Table of Contents

61-01 David Hockney

61-01 David Hockney Podcast (produced by Google NotebookLM)

61-02 Grayson Perry

61-02 Grayson Perry podcast (produced by Google NotebookLM)

61-03 Francis-Bacon

61-03 Francis Bacon Podcast (produced by Google NotebookLM)

61-04 Lucian Freud

YouTube video, see below:

61-05 Antony Gormley

61-05 Antony Gormley podcast produced automatically by Google NotebookLM

YouTube video:

61-06 Damien Hirst

61-06 A podcast on Damien Hirst produced by Google NotebookLM

YouTube video:

61-07 Tracey Emin

61-08 Chris Ofili

YouTube video:

61-09 Sarah Lucas

61-09 Podcast on Sarah Lucas produced by Google NotebookLM

YouTube video:

61-10 Rachel Whiteread

61-10 Notes on Rachel Whiteread

61-10 Podcast on Rachel Whiteread produced by Google NotebookLM (apologies, her name is mispronounced in this podcast, it is ‘reed’ not ‘red’)

YouTube video:

61-11 Banksy

61-11 Podcast on Banksy produced by Google NotebookLM

YouTube video:

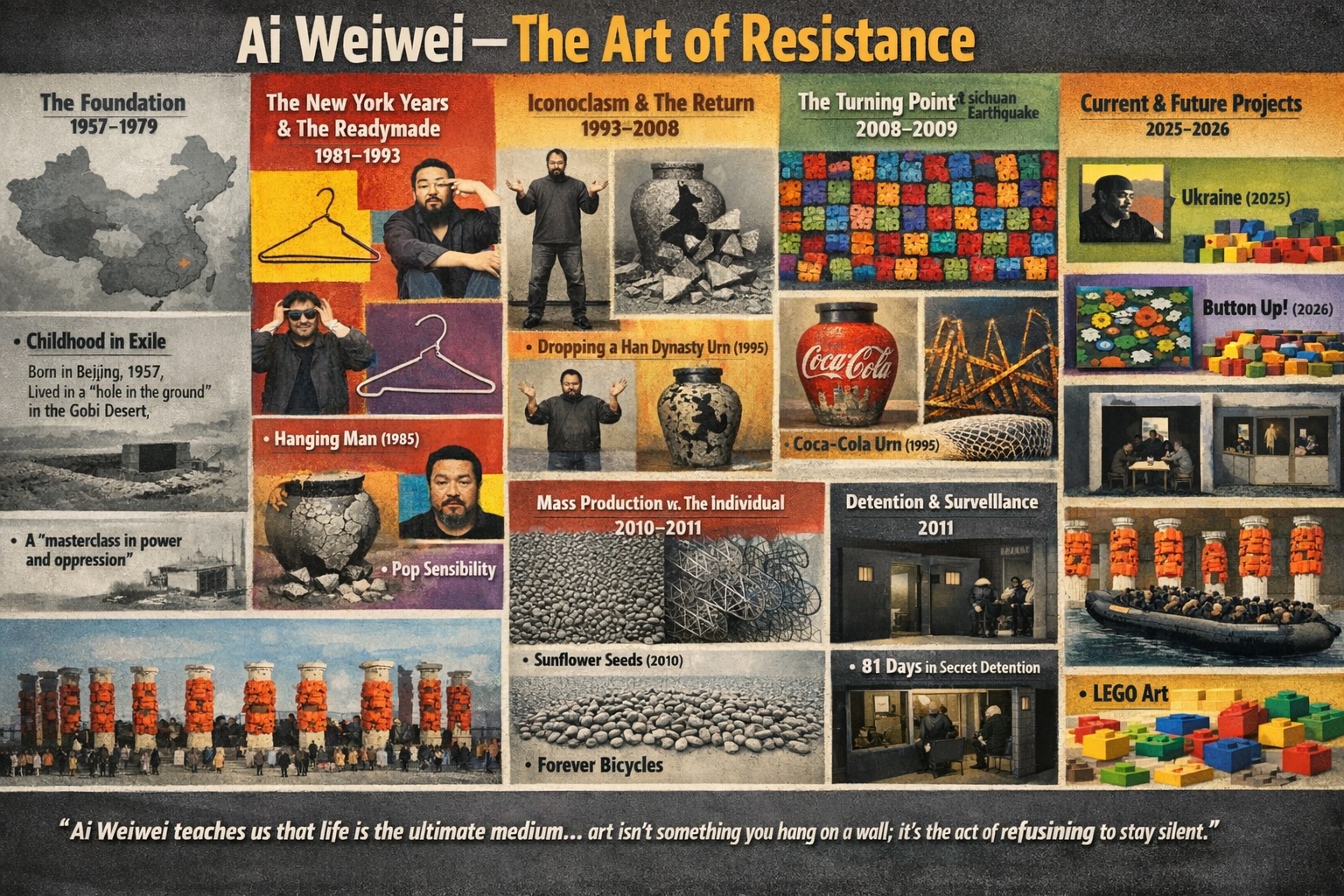

61-12 Ai Weiwei

1. Introduction

Can a single individual truly challenge the monolithic gravity of a superpower? In the case of Ai Weiwei, the answer is found not in a gallery, but in a lifelong performance titled Portrait of the Artist, 1957–Present. Ai is more than a creator of objects; he is a systematic “disrupter” who treats his own biography as his primary medium. To him, art is not a decorative commodity but a fundamental “act of refusing to stay silent.” By distilling personal trauma and political conviction into provocative narratives, Ai has created a roadmap for how the creative spirit can confront absolute authority, proving that when the state attempts to erase the individual, the individual must become the art.

2. Destruction as a Masterclass in Resilience

Ai Weiwei’s understanding of power began with its brutal application. Born in 1957 to the poet laureate Ai Qing, his life opened with a “crash course in political repression.” When his father was branded an enemy of the people, the family was purged to the edge of the Gobi Desert. In this “internal exile,” one of China’s greatest literary minds was reduced to cleaning communal toilets, a visceral humiliation that Ai witnessed daily.

However, this period was also a masterclass in survival. Amidst the harsh landscape, young Ai learned to make bricks and build furniture—practical skills that would later inform his monumental installations. This “imprisonment without arrest” transformed his later work into something deeper than aesthetics; it became a testament to the resilience required to endure when the world is built on the manual labor of the oppressed.

3. The Power of the “Readymade” Middle Finger

During his years in New York City’s East Village (1983–1993), Ai’s artistic vocabulary expanded through the lens of Western avant-garde. He became obsessed with Marcel Duchamp’s “readymades,” even bending a wire coat hanger into a profile of the artist. To survive, he utilized a “gambler’s instinct” as a professional blackjack player in Atlantic City, a trait that would later define his high-stakes political maneuvers.

This period birthed the Study of Perspective series. While appearing as crude tourist snapshots, the series is a sophisticated parody of Renaissance perspective studies. By extending his middle finger toward icons of power—from Tiananmen Square to the White House—Ai makes his gesture the focal point, rendering the massive monuments and the institutions they represent secondary and submissive.

The obscene gesture is today interpreted as meaning “f-off” but it goes back to ancient Greece when the phallic symbol was used to mock someone by indicating they were submissive.

4. Why Breaking a 2,000-Year-Old Urn Was an Act of Remembrance

In 1995, Ai produced his most iconoclastic work: Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn. Captured in three clinical photographs, Ai shatters a ceremonial antiquity. This was not a spontaneous act of vandalism but a calculated performance first published in The White Book, one of his influential underground art publications. In fact, Ai broke two urns to capture the perfect shot, highlighting the intentionality of the gesture.

By destroying the urn, he commented on the “Four Olds” (old customs, habits, culture, and ideas) targeted for elimination during the Cultural Revolution. The world’s outrage over a single broken pot contrasted sharply with the state-led obliteration of thousands of temples and historical sites Ai saw during his childhood. He was forcing a world with a short memory to recognize the state’s legacy of cultural erasure.

Ai countered criticism by invoking Chairman Mao, who told people they could only build a new world by destroying the old one.

5. Turning “Made in China” into a Human Face

In 2010, Ai filled the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern with Sunflower Seeds, an installation of 100 million handcrafted porcelain seeds. The scale was staggering: 1,600 artisans in Jingdezhen, the ancient “porcelain capital,” worked for over two years. Each seed was hand-sculpted and hand-painted before being fired at 1,300 degrees Celsius.

The work subverts the concept of “cheap mass production.” While the seeds look identical from the bridge above, close inspection reveals each is unique. The installation was eventually roped off because the friction of visitors walking on the seeds created a hazardous ceramic dust, a metaphor for the physical toll of mass labor. For Ai, the seeds evoked both the propaganda of the Mao era—where the people were sunflowers turning toward the “sun”—and his personal memory of sharing seeds as treats during his childhood poverty in Xinjiang.

6. The Citizen Investigation: Collecting Names the State Erased

Following the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, Ai moved from conceptual play to urgent activism. Outraged by the “shoddy construction” that caused schools to collapse while other buildings stood, he launched a “citizen investigation” to collect the names of the over 5,000 children the government refused to acknowledge.

This manifested in Remembering, 9,000 backpacks on the façade of the Haus der Kunst, and Straight, a somber landscape made from 150 tonnes of salvaged steel rebar. Ai’s team spent four years manually straightening each mangled bar. When viewed from above, the undulating stacks of steel resemble a seismograph reading, a literal recording of the trauma the state tried to straighten and hide.

Among the backpacks, a quote from a bereaved mother was spelled out in Chinese characters: “She lived happily for seven years in this world.”

7. Flipping the Lens on Surveillance

Ai’s activism led to his 81-day secret detention in 2011. He responded with S.A.C.R.E.D., six iron boxes containing hyper-realistic dioramas of his cell. The acronym stands for: Supper, Accusers, Cleansing, Ritual, Entropy, and Doubt. These dioramas depict Ai eating and using the toilet while two guards stand inches away, watching his every move.

When the work premiered in 2013 at the Chiesa di Sant’Antonin in Venice, the church setting deliberately evoked the “Stations of the Cross.” By forcing viewers to peer through small apertures to see the guards watching the artist, Ai “upturns the surveillance situation,” transforming the audience into complicit voyeurs and exposing the claustrophobic reality of state control.

8. The Political Power of a Toy: The LEGO Controversy

Even while under house arrest with his passport confiscated, Ai maintained a global presence. For his 2014 exhibition at Alcatraz, he created the Trace series—portraits of 176 prisoners of conscience made entirely from LEGO bricks. When LEGO initially refused to sell him bricks in bulk for “political” work, Ai turned the restriction into a global dialogue.

Supporters worldwide donated bricks, demonstrating that a “toy” could become a formidable political tool. This incident underscored his philosophy that art is found in the struggle for expression, not the materials themselves. His LEGO self-portraits, which later sold for millions, remain a testament to his ability to use the “mass-produced” to celebrate the individual.

9. From National Icon to Global Refugee Advocate

Ai Weiwei’s trajectory moved from the center of the Chinese establishment—as a consultant on the “Bird’s Nest” stadium for the 2008 Olympics—to a global humanitarian voice. After denouncing the Olympics as propaganda, he focused on the global refugee crisis, producing the feature-length documentary Human Flow (2017).

His recent work, like Safe Passage (14,000 life jackets on the Konzerthaus Berlin) and Law of the Journey (a 60-meter rubber boat), brings the “human flow” into the heart of Europe. Notably, the massive rubber boat in Law of the Journey was manufactured in a Chinese factory that produces the actual, precarious vessels used by refugees—a haunting meta-commentary on the global reach of “Made in China.”

10. Conclusion: Life as the Ultimate Medium

Ai Weiwei’s legacy is not a collection of objects to be curated, but a precedent for the artist as a citizen. For Ai, art is a way of living—a continuous self-portrait that bridges the gap between the internal exile of his youth and the global crises of the present. He reminds us that in an era of mass surveillance and institutional power, the individual has a non-negotiable responsibility to speak.

As we look at the scale of his work, from a single porcelain seed to 150 tonnes of straightened steel, we must ask ourselves: In a world designed to manipulate mass consciousness, what is our individual responsibility to break the silence?

61-13 Paulo Rego (to be recorded)

61-14 Joseph Beuys (to be recorded)

61-15 Anselm Kiefer (to be recorded)

61-16 Gerhard Richter (to be recorded)

61-17 Anish Kapoor (to be recorded)

61-18 Jeff Koons

61-18 Jeff Koons lecture notes

61-18 Jeff Koons Briefing

This talk is a summary of Jeff Koons’ life, career, artistic themes, and key works, based on excerpts from a lecture series about Western art. Koons is presented as a controversial but highly influential contemporary artist who challenges traditional notions of art by blurring the lines between high art and popular culture, often through the use of consumerism, kitsch, and art historical references.

Key Themes and Ideas:

- Early Life and Education: Jeff Koons was born in 1955 in York, Pennsylvania. His father, an interior designer, encouraged his early artistic talent. He studied at the Maryland Institute College of Art and briefly at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He met Salvador Dalí in New York.

- “Jeff Koons, born January 21, 1955, in York, Pennsylvania, is an American artist renowned for his bold, often controversial works that blur the lines between high art and popular culture.”

- Rise to Prominence: Koons gained prominence in the mid-1980s with series like “Pre-New” and “The New,” exploring consumerism and kitsch. He worked as a commodities broker on Wall Street in the early 1980s to fund his art.

- “The mid-1980s marked Koons’ rise to prominence in the art world. He began exploring themes of consumerism, kitsch, and popular culture in his work.”

- Provocative Works and Controversy: The late 1980s and early 1990s saw Koons pushing boundaries with series like “Banality” and “Made in Heaven,” the latter featuring explicit images of Koons with Ilona Staller, sparking considerable controversy. He also created “Michael Jackson and Bubbles” during this time.

- “The late 1980s and early 1990s saw Koons pushing boundaries with provocative series like ‘Banality’ and ‘Made in Heaven’.”

- Large-Scale Production and Commercial Success: Koons employs a factory-like studio with numerous assistants, similar to Andy Warhol’s approach. His “Celebration” series, including the “Balloon Dog” sculptures, became synonymous with his work. In the 2010s, he achieved unprecedented commercial success, with his “Balloon Dog (Orange)” and “Rabbit” breaking auction records.

- “Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Koons continued to produce large-scale works, often employing a factory-like studio with numerous assistants, reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s approach.”

- “‘Balloon Dog (Orange)’ sold for $58.4 million in 2013, setting a record for a work by a living artist. This record was broken again in 2019 when another version of ‘Rabbit’ sold for $91.1 million.”

- Artistic Themes and Philosophy: Koons’ work often challenges perceptions of art, commerce, and popular culture. He explores consumerism, childhood nostalgia, and the blurring of lines between high and low art. He aims to create art that is accessible and empowering to viewers.

- “His work, which spans painting, sculpture, and installation, continues to challenge perceptions of art, commerce, and popular culture, cementing his place as one of the most influential and controversial artists of our time.”

- “My work is a support system for people to feel good about themselves.”

- “The job of the artist is to make a gesture and really show people what their potential is. It’s not about the object, and it’s not about the image; it’s about the viewer. That’s where the art happens.”

- “I try to create work that doesn’t make viewers feel they’re being spoken down to, so they feel open participation.”

- “Art to me is a humanitarian act and I believe that there is a responsibility that art should somehow be able to effect mankind, to make the word a better place.”

- Koons’ Artistic Processes: Koons utilises techniques to explore and blur the lines between high art and low culture, often recreating existing art from his own childhood but on a mass scale, such as recreating Old Master paintings to sell at his father’s furniture store. He is know to blend minimalist styles with playfulness.

- “When he was young Koons would often recreating Old Master paintings to sell at his father’s furniture store.”

- “The sculpture combines a minimalist style with a sense of play.”

- Major Works and Series: The document references numerous series and specific works, including:

- “Early Works” (1977): Explores many elements present in his later works.

- “Inflatables” (1979): Explores kitsch and consumer culture, questioning the meaning or intention of art.

- “The New” (1980): Vacuum cleaners in plexiglass boxes, elevating everyday objects. “It’s a commercial world, and morality is based generally around economics, and that’s taking place in the art gallery.”

- “Equilibrium” (1985): Basketballs suspended in water, intersecting art and science, representing transience.

- “Luxury and Degradation” (1986): Reproductions of advertisements, critiquing status symbols.

- “Statuary” (1986): “Rabbit,” a stainless steel sculpture, becomes iconic.

- “Banality” (1988): “Michael Jackson and Bubbles,” porcelain sculpture of pop star and chimpanzee.

- “Made in Heaven” (1989-91): Explicit sexual poses with Ilona Staller, challenging boundaries.

- “Puppy” (1992): Topiary sculpture symbolizing confidence and love.

- “Celebration” (1994): “Balloon Dog” and “Hanging Heart,” exploring love, celebration, and luxury. “A very optimistic piece, it’s a balloon that a clown would maybe twist for you at a birthday party.”

- “EasyFun” (1999): Exploring childhood nostalgia and consumer culture.

- “Split-Rocker” (2000): Monumental floral sculpture combining children’s rocking toys.

- “EasyFun-Ethereal” (2000s): Complex collage-like paintings.

- “Popeye” (2002): Blending pop culture, consumerism, and art historical references.

- “Hybrids” (2004-2011): Continued exploration of childhood, luxury, and popular culture.

- “Hulk Elvis” (2007): Combines images of the Hulk with American iconography. “My work is a support system for people to feel good about themselves.”

- “Antiquity” (2008): “Balloon Venus,” combining ancient iconography with balloon-like forms.

- “Gazing Ball” (2013): Recreations of famous artworks with a blue mirrored ball. “This experience is about you, your desires, your interests, your participation, your relationship with this image.”

- “Moon Phases” (2023): Sculptures on the Moon, celebrating human creativity.

- Criticism and Controversy: Despite his success, Koons remains a polarizing figure, with critics divided on the merits of his work. He has faced copyright infringement lawsuits.

- Current Status: Koons continues to create and exhibit globally, maintaining studios in New York City and York, Pennsylvania.

Overall Impression:

The source portrays Jeff Koons as a highly successful and influential, yet controversial, artist. He is presented as a master of self-promotion and a keen observer of contemporary culture, whose work challenges viewers to question traditional notions of art and value. His art can be seen as a reflection of consumerism and celebrity culture, pushing the boundaries of what is considered art.