This section and the next deal with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Aesthetes.

An important book is J.B. Bullen’sThe Pre-Raphaelite Body, unfortunately £63 from Amazon (and surprisingly more second-hand from Abebooks and the cheapest I found was £35 from History Bookshop).

Rossetti, Beata Beatrix, 1864-70

This is an important painting, it is his last portrait of Lizzie Siddal and the first large oil painting he had done for some time. He was seeing Fanny Cornforth at this time and gathering disciples.

Lizzie died by drinking w hole bottle of laudanum. This form of opium was commonly used in Victorian England and even given to children to help them sleep. Lizzie was an experienced user of laudanum (i.e. a drug addict) and she died by drinking a whole bottle. This raises the question of why? Did she commit suicide? We know her movements on the evening, she had an early dinner with her husband Rossetti and a friend and Rossetti left to teach at the Working Men’s School. It has been speculated that Lizzie thought he had gone off with another women and committed suicide. The coroner recorded accidental death but there have been rumours of a suicide note that was destroyed. Alternatively, she may have been depressed as she had had a still birth and was carrying a second child, maybe she felt it had stopped moving in her womb?

Compare the above with the way drug overdoses are depicted today, typically a sprawling body and someone vomiting.

Rossetti arrived home about 9.00pm but did not realise straight away. When he could not wake her he called Brown from north London and a doctor. Lizzie never woke and died early the next morning.

The above painting is striking as it shows a move away from precision and attention to detail to a soft focus, dreamy other worldly atmosphere. Her expression is one of intense thought or spiritual contemplation. The white poppy carried by the red dove i a sign of oblivion.

The figure on the right could be Dante or Plato. The city in the background is Florence as we can see the Ponte Vecchio over the Arno in the background. The idea that it is Plato derives from the idea of Platonic love which Plato described in the Symposium (although Plato’s sacred love is that between an older man and a boy, love between men and women he thought were tainted by the desire for immortality through procreation).

Rossetti is showing us Beatrice, the beloved of Dante who died in 1290. Dante loved Beatrice from afar and she was the inspiration for his poetry. There are parallels between Rossetti’s life and that of Dante, Freud would later call this ‘uncanny’. Lizzie is also showing the signs of the ecstasy of a saint as in Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa (although it is unlikely that Rossetti knew this sculpture). Note the light behind her creating an

aureola and the bridge as a symbol of connection, possibly between earth and heaven. The red dove also has a halo and is seen as a messenger of love and the white poppy

is a symbol of sleep or death, remember the poppy is the source of opium and

therefore laudanum.

Everything is non-corporeal but the image is not that simple. She is also sexual, especially her parted lips with the phallic sundial pointing towards them and her exposed physical neck. It is an ambiguous image that combines the spiritual with the physical or it is possibly a synthesis between the two – lust combined with the higher forms of love.

Rossetti, Fazio’s Mistress, 1863

Celebrates the sensuous, physical nature of the body.

The title means ‘the kissed mouth’ and refers to a story by

Boccaccio in which

a beautiful women goes through many adventures that involve her in making love

to eight men. She cannot speak to any of them as she is a stranger abroad. She

returns home to become a nun and eventually marries a ninth good man as a

virgin. The kissed mouth (and other parts of her body) retain their youthfulness

and freshness as the moon returns anew each month. Rossetti is being challenging

and the painting celebrates Fanny’s beauty.

Holman Hunt criticized the painting and equated it with pornography although

he painted Il Dolce Far Niente in 1860 which was criticized as being to

sensual.

Holman Hunt, Il Dolce Far Niente, 1860

Rossetti introduces the idea of a storyless painting and a timeless setting

and timeless figures with a dreamy, abstracted woman.

Palma Vecchio, A Blonde Woman, possibly Flora, c. 1520 National Gallery, London

Rossetti, Venus Verticordia, 1864-8

Veronese, Marriage at Cana, 1563

Note: this is not the painting he got called in front of the Inquisition to defend.

“His love of richness and ornament got him into trouble with the Inquisition in a famous incident when he was taken to task for crowding a painting of the Last Supper with such irrelevant and irreverent figures as ‘a buffoon with a parrot on his wrist… a servant whose nose was bleeding… dwarfs and similar vulgarities’.

Veronese staunchly defended his right to artistic license:

I received the commission to decorate the picture as I saw fit. It is large and, it seemed to me, it could hold many figures.He was instructed to make changes, but the matter was resolved by changing the title of the picture to The Feast in the House of Levi (Accademia, Venice, 1573).” Webmuseum

Ruskin went through his de-conversion after seeing Veronese in Italy. Rossetti saw Veronese’s Marriage at Cana at the Louvre and described it as ‘flesh and blood’.

Rossetti was giving art a new role, that of pure pleasure, not ‘talkative art’ as Ruskin would call it. As Rossetti said, art should be free of all claptrap.

Rossetti was a precursor to aestheticism which is generally regarded as 1868-1901, ending with the trial of Oscar Wilde. The homoerotic Oxford don Walter Pater first published in 1867-8. So Bocca Baciata was a very early expression of these ideas in 1859. Theophile Gautier was writing about art for art’s sake doctrines from 1856 and the first to use the expression l’art pour l’art was Victor Cousin.

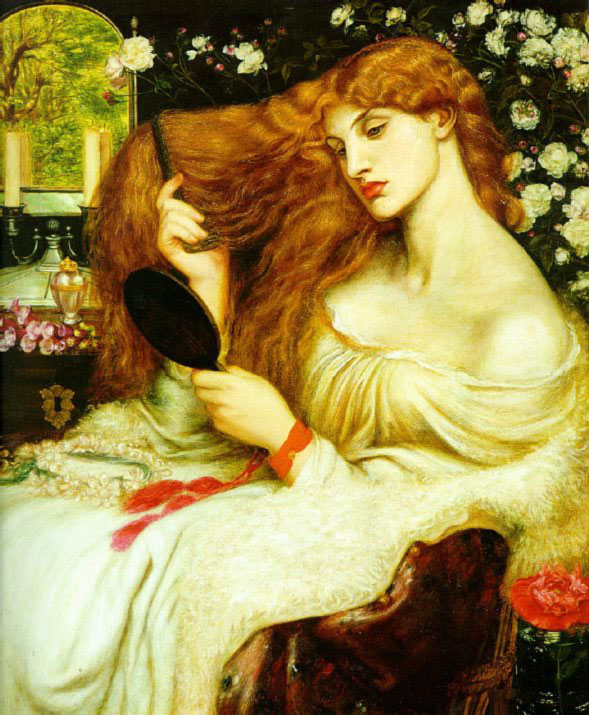

Rossetti, Lady Lilith, 1863-73

Lilith was created at the same time as Adam as his equal but as he rejected her Eve was made from his rib. Lilith is often presented as a witch and a stealer of children. Rossetti presents her as ‘body beautiful’.

Did Rossetti paint portraits of his models. He seems to use each model as a type of face but he generalises and as the years pass adds features from one model to another. Beginning with Lizzie and Annie Miller each new woman overlays the previous and the body becomes stylized. The stylized features include the hair, the mouth and the long neck. At Pre-Raphaelite parties women would waft around with loose hair and no girdle. It became very fashionable to dress this way amongst the more avant garde.

Rossetti changed the poem Jenny, an early version read:

Peril of mine, trouble of mine

Thine arms are bare and thy shoulders shine,

And through the kerchief and through the vest

Strikes the white of each breathing breast,

And the down is warm on thy velvet cheek,

And the thigh from thy rich side slopes oblique,

And thy lips are full, and thy brows are fair,

And the gold makes a daylight in thine hair

Which becomes in the 1870 version:

Why, Jenny, as I watch you there,–

For all your wealth of loosened hair,

Your silk ungirdled and unlac’d

And warm sweets open to the waist,

All golden in the lamplight’s gleam,–

You know not what a book you seem,Half-read by lightning in a dream!

We see the fetishisation of the female form, that is the concentration or fixation on a particular body part.

Rossetti’s women have been looked at in many ways:

- The Idealised Female Beauty. See Griselda Pollock, Vision and

Difference: Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art, in particular

Chapters 5 and 6, Woman as sign: psychoanalytic readings. - The Morbid or Diseased Body. Note the women’s deathly white skin, red

feverish lips and sunken eyes, all associated with illness. - The Powerful Body, or Femme Fatale. Note the prehensile, strong hands,

muscular shoulders and rounded sensual body that blends into the dress with

the often sharp, angular face. The femme fatale is a later term but an old idea of a women who attracts and ensnares hapless males to gain some villainous end.

In Lady Lilith note the red ribbon as a symbol for genitalia, a conventional

Venetian technique. Also note how she fills and overflows the rectangle and the

lock behind her, another Venetian symbol. The woman is shown in an interior with

the natural world glimpsed behind as in Holman Hunt’s Awakening Conscience.

It is difficult to work out the structure and anatomy of the women. Rossetti

is often criticized for his poor understanding of anatomy as he dropped out of

the Royal Academy life classes. However, by the end of his life his female

anatomy is good and by the end of his career he has worked out a way of painting

these women. In fact in a letter he describes it as a simple technique he has

worked out that he could teach to anyone.

Rossetti often worked in chalk like Degas. It is a technique that encourages

the aesthetic technique as colours are chosen rahter than mixed and it

accentuates boundaries. It also introduces a tactical element as the artist rubs

and touches the surface.

Rossetti, The Blessed Damozel, 1875-8

It is based on his poem of the same name and imagines the dead female lover

longing for her lover from heaven, Rossetti describes her breasts warming the

bar of heaven. Rossetti combines what are called sacred and physical love.

‘In each of its phases the debate about Pre-Raphaelitism was staged around the representation of the human body’ J. B. Bullen, The Pre-Raphaelite Body (1998)

‘strange disorder of the mind or eyes’, The Times, 1851

The Ascetic or ‘Primitive’ Body is shown in the Cyclographic drawings inspired by Northern European artists such as Memling. Note the ascetic body of the nun in Hughes Convent Thoughts.

‘our dreams of progress’, Westminster Review

James Collinson, The Renunciation of Queen Elizabeth of Hungary, 1850

Collinson was one of the original seven PRB and at one stage he was engaged

to Christina Rossetti. He converted from Catholicism to Anglicanism to marry her

but they could never agree on their religious views. This painting is based on

Charles Kingsley’s The Saint’s Tragedy and it unmasks the extreme Catholic

practices. When her children had grown she became a nun and renounced the world

but her confessor pushed her to greater and greater extremes and feats of

asceticism, for example, she was had to renounce ever seeing her children again.

So this painting shows the tension between spirituality and physicality.

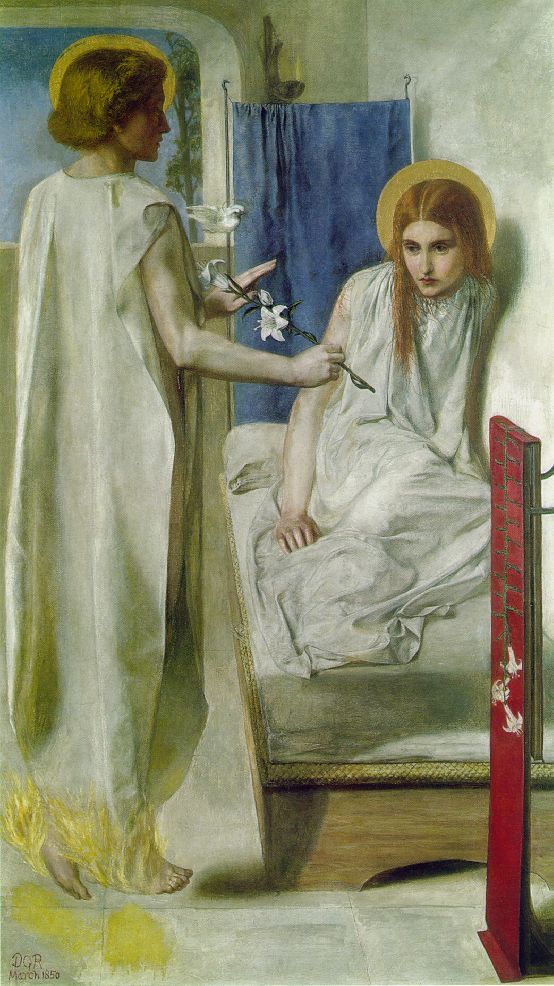

Compare Rossetti’s Found of 1854 and his Annunciation of 1850:

Rossetti, Ecce Ancilla Domini (Annunciation), 1849-50

They are not as far apart as they at first appear. The sensual, the material

or the spiritual or all three combined. Consider the sensuality of Gabriel, his

muscular arm and open smock. The lily he holds is almost a spear pointing and

continued through the crease of her nightdress. It creates a dialog between

physicality and spirituality.

Conventionally they are both in profile but Rossetti shows the Virgin Mary

facing us so we are brought into the action.

Found has a tension set up by country v. town, plain v. pretty (pretty

clothes were often a sign of a prostitute). Fanny Cornforth was unrepentant of

her chosen lifestyle as a prostitute and she saved enough money to buy a pub

which she ran for the rest of her life.

The Ascetic Body, the Material Body and the Aesthetic Body were in dialog

through Rossetti’s life and they cannot be divided.

Hunt, Isabella and the Pot of Basil, 1876

Morbid physicality, from her toenails to the rotting head of her former lover

in the pot.

The Auto-Erotic Body

‘an inner standing point’, Rossetti

Bullen’s idea of the auto-erotic body:

“the centre of … discourse lies not in the response of male sexuality to attractions, but in the ambiguity, fantasmagoric, and troubling responses

within the libido itself…narcissistic’, Bullen of Jenny

As the narrator spends the night with Jenny sleeping in his lap his thoughts

move through lust, guilt and greed. It is a series of unresolved responses.

We should remember that Rossetti’s poem Jenny was first written in 1848 and he put it to one side and came back to it in 1857. This was the period of the Contagious

Diseases Act (1864, 66 and 69) and the Divorce Act so there was a lot of

discussion of the body and issues of prostitution and disease. In 1860 he

presented the poem to Ruskin for comments, then Lizzie died in 1862 by

drinking laudanum and Rossetti as a gesture buried the poem with her body. She

was disinterred in 1869 specifically to retrieve the poem (he had contacts with

the Home Secretary and received permission) and he published in 1870 to general

acclaim (although all the reviewers were friends of his). One critic Robert Buchanan

published an adverse article, later a pamphlet, called The Fleshly School of

Poetry. Rossetti was very sensitive to any criticism and this could have

started his long decline and drug taking (a sleeping mixture called chloral with

whisky, commonly called a ‘Mickey Finn’ and used to render people unconscious) to his death in 1882.

Rossetti paints women but the women are himself. Remember in his story in Germ called Body and Soul the soul of the male artist is a women. Rossetti combines the spiritual, sexual, venal and lustful.

The National Body

- England was regarded as a body.

- Impressionism was seen by some as ‘a disease blown from abroad.’

- Gothic Revivalism was associated with Catholicism.

- Catholicism was associated with asceticism.

- Asceticism was associated with poverty.

- Poverty was associated with the Irish.

- The Irish were associated with vagrants.

- Vagrants were associated with cholera and disease.

Quotations

Proserpine

Afar away the light that brings cold cheer

Unto this wall, – one instant and no more

Admitted at my distant palace-door

Afar the flowers of Enna from this drear

Dire fruit, which, tasted once, must thrall me here.

Afar those skies from this Tartarean grey

That chills me: and afar how far away,

The nights that shall become the days that were.Afar from mine own self I seem, and wing

Strange ways in thought, and listen for a sign:

And still some heart unto some soul doth pine,

0, Whose sounds mine inner sense in fain to bring,

Continually together murmuring) —

‘Woe me for thee, unhappy Proserpine’.Rossetti

She is represented in a gloomy corridor of her palace, with the fatal fruit in

her hand. As she passes, a gleam strikes on the wall behind her from some inlet

suddenly opened, and admitting for a moment the sight of the upper world; and

she glances furtively towards it, immersed in thought. The incense-burner stands

beside her as the attribute of goddess. The ivy branch in the background may be

taken as a symbol of clinging memoryRossetti

Mary Magdalene at the door of Simon the Pharisee, 1858

Oh loose me! $eest thou not my Bridegroom’s face

That draws me to Him? For his feet my kiss,

My hair, my tears He craves today: – and oh!

What words can tell what other day and place

Shall see me clasp these blood-stained feet of His?

He needs me, calls me, loves me: let me go!Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1858

Christ’s profile was based upon the features of Rossetti’s fellow artist Edward

Burne-Jones. The face of the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne has been recognised in the young lover who tries to hold Mary back. Mary herself is based upon a great beauty of the day, the actress Ruth Herbert. Here we see the moment of her conversion, viewed incredulously by a crowd of revellers as she pulls a garland of roses from her long, flowing hair. Behind her a procession approaches from the distance. Women dance, men play musical instruments, a couple kiss as they enter a doorway. In the foreground three people stare up at Mary. On the left a beggar girl holding a bowl watches the glamorous figure ascend the stairs, upon which a finely dressed young woman kneels, her hand pressed against the wall to block Mary’s way. A young man stands immediately beneath her, dressed in a richly decorated cape, his head festooned with roses. He puts his hand upon Mary’s foot and knee to further impede her progress. In a letter to a patron, Rossetti explained that this man is Mary’s lover, her intended partner at the luxurious banquet in the house at the left of the drawing. The Magdalene’s attention, however, is entirely focused upon the other side of the picture. Within the doorway at the top of the stairs, a jowly, rather sour-looking man frowns out at her. This is the Pharisee Simon who has invited Christ into his house for dinner and debate. Behind him stands a serving girl, a steaming dish held aloft.

Entirely separated from the rest of the picture is the object of Mary’s urgent ascent: Christ, whose radiant head is visible through a window, returning Mary’s smitten gaze.

The Feast in the House of Simon:

The story of the feast in the house of Simon the Pharisee is told at Luke 7, 36

– 50. A Pharisee was a member of a strict Jewish sect and it is clear from

Luke’s narrative that Simon has invited Jesus to his house to challenge him on

points of Jewish law. In Rossetti’s drawing he is the archetypal hypocrite. We

see him visible just inside the doorway of his house, disapproving of the

revelry going on outside, and yet lavishly dressed and waited upon by a serving

girl.

In Luke’s account the woman who anoints Christ’s feet is not referred to by name

but from an early stage was identified as Mary Magdalene.

‘And one of the Pharisees desired of him that he would eat with him. And he went

into the Pharisee’s house, and sat down to meat.And, behold, a woman in the city, which was a sinner, when she knew that Jesus

sat at meat in the Pharisee’s house, brought an alabaster box of ointment, And

stood at his feet behind him weeping, and began to wash his feet with tears, and

did wioe them with the hairs of her head, and kissed his feet, and anointed them

with ointment.Now when the Pharisee which had bidden him saw it, he spake

within himself saying, This man, if he were a prophet, would have known who and

what manner of woman this is that toucheth him: for she is a sinner.And Jesus

answering said unto him, Simon, I have somewhat to say unto thee. And he saith,

Master, say on.There was a certain creditor which had two debtors: the one owed

five hundred pence, and the other fifty. And when they had nothing to pay, he

frankly forgave them both. Tell me therefore which of them will love him most?Simon answered and said, I suppose that he, to whom he forgave most. And he said

unto him, Thou hast rightly judged. And he turned to the woman, and said unto

Simon, Seest thou this woman? I entered into this house, thou gavest me no water

for my feet: but she hath washed my feet with tears, and wiped them with the

hairs of her head.Thou gavest me no kiss: but this woman since I came in hath

not ceased to kiss my feet. My head with oil thou didst not anoint: but this

woman hath anointed my feet with ointment. Wherefore I say unto thee, Her sins,

which are many, are forgiven: for she loved much: but to whom little is

forgiven, the same loveth little.And he said unto her, Thy sins are forgiven.

And they that sat at meat with him, began to say within themselves, Who is this

that forgiveth sins also? And he said to the woman, Thy faith hath saved thee;

go in peace.

Symbols from Medieval and Renaissance art and reinforce the theme of repentance

within the picture:

- Flanking the door to which Mary is ascending are two vases

containing flowers. At Mary’s left are three lilies, traditional symbols of

purity and virginity. In Annunciation scenes, there are often lilies present as

the archangel Gabriel tells the Virgin Mary that she is miraculously carrying

the son of God. In Domenic Veneziano’s panel from c. 1445, left, [11061, the

angel holds three lilies as he kneels before the Virgin. The implication in

Rossetti’s picture then, is that Mary Magdalene is turning towards a life of

purity. She sheds roses from her hair, flowers traditionally associated with

Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love. - To Mary’s right a second vase contains three sunflowers. These flowers, which

always turn their heads towards the sun, resemble Mary who has turned her back

on the revelry and is transfixed by the radiant head of Christ. - The fawn that nibbles at the vine beneath the window through which we see

Christ, also reflects Mary’s change of heart. It alludes to the opening of Psalm

42: ‘As the hart panteth after the waterbrooks, so panteth my soul after thee,

oh God.’ - The vine at which the fawn nibbles is an ancient symbol for Christ and the

Church. In the Gospel of John, 15, 1, Christ himself says, ‘I am the real vine.’ - Even the chickens pecking around the feet of the beggar girl were given a

Biblical significance by Rossetti who in a letter explained that they give a

kind of equivalent to Christ’s words: ‘Yet the dogs under the table eat of the

children’s crumbs.’ - Rossetti was in fact confused, for those words are spoken in Mark’s Gospel not

by Christ, but by a woman whom has come to him on behalf of her possessed

daughter.

Jenny

Vengeance of Jenny’s case! Fie on her! Never name her,

child!”Lazy laughing languid Jenny,

Fond of a kiss and fond of a guinea,

Whose head upon my knee to-nightRests for a while, as if grown light

With all our dances and the soundTo which the wild tunes spun you round:

Fair Jenny mine, the thoughtless queenOf kisses which the blush between

Could hardly make much daintier;Whose eyes are as blue skies, whose hair

Is countless gold incomparable:Fresh flower, scarce touched with signs that tell

Of Love’s exuberant hotbed:–Nay,Poor flower left torn since yesterday

Until to-morrow leave you bare;Poor handful of bright spring-water

Flung in the whirlpool’s shrieking face;Poor shameful Jenny, full of grace

Thus with your head upon my knee;–Whose person or whose purse may be

The lodestar of your reverie?This room of yours, my Jenny, looks

A change from mine so full of books,Whose serried ranks hold fast, forsooth,

So many captive hours of youth,–The hours they thieve from day and night

To make one’s cherished work come right,And leave it wrong for all their theft,

Even as to-night my work was left:Until I vowed that since my brain

And eyes of dancing seemed so fain,My feet should have some dancing too:–

And thus it was I met with you.Well, I suppose ’twas hard to part,

For here I am. And now, sweetheart,You seem too tired to get to bed.

It was a careless life I led

When rooms like this were scarce so strangeNot long ago. What breeds the change,–

The many aims or the few years?

Because to-night it all appears.Something I do not know again.

The cloud’s not danced out of my brain,–

The cloud that made it turn and swimWhile hour by hour the books grew dim.

Why, Jenny, as I watch you there,–For all your wealth of loosened hair,

Your silk ungirdled and unlac’dAnd warm sweets open to the waist,

All golden in the lamplight’s gleam,–You know not what a book you seem,

Half-read by lightning in a dream!How should you know, my Jenny? Nay,

And I should be ashamed to say:–Poor beauty, so well worth a kiss!

But while my thought runs on like thisWith wasteful whims more than enough,

I wonder what you’re thinking of.If of myself you think at all,

What is the thought?–conjectural

On sorry matters best unsolved?–Or inly is each grace revolved

To fit me with a lure?–or (sad

To think!) perhaps you’re merely gladThat I’m not drunk or ruffianly

And let you rest upon my knee.For sometimes, were the truth confess’d,

you’re thankful for a little rest,–Glad from the crush to rest within,

Form the heart-sickness and the dinWhere envy’s voice at virtue’s pitch

Mocks you because your gown is rich;And from the pale girl’s dumb rebuke,

Whose ill-clad grace and toil-worn lookProclaim the strength that keeps her weak

And other nights than yours bespeak;And from the wise unchildish elf,

To schoolmate lesser than himselfPointing you out, what thing you are:–

Yes, from the daily jeer and jar,From shame and shame’s outbraving too,

Is rest not sometimes sweet to you?–But most from the hatefulness of man

Who spares not to end what he began,Whose acts are ill and his speech ill,

Who, having used you at his will,Thrusts you aside, as when I dine

I serve the dishes and the wine.Well, handsome Jenny mine, sit up,

I’ve filled our glasses, let us sup,And do not let me think of you,

Lest shame of yours suffice for two.What, still so tired? Well, well then, keep

Your head there, so you do not sleep;But that the weariness may pass

And leave you merry, take this glass.Ah! lazy lily hand, more bless’d

If ne’er in rings it had been dress’dNor ever by a glove conceal’d!

Behold the lilies of the field,

They toil not neither do they spin;(So doth the ancient text begin,–

Not of such rest as one of theseCan share.) Another rest and ease

Along each summer-sated path

From its new lord the garden hath,Than that whose spring in blessings ran

Which praised the bounteous husbandman,Ere yet, in days of hankering breath,

The lilies sickened unto death.What, Jenny, are your lilies dead?

Aye, and the snow-white leaves are spreadLike winter on the garden-bed.

But you had roses left in May,–

They were not gone too. Jenny, nay,But must your roses die, and those

Their purfled buds that should unclose?Even so; the leaves are curled apart,

Still red as from the broken heart,And here’s the naked stem of thorns.

Nay, nay, mere words. Here nothing warns

As yet of winter. Sickness hereOr want alone could waken fear,–

Nothing but passion wrings a tear.Except when there may rise unsought

Haply at times a passing thoughtOf the old days which seem to be

Much older than any history

That is written in any book;When she would lie in fields and look

Along the ground through the blown grass,And wonder where the city was,

Far out of sight, whose broil and baleThey told her then for a child’s tale.

Jenny, you know the city now.

A child can tell the tale there, howSome things which are not yet enroll’d

In market-lists are bought and soldEven till the early Sunday light,

When Saturday night is market-nightEverywhere, be it dry or wet,

And market-night in the Haymarket.

Our learned London children know,Poor Jenny, all your mirth and woe;

Have seen your lifted silken skirtAdvertize dainties through the dirt;

Have seen your coach-wheels splash rebukeOn virtue; and have learned your look

When, wealth and health slipped past, you stareAlong the streets alone, and there,

Round the long park, across the bridge,The cold lamps at the pavement’s edge

Wind on together and apart,A fiery serpent for your heart.

Let the thoughts pass, an empty cloud!

Suppose I were to think aloud,–What if to her all this were said?

Why, as a volume seldom read

Being opened halfway shuts again,So might the pages of her brain

Be parted at such words, and thenceClose back upon the dusty sense.

For is there hue or shape defin’dIn Jenny’s desecrated mind,

Where all contagious currents meet,

A lethe of the middle street?Nay, it reflects not any face,

Nor sound is in its sluggish pace,But as they coil those eddies clot,

And night and day remember not.Why, Jenny, you’re asleep at last!–

Asleep, poor jenny, hard and fast,–So young and soft and tired; so fair,

With chin thus nestled in your hair,Mouth quiet, eyelids almost blue

As if some sky of dreams shone through!Just as another woman sleeps!

Enough to throw one’s thoughts in heapsOf doubt and horror,–what to say

Or think,–this awful secret sway,The potter’s power over the clay!

Of the same lump (it has been said)For honour and dishonour made,

Two sister vessels. Here is one.My cousin Nell is fond of fun,

And fond of dress, and change, and praise,So mere a woman in her ways:

And if her sweet eyes rich in youth

Are like her lips that tell the truth,My cousin Nell is fond of love.

And she’s the girl I’m proudest of.Who does not prize her, guard her well?

The love of change, in cousin Nell,Shall find the best and hold it dear:

The unconquered mirth turn quieterNot through her own, through others’ woe

The conscious pride of beauty glowBeside another’s pride in her,

One little part of all they share.For Love himself shall ripen these

In a kind soil to just increaseThrough years of fertilizing peace.

Of the same lump (as it is said)

For honour and dishonour made,

Two sister vessels. Here is one.It makes a goblin of the sun.

So pure,–so fall’n! How dare to think

Of the first common kindred link?Yet, Jenny, till the world shall burn

It seems that all things take their turn;And who shall say but this fair tree

May need, in changes that may be,Your children’s children’s charity?

Scorned then, no doubt, as you are scorn’d!Shall no man hold his pride forewarn’d

Till in the end, the Day of Days,At Judgment, one of his own race,

As frail and lost as you, shall rise,–His daughter, with his mother’s eyes?

How Jenny’s clock ticks on the shelf!

Might not the dial scorn itselfThat has such hours to register?

Yet as to me, even so to her

Are golden sun and silver moon,In daily largesse of earth’s boon,

Counted for life-coins to one tune.And if, as blindfold fates are toss’d,

Through some one man this life be lost,Shall soul not somehow pay for soul?

Fair shines the gilded aureole

In which our highest painters place

Some living woman’s simple face.And the stilled features thus descried

As Jenny’s long throat droops aside,–The shadows where the cheeks are thin,

And pure wide curve from ear to chin,–With Raffael’s or Da Vinci’s hand

To show them to men’s souls, might stand,Whole ages long, the whole world through,

For preachings of what God can do.What has man done here? How atone,

Great God, for this which man has done?And for the body and soul which by

Man’s pitiless doom must now complyWith lifelong hell, what lullaby

Of sweet forgetful second birth

Remains? All dark. No sign on earthWhat measure of god’s rest endows

The many mansions of his house.If but a woman’s heart might see

Such erring heart unerringly

For once! But that can never be.Like a rose shut in a book

In which pure women may not look,

For its base pages claim controlTo crush the flower within the soul;

Where through each dead rose-leaf that clings,Pale as transparent psyche-wings,

To the vile text, are traced such thingsAs might make lady’s cheek indeed

More than a living rose to read;So nought save foolish foulness may

Watch with hard eyes the sure decay;And so the life-blood of this rose,

Puddled with shameful knowledge, flowsThrough leaves no chaste hand may unclose:

Yet still it keeps such faded showOf when ’twas gathered long ago,

That the crushed petals’ lovely grain,The sweetness of the sanguine stain,

Seen of a woman’s eyes, must makeHer pitiful heart, so prone to ache,

Love roses better for its sake:–Only that this can never be:–

Even so unto her sex is she.Yet, Jenny, looking long at you,

The woman almost fades from view.A cipher of man’s changeless sum

Of lust, past, present, and to come,Is left. A riddle that one shrinks

To challenge from the scornful sphinx.Like a toad within a stone

Seated while time curmbles on;

Which sits there since the earth was curs’dFor Man’s transgression at the first;

Which, living through all centuries,Not once has seen the sun arise;

Whose life, to its cold circle charmed,The earth’s whole summers have not warmed;

Which always–whitherso the stoneBe flung–sits there, deaf, blind, alone;–

Aye, and shall not be driven outTill that which shuts him round about

Break at the very Master’s stroke,And the dust thereof vanish as smoke,

And the seed of Man vanish as dust:–Even so within this world is Lust.

Come, come, what use in thoughts like this?

Poor little Jenny, good to kiss,–You’d not believe by what strange roads

Thought travels, when your beauty goadsA man to-night to think of toads!

Jenny, wake up. . . . Why, there’s the dawn!And there’s an early waggon drawn

To market, and some sheep that jogBleating before a barking dog;

And the old streets come peering throughAnother night that London knew;

And all as ghostlike as the lamps.So on the wings of day decamps

My last night’s frolic. Glooms beginTo shiver off as lights creep in

Past the gauze curtains half drawn-to,And the lamp’s doubled shade grows blue,–

Your lamp, my Jenny, kept alight,Like a wise virgin’s, all one night!

And in the alcove coolly spreadGlimmers with dawn your empty bed;

And yonder your fair face I seeReflected lying on my knee,

Where teems with first foreshadowingsYour pier-glass scrawled with diamond rings.

And now without, as if some word

Had called upon them that they heard,The London sparrows far and nigh

Clamour together suddenly;

And Jenny’s cage-bird grown awakeHere in their song his part must take,

Because here too the day doth breakAnd somehow in myself the dawn

Among stirred clouds and veils withdrawnStrikes greyly on her. Let her sleep.

But will it wake her if I heapThese cushions thus beneath her head

Where my knee was? No,–there’s your bed,My Jenny, while you dream. And there

I lay among your golden hairPerhaps the subject of your dreams,

These golden coins.

For still one deemsThat Jenny’s flattering sleep confers

New magic on the magic purse,–Grim web, how clogged with shrivelled flies!

Between the threads fine fumes ariseAnd shape their pictures in the brain.

There roll no streets in glare and rain,Nor flagrant man-swine whets his tusk;

But delicately sighs in muskThe homage of the dim boudoir;

Or like a palpitating star

Thrilled into song, the opera-nightBreathes faint in the quick pulse of light;

Or at the carriage-window shineRich wares for choice; or, free to dine,

Whirls through its hour of health (divineFor her) the concourse of the Park.

And though in the discounted darkHer functions there and here are one,

Beneath the lamps and in the sunThere reigns at least the acknowledged belle

Apparelled beyond parallel.Ah Jenny, yes, we know your dreams.

For even the Paphian Venus seems

A goddess o’er the realms of love,When silver-shrined in shadowy grove:

Aye, or let offerings nicely placedBut hide Priapus to the waist,

And whoso looks on him shall see

An eligible deity.Why, Jenny, waking here alone

May help you to remember one,

Though all the memory’s long outwornOf many a double-pillowed morn.

I think I see you when you wake,

And rub your eyes for me, and shakeMy gold, in rising, from your hair,

A Danae for a moment there.Jenny, my love rang true! for still

Love at first sight is vague, untilThat tinkling makes him audible.

And must I mock you to the last,

Ashamed of my own shame,–aghast

Because some thoughts not born amissRose at a poor fair face like this?

Well, of such thoughts so much I know:In my life, as in hers, they show,

By a far gleam which I may near,A dark path I can strive to clear.

Only one kiss. Goodbye, my dear.

(These are notes of a course given at Birkbeck College by Carol Jacobi in 2006/2007)