Quotes

1. Account book of Francis Manners, 8th Earl of Rutland for 1617 1619:

‘Paid Larkin, picturemaker, for a picture, 301, formerly paid 101, rest 301.’

‘Paid to William Larkin, picturemaker, for my Lady Katherine’s picture, in full paiment of 301…’

2. Edward Herbert, first Baron Herbert of Cherbury, in his autobiography (printed in I. Buxton, Elizabethan Taste (London, 1963), p.120):

‘There was a lady also, wife to Sir John Ayres, Knight, who, finding some means to get a copy of my picture from Larkin, gave it to Mr. Isaac the painter in Blackfriars, and desired him to draw it in little after his manner; which being done, she caused it to be set in gold and enamelled, and so wore it about her neck so low that she hid it under her breasts.

coming one day into her chamber, I saw her through the curtains lying upon her bed with a wax candle in one hand, and the picture I formerly mentioned in the other. I coming thereupon somewhat boldly to her, she blew out the candle, and hid the picture from me; myself thereupon being curious to know what that was she held in her hand, got the candle to be lighted again, by means whereof I found it was my picture she looked upon with more earnestness and passion than I could have easily believed.’

3. Edward Herbert, first Baron Herbert of Cherbury, in his autobiography describes a visit to the Earl of Dorset at Dorset House in London:

‘… where bringing me into his Gallery, and showing me many Pictures, he at last brought me to a frame covered with green Taffata, and asked me who I thought was there; and therewithal presently drawing the Curtain, shewed me my own Picture; whereupon demanding how his Lordship came to have it, he answered, that he had heard so many brave things of me, that he got a copy of a Picture which one Larkin a Painter drew of me, the original whereof I intended.., for Sir Thomas Lucy.’

4. Among the chorus of disapproval against male courtiers’ fashion following James I’s abolition of the sumptuary laws, Barnably Rich wrote in 1614:

‘And from whence cometh . . .this curiositie that is used amongst men, in freziling and curling of their hayre, this gentlewomanlike starcht bandes, so be-edged and be-laced, fitter for Mayd Marion in a Moris Dance, then for him that hath either that spirit or courage that should be in a gentleman.’

We can see Jacobean tomb sculpture in Westminster Abbey and churches up and down the country. For example,

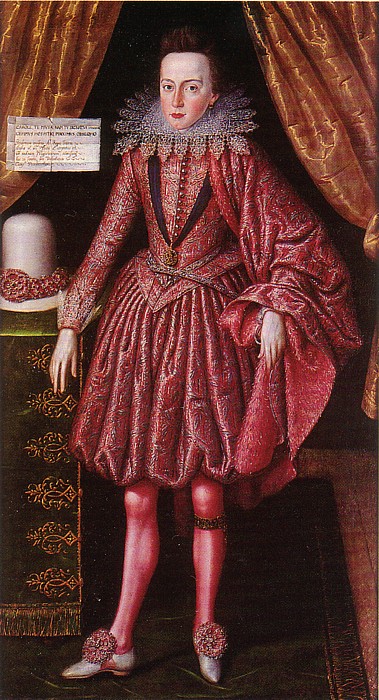

Diana William of Cecil 1610-14, William Larkin, compare with the outmoded:

Elizabeth I, 1599-1600, Hardwick Hall portrait, possibly by Nicolas Hilliard. Larkin was an Elizabethan and died in 1619 but he started to introduce the changes we see picked up later. Common to both pictures is the pose, an interest in fashion meticulously presented, rich Turkey carpets, bother are standing next to X-frame chairs although Elizabeth’s is more ornate and has an embroidered cushion. To understand just how expensive these chairs were when the Spanish ambassador and his entourage arrived at court to negotiate a peace treaty they ran out of chairs and had to borrow some from a local nobleman. Both pictures have a flattened look with minimum shadows.

Henry, Prince of Wales, Marcus Gheeraerts, 1605 (National Portrait Gallery). Note the curtains are the same as the Larkin picture and it has a fringe like most Larkin pictures (although not this one).

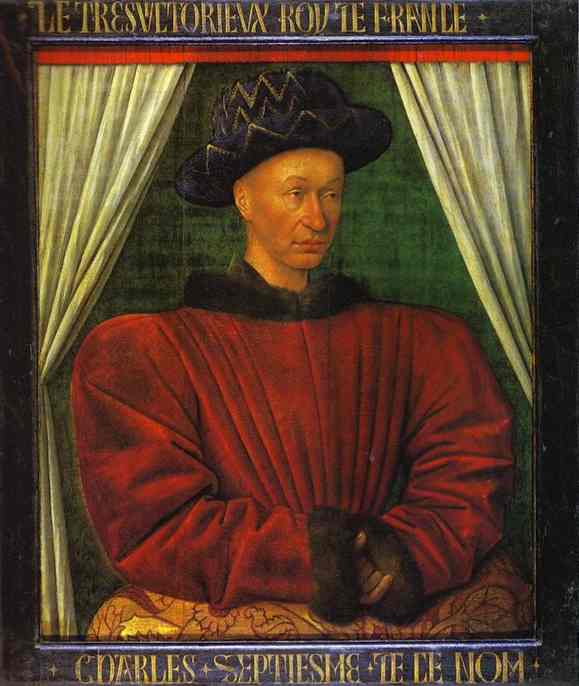

The use of framing curtains was common across Europe and were used much earlier

(for example, Charles VII, King of France, Jean Fouquet (1415/20-1480) had a pelmet and curtains).

Did the curtains represent power? Or were they trompe l’oeil for the actual curtains used in front of pictures. Were they liminal curtains that showed another world that only the sitter had access to? Curtains were also used in miniatures.

Being painted by Larkin was trendy and he painted most of the rich and famous at the time.

Richard Sackville, Earl of Dorset, Isaac Oliver, 1616. This portrait look Elizabethan so looks like a Hilliard but Isaac Oliver’s monogram is on the curtain. The pose and the face are natural but the tilted floor is archaic, Oliver was a master of perspective but Hilliard was not. So what is going on here? Possibly the patron asked for this style (but how did he ask – give me a tilted floor?). More likely Oliver was asked to copy an existing portrait by Hilliard. Compare with Larkin’s version:

Richard Sackville, Earl of Dorset, Larkin, 1616.

The body is stiff but the face is well modelled. We find stylized hands in Larkin. This may be because he only used the sitter for the face and created the rest from models and drawings. See quote 2 above, we see the Earl of Dorset was very vain. Note he gets a portrait from Larkin and gives it to Mr. Isaac to copy.

Lord Herbert of Cherbury, Isaac Oliver, 1613-4, still at Powys Castle. The pose is typical of Elizabethan romanticism and melancholia, under a greenwood tree by a babbling brook in contemplation.

Portrait by Larkin for Sir Thomas Lucy, 1609 of Herbert of Cherbury, still at the same house, full size. Painted on copper, Larkin painted a few on copper, a few on wood but mostly on canvas.

See quote 3 about the green taffata curtain.

Were there copyright issues? There were issues of copying. Durer complained of copying and developed his AD monogram but even this was copied.

Lady Anne Cecil identical dress and pose to Lady Elizabeth Cecil, her sister, Larkin. It is in good condition and the colours are intense. Not dated but about c. 1614-8. They were sisters and the paintings may be pictures of when they were both brisesmaids for their third sister’s wedding and they may therefore be wearing bridesmaid’s dresses.

See quote 1, 1617-19 a payment to Larkin of ’30, this was a lot of money, so surely it was for a full length portrait. There were only three types – head and shoulders, three-quarter length and full length.

Could Larkin have streamlined his workshop to speed up production? For example, someone who specialises oin curtains, someone in srpaery and so on. A drawing of curtains would be copied from painting to painting. Early Netherlandish painters used stencils and pouncing to produce identical Virgin Marys. In Larkin’s paintings the same carpet appears 10 times. Note the carpet of the Earl of Dorset has black dots around the yellow to indicate stitching but it is unfinished, maybe the painting was needed urgently.

Marquess of Suffolk, Larkin, Kenwood, different coloured curtains.

Technique was very labour intensive. Perfection of the surface comes from a double thick ground of chalk in animal glue, scrapped down twice. Larkin uses a much thicker mixture than normal a “glacial surface” (as Roy Strong describes it). that is still brilliantly reflective.

Anne Leyton, Lady Saint John, Maple Durham House, c.1615019, attributed to Larkin. A beautiful landscape, more meticulous than the 1590s landscapes. We don’t know if it was topological. Did Larkin paint the landscape or employ a specialist? We don’t know as it is the only one with a landscape. There is a different presentation of the sitter. Is the skull on the bank a memento mori? Did her husband die? The skull is usually placed next to the person who died. She could be a melancholic as it was the fashion from the 1580s to the early 17th century, Shakespeare is full of references and characters such as Hamlet. This could be a very unusual case of a female melancholic. She has folded arms which is typical of the melancholic (as described by Shakespeare). The landscape is painted in subdued colours, with aerial perspective. Cherbury was also a melancholic, head on hand.

Melancholia was a huge cultural trend that started in Italy (Burton’s “The Anatomy of Melancholia” is an enormous volume describing it, the frontispiece is a figure with folded arms beneath a tree with a garden behind). There are tow types of melancholia:

- Unrequited love – unbuttoned shirt.

- Lost in intellectual thought.

Suffers were said to be under the influence of Saturn, dark, depressive, moody state from which it was thought creativity arises – “genius akin to madness” comes from this.

Larkin, Portrait of Mary Radclyffe, 1610-13

A follower of William Larkin, Three Young Girls 1620.

Larkin, said to be Lady Waugh, c.1615. Larkin had many rich and famous patrons:

Countess of Suffolk (whose son married the sister of the two women who could be bridesmaids).

Duke of Buckingham (National Portrait Gallery, 1616, Larkin), was a major patron of the arts and Rubens, and he had an enormous collection, but he was universally loathed. He was the impoverished second son of a Leicestershire squire but was the best looking man of the age. James favourite was Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset, but he was politically inept so a group of rival courtiers alighted on George Villiers and pushed him before James I in 1614. In a few years he had risen from Knight to Viscount to Marquis to Earl to Duke. Villiers married the daughter of the Earl of Rutland (mentioned in quote 1).

Larkin, Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke c1615. Earl of Pembroke (who pushed Villiers forward). His son was painted by Larkin in 1616. It is the best preserved portrait.

Between 1617 and 1619 all the old generation of artists and collectors died:

- 1617 – Isaac Oliver died

- 1618 – Hilliard died

- 1619 – Larkin died, Robert Peake died, Anne of Denmark died

A new generation of painters come from the Netherlands, the best known were:

- Paul Somer (“Zomer”)

- Daniel Mytens

Paul Somer

Paul Van Somer circa 1577 or 1578 – circa 1621 or 22. He came from Antwerp but travelled widely around the Netherlands including Amsterdam and Den Hague. By December 1616 he had settled in London and died in 1621-2 and is buried in St. Martins-in-the-Field. So we are only interested in a few years period. When he arrived he got royal commissions immediately.

There are three versions. This is signed and dated 1617 and is the best version and is in the Royal Collection. Oaklands Palace (her house) in 1617 is in the background. She lived there with her court as she was estranged from James I as he was chasing young men. The wall and arch in the painting are by Inigo Jones 1617, and we have the drawings. It is far more natural, there is a narrative. Note the black servatn which at the time was a status symbol. She shows movement, she is leaning back and her leg is moving forward, the dogs are jumping. This is one of the first portraits with animals. The dogs have collars inscribed AR (Anne Regina). Anne was a Catholic convert (even worse from a Protestant point of view) and she had the right to attend mass. The text on the scroll in the sky is Italian for “My Greatness Comes From God”, her personal motto. She also has this motto in an earlier painting by Marcus Gheeraerts and in prints. In 1618 in a letter it said “she is the daughter, sister and wife of a king which cannot be said of any other and she claims her greatness comes not from the king but from God.”

This is an independent portrait not a pendant because she is facing the right. The dominant side is always the left as we look at it (the heraldic right). The husband at this time was always shown on the left.

There is weather in the sky. It may owe some debt to this painting by Robert Peake, 1603, Prince of Wales.

Van Somer also painted the King in 1618. Compare John de Critz of 1606 – a similar stance, but the feet are firmly placed in the later picture, his head looks heavier and more plastic.

Somer, Lady Elizabeth Grey, Countess of Kent circa 1619

Daniel Mytens

Matriculated in Den Hague.

Michiel Jansz. van MIEREVELD, Dutch painter (b. 1567, Delft, d. 1641, Delft), Prince Maurits, Stadhouder, c. 1625, Oil on panel, 220 x 140 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam Miereveld, Sir Edward Cecil, unknown woman (National Portrait Gallery)

The school of Den Hague was very lifelike, strongly modelled, very powerful.

Self-portrait, Mytens, Royal Collection.

Portrait of James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, Later 3rd Marquis and 1st Duke of Hamilton, Aged 17 1623

Alatheia Talbot Countess of Arundel by Daniel Mytens, c.1618. (National Portrait Gallery, London). Earl of Arundel and his wife. This is an important pair of paintings as it shows an early art collection.

Countess of Monmouth, Mytens, a real woman. Marcus Gheeraerts, unknown lady, like a stiff doll in comparison.

Earl of Monmouth, Mytens.

Prince of Wales, 1623, Mytens.

Mytens, Charles Howard 1st Earl of Nottingham, c1620

Daniel Mytens, The First Duke of Hamilton, 1629. Earl of Arun, 1623, James Hamilton (Tate Britain) went with Charles to Spain to woo the daughter of the King of Spain. He saw Velasquez portraits, is this why he asked Mytens to paint him in black with a dark background (as in the Spanish Courts). James Hamilton, later, tradition of Van Dyck and baroque. Best he did just before van Dyck arrived which was the death knell for van Mytens and although he stayed in England for a few years he eventually went back to Holland. He is the key precursor to van Dyck.