A social theory that developed from Charles’s Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. It was thought that our species could in future degenerate or was already on the path to degeneration. This led to

looking for characteristics of degeneracy in criminals and in the twentieth century it led to eugenics and the idea of a degenerate race and degenerate art. See Degeneration.

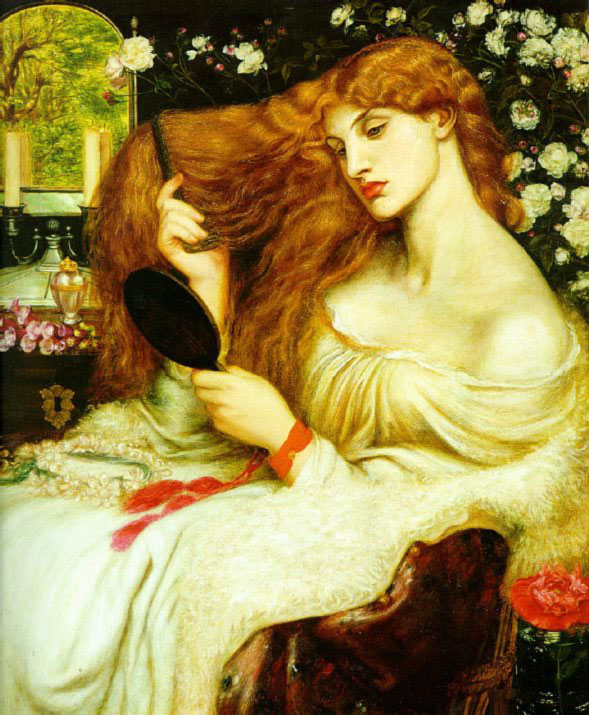

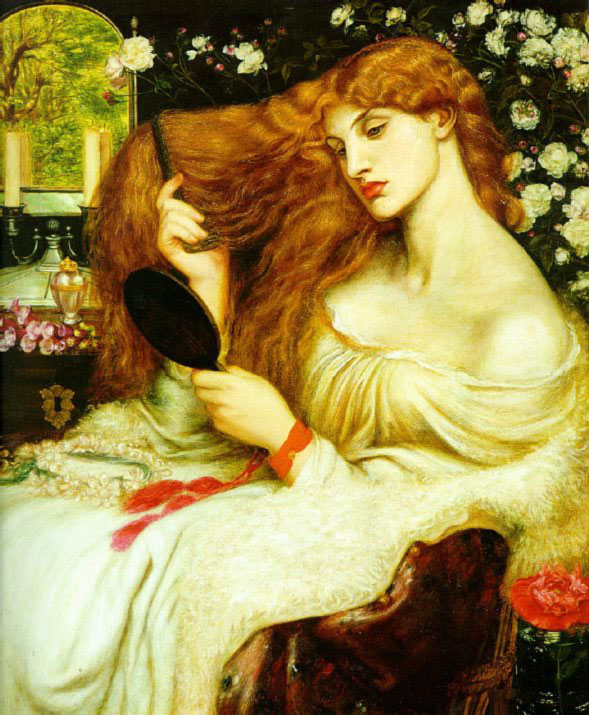

This section deals with the social circumstances surrounding the ideas of degeneracy and Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Lady Lilith (1864-73) will be used as a point of reference in unfolding these complex ideas that involve, sexuality, death, evolution and decadence.

Rossetti, Lady Lilith, 1864-73, for F. R. Leyland

We will start by considering one of Rossetti’s painting – Lady Lilith. See

Background

See the history of the Lilith legend. Basically according to Jewish legend Lilith was Adam’s first wife and they had children but separated because of Lilith’s independence. Adam asked God for another more amenable wife and He created Eve from his rib. Lilith changed into/used a snake to tempt Adam to break God’s commandment about not eating from the tree of knowledge. Lilith became the first witch and is known for breaking up families and stealing children.

Rossetti’s poem Lady Lilith, 1871

Of Adam’s first wife, Lilith, it is told

(The witch he loved before the gift of Eve,)

That, ere the snake’s, her sweet tongue could deceive,

And her enchanted hair was the first gold.

And still she sits, young while the earth is old,

And, subtly of herself contemplative,

Draws men to watch the bright net she can weave,

Till heart and body and life are in its hold.

The rose and poppy are her flowers; for where

Is he not found, O Lilith, whom shed scent

And soft-shed kisses and soft sleep shall snare?

Lo! as that youth’s eyes burned at thine, so went

Thy spell through him, and left his straight neck bent,

And round his heart one strangling golden hair.

Rossetti also wrote Eden Bower from Lilith’s point

of view where we, the reader are the snake. Buchanan says of the poen “the

reader feels a horrible sense of sliminess, as if he were handling a yellow

serpent or conger eel.”

Next consider one man’s view of the role of the Victorian woman. John Ruskin, “Woman” from

Lecture II of Queens’ Gardens in Sesame and Lilies. In particular,

|

This section is often referred to but less often quoted. It tells us a lot about Ruskin and his pathetic (‘to be pitied’) state of mind at this time. It also tells us a lot about the the fashionable stereotypes of men and women in the 1860s.

The Aesthetic Movement starting in about 1868 is described by this quote from Algernon Swinburne “A poet’s business is to write good verses, and by no means to redeem the age and remould society.” (Swinburne, Review of Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal (Flowers of Evil)).

It is also summarised by the well known phrase “art for art’s sake” (Swinburne, 1868).

Also consider Elizabeth Prettejohn’s comment:

“special integrity of the creative artist, dedicated to art alone, supplants the Ruskinian model of the artist who imitates God’s creation.”

Rossetti painted Lady Lilith between 1864 and 1873. Note she is not wearing a corset and her white wrap is carelessly falling from her shoulder exposing it and about to expose her breast. She is surrounded by white roses and there is a red poppy on the chair arm. The table has what look like foxgloves, two unlit candles and a second mirror reflecting a sunlit garden. It is painted in a

painterly style (‘painterly’ is a translation of Heinrich Wolfflin’s ‘malerisch’, a term he used to distinguish two types of painting, linear and painterly).

Holman Hunt called Rossetti’s female heads “women and flowers”.

Rossetti called Lady Lilith his toilet picture (meaning ‘toilette’) in a letter to his mother, perhaps referring to Titian’s painting.

Titian Young Woman at her Toilet, 1515, Louvre

Rossetti also said in his letter it was a ‘piece of colour’ and ‘full of material’ and ‘It’s colour will be chiefly white and silver with a mass of golden hair’.

He later changed the title to Body’s Beauty to distinguish it from another painting Sybilla Palmifera he called Soul’s Beauty, 1866-70. The Cumaean Sibyl was meant to have foretold the coming of Christ in Virgil’s Fourth Eclogue.

The original version was painted using Fanny Cornforth as model but at the request of his patron Leyland he repainted the head using Alexa Wilding as model. This is perhaps because by the 1860s the buxom Fanny was not fashionable and the fashion had changed to the angular, heavy-lidded looks of Alexa Wilding.

Rossetti, Woman Combing Her Hair, 1864 (Fanny Cornforth)

Rossetti, Worldly Beauty, 1867 (Fanny Cornforth)

Rossetti, Lady Lilith, 1864-73, face changed to that of Alexa Wilding for his patron F.R. Leyland

Fanny’s head perhaps sits more naturally on her body.

Rossetti believed he was

painting a modern day Lilith, he wrote in 1870:

“Lady [Lilith] . . . represents a Modern Lilith combing out her abundant golden hair and gazing on herself in the glass with that self-absorption by whose strange fascination such natures draw others within their own circle.” (Rossetti, W. M. ii.850, D.G. Rossetti’s emphasis)

J. B. Bullen in his book ‘The Pre-Raphaelite Body’ wrote:

The threat posed by Lilith in the literary and mythological accounts is translated by Rossetti into this act of self-contemplation [her gaze into the mirror], and that danger is given an added frission by the contemporaneity of the figure, a “Modern Lilith.” She has stepped out of the past and into the nineteenth century. She is to be found in the modern upper-class Victorian boudoir or bedroom, and is as potent an influence over the nineteenth- century male mind as she was over the ancient male mind. (136)

Rossetti drags her from the mythical past into the Victorian bedroom to make her relevant to contemporary social and moral issues.

The story of Lilith was first brought into the contemporary world by Goethe in his Faust.

This is from Wikipedia’s entry on Lilith:

In the earliest Romantic work, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 1808 work Faust Part I, Lilith makes another literary appearance, one that has been seen in nearly 600 years since the Zohar. This appearance is quite significant when compared to the ancient works, as Lilith begins to take on a new dimension and a more positive role.

The legends about Dr. Faustus may have begun about 1540. In most versions are his quests for forbidden and often hidden knowledge. During a “Walpurgis” Night scene of Faust by Goethe, Lilith makes one appearance:

FAUST:

Who’s that there?

MEPHISTOPHELES:

Take a good look.

Lilith.

FAUST:

Lilith? Who is that?

MEPHISTOPHELES:

Adam’s wife, his first. Beware of her.

Her beauty’s one boast is her dangerous hair.

When Lilith winds it tight around young men

She doesn’t soon let go of them again.

(1992 Greenberg translation, lines 4206-4211)

With her “ensnaring” sexuality, Goethe draws upon ancient legends of Lilith which associate her with Adam. Perhaps, more importantly, is the identifying marker of Lilith, her long, ensnaring hair, a image recounted in more familiar ancient tales. This image is the first “modern” literary mention of Lilith and continues to dominate throughout the nineteenth century. After Mephistopheles offers this warning to Faust, he then, quite ironically, encourages Faust to dance with

“the Pretty Witch”. Lilith and Faust engage in a short conversation, where Lilith recounts the days spent in Eden.FAUST: [Dancing with the young witch]

A lovely dream I dreamt one day

I saw a green-leaved apple tree,

Two apples swayed upon a stem,

So tempting! I climbed up for them.

THE PRETTY WITCH.

Ever since the days of Eden

Apples have been man’s desire.

How overjoyed I am to think, sir,

Apples grow, too, in my garden.

(1992 Greenberg translation, lines 4216- 4223)

Here, Goethe, chooses to elaborate on the Eden scene, focusing on the popular Lilith’s identity as the first wife of Adam rather than a child-killing and disease-bearing spirit or demon.

This brief mention is important, as it marks Lilith’s debut in modern literature. Additionally, her character for the most part is unnecessary, this establishes that Goethe’s intentions and reason in invoking her image and associations may differ.[16] It, also, suggests familiarity with the figure of Lilith. This text heavily influenced the later Romantic art and literature of Lilith and how she is often potrayed and continues to dominate representations throughout the 19th century.[16]

Goethe’s Faust was also the subject of painting:

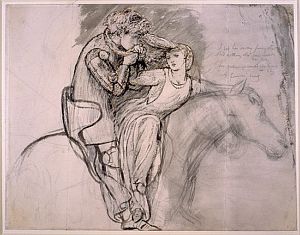

Delacroix, Faust with Margarete in Prison (detail), 1828

Holst, Fantasy Based on Goethe’s ‘Faust’, 1834

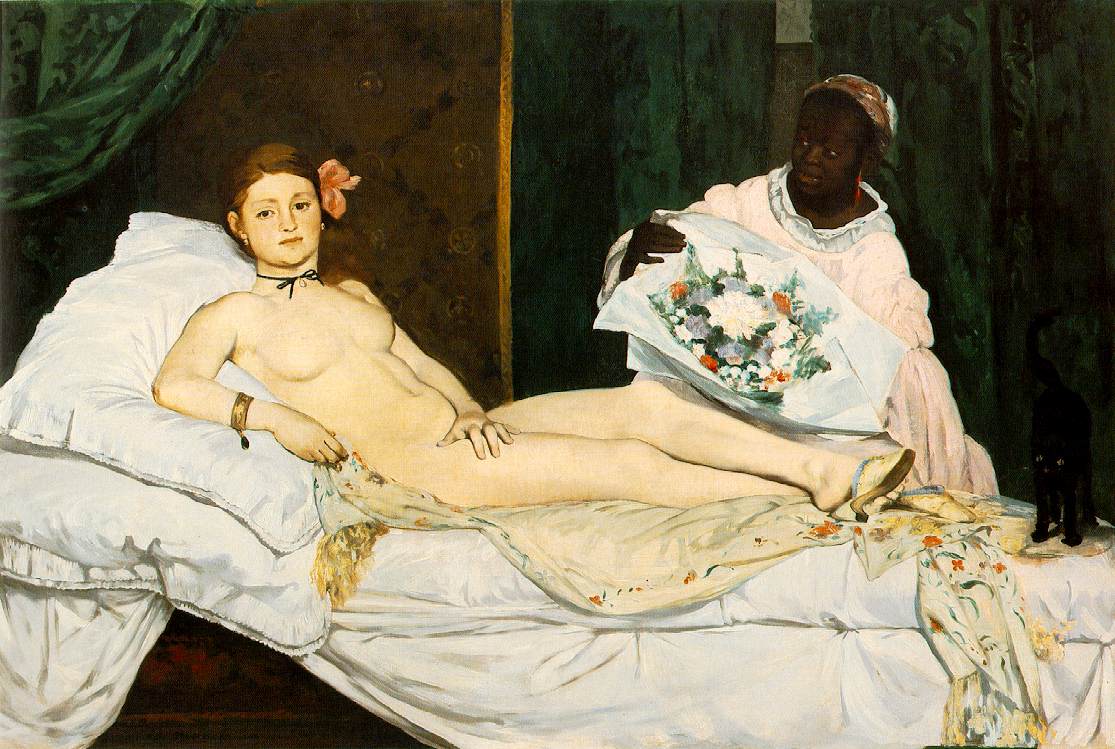

If we consider other paintings of the same period as Lady Lilith a controversial painting shown in France in 1865 was Manet’s Olympia.

Or perhaps more relevant to Lady Lilith Manet’s Nana.

Manet, Nana, 1877 (from Zola’s novel)

Are we looking at one aspect of capitalism, commodified beauty, an object of consumption. This may apply to Manet’s Olympia who is firmly part of the modern world but Lady Lilith is abstracted from her contemporary setting by the associations of ‘Lilith’.

Lilith is the most powerful of all female figures. She was created equal to Adam and did not participate in the Fall (in fact, disguised as a snake, she caused the Fall of man). She is therefore outside time, still in the Garden of Eden, all powerful and eternally antagonistic towards Adam, his family and all his future generations.

“She appears in the ardent languor of triumphant luxury and beauty…The haughty luxuriousness of the beautiful modern witch’s face, the tale of cold soul amid its charms, does not belie…the fires of a voluptuous physique”, Stephens on Lilith “Lilith…is the first strong-minded woman and the original advocate of woman’s rights”, Lyons letter to the Atheneum (owned by Rossetti) “Leonardo’s Mona Lisa ‘is older than the rocks among which she sits; like

a vampire, she hs been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave.” Pater, Leonardo, 1867

Note the combination of beauty and coldness, a coldness associated with death, vampires and the grave. This is the start of the concept we call the ‘femme fatale’, a woman who ensnares men with her beauty but who is cold and leads to their fall and death. It is the inverse of the fallen woman. A fallen woman is a women who is judged by man to have committed a social evil that cannot be forgiven and will result in her downfall through ‘moral gravity’ to her eventual death. The femme fatale seduces men and those who cannot resist are led to their fall and death.

Again, not like Manet’s Olympia, who looks in control of her own body but it is presented as a commodity, a body for sale.

The Aesthetes and Symbolists were concerned with:

- Suggestion (rather than statement), Baudelaire talks about the vague.

- Sensuality

- The use of symbols

- Synaesthetic effects

We can see the style of the Aesthetes in WHistler’s work.

Whistler, La Princesse du pays de la porcelaine, 1864

Whistler, Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room, 1876

“A figure for the autonomy of art, sufficient in its own beauty”, Prettejohn.

“a beautiful, almost haughty woman whose hand toys with her luxurious long hair as she gazes unsmiling at her own reflection in a mirror. She is engaged and satisfied with herself not with any male voyeur. She is sexual, dangerously seductive, and does not give the appearance of an acquiescent femininity which will be easily satisfied…Fear of and desire for ‘woman’ is incarnated in one painting. She is both sexual and selfish, gazing upon herself with satisfaction, symbolizing her rejection of ‘man.'”

James Ussher, Fantasies of Femininity: Reframing the Boundaries of Sex 1.997

There are many possibilities to consider, a woman, and in this Lady Lilith could be, for example:

- Empowered and independent

- A tease, luring men possibly into danger

- Simply available

“Narcissistic female figures, each with potentially fatal characteristics and “beauty gazing at itself”, Bullen

Keats La Belle DameSans Merci, 1819

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

Rossetti, La Belle Dame Sans Merci

Note how her hair is wound round his throat.

In Rossetti’s poem Eden Bower consider:

- Net/Snake

- Narrator/Hero

- Viewer/Innocent

- Beauty/Ugliness

- Beasts/Humans

- Good/Evil

- Transformations/Boundaries

It is not a dichotomy between good and evil but a dialogue.

Consider the lines:

‘Lend thy shape for the shame of Eden!

(And O the bower and the hour!)Is not the foe-God weak as the foeman

When love grows hate in the heart of a woman?

This implies that Lilith is stronger or as strong as God.

Beauty

Beauty is a mixture of the eternal and the transitory-the

eternal is the ‘abstraction’ of the particular-the

particular is made up of the fashions, morals and passions of the age.

Baudelaire

Rossetti’s Sonnets = ‘moment’s monument’ = Baudelaire ‘fleeting moment’

‘The perilous principle in the world being female in the first’, Rossetti on Lilith

“The threat posed by Lilith in the literarv and mythological accounts it translated by Rossetti into this act of self-contemplation [her gaze into the mirror] and that danger is given an added frission by the contemporaneity of the figure, a ‘Modern Lilith’. She has stepped out of the past and into the nineteenth century. She is to be found in the modern upper-class Victorian boudoir or bedroom, and is as potent an influence over the nineteenth-century

male mind as she was [imagined to be] over the ancient male mind.” Bullen

Charles Darwin In Descent of man Darwin wrote: “The chief distinction in the intellectual powers of the two sexes is shewn by man’s attaining to a higher eminence, in whatever he takes up, than can woman – whether requiring deep thought, reason, or imagination, or merely the use of the senses and hands” (Chapter 19, 1871 edition Darwin, Descent of Man – Chapter 19 – Secondary Sexual Characters of Man). Note the extreme and absolute terms used by Darwin. Darwin was straying outside his established facts at this point but his musings probably reflected the views of many Victorians. Even today we jump at conclusions regarding innate differences between man and women when it is very difficult to distinguish scientifically innate differences from cultural differences. In the eighteenth century the was “The Great Chain of Being” and Linnaeus Systema Naturae (General System of Nature), 1735, that grew from 11 pages to the classification of 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 plants.

In the nineteenth century there were many ideas regarding “evolution” (for example, Darwin’s grandfather had such ideas). This was not Darwin’s breakthrough. Darwin realised that there were always small differences between individuals in a species and some of these differences made they individuals that possessed them more likely to have more children. He also realised many more are born than survive and have children, it is a dangerous world. Finally, he realised our small differences are passed on to our children (although the way this is done was not worked out until Mendel) and as a result those individuals that have more children will pass on those differences. Over a long period of time most members of the species will be ancestors of those with such differences and will therefore posses such differences. Note I have written this without needing to use technical terms such as mutation, selection and evolution. Unfortunately a lack of understanding of the process and incorrect assumptions based on the word ‘evolution’ suggested to some that Darwin’s work

was concerned with progress and improvement.

The Theory of Evolution is not a theory that describes the gradual improvement and progress of living things leading eventually to the human race. In some ways the bacteria are the most highly evolved in that there are more of them in more locations than any other living thing. Evolution is blind, it is simply a mechanism that results in more of certain types of traits surviving because those individuals have more children.

Regarding the differences between the sexes Darwin said, in “The Descent of

Man”,

DIFFERENCE IN THE MENTAL POWERS OF THE TWO SEXES.

With respect to differences of this nature between man and woman, it is probable that sexual selection has played a highly important part. I am aware that some writers doubt whether there is any such inherent difference; but this is at least probable from the analogy of the lower animals which present other secondary sexual characters. No one disputes that the bull differs in disposition from the cow, the wild-boar from the sow, the stallion from the mare, and, as is well known to the keepers of menageries, the males of the larger apes from the females. Woman seems to differ from man in mental disposition, chiefly in her greater tenderness and less selfishness; and this holds good even with savages, as shewn by a well-known passage in Mungo Park’s Travels, and by statements made by many other travellers. Woman, owing to her maternal instincts, displays these qualities towards her infants in an eminent degree; therefore it is likely that she would often extend them towards her fellow-creatures. Man is the rival of other men; he delights in competition, and this leads to ambition which passes too easily into selfishness. These latter qualities seem to be his natural and unfortunate birthright. It is generally admitted that with woman the powers of intuition, of rapid perception, and perhaps of imitation, are more strongly marked than in man; but some, at least, of these faculties are characteristic of the lower races, and therefore of a past and lower state of civilisation. The chief distinction in the intellectual powers of the two sexes is shewn by man’s attaining to a higher eminence, in whatever he takes up, than can woman–whether requiring deep thought, reason, or imagination, or merely the use of the senses and hands. If two lists were made of the most eminent men and women in poetry, painting, sculpture, music (inclusive both

of composition and performance), history, science, and philosophy, with

half-a-dozen names under each subject, the two lists would not bear

comparison. We may also infer, from the law of the deviation from

averages, so well illustrated by Mr. Galton, in his work on ‘Hereditary

Genius,’ that if men are capable of a decided pre-eminence over women in

many subjects, the average of mental power in man must be above that of

woman.

Amongst the half-human progenitors of man, and amongst savages, there have

been struggles between the males during many generations for the possession

of the females. But mere bodily strength and size would do little for

victory, unless associated with courage, perseverance, and determined

energy. With social animals, the young males have to pass through many a

contest before they win a female, and the older males have to retain their

females by renewed battles. They have, also, in the case of mankind, to

defend their females, as well as their young, from enemies of all kinds,

and to hunt for their joint subsistence. But to avoid enemies or to attack

them with success, to capture wild animals, and to fashion weapons,

requires the aid of the higher mental faculties, namely, observation,

reason, invention, or imagination. These various faculties will thus have

been continually put to the test and selected during manhood; they will,

moreover, have been strengthened by use during this same period of life.

Consequently in accordance with the principle often alluded to, we might

expect that they would at least tend to be transmitted chiefly to the male

offspring at the corresponding period of manhood.

Now, when two men are put into competition, or a man with a woman, both

possessed of every mental quality in equal perfection, save that one has

higher energy, perseverance, and courage, the latter will generally become

more eminent in every pursuit, and will gain the ascendancy. (24. J.

Stuart Mill remarks (‘The Subjection of Women,’ 1869, p. 122), “The things

in which man most excels woman are those which require most plodding, and

long hammering at single thoughts.” What is this but energy and

perseverance?) He may be said to possess genius–for genius has been

declared by a great authority to be patience; and patience, in this sense,

means unflinching, undaunted perseverance. But this view of genius is

perhaps deficient; for without the higher powers of the imagination and

reason, no eminent success can be gained in many subjects. These latter

faculties, as well as the former, will have been developed in man, partly

through sexual selection,–that is, through the contest of rival males, and

partly through natural selection, that is, from success in the general

struggle for life; and as in both cases the struggle will have been during

maturity, the characters gained will have been transmitted more fully to

the male than to the female offspring. It accords in a striking manner

with this view of the modification and re-inforcement of many of our mental

faculties by sexual selection, that, firstly, they notoriously undergo a

considerable change at puberty (25. Maudsley, ‘Mind and Body,’ p. 31.),

and, secondly, that eunuchs remain throughout life inferior in these same

qualities. Thus, man has ultimately become superior to woman. It is,

indeed, fortunate that the law of the equal transmission of characters to

both sexes prevails with mammals; otherwise, it is probable that man would

have become as superior in mental endowment to woman, as the peacock is in

ornamental plumage to the peahen.

It must be borne in mind that the tendency in characters acquired by either

sex late in life, to be transmitted to the same sex at the same age, and of

early acquired characters to be transmitted to both sexes, are rules which,

though general, do not always hold. If they always held good, we might

conclude (but I here exceed my proper bounds) that the inherited effects of

the early education of boys and girls would be transmitted equally to both

sexes; so that the present inequality in mental power between the sexes

would not be effaced by a similar course of early training; nor can it have

been caused by their dissimilar early training. In order that woman should

reach the same standard as man, she ought, when nearly adult, to be trained

to energy and perseverance, and to have her reason and imagination

exercised to the highest point; and then she would probably transmit these

qualities chiefly to her adult daughters. All women, however, could not be

thus raised, unless during many generations those who excelled in the above

robust virtues were married, and produced offspring in larger numbers than

other women. As before remarked of bodily strength, although men do not

now fight for their wives, and this form of selection has passed away, yet

during manhood, they generally undergo a severe struggle in order to

maintain themselves and their families; and this will tend to keep up or

even increase their mental powers, and, as a consequence, the present

inequality between the sexes. (26. An observation by Vogt bears on this

subject: he says, “It is a remarkable circumstance, that the difference

between the sexes, as regards the cranial cavity, increases with the

development of the race, so that the male European excels much more the

female, than the negro the negress. Welcker confirms this statement of

Huschke from his measurements of negro and German skulls.” But Vogt admits

(‘Lectures on Man,’ Eng. translat. 1864, p. 81) that more observations are

requisite on this point.

Of course, we now know on many of these matters Darwin was wrong but the

quote has been given in full as it gives a good insight into Victorian thinking.

We can begin to understand how a link was made from this type of thinking to

nationalism and imperialism and the superiority of the European.

It led to the work of Francis

Galton and Patrick Geddes “The Evolution of Sex” (1889).

In art women as a less evolved state is picked up by Burne-Jones with his

painting of a mermaid pulling a sailor down to the depths. Degas’s pastels of

the 1880s can be seen as examining women as if they were animals.

However, in Rossetti’s possession when he died was a letter which appears to

be a reply to research he carried out on Lilith. The letter describes Lilith as

the first strong minded women and the original advocate of woman’s rights. We

also know that Barbara

Bodichon, an early campaigner for equal right of employment for women, and

an artist, was a friend of Rossetti.

Barbara Bodichon (1827-1891), The New Generation (Ye Newe Generation), pen and ink, 8″ x 10″

Degeneration

This set of beliefs grew out of a poor understanding of evolution. In 1882

Max Nordau (co-founder of

the World Zionist Organisation) wrote Degeneration, a book about what he saw as

the gradual deterioration of society resulting from a breakdown of family

values, a decadence and a world-weariness. He equated “mystic, symbolic and

‘decadent’ works” with disease. These ideas were picked up, particularly in the

Austro-Hungarian Empire, and led to a hysterical backlash against ‘degenerate’

art, for example, the conviction of Egon Schiele on pornography charges. The

ideas were later picked up by the Nazis who used the term Entartete Kunst

(Degenerate Art).

It was believed that degeneration was a disease and it was linked to

criminality, particularly sexual criminality and to studies of criminal

phrenology.

However, not everyone thought the same way and there was a rise in ‘New

Generation’ thinking alongside a rise in concerns about degeneration.

Burne-Jones based the following painting on an erotic poem by Swinburne called

Laus Veneris

(1866).

Burne Jones, Laus Veneris, 1870

The dress is marked in detail with a fine

round tool that gives it a texture. The women are white, cold, stone-like and

vampire-like. The story concerns

Tannhauser, shown outside,

who becomes involved with Venus, shown lounging. He realises the error of his

ways as he is meant to be on a crusade and returns to the Pope for forgiveness.

The Pope does not forgive him and says he will not forgive him until his staff

blossoms into flower. Tannhauser dejected returns to Venus where he languishes

never knowing that the Pope’s staff did burst into blossom.

There was a great deal written about vampires at the time and a lot of

anxiety about syphilis and death and the dangers of having sex with prostitutes.

Other Quotes

“Life should imitate Art” and “To burn always with this hard, gem-like

flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life.” Pater, History of the Renaissance (1873)

“If we had not welcomed the arts and invented this kind of cult of the

untrue, then the realization of general untruth and mendaciousness that now

comes to us through science-the realization that delusion and error are conditions of human knowledge and sensation

– would be utterly unbearable.

Honesty would lead us to nausea and suicide. Bitt now there is a counterforce

against our honesty that helps us avoid such consequences: art as the good will

to appearance” Friedrich

Nietzsche“The more abundant the hair; the more potent the sexual invitation implied in

is display. For folk, literary and psychoanalytic traditions agree that the

luxuriance of the hair is an index of vigorous sexuality, even of wantoness.”

Gitter ‘The Power of Women’s Hair in the Victorian Imagination’“a figure for the autonony of art, sufficient in its own beauty” Prettejohn on

mirrors“The chief distinction in the intellectual powers of the two sexes is shewn

by man’s it attaining a higher eminence, in whatever he takes up, than can women

-whether requiring deep thought, reason, or imagination, or merely the

use of the senses and hands.” Darwin

Texts

Bodichon, Englsih Woman’s Journal 1858

Drydsdale, Elements of Social Science 1859

John Ruskin, Sesame and Lilies 1865

Swinburne, Laus Veneris,1866

Dalton, The Comparative Worth of Different Races, 1869

Darwin, Descent of Man, 1871

Kraft Ebbing, Psychopathia Sexualis, 1889

Geddes & Thomson, The Evolution of Sex, 1889

Max Nordau, Degeneration, 1892

Rossetti’s Eden Bower, 1868 (companion poem to Lady Lilith)

It was Lilith the wife of Adam:

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Not a drop of her blood was human,

But she was made like a soft sweet woman.

Lilith stood on the skirts of Eden;

(And O the bower of the hour!)

She was the first that thence was driven;

With her was hell and with Eve was heaven.

In the ear of the Snake said Lilith :–

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

‘To thee I come when the rest is over;

A snake was I when thou wast my lover.

‘I was the fairest snake in Eden:

(And O the bower and the hour!)

By the earth’s will, new form and feature

Made me a wife for the earth’s new creature.

‘Take me thou as I come from Adam:

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Once again shall my love subdue thee;

The past is past and I am come to thee.

‘O but Adam was thrall to Lilith!

(And O the bower and the hour!)

All the threads of my hair are golden,

And there in a net his heart was holden.

‘O and Lilith was queen of Adam!

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

All the day and the night together

My breath could shake his soul like a feather.

‘What great joys had Adam and Lilith!–

(And O the bower and the hour!)

Sweet close rings of the serpent’s twining,

As heart in heart lay sighing and pining.

What bright babes had Adam and Lilith!–

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Shapes that coiled in the woods and waters,

Glittering sons and radiant daughters.

‘O thou God, the Lord God of Eden!

(And O the bower and the hour!)

Say, was this fair body for no man,

That of Adam’s flesh thou mak’st him a woman?

‘O thou Snake, the King-snake of Eden!

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

God’s strong will our necks are under,

But thou and I may cleave it in sunder.

‘Help, sweet Snake, sweet lover of Lilith!

(And O the bower and the hour!)

And let God learn how I loved and hated

Man in the image of God created.

‘Help me once against Eve and Adam!

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Help me once for this one endeavour,

And then my love shall be thine for ever!

‘Strong is God, the fell foe of Lilith:

(And O the bower and the hour!)

Nought in heaven or earth may affright him;

But join thou with me and we will smite him.

‘Strong is God, the great God of Eden:

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Over all he made he hath power;

But lend me thou thy shape for an hour!

‘Lend thy shape for the love of Lilith!

(And O the bower and the hour!)

Look, my mouth and cheek are ruddy,

And thou art cold, and fire is my body.

‘Lend thy shape for the hate of Adam!

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

That he may wail my joy that forsook him,

And curse the day when the bride-sleep took him.

‘Lend thy shape for the shame of Eden!

(And O the bower and the hour!)

Is not the foe-God weak as the foeman

When love grows hate in the heart of a woman?

‘Would’st thou know the heart’s hope of Lilith?

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Then bring thou close thine head till it glisten

long my breast, and lip me and listen.

‘Am I sweet, O sweet Snake of Eden?

(And O the bower and the hour!)

Then ope thine ear to my warm mouth’s cooing

And learn what deed remains for our doing.

‘Thou didst hear when God said to Adam:–

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

“Of all this wealth I have made thee warden;

Thou’rt free to eat of the trees of the garden:

‘”Only of one tree eat not in Eden;

(And O the bower and the hour!)

All save one I give to thy freewill,–

The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.”

‘O my love, come nearer to Lilith!

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

In thy sweet folds bind me and bend me,

And let me feel the shape thou shalt lend me!

‘In thy shape I’ll go back to Eden;

(And O the bower and the hour!)

In these coils that Tree will I grapple,

And stretch this crowned head forth by the apple.

‘Lo, Eve bends to the breath of Lilith!

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

O how then shall my heart desire

All her blood as food to its fire!

‘Lo, Eve bends to the words of Lilith!–

(And O the bower and the hour!)

“Nay, this Tree’s fruit,–why should ye hate it,

Or Death be born the day that ye ate it?

‘”Nay, but on that great day in Eden,

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

By the help that in this wise Tree is,

God knows well ye shall be as He is.”

‘Then Eve shall eat and give unto Adam;

(And O the bower and the hour!)

And then they both shall know they are naked,

And their hearts ache as my heart hath ached.

‘Aye, let them hide in the trees of Eden,

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

As in the cool of the day in the garden

God shall walk without pity or pardon.

‘Hear, thou Eve, the man’s heart in Adam!

(And O the bower and the hour!)

Of his brave words hark to the bravest:–

“This the woman gave that thou gavest.”

‘Hear Eve speak, yea, list to her, Lilith!

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Feast thine heart with words that shall sate it–

“This the serpent gave and I ate it.”

‘O proud Eve, cling close to thine Adam,

(And O the bower and the hour!)

Driven forth as the beasts of his naming

By the sword that for ever is flaming.

‘Know, thy path is known unto Lilith!

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

While the blithe birds sang at thy wedding,

There her tears grew thorns for thy treading.

‘O my love, thou Love-snake of Eden!

(And O the bower and the hour!)

O to-day and the day to come after!

Loose me, love,–give breath to my laughter!

‘O bright Snake, the Death-worm of Adam!

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Wreathe thy neck with my hair’s bright tether,

And wear my gold and thy gold together!

‘On that day on the skirts of Eden,

(And O the bower and the hour!)

In thy shape shall I glide back to thee,

And in my shape for an instant view thee.

‘But when thou’rt thou and Lilith is Lilith,

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

In what bliss past hearing or seeing

Shall each one drink of the other’s being!

‘With cries of “Eve!” and “Eden!” and “Adam!”

(And O the bower and the hour!)

How shall we mingle our love’s caresses,

I in thy coils, and thou in my tresses!

‘With those names, ye echoes of Eden,

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Fire shall cry from my heart that burneth,–

“Dust he is and to dust returneth!”

‘Yet to-day, thou master of Lilith,–

(And O the bower and the hour!)

Wrap me round in the form I’ll borrow

And let me tell thee of sweet to-morrow.

‘In the planted garden eastward in Eden,

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Where the river goes forth to water the garden,

The springs shall dry and the soil shall harden.

‘Yea, where the bride-sleep fell upon Adam,

(And O the bower and the hour!)

None shall hear when the storm-wind whistles

Through roses choked among thorns and thistles.

‘Yea, beside the east-gate of Eden,

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Where God joined them and none might sever,

The sword turns this way and that for ever.

‘What of Adam cast out of Eden?

(And O the bower and the hour!)

Lo! with care like a shadow shaken,

He tills the hard earth whence he was taken.

‘What of Eve too, cast out of Eden?

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

Nay, but she, the bride of God’s giving,

Must yet be mother of all men living.

‘Lo, God’s grace, by the grace of Lilith!

(And O the bower and the hour!)

To Eve’s womb, from our sweet to-morrow,

God shall greatly multiply sorrow.

‘Fold me fast, O God-snake of Eden!

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

What more prize than love to impel thee?

Grip and lip my limbs as I tell thee!

‘Lo! two babes for Eve and for Adam!

(And O the bower and the hour!)

Lo! sweet Snake, the travail and treasure,–

Two men-children born for their pleasure!

‘The first is Cain and the second Abel:

(Eden bower’s in flower.)

The soul of one shall be made thy brother,

And thy tongue shall lap the blood of the other.”

(And O the bower and the hour!)

(These are notes of a course given at Birkbeck College by Carol Jacobi in 2006/2007)