Materials and Techniques (Printmaking) 2-2-2004

Printmaking lecture by Robert Maniura.

By Michelangelo’s time drawings were collected but previously they were just sketches.

The appeal of drawings is that they are made by the artist rather than by a studio. Drawings are also very immediate. But prints are mass produced and the

artist may not have touched them at all. Printed reproductions, for example, in books are on paper. Also books are mass produced. Illustrating books is a

very early technique. Also reproductions are often reproducing another artwork.

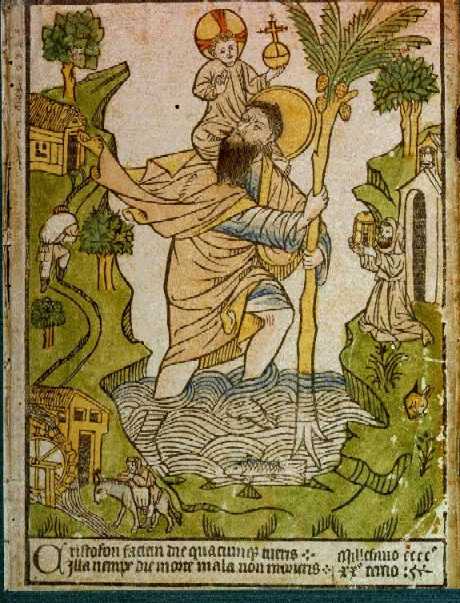

Relief. A relief is something standing proud, e.g. potato printing. A woodcut is similar in that the design is cut from a block of wood, such as

boxwood or some other fine grained wood. Simple linear designs. Note all the white is cut away. It can become a very skilled process

when there are many close lines. You cannot print tones in this way. Modelling can only be done by hatching. The only tone and colour is hand

coloured afterwards.

We generally do not know where woodcuts come from or when they were produced unless the book or print are dated.

But dates are misleading. Dates in early works can be all sorts of things. Prints without dates are guessed by comparing then with similar prints.

Can also look for other sorts of evidence such as a coats of arms. Paper was not produced in Europe before the 13th century and not in quantity till the 14th.

Before this date designs were printed on textiles. This is a repeating print of the same design.

Woodblocks are very durable so thousands of images can be made and not much pressure is needed which extends the life of the block.

Master of Flemalle, one of the first images in a domestic setting. Note there is a cheap print above the fireplace. Such prints were

small and cheap so appealed to a very wide public. Such prints had a function (for praying) so could be seen as a momento and devotional

image rather than a work of art. Bible of the Poor printed using woodcuts. Typology prefigurement, types.

Printing with movable type from 1450 onwards took over from woodcut printing. Woodcuts were cheaper initially.

Intaglio. Intaglio (“intalio”) means to cut into.

Engraving is a type of intaglio that involves scratching a line into a metal plate. The tool is a burin with a v shaped profile that is pushed.

Griffiths, Prints and Printmaking is a recommended look. Need to ink carefully so ink goes into grooves, then wipe plate, wet paper and

apply with reasonably high pressure. Put paper and plate through a thing like a mangle. So when paper dries it is slightly embossed and there is a plate mark.

Very difficult to date but the earliest were about 1440’s. Can get very fine lines and hatching,

Pisanello was very good at animals. Master of the Playing Cards – secular.

Master ES (as some of his prints have ES on them) is crucial in the development of the print.

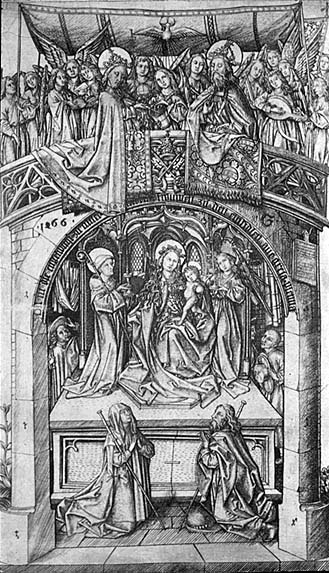

Cannot do shading but can vary tones with hatching, cross hatching and marks. Einsiedeln 900th anniversary of monastery.

The monestery is meant to have been founded by angels. Schongauer, extremely ambitions print.

Temptation of St Anthony was very famous and his prints travelled very widely across Europe.

Note images of devils predate Bosch. Durer travelled across Europe to meet him but he had died.

Drypoint. Drypoint same basic process but not a burin but a stylus that is dragged. It throws up a lot of burr (waste metal) that collects at the edge of the line.

This creates fuzzy lines. But the burr falls off after a few prints. Copper plate engravings last a long time but not as long as a woodcut.

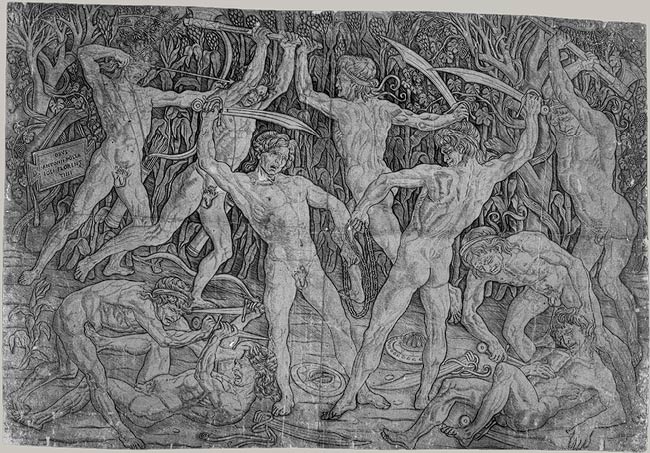

Two very famous Italian prints – Battle of the Nude Men, and Entombment. Does not serve a function other than to advertise the artist.

Mantegna survives in two versions so he added to the plate after the initial printing. Who makes the print. Engravings are done be artist,

printing left to a printer (except perhaps Mantagna). With woodcuts a craft developed to cut woodblocks.

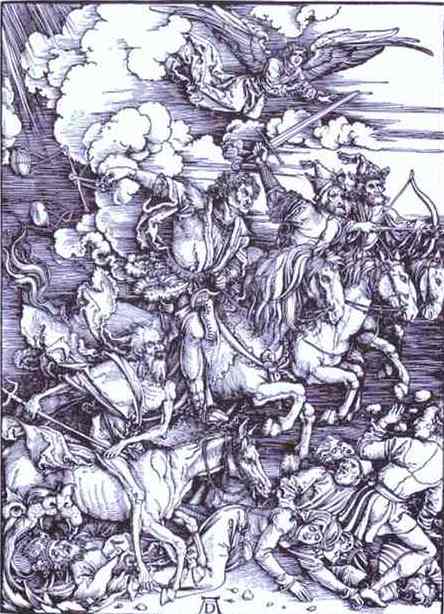

Durer published in 1498 his own book (his father-in-law was a printer and may have helped).

Very large and very dense woodcut. It is likely he designed the image and it was cut by someone else.

He would have drawn the design on the wood. The Large Passion was never published as a book. Melancholia cut it himself.

Subject to a lot of written commentary on symbolism and the humanist ideas of melancholy and the artist.

So he was commenting on the nature of the artist. The emergence of an artistic self-awareness

Famous double act of Raphael and Raimondi publicising Raphael’s designs. Sometimes an artist would draw an image specifically for an engraver to reproduce.

Raimondi copied Durer (i.e. he made a fake Durer) to make money. Including the monogram.

The woodcut tales off after Durer (athough it was used by the Expressionists).

Chiaroscuro woodcut (light/dark) are done with several blocks to print different colours. Laborious.

Etching. Rembrandt etching, the lines are cut using acid. First cover the plate in a resist then scrape through (easy, like drawing).

Then immerse in acid, take off resist and ink as for an engraving. Clean wipe means wipe plate, if this is not done then detail is lost but it is very dramatic.

This technique suggests Rembrandt made his own prints. See State V and State VIII of the same plate. Can erase by polishing the plate.

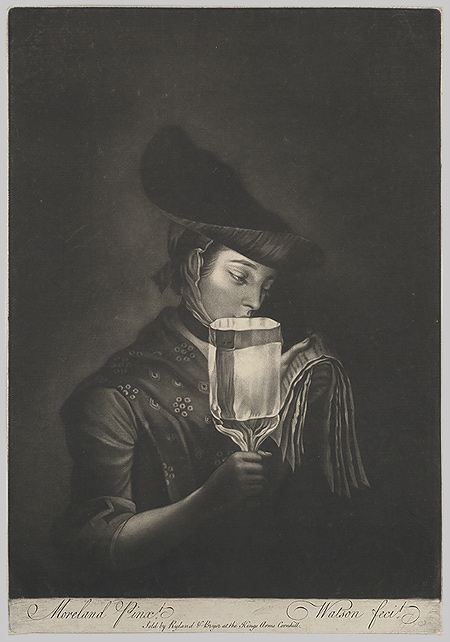

Mezzoprint. Mezzotint 18th century reproduction technique. Kitty Fisher as Cleopatra by E. Fisher (a different Fisher) was shown.

Copperplate mechanically roughened to create a mass of burr. Then selectively polish and this can create tone for the first time.

Highly skilled process produced by experts (not the artist) for reproduction for commercial reasons.

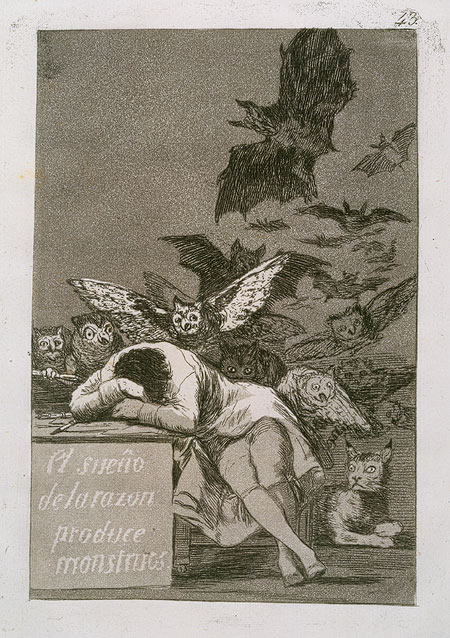

Aquatint. Aquatint is related to etching. Cover in a granular resist so the acid will eat though some parts more than others and create speckles.

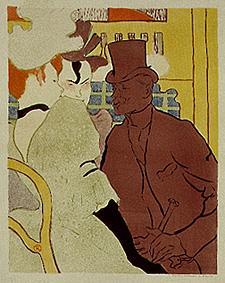

Can polish and scratch away indefinitely, Lithography Lithography is used commercial for posters in 19th century.

Uses a smooth stone and paint on a waxy substance that resists ink. Multi stage highly technical process that artists d not do carry out.

E.g cover everything except one area and print one colour, then repeat for second colour and so on.

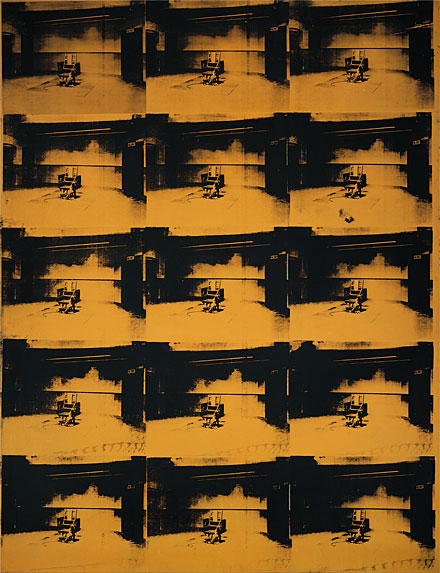

Screenprint. Warhol electric chair. Gauze mesh and photo sensitive gel that hardens on exposure to light. So protect the image and then wash of soft gel.

Relief- Woodcut

Slide 1: St Christopher. 1423 Woodcut

Slide 2: Christ on the Cross. c. 1430 Woodcut

Christ bearing the cross

schaufelein hans c1480-1539

New Testament

woodcut

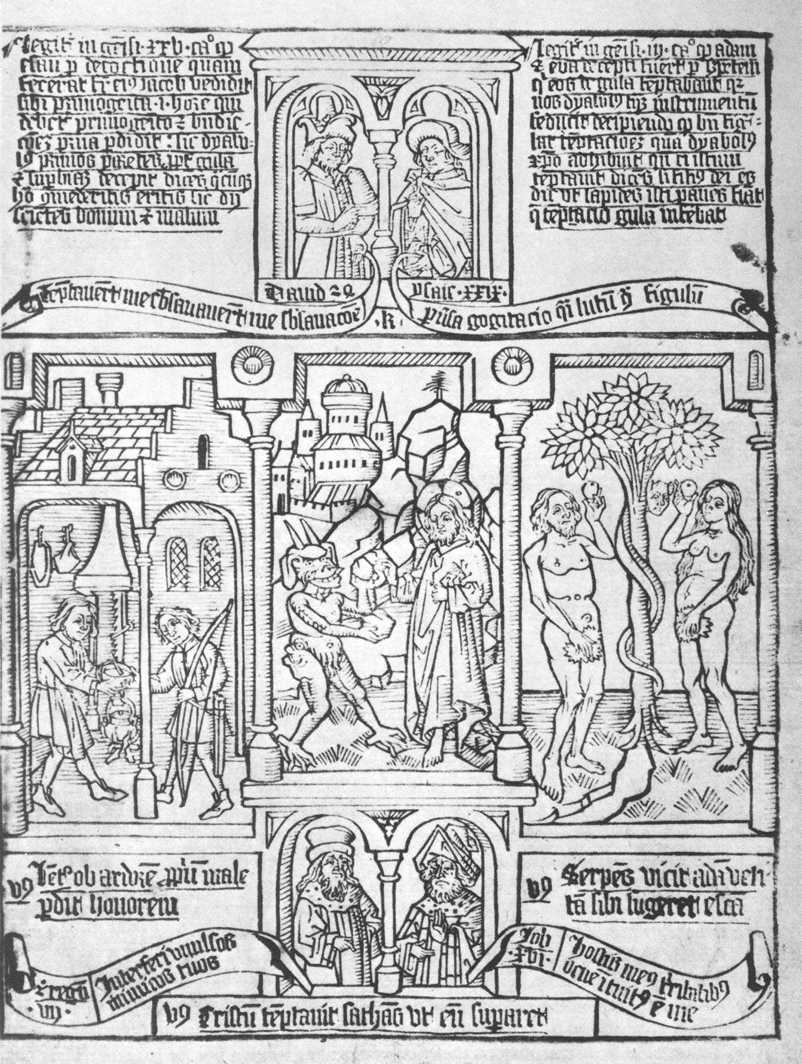

Slide 3: Crucifixion from a Biblia Pauperum Netherlands. c. 1465 Woodcut

Biblia Pauperum (Poor Man’s Bible)

1470

Woodcut, 280 x 213 mm

National Gallery of Art, Washington

The Biblia Pauperum was another of the famous block books published in many editions in Germany and the Netherlands. It rivaled the Ars Moriendi in popularity. Copies of this work were never really acquired by the poor layman, as the title of the work might suggest. In all likelihood, it was found in the hands of the poorer members of the clergy who could not afford the complete and expensive Bible. The illustrations deal with episodes from the life of Christ, some parallels from the Old Testament, and textual comments from the Prophets. The book generally consisted of some forty to fifty leaves, and in this concise form it satisfied the needs of a poor priest who sought suggestions and material for his preaching. From an artistic point of view, the crowded pages do not have the impact of the full-page illustrations of the Ars Moriendi; stylistically they are linked to the traditional handling in illuminated manuscripts dating from as early as the fourteenth century. During the late Middle Ages, the drawing of parallels between events and characters of the two Testaments had become a popular device. Each page of the Biblia Pauperum illustrates a subject from the life and Passion of Christ, two parallels from the Old Testament, and two witnesses from among Biblical personages. Thus, on the page dealing with the Resurrection of Christ, we also see the traditional parallels drawn from the narratives of Jonah and of Samson. On another page, depicting the Annunciation, the compartment to the left displays Eve in the Garden of Eden. In the woodcut illustrated here, we see the Temptation of Christ in the centre panel, Jacob and Esau on the left, and the Temptation of Adam and Eve on the right. The preacher was thus left a broad choice as to what use to make of these pictures and text for his sermon.

Slide 4: Master of Fl'malle Annuciation Mus'e des Beaux Arts, Brussels (search Google for image)

Slide 5: Master of the Playing Cards Nine of Birds. 1440s Engraving

Slide 6: Master of the Playing Cards Queen of Stags 1440s Engraving

Slide 7: Master ES Nativity. 1460s Engraving

Slide 8: Master ES Madonna of Einsiedeln. 1466 Engraving

Slide 9: Martin Schongauer (d. 1491) Temptation of St Anthony 1470s Engraving

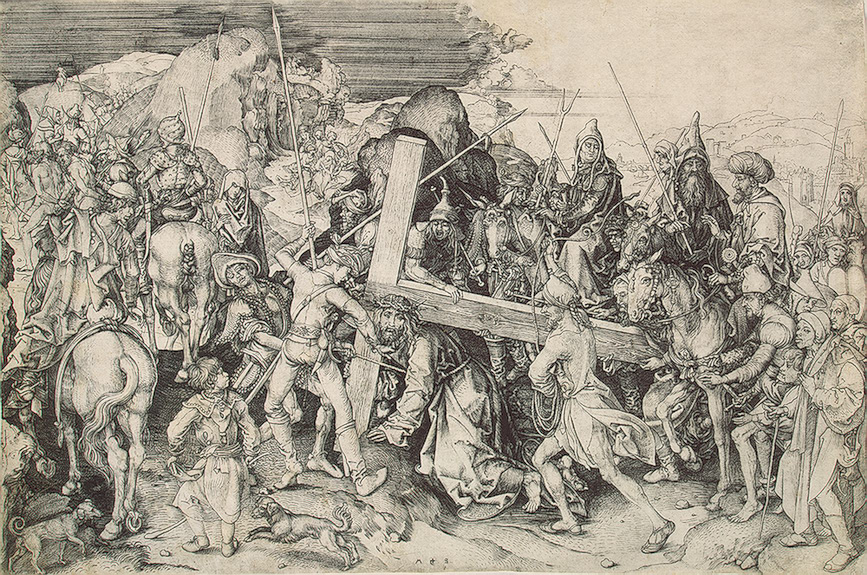

Slide 10: Martin Schongauer The Large Carrying of the Cross. 1470s Engraving

Slide 11: Housebook Master Holy Family Drypoint

The Holy Family with the Rose-bush c. 1490 Drypoint (unique impression), 142 x 115 mm Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam One of the most delightful and surprising depictions of the Holy Family is an etching by the Master of the Housebook, which survives in only a single impression. The family is outdoors, in an enclosed garden. In fifteenth-century Rhineland art, the Virgin and Child are often depicted in this hortus conclusus, (a garden close-locked) that symbolizes Mary’s virginity, sometimes with a rose hedgerow, another of the Virgin’s symbols. Almost every landscape detail in this etching is a Marian symbol that features in one or more hymns to her. There is the church in the background, of course, but there is also a tower, the turris Davidica, and on the left the gateway to Heaven, the porta coeli. The harbour in the background may be a reference to Mary as a safe haven, the apple tree beside the roses may allude to Original Sin and to the redemptive roles of Mary as the new Eve and Christ as the new Adam. All of these motifs can be read symbolically, and probably were by some of the artist’s contemporaries. However, there is an enormous difference between this and earlier scenes incorporating symbols. Garden, bench, gateway, tower, harbour and church are no longer isolated motifs, but together form a natural setting for this scene of family domesticity. The viewer can recognise their world as his own. That this naturalness was deliberate is particularly clear from Joseph’s involvement with Jesus. He has been given a role halfway between simpleton and paterfamilias. He is no longer a marginalised, ineffective doubter, but a playful father interacting with his son. He is impishly distracting Jesus’s attention by playing a game with the love apples from the Song of Songs. Jesus has lost His usual role as the Saviour communicating with the viewer, or as His mother’s child. The landscape and the addition of Joseph are above all an attempt to create a suitable setting for an intimate scene of family life, one in which the believer devoutly saying his prayers can feel involved.

Slide 12: Antonio Pollaiuolo (1432-98) Battle of the Nude Men Engraving

Battle of Naked Men, 1465

Antonio Pollaiuolo (Italian, Florentine, 1431 / 32 – 1498)

Engraving; 15 1/8 x 23 3/16 in. (38.4 x 58.9 cm)

Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1917 (17.50. 99)

Slide 13: Andrea Mantegna (1430/1-1506) Entombment Drypoint (search Google for image)

Invention and Execution

Slide 14: Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse from the Apocalypse 1498 Woodcut

Slide 15: Albrecht Durer Christ Carrying the Cross from the Large Passion. 1497-1510 Woodcut

Christ on the Mount of Olives / The Agony in the Garden (B. 6, Strauss 38, M. 115 c). Original woodcut, c. 1497-1500. One of Durer ‘s earliest major prints, this work was one of the first to reveal his genius. Originally made for Durer’s Large Woodcut Passion, this is one of Durer ‘s most dramatic prints.

Slide 16: Albrecht Durer Melancholia I. 1514 Engraving

Slide 17: Raphael (1483-1520) Jupiter and Cupid, Farnesina, Rome

Slide 18: Marcantonio Raimondi (c. 1480-1534) Jupiter and Cupid (after Raphael) Engraving

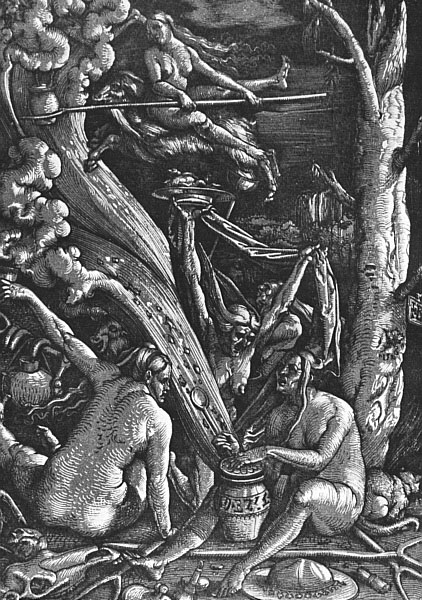

Slide 19: Hans Baldung (1484/5-1545) Witches Sabbath 1510 Chiaroscuro woodcut

Slide 20: Ugo da Carpi (d. 1532) Diogenes Chiaroscuro woodcut

Etching

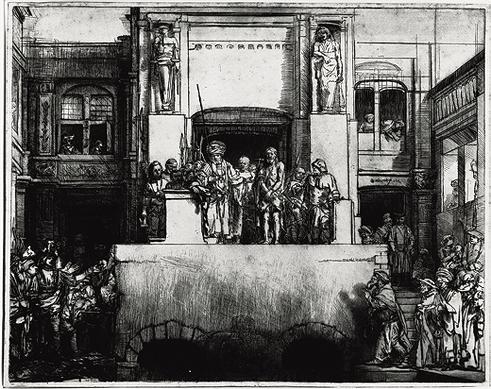

Slide 21: Rembrandt Presentation in the Temple. c1654 Etching with drypoint. Clean-wiped

Slide 22: Rembrandt Presentation in the Temple Etching with drypoint Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn

(Dutch 1607-1669)

Presentation in the Temple

etching and drypoint, 1640

8 1 / 2 x 11 1/2

[ text:

Rembrandt van Rijn is indisputably one of the great masters of printmaking. To discuss his full capacities as an artist in a single entry would do him little justice. However, in discussing The Presentation in the Temple, a brief sketch of his printmaking techniques and subject matter is required. During his lifetime, Rembrandt made more than two hundred prints. The Presentation is done in the style of The Hundred Guilder Print, produced in 1639. 1 That time period marks a transition from Rembrandt ‘s earlier style and experimental years to the style of his later years when he had full command of his etching and drypoint technique. Up until 1640, Rembrandt had achieved tonal gradations mainly through multiple acid bitings (sometimes using vinegar). He used drypoint only for final touches. By the time of The Presentation in the Temple, Rembrandt had investigated to its limits the process of pure etching and increasingly used the drypoint technique. 2 His ability to successfully blend these techniques frequently makes it impossible to determine the difference between the two. The Presentation in The Temple can be considered one of his first prints that used the drypoint technique to fully carry the intention of the print. With it, he could easily create the shadowy, dark areas seen in this print and others done in the same manner.

The Presentation is an example of the many prints that Rembrandt executed from stories in the Bible. At least one – third of his work is devoted to biblical subjects, quite surprising considering the influence of Calvinist theology in the Netherlands. 4 Typical of Reformation iconoclasm, Calvin ‘s teachings devalued the representations of biblical figures. Rembrandt, however, was religiously independent all his life. He may have inherited a deep spirituality from his mother, whom Rembrandt often represented holding a Bible. 5

The Presentation in the Temple is a subject that obviously interested Rembrandt greatly….

Slide 23: Rembrandt Christ presented to the People. State V Etching. 1655

Slide 24: Rembrandt Christ presented to the People. State VIII Etching

Mezzotint

Slide 25: Valentine Green after Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-92) Mary Isabella, Duchess of Rutland Mezzotint 1780

Valentine Green after Sir Joshua Reynolds

Lady Elizabeth Compton, 1781

Slide 26: James Watson after Sir Joshua Reynolds The Honourable Mrs Bouverie and her child. 1770 Mezzotint

A Girl Singing Ballads by a Paper Lanthorn, after 1767 — before 1782

Thomas Watson (British, 1743 – 1781) after Henry Robert Morland (British, 1716 ?' 1797)

Mezzotint; 12 3/4 x 9 in. (32.4 x 22.9 cm)

Aquatint

Slide 27: Francisco de Goya (1746-1828) Who would have believed it? Aquatint

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters: Plate 43 of The Caprices (Los Caprichos), 1799

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Spanish, 1746 – 1828)

Etching, aquatint, drypoint, and burin; Image: 8 7/16 x 5 7/8 in. (21.5 x 15 cm)

Surface-Lithography

Slide 28: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) Englishman at the Moulin Rouge. 1892 Lithograph

Screenprint

Slide 29: Andy Warhol (1928-87) A Lavender Disaster. 1964 Screenprint

Orange Disaster #5, 1963. Acrylic and silkscreen enamel on canvas, 106 x 81 1/2 inches. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Gift, Harry N. Andy Warhol announced his disengagement from the process of aesthetic creation in 1963: 'I think somebody should be able to do all my paintings for me,' he told art critic G.R. Swenson. The Abstract Expressionists had seen the artist as a heroic figure, alone capable of imparting his poetic vision of the world through gestural abstraction. Warhol, like other Pop artists, used found printed images from newspapers, publicity stills, and advertisements as his subject matter; he adopted silkscreening, a technique of mass reproduction, as his medium. And unlike the Abstract Expressionists, who searched for a spiritual pinnacle in their art, Warhol aligned himself with the signs of contemporary mass culture. His embrace of subjects traditionally considered debased'from celebrity worship to food labels'has been interpreted as both an exuberant affirmation of American culture and a thoughtless espousal of the 'low.' The artist's perpetual examination of themes of death and disaster suggest yet another dimension to his art. Warhol was preoccupied with news reports of violent death'suicides, car crashes, assassinations, and executions. In the early 1960s he began to make paintings, such as Orange Disaster #5, with the serial application of images revolving around the theme of death. 'When you see a gruesome picture over and over again,' he commented, 'it doesn't really have any effect.' Yet Orange Disaster #5, with its electric chair repeated 15 times, belies this statement. Warhol's painting speaks to the constant reiteration of tragedy in the media, and becomes, perhaps, an attempt to exorcise this image of death through repetition. However, it also emphasizes the pathos of the empty chair waiting for its next victim, the jarring orange only accentuating the horror of the isolated seat in a room with a sign blaring SILENCE. Warhol's death and disaster pictures underscore the importance of the vanitas theme'that death will take us all'in his oeuvre. Self-Portrait, one of the last self-portraits Warhol painted before his death, may be considered the anxious meditation of an aging artist. (Other works he painted in his final year include a posthumous portrait of Joseph Beuys, who died in 1986, and a rendition of Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper.) The monumental scale of Self-Portrait suggests that Warhol's obsession with celebrity encompassed himself. Yet unlike nearly all of his portraits, which commonly include the sitter's neck and shoulders, this otherworldly image presents the artist as spectral, his acid green, disembodied head like a skull looming out of the black background.