This is a continuation of Heroes Sages Visionaries as it is concerned with self-fashioning. We find a range of self-portraits and portraits of the artist used for different purposes both public and private.

An artists public identity is constructed, performative, unstable, flexible and changeable.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Biography)

Even his name is constructed as he was christened Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti.

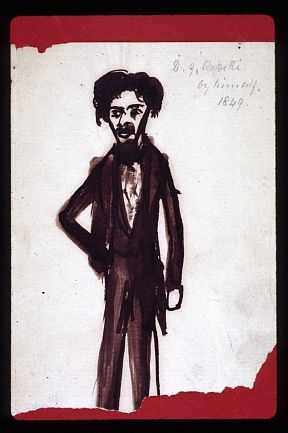

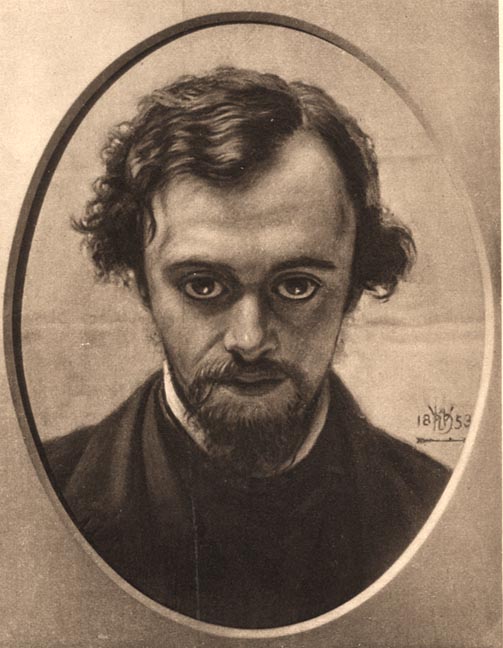

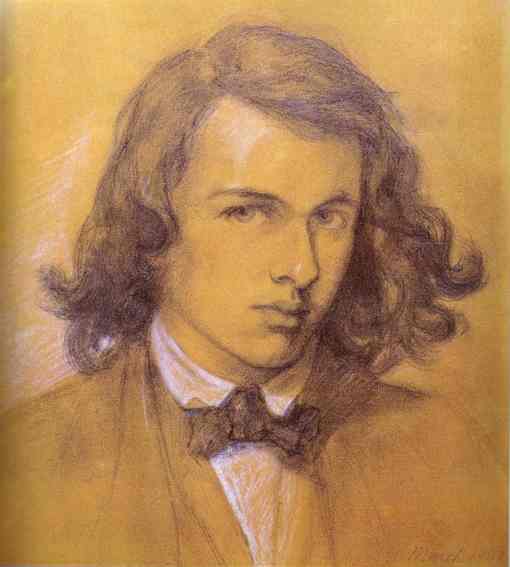

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Self-portrait, 1847

Rossetti often gave himself large eyes to stress his mind, the all seeing artist, and childlike innocence. Romantics borrowed the image of the child to emphasize their innocence and primal view of the world.

(See Robert Rosenblum, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko, Anne Higonnet, Pictures of Innocence: The History and Crisis of Ideal Childhood and in the 18th century Kate Retford, The Art of Domestic Life: Family Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century England)

In his earliest self-portrait he looks narcissistic, a bit shifty, with a highlighted brow to stress his intellect, dishevelled collar which accords with stories of his untidiness, idiosyncratic dressing, but to what extent was he creating himself.

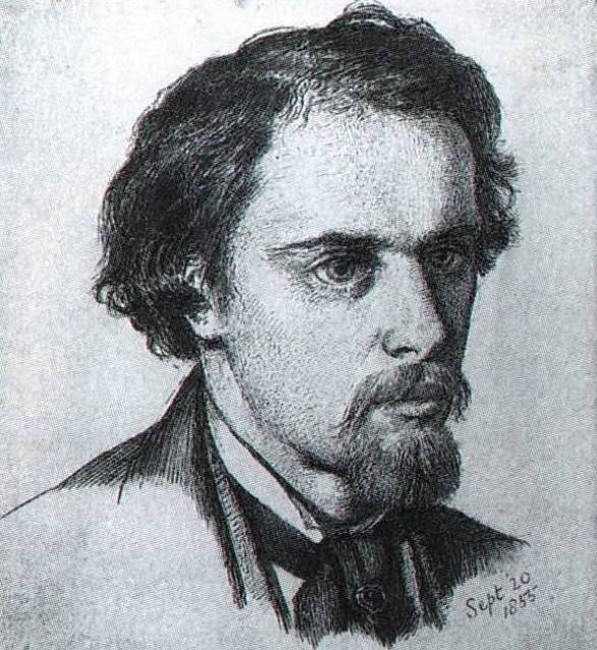

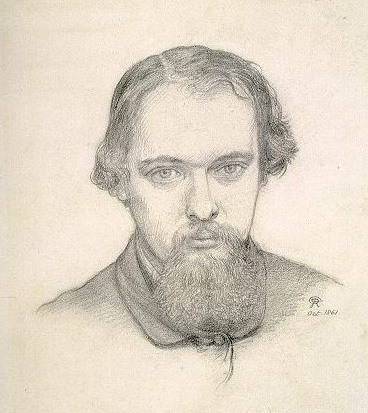

Rossetti, Self-portrait,1848-50

Rossetti sitting to Lizzie Siddal, Sept. 1853

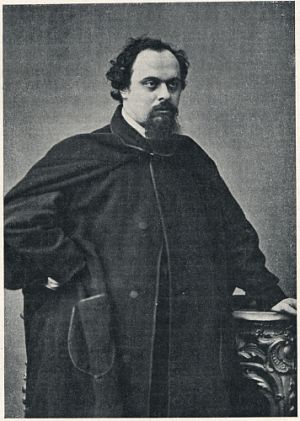

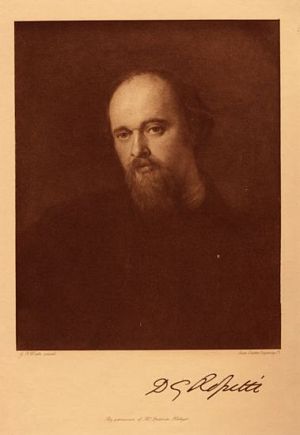

Rossetti sepia-tone, half-length portrait

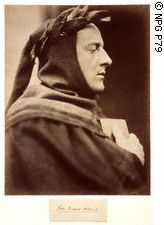

Lewis Carroll, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1863

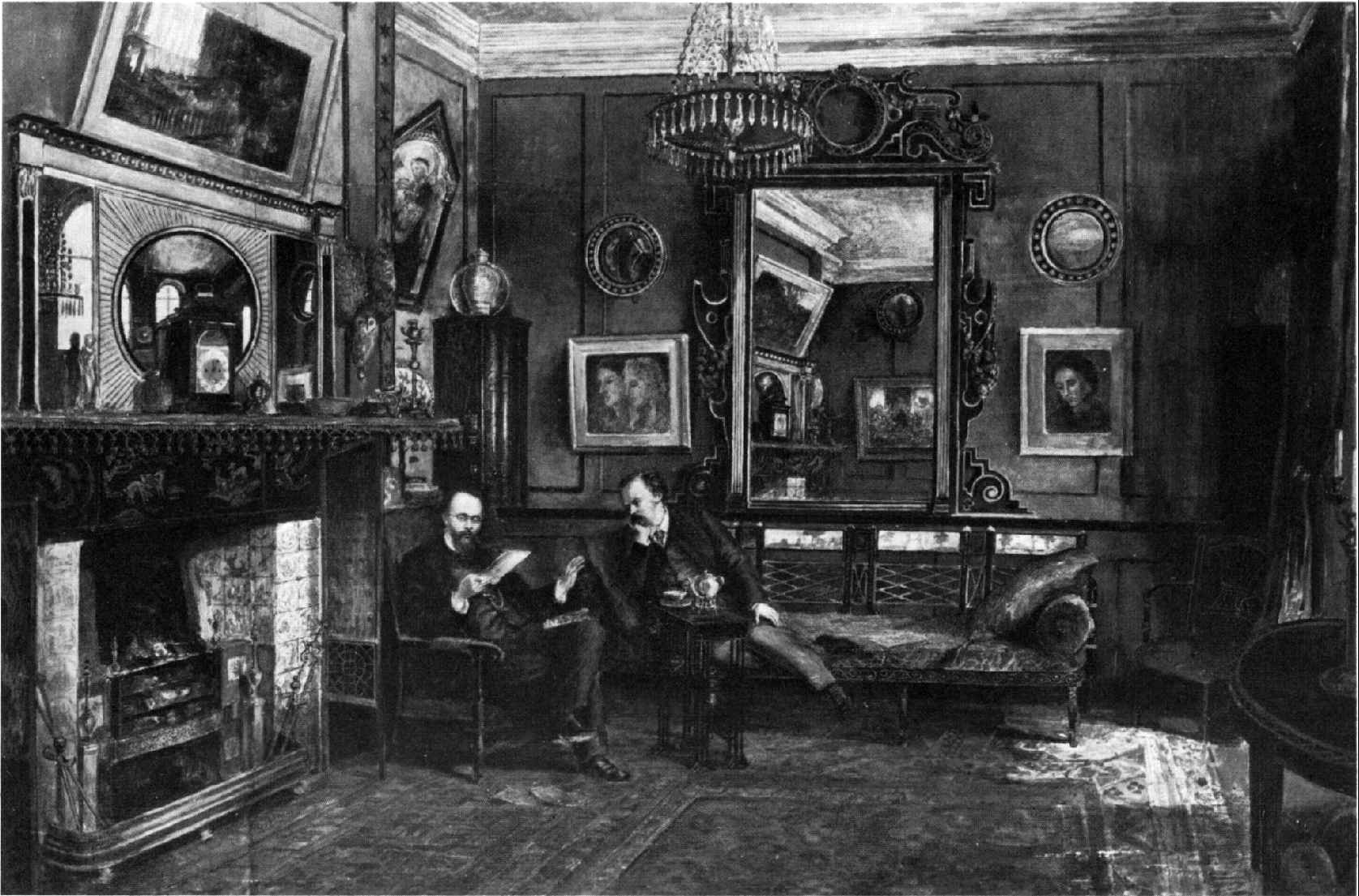

Rossetti at home in his Tudor House, 1882

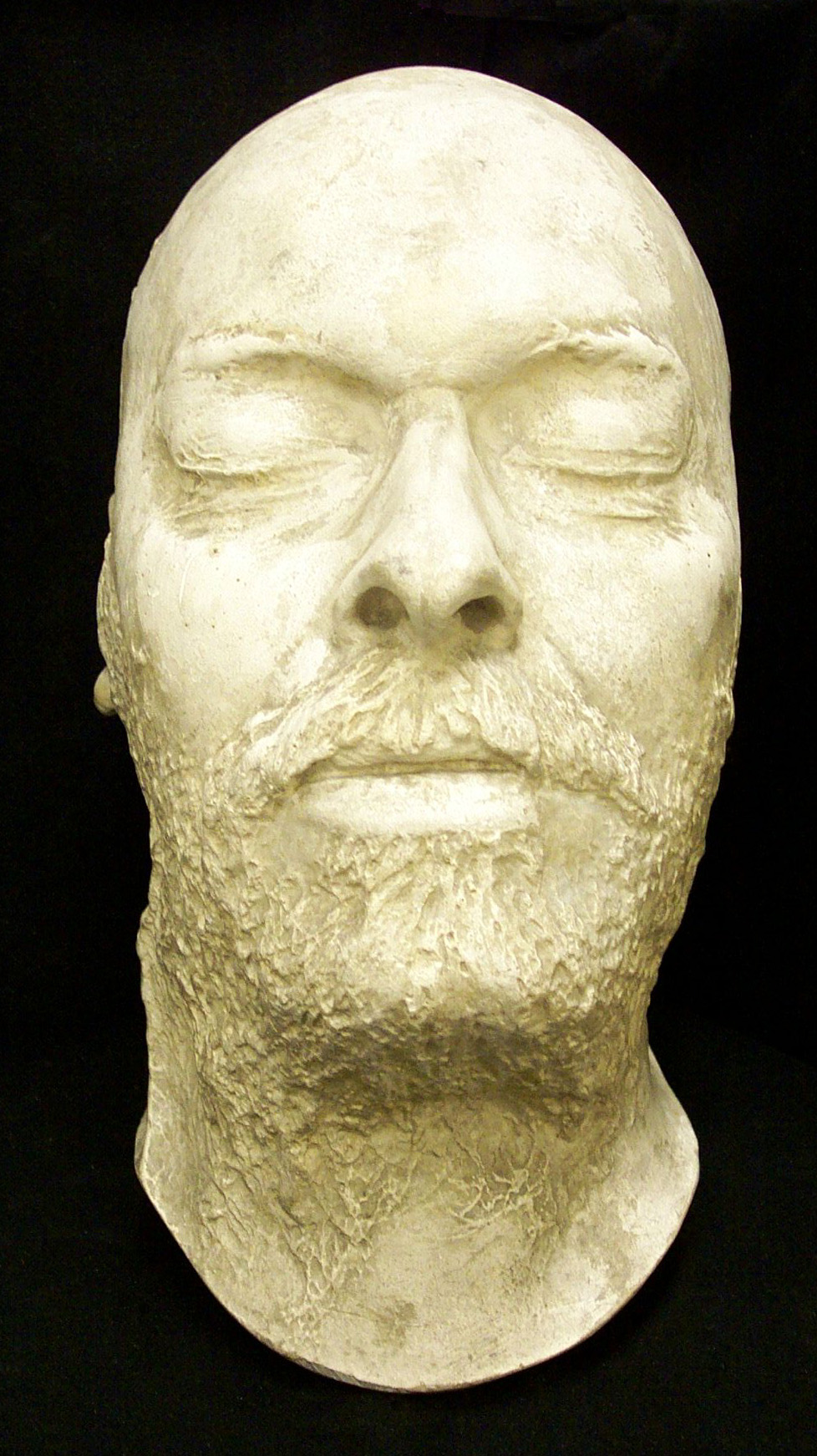

Rossetti’s death mask, 1882 (NPG)

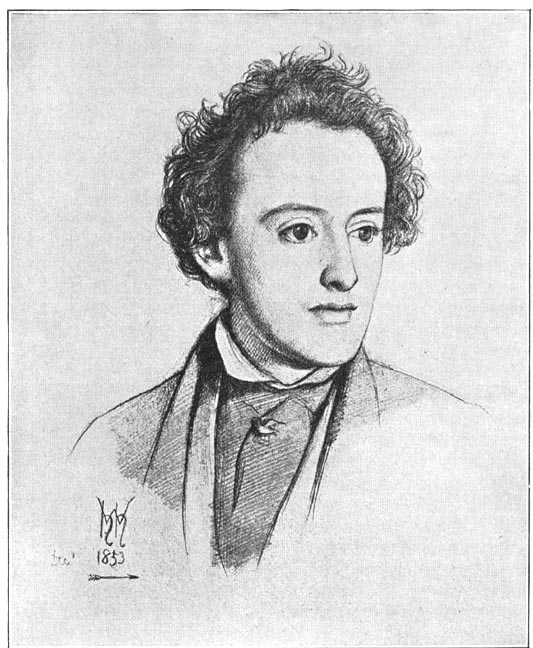

Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel, Rossetti, 1853

John Everett Millais (Biography)

Millais, Self-Portrait, Uffizi Gallery

Millais became the country gentleman and a member of the RA (and for six months its President before he died of what at first was thought to be influenza, but turned out to be throat cancer, he had been a constant pipe-smoker).

Hunt remembers is his autobiography the golden-haired Millais being manhandled to the front of the Royal Academy to receive a first prize when he was very young. If it can be said of anyone he was a born painter.

The fact that he joined the PRB shows the extent of his revolt against the establishment but he was made an ARA in 1853. However, in the end he probably changed the Academy more than it changed him and he changed it by making the PRB approach acceptable. Following the splitting apart of the original PRB all traces of his bohemian and rebel life were wiped out and he became respectable,later very rich and then a Baronet and President of the Royal Academy.

Facts from Victorian Art in Britain:

- As a young man he was extremely athletic. His party trick was to jump high into the air without any run (like Bill Gates).

- He was vain about his appearance. Nearly every photograph of him shows him in profile, as he felt that his profile was so exceptionally handsome.

- He was an outdoor man, every inch a Victorian hearty.

- He was addicted to field sports-hunting, shooting, and fishing.

- He was a sociable popular man.

- He was an indulgent father, particularly to his daughters.

- He spent his evenings in the Garrick Club, when in London.

- He did not visit sitters to paint their portraits, they came to his studio.

- In 1886 a large retrospective of his work was held at the Grosvenor Gallery.

- After his death Sir George Reid, President of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art said he was ‘one of the kindest, noblest, most beautiful and lovable man I ever knew or hope to know’.

Winfield, Millais as Dante 1860s

Hunt, John Everett Millais, 1853

The Uffizi Self-Portraits

The Uffizi has a gallery of the greats of art, such as Raphael. Both Hunt and Millais sent self-portraits to the Uffizi which were accepted. They also have self-portraits of Lord Leighton and Watts and other English artists,

The Victorians understood history and saw their place in history and thought of themselves as a chapter in history. So they naturally asked, who are the great figures of the Victorian Age?

Self-Historicizing. Compare the self-portraits of Hunt and Millais at the Uffizi.

Hunt wears an oriental shawl that probably belonged to his wife who had just died and an oriental blue-striped tunic. The embroidered scarf could be the one in his wife’s portrait. How did Hunt paint it as he is not looking towards us, did he use a photograph? Is it meant to be seen with his wife’s painting? Is he in a drawing room or his studio or heaven? Hunt was preoccupied with the idea that his wife was looking down at him from heaven.

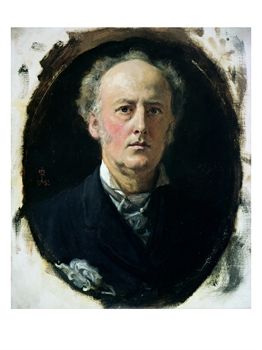

Millais, Self-Portrait (Uffizi).

Presents himself as the country gentleman. Is he emulating Rembrandt? The painting has a brown tonality, a quizzical gaze and strong chiaroscuro. Compare:

Rembrandt, Self-portrait, 1661 (aged 55)

‘Life Writings’

In Victorian England there was an explosion of interest in ‘life writings’ or

(auto)biographies as we would call them.

- John Guile Millais, The Life and Letters of John Everett Millais, President of the Royal Academy. 2 vols.

- William Holman Hunt, The Pre-Raphaelites and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, 2 Vols.

- William Michael Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 2 Vols.

- William Michael Rossetti, The P.R.B. Journal: William Michael Rossetti’s Diary of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood 1849-53, Ed. William E. Fredeman Oxford: Clarendon, 1975.

- F. M. Heuffer, Ford Madox Brown, A Record of His Life and Work

- M. S. Watts, George Frederick Watts, 3 Vols.

Biographies appear to provide a shortcut to interpretation and understanding. However, we must question them and the motivation of the writer. Many were written by the artist or someone close to them. Many were written by very old men who were making a point to the younger generation.

At this time there was also an explosion in journalism, penny papers, esoteric journals of all types, cartoons, obituaries and biographies.

Many appreciations were published in the early 20th century, such as Mrs. R. Barrington G. F. Watts, Reminiscences, 1905 and G. K. Chesterton’s G. F. Watts. These were often slim volumes bound with gold lettering expressing their personal views of the artist.

There were also many ‘in the studio’ publications presenting the artist as a personality in their studio (‘Hallo’ magazine style with photographs and word portraits).

- Henry Treffry Dunn, Rossetti in his Studio, 1882

- Fuller, Millais in his Studio, 1886

- Ballantyre, Hunt in his Studio, 1865

Each decorated their studio according to their personality. Rossetti had peacock walls, porcelain, an aesthetic interior. Hunt is in his Jerusalem studio wearing eastern clothes. Millais is shown just before he became PRA looking like an English gentleman in his well upholstered studio.

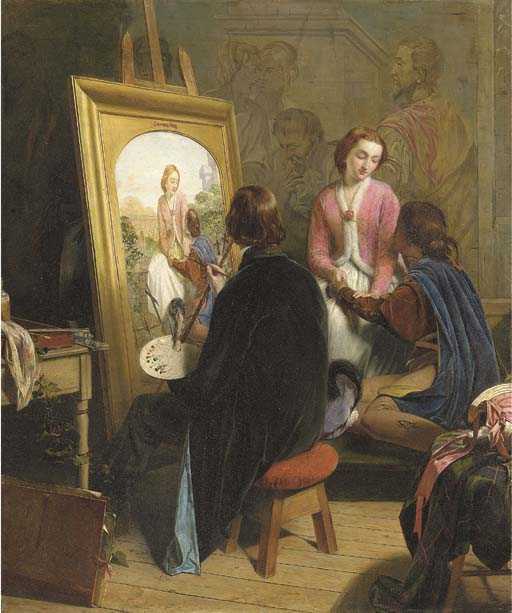

O’Neil presents a different view.

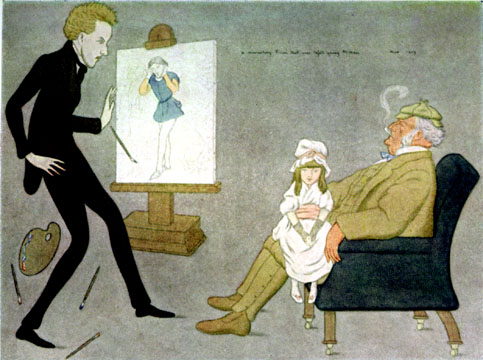

O’Neil, The Pre-Raphaelite, 1857

O’Neil was a member of the Clique who were against the PRB style which they found painstaking and didactic. In the 20th century Beerbohm satirised the PRB with a book and a number of engravings.

Beerbohm, A Momentary Vision once Befell Young Millais, 1922

There is another of Hunt nagging Brown and another of Rossetti talking to Christina about fabrics.

Julia Margaret Cameron tried to take photographs of all the famous people

(mostly men) of the period. Tennyson, 1865; Carlyle 1867; Longfellow, 1868;

Palgrave, 1868; Rossetti, 1865 (bohemian); Hunt, 1864 (in oriental garb,

brightly lit and priest like); G. F. Watts (shown as he was known as the English Michelangelo).

Watts, 1865, Whisper of the Muse.

Watts wanted to paint all the great people of the period and they were donated to the NPG, Cameron, Rossetti, Millais but not Hunt.

Thomas Carlyle. On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History.

In all epochs of the world’s history, we shall find the Great Man to have been the indispensable saviour of his epoch;–the lightening, without which the fuel would never have burnt. The History of the world, I said already,

was the biography of Great Men.

How does one grant the status of a hero to a contemporary figure as it is normally associated with figures of the past?

Carlyle said,

The essence of the Scandinavian, as indeed of all Pagan Mythologies, we found to be recognition of the divineness of Nature, sincere communication of man with the mysterious invisible Powers visibly seen at work in the world round him. This, I should say, is more sincerely done in the Scandinavian than in any Mythology I know.

Did Carlyle influence the PRB more than Ruskin. His writing sometimes sounds like a manifesto of their general principles but it is not related to painting as is the work of Ruskin. Carlyle was very well known and set the tone of the age.

Carlyle based his philosophy on four major tenets:

- The universe is fundamentally not an inert automatism, but the expression or indeed incarnation of a cosmic spiritual life;

- Every single thing in the universe manifests this life or at least could do so;

- Between the things that do and those that do not there is no intermediate position, but a gap that is infinite;

- The principle of cosmic life is progressively eliminating from the universe everything alien to it; and man’s duty is to further this process, even at the cost of his own happiness.

The sage:

- Points to an contemporary phenomena

- Interprets it

- Predicts a final disaster if they continue their evil course

- Offers a hopeful vision of bliss and prosperity if they improve.

The PRB gave the Writer of the Book of Job four stars. Job is remembered as an insightful sage and prophet but was abject and ordinary. Christ is the ultimate ordinary hero. You can imagine you are a hero after reading Carlyle even if you are living in a Victorian garret.

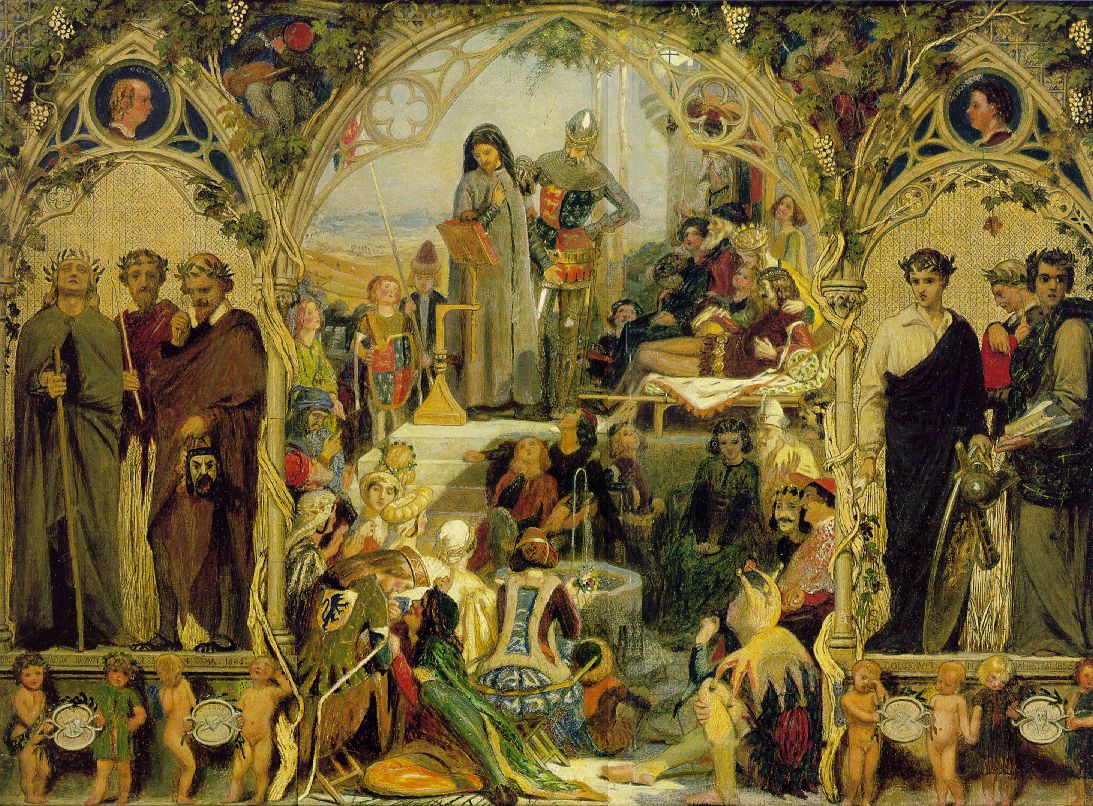

Ford Madox Brown, The Seeds and Fruit of English Poetry, 1845-51

Entered in the competition for the Houses of Parliament frescoes. Chaucer is shown at the moment he is changing the course of English history.

Brown, The Seeds and Fruit of English Poetry

Brown’s Work can be seen in a different light as images of great men. Carylye (who is in the picture) said great men could ne ordinary people. Carl Marx was also writing at this time.

Based on Woolner leaving England to get work, he came back two years later and caused a great deal of trouble.

Millais, Boyhood of Raleigh, 1870

Is a key picture to think about regarding heroes and ordinary people. Hunt also painted great men in The Light of the World, 1853 (Christ) but he also painted the opposite Claudio and Isabella, The Hireling Shepherd, 1852, The Awakening Conscience, 1853, Rienzi, 1850.

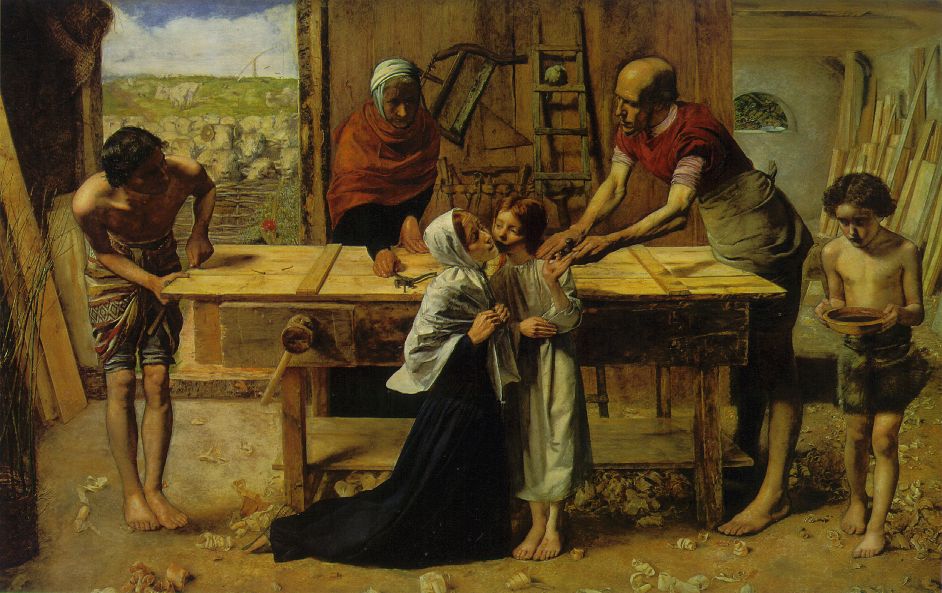

Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents, 1849

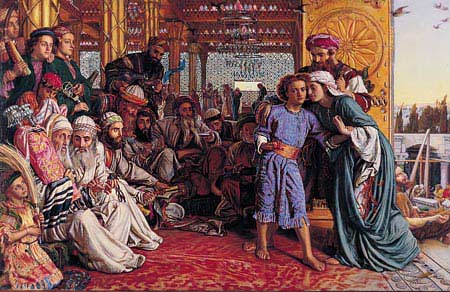

Hunt, The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, 1862

In his autobiography Hunt describes the first time he went home with Millais and his parents greeted him as Christ’s parents are greeting him in the painting. The priests on the left could be seen as the Academicians opposing Millais (at the time).

(These are notes of a course given at Birkbeck College by Carol Jacobi in 2006/2007)