Ford Madox Brown’s Work tells us a great deal of the evolving streets of Victorian London. It took 11 years to finish, from 1852 to 1863 and Brown was supported during most of this period by a Leeds’ stockbroker called Plint. He was deeply religious and the painting reflects social religious beliefs. Unfortunately, he died before the painting was finished. The corners of the painting which had a rounded top like an altarpiece, had religious texts and the sunlit scene can itself be seen as the light of divine grace falling on work. At the top (a social hierarchy) and two people on horses that Brown described in the handout accompanying the one-man show, as gentry and he is meant to be an MP whose income if £15,000 a year. One of Brown’s heroes was Hogarth and the aristocracy are shown in the shadows as they are an irrelevance to work.

The workers in the centre are digging a trench for a sewer or a new water main (which is debated by art historians and the most likely is a water main). Clean water was becoming recognised as important for preventing cholera which had killed 10,675 in 1853 and Dr. John Snow’s investigation of the Broad Street Pump in 1854 is now regarded as one of the greatest medical analyses of all time and recently Snow was voted the greatest doctor of all time.

The lady in the blue dress is doing no work and the lady behind her is distributing tracts on temperance although one worker is shown drinking from a sparkling tankard at the same level. Brown was not a believer in female emancipation.

The strange man on the left with a hat collects and sell single specimen plants that he collects from the country and sells to London botanists. He has no recognised trade or profession and did not have regular employment so was not respected by Brown.

The group of probably Irish immigrants on the right under the railing would be agricultural workers and the blade of his scythe wrapped in rope can be seen.

Brown went round London photographing people to use in the painting. others in the painting were friends as he did not like to use professional models. The girl at the front wearing the black arm band has taken on the role of mother after her mother has died and it would have been recognised that she would be likely to have taken up prostitution to keep herself and her baby sibling fed.

In the road a group have boards advertising to vote for an MP (perhaps the

one on the horse). On the far right a policeman is stopping a woman from selling

oranges which are spilling on the ground (we don’t know why). Also on the right

are the ‘brain workers’ Thomas Carlyle and Frederick Maurice.

The site is the Mount, Heath Street (seen on the right) in Hampstead. The site is still recognisable.

The one-man show for the painting was in 1865 but was only a qualified success even though it was heavily advertised.

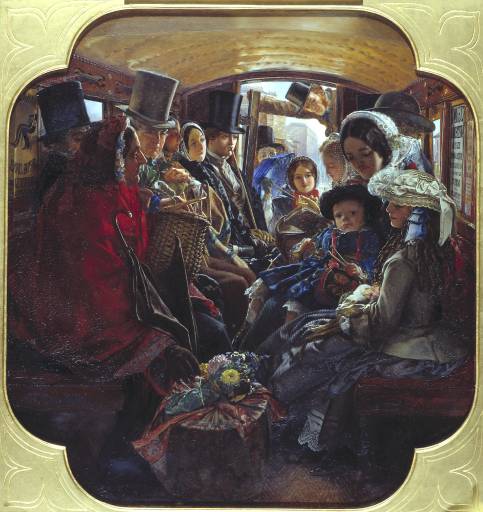

William Maw Egley, Omnibus Life in London, 1859

Everyone is mixed together, a new type of social mixing. It has a claustrophobic

feel, the figures are close to the picture frame and everyone is displaced.

Egley was a background painter for Frith (The Railway Station, Ramsgate Sands).

The painting is a study in physiognomy a Victorian pseudo-science that was very popular. Note the woman on the left is like the woman in the Railway Station so he probably used the same model.

The Pre-Raphaelite technique was ideal for studies of physiognomy as everything

is shown very clearly. Egley was moralising in this painting which would have

been clearly read by Victorian viewers. The man and woman on the left are

country folk with their round faces and country produce. The chap on the left at

the back is a flaneur type, 10 years before flaneur were painted in Paris.

Opposite is the young woman he is staring at. In fact everyone of the left is

staring at everyone on the right although for different reasons. The blond young

woman is pretending to read a book but must be conscious of the man’s gaze and

is coquettishly (?) playing with her gloves. So is it showing the empowerment of

woman, they are able to travel on their own and flirt with the man.

In 1858 women petitioned to join the Royal Academy although the next woman to

become an RA was Laura Knight in 1936. The Bronte’s were writing under their own name and Ada Byron, who had been bled to death by her physicians in 1852, was a recognised scientist. According to Egley the girl at the front right was 12 years old.

Egley had a fascination for women’s feet and shoes and they are frequently

discussed in his diary. His pictures often show a foot and sometimes a small

piece of petticoat sticking out from under a dress and when you look other

Victorian paintings do the same. For example, look for dainty feet in Work.

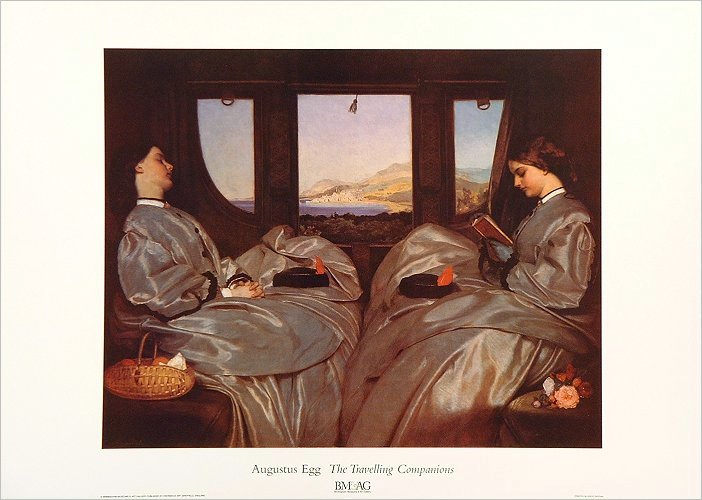

Augustus Egg, Travelling Companions, 1862

Initially the women look similar but on closer examination the woman on the

right is the ‘good’ woman and the woman on the left the ‘bad’ woman. The woman

on the right has hands covered in gloves, a book, flowers on her hat and

mountains behind her. The woman on the left, is sleeping in public, has her

dress undone (one button), has naked hands, is flashing her cuffs, has flushed

cheeks, a basket with oranges and the open sea behind her.

The Legible and Illegible City

The paintings being considered are about the subject and the subject in the

city, not about the city itself. The body of the woman becomes a cipher that can

be used to read the spaces of the city. Victorian painters were rarely

completely stereotyped in their representation of women and multiple

interpretations are possible including a positive and active role for women. We

need to read the signs correctly and not assume they are simply showing us the

good and the bad, each figure is often ambiguous. An unchaperoned woman was a

‘bad’ thing as it suggests a fallen woman but it is also a ‘good’ thing as it

suggests female emancipation. There were many examples in cheap literature of a

couple of women, one blond and the other brunette where the blond woman was

meant to be ‘good’ and innocent and the brunette ‘bad’. Courbet’s Sleepers also

plays with this tradition.

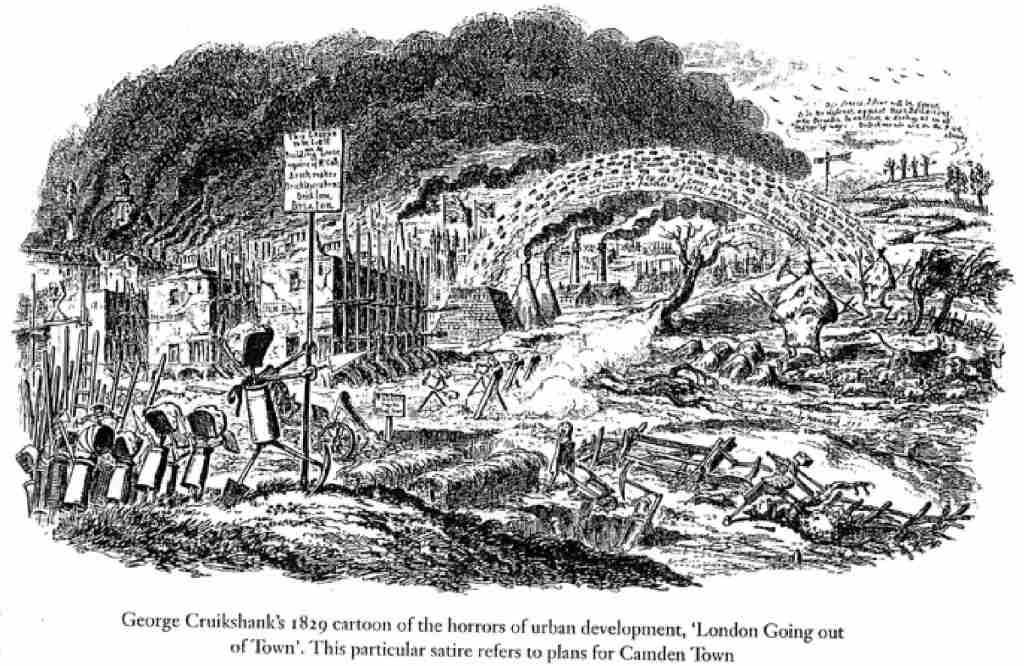

London grew substantially in the 19th century into a ‘super’ city, the largest

in Europe.

Cruikshank’s London, Going Out of Town, 1829 shows the mixed feelings associated

with the growth of the city and the opposition of rural/urban, country/city,

nature/town is discussed in a lot of the literature.

Many city scenes can be viewed as glorification of fragmentation and the same is

true today. Do we glorify our multi-cultural society or do we worry about

dissention and fragmentation, we can look at it either way.

Linda Nead’s Victorian Babylon is a key text, see

the

review. Her book divides into:

- Mapping, new ways of looking, John Henry Banks, A Balloon View of London, 1851. Maps of the sewer system, Ordnance Survey. All caused the Victorians to view the world from multiple perspectives.

- ‘Health’, the city viewed through the metaphor of the body.

- Cholera

- Gustave Dore, the dark city and the light city. Missionaries went to work in the dark city as they went to work in ‘darkest’ Africa. See A Couple and Two Children, 1871, Wentworth Street, Whitechapel.

- Water brings health to London, note the sparkle of light on the tankard in Work. Brown includes the poor in the picture alongside the rich. The dark and the light are merging.

- Street etiquette, ‘a complex system of looking and aversion to sight.’ A complex protocol. A gaze analysis of Brown’s and Edgley’s work would be interesting.

Spaces in a city change depending on the time of day, e.g. Regent Street

at 2 o’clock, Twice Around the Clock: Or the Hours of the Day & Night in London,

1859, (see the text) was when the swells (flaneurs) came out.

Cremorne Gardens (also see Wikipedia) was a popular entertainment centre. Fireworks at dusk was a signal for the beginning of the evening and was painted by Whistler.

Types and Polarities

People (mostly women) can be categorized as good and bad (as we did above), respectable and unrespectable and individuals can be read and the artists gave signals about the type being indicated.

Compare the woman in Awakening Conscience and

Hunt, The Children’s Holiday, 1864

The images and symbols are reversed. Both paintings were owned by the same person. The woman in the second was his wife. The model for the first was Annie Miller.

Prostitution was regarded as a major problem as we regard hooligans, a breakdown of society. Rossetti, Found, 1853, a complex image because of the calf from the country signifying sacrifice.

Culliford, ‘I am not a social evil…I am waiting for a bus’. Note the show peeking from the dress.

Phiz, Little Nell, David Copperfield, 1849, little Nell had gone to the bad and become a prostitute. There is a link from prostitution to the river Thames and disease, prostitution as a moral sewer and the idea of the drowned prostitute is very strong in literature although less so in life.

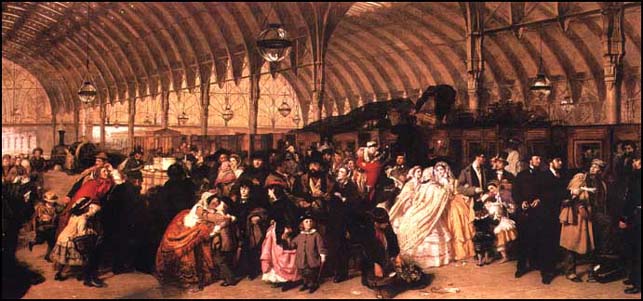

Frith, Paddington Station, 1862.

Physiognomy enabled Victorians to read the picture as easily as we can tell if

someone is dangerous on the tube. In the 19th century there were many books on

physiognomy and etiquette to help with the interpretation.

The crowd is an important theme. It can never be made legible but Frith made the

figures identifiable and this enabled the Victorians to read and so understand

and relate to a crowd. A crowd in a city is a blur of people but Frith’s crowd

has little narratives that can be decoded and this makes them legible.

Frith, The Times of the Day 2: Noon.

The flaneur – mobile, urban, insouciant, male (dedoublement, a word Baudelaire

uses to mean emotionally alert and watching yourself respond, so observing and

observing yourself observing), observes the etiquette, reads the nuances, the

too tight shoe.

1. ‘The line drawn increasingly sharply between the public and private was also

one which confined women to the private, while men retained the freedom to move

in the crowd or to frequent cafes and pubs.’ Wolff, ‘The Invisible Flaneuse:

Women and the Literature of Modernity. Wolff could not find the flaneuse.

2. Griselda Pollock responds to Wolff’s suggestion in her essay ‘Modernity and

the Spaces of Femininity.’ Pollock said we need to look for women in the private

spaces, such as the drawing room.

3. ‘girls from respectable families walk unaccompanied in London and that this

can provide sought-after opportunities for sexualized encounters with strangers’

Nead said no, the women were out there in public.

Richardson, Holywell Street, 1850s, watercolour. See Victorian Babylon.

Middle-class women not only visited the street but they looked in the windows at

the pornography.

Emily Mary Osborn, Nameless and Friendless, 1857.

The anonymous city is outside. A network of gazes. It sets up a lot of questions and reminds us that a painting is a dialectical thing.

(These are notes of a course given at Birkbeck College by Carol Jacobi in 2006/2007)