Awakening Conscience, Holman Hunt, 1853

Hunt’s Awakening Conscience was exhibited at the RA in 1854 and not everyone understood its significance. At the very centre of the picture are the lady’s crossed hands which reveal a ring on every finger save for the third digit, left hand — the wedding finger. The New Monthly Magazine thought it was a brother and sister and it looked as if ‘she had been asked to sing at the wrong moment’. However, most critics got the point — she is unmarried and in a state of semi-undress. The Athenaeum described it as ‘drawn from a very dark and repulsive side of modern domestic life’. With a great though mistaken depth and Frederick Stephens picked up on the ‘maison damnees’ setting. Ruskin weighed in with his own moral/didactic interpretation with a letter to The Times detailing its ‘terrible luster’ and ‘fatal newness’ as a defence of the picture and the PRB in general.

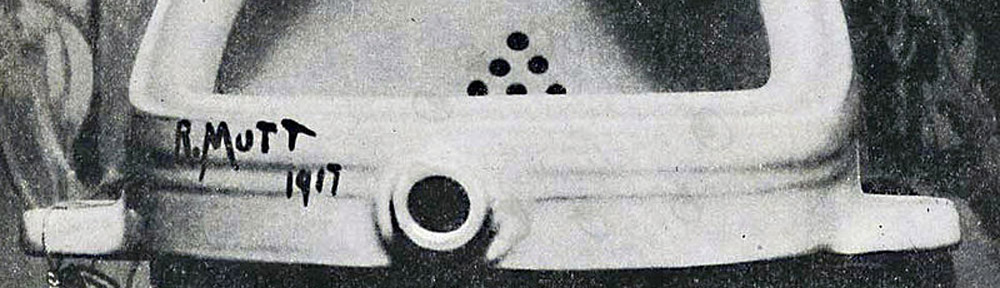

As Ruskin pointed out every feature — the title of the book, cat capturing bird, Tennyson’s ‘Tears, Idle Tears’ (rolled up bottom foreground left), soiled and cast off glove by her feet, tangled/unraveling threads [applicable to Lady of Shalott?], the music on the piano, sleeping cupid in the wall paper, clock on the piano (Chastity binding Cupid — under glass), the fowls of the air on the wallpaper — he got the picture above the piano wrong. It is actually Frank Stone’s Crossed Purposes [1] (with all that the title implies). What we are looking at is nature reversed. Socially (mistress vs. wife) and literally (the garden seen through its reflection in the mirror). The white roses (for purity) are outside, beyond her reach.

The frame was decorated with marigolds (for sorrow) and bells (warning).

This is not Hunt’s original title. The model was Annie Miller (though the face was subsequently repainted by Hunt at the request of the purchaser — Fairburn). Conceived whilst working on The Light of the World he worked on Awakening during the day and Light at night.

Holman Hunt, The Light of the World

Compare the two. Ironic that he was painting such a moral tale using his own mistress as the model. A warning to her? He was trying to educate her this is what happens if you don’t listen? Show her off?

In Light there are two sources of light — the lamp represents conscience and the halo, salvation. In Conscience there is the direct daylight which falls short of the mistress onto the corner of the piano. Light of conscience missing her? Then there is the reflected daylight which falls on her hair — a slight halo? — indirect salvation? Does the arched top reflect the imprisoned chastity binding cupid under the glass dome on top of the piano?

If we were in the room, surely we would be reflected in the mirror.There is still more research to be done on the spatial ambiguities.

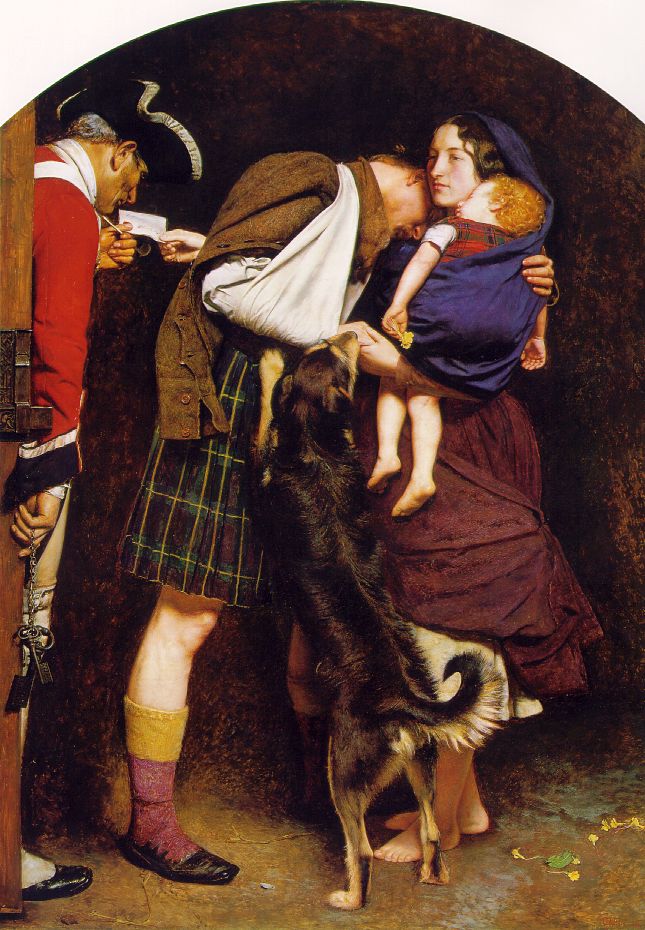

The Order of Release, Millais, 1852-3

This shows the (fictional) release of Scottish soldier following the Jacobite Rebellion of 1746 under Bonnie Prince Charlie. Effie Ruskin was the model. One modern interpretation is that the wife has given sexual favours to secure her husband’s release.This is referenced by the dog (a symbol of loyalty) in the closely bound family group.The primroses which the child holds (and drops to the ground) represent loyalty too — particularly in respect of children.

It can be said to be a picture of three soldiers — English, Scottish and the woman who has had to fight her own battles. She has a strong, dominant role in this picture — the only one whose face we can see.She is shown as good, hard-working, honest — not a floozy (see bare feet). We infer from the blue shawl, worn Madonna like — particularly with a child in her arms — references to the Virgin, not Mary Magdalene.

Sketch,1852

Note the the sketching capabilities of Millais — soldier looks younger, Effie prettier but not the composition. The child is less active in the finished work and bound to the mother alone rather than linking the parents as in the sketch.Thus in the finished work the wife is more isolated, stronger and we study her psychology rather than see it as a simple, joyful reunion.

Compare with:

Holman Hunt, Claudio and Isabella, 1850

George Elgar Hicks, Woman’s Mission: Companion of Manhood, 1863[2]

These can also be seen as images of a woman supporting her man but in different ways.

Elastic Sexualities/’At the Feast’/Alternative Lifestyles all encompass a similar theme

concerned about gender in the nineteenth century. The sexuality of the individual, social practices/norms, actual lives/biographies.Thus Awakening Conscience can be seen as a narrative, a comment on general society, a reflection of Annie Miller’s life.

One thing to beware — generalities across 19th century.Just as culturally the 1930s different dramatically from the 1960s which differed markedly from the 1980s.So too in 19th century.Therefore the pictures we are going to talk about today are deliberately specific to the early 1850s.

Read Ruskin’s Sesame & Lilies[3] text — a masterclass in misogyny.

Work of two halves: Of Kings’ Treasuries, in which Ruskin critiques Victorian manhood, and Of Queens’ Gardens, in which he counsels women to take their places as the

moral guides of men and urges the parents of girls to educate them to this end.

Feminist critics of the 1960s and 1970s regarded Of Queens’ Gardens as

an exemplary expression of repressive Victorian ideas about femininity, and

they paired it with John Stuart Mills’s more progressive Subjection of Women

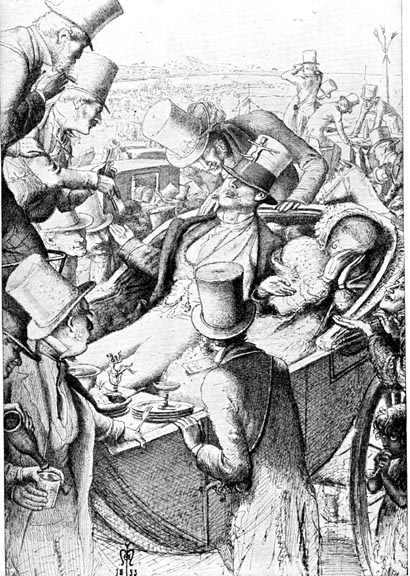

Drawing for The Deluge by Sir John Everett Millais c. 1850

Society is dangerous.Lover/individual is at odds with society.This is a recurring theme in Millais’s work at this time.

The deluge (another feast — think society) where no-one notices the flood rising save for

the reversed Christ-like figure and the woman trying to attract the wedding revelers attention.Note the spikiness of the composition.The feasters are society, feasting is consumption.

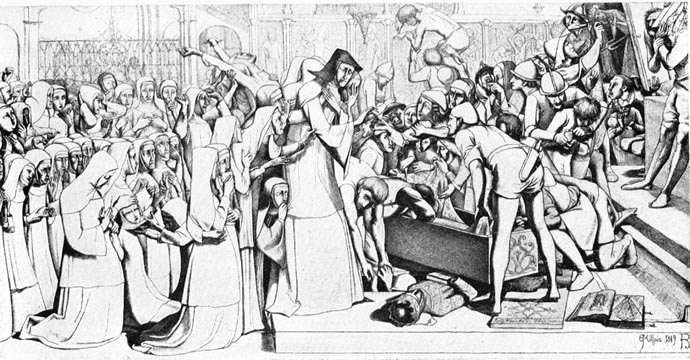

The Disentombment of Queen Matilda by Sir John Everett Millais, 1849

The Return of the Dove to the Arc, Millais, 1851

Here again, in The Disentombment is a crowd scene, violent, unsettling.Compare to Return of the Dove which is a pioneering example of the simple composition favoured

by Millais.The empty space surrounding the simple singular (or in this case double) image makes us focus on what is going on.This is safety after the flood.Private, contained.But.. there was a suggestion that it was simply that Millais didn’t have time to fill in intended background people!

Millais, A Huguenot, on St. Bartholomew’s Day refusing to shield himself from

danger by wearing a Roman Catholic badge, 1851-3

Ophelia: The utterly private moment of her death, away from the bloody, murderous activities at the castle, the violence of the political machinations involving a wedding.

Huguenot: The narrative is a lady endeavoring to bind a scarf round the arm of her Huguenot lover, which was the agreed distinguishing mark for Roman Catholics at the time of the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew. Private moments of love surrounded/backgrounded by violence.Carol’s oft-mentioned desire to examine the significance of the painstakingly painted brick wall[4].

Millais, My Beautiful Lady, aka Lovers by a Rosebush, 1845

Millais. The Woodman’s Daughter. 1851

The ruining of a young poor girl by aristocratic boy. Endictment of society’s double standards, marriage as a class weapon [5].

Millais, L’Enfant du Regiment, 1854-5, Carol:The innocence and purity of love likened to innocence of childhood.

Yale:Millais derived his subject from Donizetti’s opera “La Fille du Régiment.” The heroine of the opera is Marie, offspring of a secret liaison between an aristocratic Englishwoman and a French army officer. After her father’s death in battle, Marie is adopted by his regiment. The action of the opera takes place in 1805, during the Napoleonic Wars, and she is no longer a child but a young woman. The scene in the painting, a pathetic incident from her earlier life, is the artist’s own invention: during fighting in a church she has been wounded and lies sleeping on a knight’s tomb.

Millais, The Race Meeting, 1855

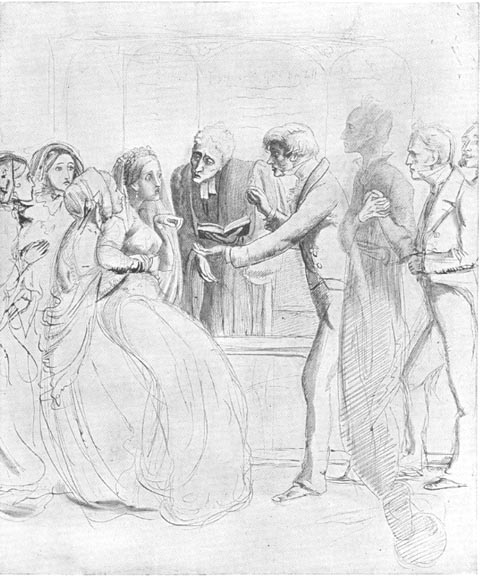

Millais, The Ghost, 1853

The Race meeting is one of a series of drawings dealing with marriage. Here an unfortunate woman has married a wastrel who is squandering the money at the

races.

The subject of this drawing is the marriage ceremony attended by a ghost — former lover or husband — clutching his broken heart as he rises up behind her bridegroom.

V&A: However, it may allude to the marriage of Effie Gray (who once owned the drawing) to John Ruskin in 1848.At the date that the drawing was made, she and Millais were in

love. Her marriage was annulled in 1854 and they married the following year. The figure on the right could be Ruskin’s father, a dominating man who tried to run his son’s life, and the ghost is Ruskin’s grandfather, who committed suicide [in the Effie/Ruskin marriage house?]. It is an image of great intensity, remarkable for its convincing rendition of the natural and supernatural. The drawing is, however, unfinished. Perhaps the subject became too painful for Millais to pursue.

See Millais’ Drawings of 1853, by Joan Evans, The Burlington Magazine, Vol.92, No.568, Jul.1950, pp.198,199,201 (JSTOR)

Study for Huguenot, 1851

Martin Chuzzlewit.Born in Manchester at the turn of the nineteenth century, Frank Stone left a secure position in his family’s textile firm in 1824 to become a free-lance artist. Even though he had no formal training, his portraits had sufficient sentimental appeal to attract the attention and friendship of such established London artists as Maclise, Cattermole, Thackeray, Frith, Egg, Millais, and Mulready. In the mid-19th century Frank Stone also served as the principal fine arts reviewer for the influential literary journal Athenaeum. As such, he published several unfavorable reviews of the works of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and was an early and vocal opponent of the Pre-Raphaelite style.

[2] Tate Britain:This work was the central section of a triptych called Woman’s Mission exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1863. The two other parts, Guide of Childhood and Comfort of Old Age, are now lost. These showed the woman tending her son and ministering to her father in old age.The woman comforting her husband, who has just

received bad news. The Times newspaper described the works as representing woman in three phases of her duties as ministering angel.

[3] John Ruskin’s Sesame and Lilies, first published in 1865, stands as a classic nineteenth-century statement onthe natures and duties of men and women.Sesame

and Lilies by John Ruskin; Edited and with an Introduction by Deborah Epstein Nord; With

essays by Elizabeth Helsinger, Seth Koven, and Jan Marsh.

[5] Seduction and unrequited love.Difference in clothing, the boy also appears at odds with the forest – while Maud and her father almost blend into the woods, the squire’s son stands out and is out of place. Is the boy, clad in fiery red and visually at odds with the natural surroundings, at fault? Is the girl at fault for not exhibiting proper discretion, or for being too naive? Or, perhaps, is the father at fault? He is, after all, working with his back turned to

his daughter, not realizing what is taking place. Are there any visual cues that indicate a culprit?Henry Hodgkinson bought this painting, but he asked Millais to first repaint the girl’s head. Millais repainted her head, hands, and feet. As a result from this reworking, a dark aura appeared around those areas of the girl. Even though this discoloration was unintentional, does it somehow add to the painting?

(These are notes of a course given at Birkbeck College by Carol Jacobi in 2006/2007. Many thanks to S. Sharp for supplying her notes for this lecture.)