15-01 British Academic Painting

My notes on British Academic painting

A chat created by Google NotebookLM based on my notes on Academic Painting

Cannibals, Scandals, and Chaos: 6 Surprising Truths About the Birth of the British Art World

We often think of artists as natural rule-breakers, rebels pushing against the establishment. But for a long time, the British art world was the opposite: a place of rigid rules and strict control, dominated by a single, all-powerful institution. This was the era of the Royal Academy. Founded in 1768, it was the ultimate gatekeeper, wielding unparalleled influence over an artist’s career and establishing a virtual monopoly on taste that would not be seriously challenged for a century.

Behind the formal facade of this prestigious institution, however, lies a history filled with shocking scandals, chaotic events, and counter-intuitive truths. It was a world built on surprising foundations and challenged by defiant individuals. Here are six of the most shocking facts about this pivotal era in art history.

1. The World’s Most Prestigious Art Club Was Funded by Ticket Sales

Compared to its European rivals, Britain was a latecomer to the game of establishing a national art academy. The principal reason for this delay was money. While countries like France saw art as a vital state-sponsored propaganda tool, the British government never regarded it as important.

The Royal Academy of Arts was only founded in 1768 because it came with a unique financial model: it was entirely self-financing. King George III agreed to its creation on the condition that it cost him nothing. All of the Academy’s costs, from teaching to facilities, were covered by the admission charge to its annual public exhibition. This simple fact reveals a profound truth about the British establishment’s view of art—it was a private enterprise, not a national priority.

2. A Female Artist’s Self-Portrait Was a Radical Act of Defiance

In 1616, Artemisia Gentileschi became the first woman ever admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence. Her life was marked by a brutal assault by another artist and a grueling public trial where she, the victim, was tortured to ‘verify’ her testimony. This context makes her powerful self-portraits not just professionally radical, but acts of profound personal survival and assertion. Her work continually challenged the conventions of her time, and none more so than her Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting.

The portrait’s most revolutionary act was in its depiction of the artist herself. Gentileschi painted herself not as a refined lady who dabbled in the arts, but as a working professional, physically engaged in her craft, sleeves rolled up and getting dirty. This was a radical departure from the norm. Artists of the era went to great lengths to emphasize the intellectual nature of their work over its physical demands.

Artists during and after the Renaissance were always keen to disassociate themselves from manual work. It was concerned with status, artists wanted to emphasize the intellectual aspect of painting… rather than the manual work of putting paint on canvas. This is a profound message from Gentileschi.

Her self-portrait was a powerful statement on status, intellectualism, and the reality of being a working female artist in a world designed by and for men.

3. All Art Was Judged by a Strict Six-Level Hierarchy

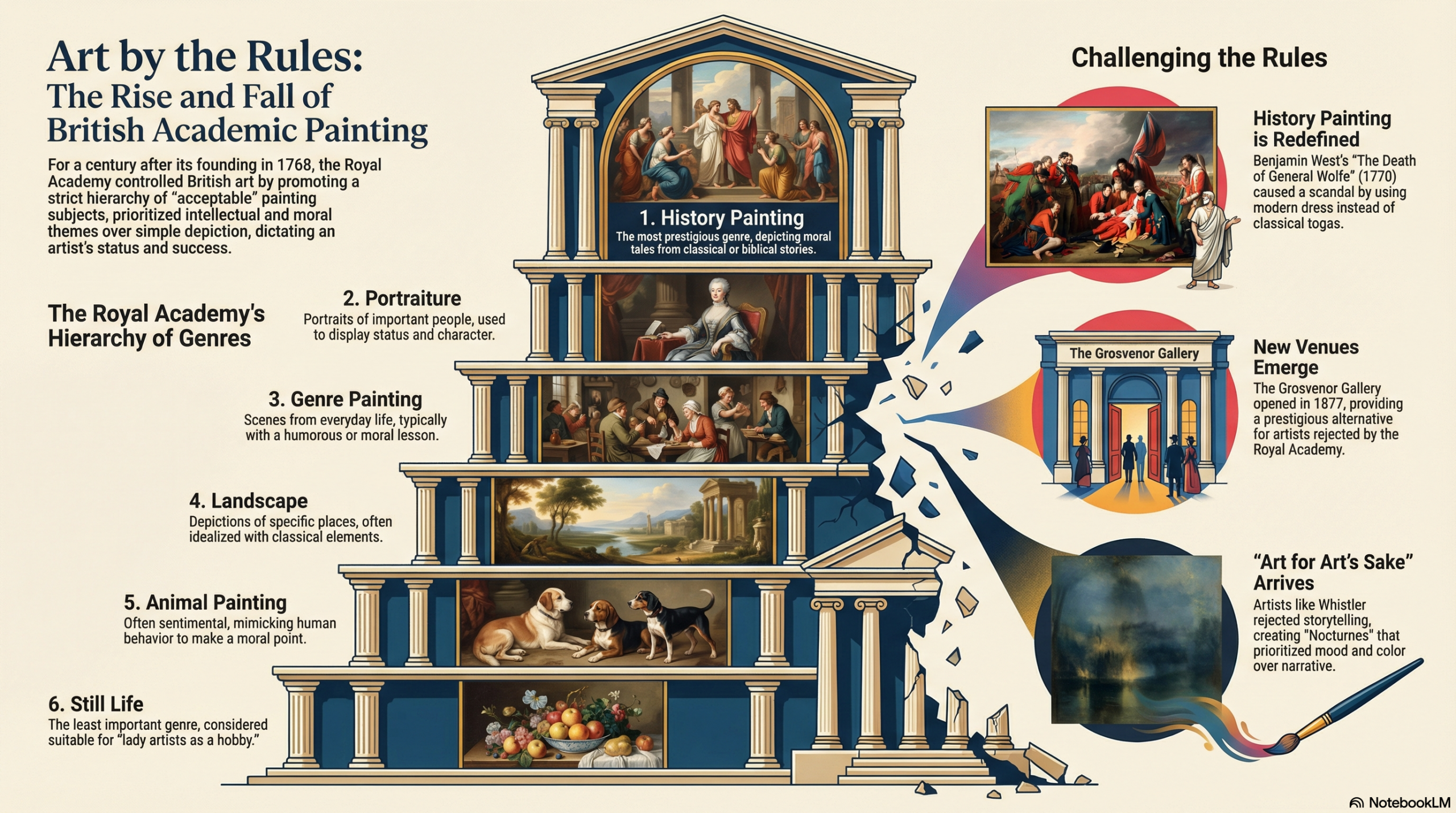

The Royal Academy, under its first president Sir Joshua Reynolds, imposed a rigid hierarchy of genres that defined the importance and moral worth of every painting. The grand purpose of art was seen as intellectual expression, not the “mechanical copying of particular appearance.” This belief was codified into six distinct categories, ranked from most to least important:

1. History painting: A classical or Bible story with a moral point.

2. Portraits: Depictions of a particular person.

3. Genre or subject painting: Humorous scenes, often with a moral.

4. Landscapes: Paintings of particular places.

5. Animal painting: Often mimicking human behavior.

6. Still Life: Considered the least important, suitable for “lady artists as a hobby.”

This hierarchy wasn’t merely an academic exercise; it directly influenced a painting’s price, an artist’s commissions, and their very standing in the social and professional order.

4. A Painting in Modern Clothes Caused a Royal Scandal

In 1770, the American artist Benjamin West decided to push the boundaries of the Academy’s strict hierarchy. His painting, The Death of General Wolfe, depicted a major contemporary historical event—the highest genre of “history painting.” But it ignited a fierce debate that reached the King himself.

The controversy stemmed from West’s decision to paint the figures in their contemporary military uniforms instead of the accepted classical togas. Powerful figures, including the Academy’s own president, Sir Joshua Reynolds, strongly urged West to paint the figures in classical togas, believing modern dress detracted from the event’s timeless heroism. This was seen as a major breach of decorum that compromised the event’s dignity, and the painting was so controversial that King George III refused to purchase it. West defended his artistic choice by stating:

‘the same truth that guides the pen of the historian should govern the pencil [paintbrush] of the artist.’

Despite the initial uproar, the painting eventually overcame all objections. Its success helped inaugurate a move toward greater historical accuracy in painting, forever changing the rules of the genre.

5. Art Exhibitions Were Overcrowded, Chaotic Social Events

Forget the quiet, contemplative galleries we know today. The Royal Academy’s annual Summer Exhibition was a major, chaotic social event—a place “to be seen” as much as to see art. The shows were so popular that, as observer Horace Walpole noted, “The rage to see these exhibitions is so great, that sometimes one cannot pass through the streets were they are”.

Inside, paintings were crammed “frame-to-frame, floor to ceiling.” An artist’s success depended on securing a good spot, ideally “on the line” (at eye level). The crowds were so thick that John Constable began painting his famous “six-footers” simply so they would be large enough to be seen above the throng. The scene was satirized by caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson, who depicted visitors tumbling down the impractical, steep staircase at Somerset House—a perfect metaphor for the chaos and for attendees who were often more interested in other visitors than in the art on the walls.

6. A Founding Member of the Royal Academy Was a Cannibal

Perhaps the most bizarre fact in the Royal Academy’s history concerns Johan Zoffany, a respected German court painter, a key founder of the Academy, and a man buried near his contemporary Thomas Gainsborough. His official biography includes a shocking and macabre detail that stands in stark contrast to his esteemed position.

He is best known as ‘the first and last Royal Academician to have become a cannibal’.

The context for this gruesome distinction is as tragic as it is strange. While returning from India, Zoffany was shipwrecked on the Andaman Islands. As the survivors began to starve, they drew lots to decide who would be sacrificed. A young sailor drew the short straw and was duly eaten. It remains one of the most unsettling and unexpected pieces of trivia in the annals of art history.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of a Blank Canvas

The story of the British art world’s birth shows that even at its most formal and rule-bound, the world of art has always been filled with human drama, rebellion, and unexpected chaos. The absolute power of the Royal Academy eventually began to fade with the rise of alternative venues like the Grosvenor Gallery, which provided a home for the avant-garde artists the Academy rejected. This constant cycle of establishing rules and then breaking them is what drives art forward.

It makes you wonder: what rigid rules of today’s art world will seem just as strange and surprising 200 years from now?

15-02 Academic Art – Nicolas Poussin

15-02 Notes on Nicolas Poussin

15-02 Podcast on Nicolas Possin produced by Google NotebookLM based on the notes

15-02 Nicolas Poussin Blog

Summarises the main themes, important ideas, and key facts presented in the the lecture notes on the life and work of Nicolas Poussin. These notes draw upon a range of publicly available resources and AI assistance to provide an overview of Poussin’s artistic journey, key works, and lasting influence.

Main Themes and Important Ideas:

- Biography and Early Influences:

- Born in Normandy to a noble but impoverished family, Poussin displayed remarkable early artistic talent despite parental opposition to a career in art. His early education included Latin, which later proved valuable in his study of classical texts.

- Defying his parents, he moved to Paris at eighteen and studied under minor masters. Crucially, he learnt significantly from studying engravings of Raphael and Giulio Romano.

- His move to Rome in 1624 at the age of 30 marked a pivotal point in his career. He resided there for most of his life, immersing himself in the works of Renaissance masters, particularly Raphael, and contemporary Baroque painters. Notably, he “famously detested Caravaggio’s style.”

- Poussin secured patronage from wealthy individuals, including Cardinal Francesco Barberini and Cassiano dal Pozzo, leading to commissions for religious, mythological, and historical paintings.

- Artistic Development and Style:

- Poussin’s style is characterised by clarity, logic, and order, reflecting his deep engagement with classical antiquity and Renaissance principles. His works often exhibit carefully arranged figures in frieze-like compositions, reminiscent of ancient Roman relief sculptures.

- He developed a meticulous working method, including the use of wax figures in miniature settings to perfect spatial relationships and formal balance before painting. This is highlighted in the discussion of “The Abduction of the Sabine Women”: “His meticulous working method for this painting involved arranging wax figures in a miniature theater-like box to perfect the spatial relationships and formal balance before committing to canvas.”

- While in Rome, his style evolved towards “greater austerity and intellectual rigour.”

- Later in life, he increasingly turned to landscape painting, imbuing natural scenes with classical and philosophical themes, as seen in “Landscape with the Ashes of Phocion”.

- Relationship with France:

- Between 1640 and 1642, Poussin reluctantly returned to Paris to serve as First Painter to King Louis XIII. However, he found court politics and the pressure to produce decorative works “contrary to his artistic vision caused him great distress.”

- He returned to Rome and preferred working for a smaller group of discerning collectors.

- Key Works and Their Significance:

- “The Death of Germanicus” (1627): This early major history painting, commissioned by Cardinal Barberini, “represents a pivotal moment in his career.” It demonstrates his emerging classical style with carefully arranged figures and emotional restraint, establishing a template for deathbed scenes for centuries to come.

- “The Triumph of David” (c.1631-1633): An early masterpiece showcasing Poussin’s “psychological insight into human emotion and gesture.” The painting captures a spectrum of reactions to David’s victory, arranged with architectural precision. X-ray analysis reveals his meticulous reworking of compositions.

- “The Abduction of the Sabine Women” (1633-1634): A dynamic and ambitious composition from his early Roman period, exemplifying his innovative approach to historical painting. His method involved arranging wax figures. It belonged to prominent figures like the French ambassador and Cardinal Richelieu, indicating his early recognition.

- “The Adoration of the Golden Calf” (1633-1634): A dramatic and complex biblical composition demonstrating his mastery of narrative clarity and dramatic tension. The arrangement of dancing figures reflects his study of ancient Roman reliefs. Its religious significance during the Counter-Reformation is noted.

- “A Dance to the Music of Time” (c.1634-1636): An enigmatic and philosophically rich allegorical work depicting the cyclical nature of human existence. The dancing figures represent the Seasons, set against a timeless landscape with memento mori symbols.

- “The Arcadian Shepherds (Et in Arcadia Ego)” (1637-1638): One of his most celebrated and influential works, meditating on mortality within an idealized pastoral setting. This second version of the theme shows his evolution towards greater classical restraint. The inscription “Et in Arcadia Ego” prompts contemplation of death’s presence even in paradise.

- “Landscape with the Ashes of Phocion” (1648): Represents Poussin’s mature period, balancing historical narrative with idealized landscape. It reflects Stoic thought and the contrast between nature’s permanence and human transience.

- “The Holy Family on the Steps” (1648): A harmonious and contemplative religious composition created during his mature period. His meticulous working method using wax models is highlighted. The painting is rich in symbolic content.

- “The Judgment of Solomon” (1649): An accomplished narrative painting demonstrating his mastery of classical principles and understanding of human psychology. Its political significance during a period of French instability is noted.

- “Blind Orion Searching for the Rising Sun” (1658): An ambitious and poetic late landscape, demonstrating remarkable technical precision despite his declining health. It integrates mythological narrative with meteorological subtext.

- “Spring (The Earthly Paradise)” (1660-1664): The first in his final “Four Seasons” series, representing his profound meditation on the relationship between human history and natural cycles. Despite severe physical limitations, the painting showcases extraordinary technical accomplishment.

- Legacy and Influence:

- Poussin left behind a “profound artistic legacy” despite having no children.

- He significantly influenced French artists such as Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, particularly during the Neoclassical period, who drew inspiration from his rational and disciplined approach.

- His influence extended even to modern artists like Paul Cézanne, who admired his structural clarity and compositional harmony.

- Today, he is recognised as the leading painter of the classical French Baroque style and one of the most important artists of the 17th century.

Conclusion:

My talk provides an introduction to Nicolas Poussin’s life and artistic contributions. It highlights his dedication to classical principles, his meticulous working methods, and his ability to infuse historical, mythological, and religious subjects with intellectual depth and emotional resonance. Poussin’s enduring influence on subsequent generations of artists underscores his pivotal role in the history of Western art.

15-03 Academic Art – William-Adolphe Bouguereau

15-03 Notes on William-Adolphe Bouguereau

A chat generated by Google NotebookLM based on my notes on Bouguereau