Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Found, started 1854 and still unfinished at his death in 1882.

The fallen woman was a popular subject in Victorian painting. It is possible that Burne Jones and Rossetti’s assistant worked on this painting after his death. Rossetti had written to Hunt describing the story behind this painting and words from Jeremiah are inscribed on the painting.

We also have a study drawing in which the woman is more tawdry and the drawing has railings on top of the wall in front of a graveyard. The bridge is Blackfriars Bridge which was outside his house. He went to Ford Madox Brown’s house to paint the calf. Brown said he painted the picture hair by hair and it received a negative reaction from Ruskin.

The driver is more dominant and threatening in the painting and more sympathetic in the drawing. In the painting he changed the face to that of Fanny Cornforth and it is very similar to a study drawing of her. He never changed the painting even though he worked on it for years. Her anguished expression is associated with the words, ‘Leave me, I do not know you, go away.’ She looks away and the drover is staring out of the picture rather than at her.

There is a suggestion that it is a sacrificial lamb and another suggestion that the lamb represents his relationship with Lizzie Siddal and she was tied down by him like the lamb. It has also been seen as a metaphor for life where high ideals when young end up in the gutter. Linda Nochlin has argued that Rossetti saw himself as a prostitute pandering to the requirements of his patrons by producing ‘pot boilers’ for money.

A lot of detail has been removed between the drawing and the painting. The bollard has been changed to a more phallic cannon. The drover has tight boots and stitching and seems to be demonstrate a certain instability. The dawning light suggests hope but their conflicting expressions suggest little hope. Another reading, by Linda Nochlin, suggests it represents his failure as an artist.

It is an unsettling and unsettled image with unresolved ambiguities. The fallen woman and the redeeming man theme can be compared with Hunt’s Awakening Conscience. The painting is proto-Freudian, e.g. the phallic canon but at the time although sexual symbolism was being explored it was being done naively. Thomas Fairbairn, Hunt’s patron and owner of Awakening Conscience asked Hunt to paint over Annie Miller’s pained expression and we do not know what it originally looked like but the face of Fanny Cornforth in Found may be an indication.

Both paintings illustrate the theme of the ‘unsettled subject’ as it is very difficult to pin down the exact role of each subject even though the role appears clear. For example, critics at the time thought they were brother and sister in Awakening Conscience.

Both paintings illustrate the urban and the woman becomes a cipher, that is a way of understanding, the urban. Prostitution is a way of understanding the role of the working woman. It is now thought, although not known, that woman rural workers were readily available for sex for a payment but in the urban environment the nature of the transaction changed from casual to a specific financial transaction that was part of the economic circumstances of living and working in the city. There was a lot of anxiety about urban prostitution and the working woman because it created new values and because it was a visible part of the urban crowd.

It was part of the bigger issue of seeing and being seen in the city to do with legibility and decoding. The city visually overloads the viewer, people stream by and must be codified and understood if they are to be dealt with and confronted or even coped with. Certain categories of person, such as the prostitute, suggested the fall of civilisation as if everything could be traded nothing was sacrosanct.

Everything was displayed for sale. Plate glass and more extensive gas lighting was introduced and there were large window displays where people could stroll and look. And they could look at each other and if everyone was salaried everyone could be bought and this made everyone a commodity to be traded. There was a plethora of over visibility and a mixing of classes and ages in a way that had never occurred before. The men of independent means who were not salaried were above the trading system and could parade around the throng observing what could be bought. In France, Baudelaire described the flaneur as part of the city and modern life.

Rossetti had a complex relationship with women. Fanny Cornforth did quite well out of prostitution and bought a pub that Rossetti often visited in his old age for a chat. Annie Miller (Eliza Doolittle to Hunt’s Professor Henry Higgins) also did well out the profession of prostitution and was for years the mistress of the seventh Viscount Ranelagh and eventually married his cousin.

Why did Rossetti never finish Found? Was it because he had never resolved the issue of fallen women. His life had a Freudian ‘uncanny’ episode when his lover and then wife Elizabeth Siddal died of a laudanum overdose reminiscent of his hero Dante’s relationship with Beatrice. Does the painting have less value if it merely reflects his personal view and personal relationships, or is this true of all painting?

If we read Rossetti’s poetry we get a better view of his view of women. Did he abuse them and turn them into his fantasy? Does he attempt to give women a psychological dimension? The answer is probably yes but it is not clear he was successful. He rejected Ruskin’s view that all painting should have a moral purpose.

Did the women associated with the PRB need rehabilitating? Annie Miller seems to

have enjoyed her career and was successful. So were they the victims they are

presented as? When Lady Emma Hamilton (Amy Lyon), Lord Nelson’s mistress, danced naked on the table for his friends was she being abused or was she using and exploiting the situation and her beauty.

Perhaps Found was started as a moral view of shame but was never finished as he could never resolve whether shame was appropriate. He spent more time on the brick wall, a metaphor for the urban experience, ‘hair by hair, brick by brick’, a demonstration of the endless minutiae of existence combined with the repetitive nature of commercial production.

Nature and the Natural World

Alfred Lord Tennyson, In Memoriam

Extract from his poem:

Man, her last work, who seem’d so fair,

Such splendid purpose in his eyes,

Who roll’d the psalm to wintry skies,

Who built him fanes of fruitless prayer,Who trusted God was love indeed

And love Creation’s final law —

Tho’ Nature, red in tooth and claw

With ravine, shriek’d against his creed —

Who loved, who suffer’d countless ills,

Who battled for the True, the Just,

Be blown about the desert dust,

Or seal’d within the iron hills?

Ford Madox Brown, An English Autumn Afternoon, 1853, 1855.

Millais’s Ophelia is about his particular experience of nature. Ophelia gives rise to feelings of solitude, becoming absorbed by nature, becoming one with nature, a claustrophobic feeling and a stillness. It is a flowing picture with no horizon (one of the first landscapes with no horizon), no boundaries, diffuse edges. We are very close to Ophelia and above her like lovers in a bed of nature.

Millais spent 11 hours a day painting the leaves one by one on the banks of the Hogsmill River in Esher.

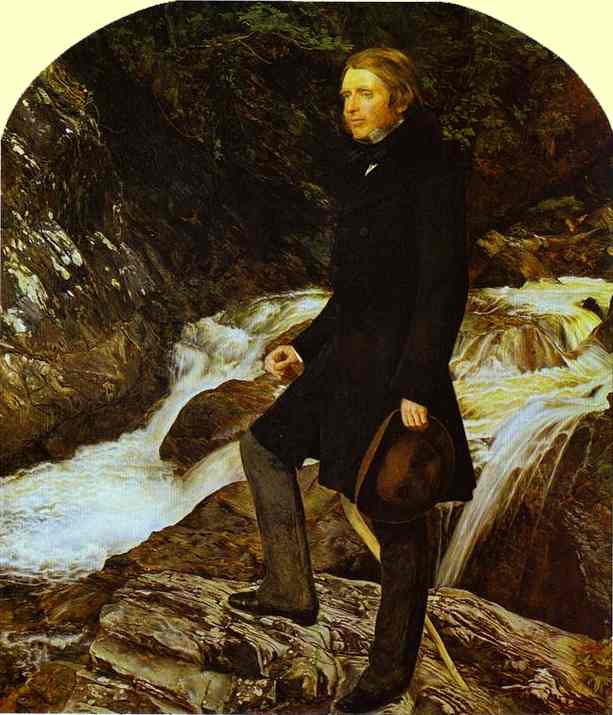

On the other hand this view of nature gives rise to thoughts of motion, movement, tight edges, someone who is master of his own ideas, in control. He is dressed for the city and looks awkward, partly because Millais painted him later in the studio, but partly perhaps intentionally. The rocks demonstrate his knowledge of geology, the thinker in dreamy melancholic pose. A reminder of Monarch of the Glen. A vertical action picture as opposed to a horizontal, sleeping, dreaming picture.

Next compare each of the following with each of the above three paintings.

A painting that presents itself realistically and painted on the spot under dangerous conditions yet at the same time it is a symbol of Christ. It is strongly physical and strongly religious.

A mood, no figures so it forces you to feel yourself in the scene. There is no distraction but a slight feeling of unease perhaps related to the startled (?) birds. It is a cold autumnal light, a feeling of isolation, a softness of textures, no firm forms, we are absorbed. A symbolist painting that sets up a set of emotions in the viewer. There is a rustling of grass (synaesthesia).

We see the atmosphere, the rain has just fallen, the sun has come out. The girl has flushed cheeks from walking in the open, it is still a hot day. There is a physical link with nature, she fingers the blades of grass. It is halfway between Ophelia and Ruskin. Her perception is not visual and as Kate Flint writes it illustrates the Victorian notion of the heightened sensibilities and inner sight of the blind.

Hunt, The Thames at Chelsea Evening, 1853

[This page is based on notes taken during a lecture given by Carol Jacobi at Birkbeck College, University of London. Any errors are my own.]