, partly of canvas and timber and partly of brick with real glass windows. To us it looks like a mishmash of styles but to them it could have looked like the latest modern version of the English style with up-to-date French and Italian additions to an English look. We see two architectural ‘languages’, the English and the Italian classical and although both are concerned with representing and demonstrating power they signify this in different ways so the challenge to the English builder was to merge the two languages to form as coherent message.

We must remember that the Elizabethans believed that the White Tower at the Tower of London was built by Julius Caesar and they thought Britain was founded by Brutus from Troy as and the most ancient of British kings was from Greece. The antique was therefore synonymous with the classical.

Anon, Nonsuch Palace (Cambridge), c. 1620

Joris Hoefnagel, Nonsuch Palace (Wallace Collection), 1568

Reconstruction of stucco Roman soldier from Nonsuch

Anon, design for the interior of one of Henry VIII’s palaces (Louvre), c.1540. This could be a design for an interior at Nonsuch Palace.

Gallery of François I (Fontainebleau), c. 1533-40

Ornamental fragments from Hampton Court