Portrait miniatures started during the early Tudor period. The V&A miniature gallery should be visited to see examples.

In 1603 James I became king and artists were delighted as he spent on art. He boasted about his wisdom, ‘the new Solomon’. He was highly educated and could read Latin, Greek and some Hebrew (which was very unusual). He was interested in architecture and had plans to rebuild London. He came with a family (each member of which would have a court artist when they came of age). His wife was Queen Anne of Denmark.

He believed in the divine right of kings and was very autocratic. There are many stories, for example, when the King of Denmark visited they both got so drunk they were crawling on the floor and are said to have knighted a side of beef giving rise to the term ‘sirloin’. He enjoyed male company and was bisexual. He had favourites and this explains the rapid rise of the Duke of Buckingham. This brought him into disrepute.

He had a bad press – there is a well known account that was written by a disgruntled courtier and this scurrilous attack survives and was used by historians up to the 1950’s as fact. The two great competing artists were Nicholas Hilliard and his pupil Isaac Oliver (see Hilliard). One set of miniatures by both artists shows:

- James I

- Queen Anne of Denmark

- Henry (d. 1612)

- Charles

- Elector Palatine

- Elizabeth (married Elector Palatine, King of Bohemia). Elizabeth was known as the Winter Queen.

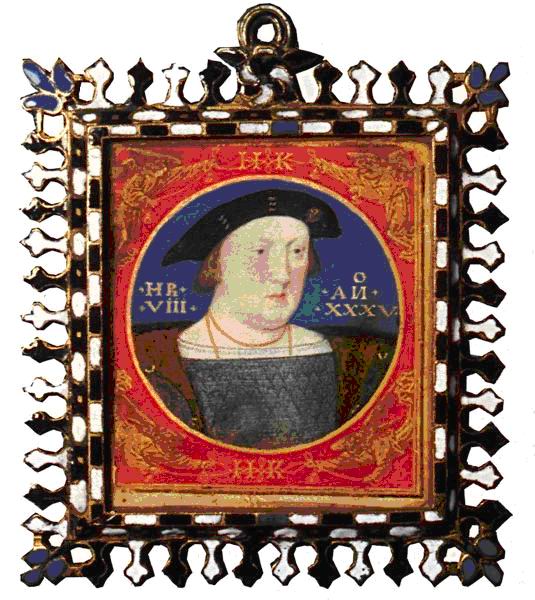

The miniature was invented in the 1520’s. The earliest known is the young Henry VIII by Lucas Horenbout in Cambridge.

The miniature came out of manuscript illumination (someone had the idea of cutting a portrait out of the manuscript). This miniature was painted on a square piece of vellum as a round image in the centre surrounded by a painted frame.

Its heyday was in the 1580 and 1590s and when James came to the throne its use continued. It is a unique art form because:

- It has an intimacy, you have to pick it up and hold it close to see it.

- It is round or oval and inscribed with text.

- They were displayed in cabinets, as jewellery or lockets that were worn around the neck or waist.

- They were portable.

- They could be worn from a belt or chain or pinned next to the heart.

- They were usually covered so were secret.

- They were popular gifts, lover’s tokens, and used as part of courtly love (particularly in Elizabeth’s court).

- They were given as a gift to show favour (without the gold case in Elizabeth’s case).

- By mid-16thC they were no longer round but oval.

- In the 16thC oil paintings usually had curtains (yellow and purple stripes) so there was a degree of intimacy even with these large portraits.They provided a close-up view of the person, unlike a painting.

- They were not painted in oils but coloured pigment mixed with gum Arabic or egg white (glair).

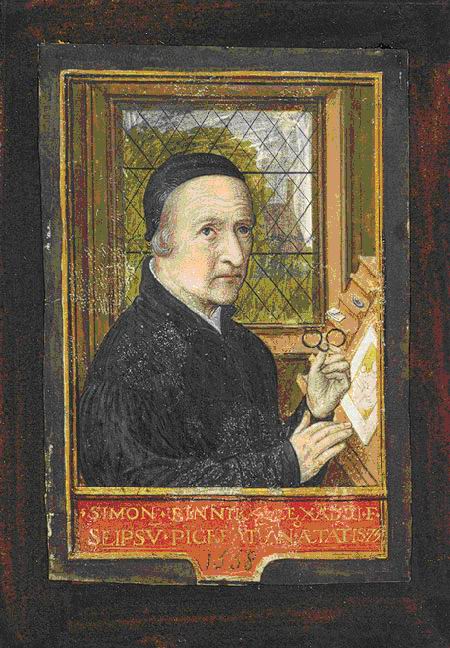

In 1558 Simon Bening self-portrait of an artist at work, self-portrait, 1558, Simon Bening (Netherlandish, born ca. 1483/84, died 1561), tempera on parchment, 3 3/8 x 2 1/4 in. (8.6 x 5.7 cm), Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.2487)

The drawing board is set at a steep angle near a window and he holds glasses. They did not usually wear glasses or use magnifying glasses to work they held the picture very close to their eyes.

The surface is vellum, it was pasted onto a playing card (as this was the best card available) and the back was white.

1540 Hans Holbein has playing card visible on the back.

Holbein, Hans the Younger (b. 1497, Augsburg, d. 1543, London), Portrait of Jane Pemberton, c. 1540, vellum mounted on playing card, diameter 5.3 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

An unfinished painting of an unknown lady shows the order of painting. The background was painted first. First the ‘carnation’ (a reddish-brown layer for skin tones) was painted directly onto the vellum. Red and grey hatching strokes were used for the skin. The back ground is flawless -they exploited surface tension – the area was covered in water and then blue pigment was touched onto the surface and water tension spread the colour out

smoothly without brushing.

Ann Lovell we now know was the Holbein Lady with a Squirrel.

Nicholas Hilliard 1547-1619, self-portrait aged 30, dated 1577, watercolour on vellum, stuck to a later piece of card.Inscribed either side of his head in Latin, ‘Year of Our Lord 1577 / At the age of 30 / NH’

In England, painters such as Hilliard were treated as mere tradespeople. But this confident self-portrait was painted during his two years in France where painters had a higher social status.

Nicholas Hilliard, self-portrait in V&A 1577, he was then the most important miniature artist, aged 30. He had a virtual monopoly on Elizabeth although she never made him official court painter to save money.

Miniature of Elizabeth I by Nicholas Hilliard, c.1595-1600. (Ham House), 1600 Elizabeth I, close-up. Every tiny detail of the ruff is shown. The paint is dribbled on an shows raised under raking light.

Hilliard wrote a book in 1600 that mentions the technique of painting jewellery (A Treatise Concerning the Art of Limning). They did not use the word miniature but limning (from illumination). Blobs of red resin on a pin were stuck onto silver (gold leaf gives sparkle but is more expensive, silver oxidises). The black blobs on the pearls were silver reflections rather than what now looks like frog’s spawn.

Jacobean patrons wanted extreme detail even in large-scale oil painting.

Limning was more spontaneous as water colour dried quickly. Some painters such as Hilliard, but not Holbein, painted with the sitter in front of them. Hilliard recommends trying to catch a fleeting moment, such as a smile. Elizabeth I sat for Hilliard and Hilliard says she engaged in a long conversation about the art of painting.

Close-up and intimate, a lady with a large round ruff that fills the space.

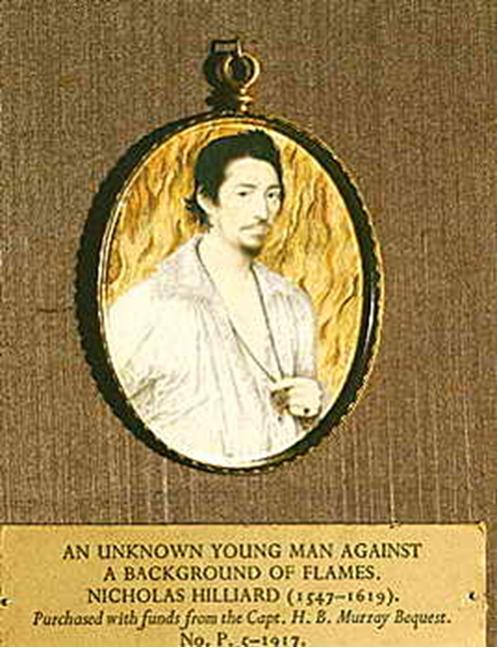

A portrait of an unknown man surrounded by flames (the passion of love) holding a miniature of his lady’s face close to his heart. It has powered gold in the paint which can be seen sparkling in certain lights. He is only wearing a vest which would never be seen in a large oil painting. (see Guardian story )

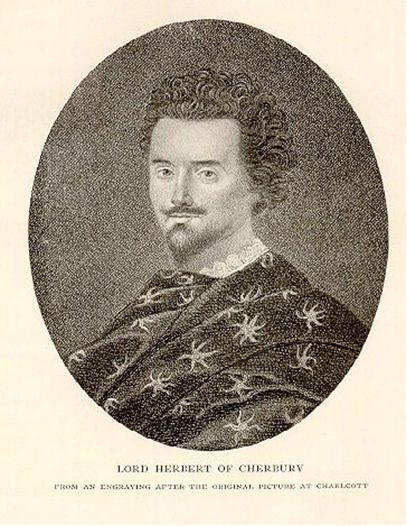

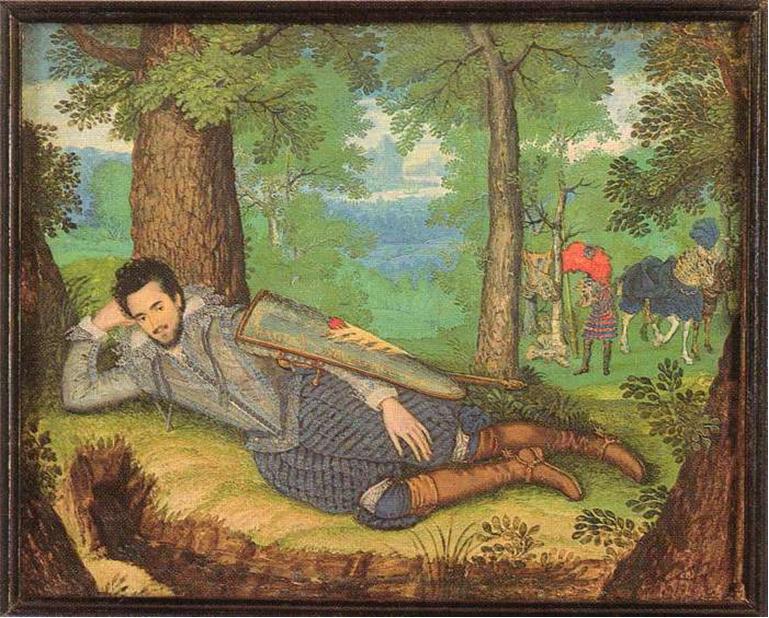

Miniature of Lord Herbert of Cherbury by Isaac Oliver (1556-1617), 1609-10, 18.1 x 22.7 cm, Powis Castle, a National Trust property near Welshpool, Powys

Edward Herbert, 1st Baron Herbert of Cherbury (or Chirbury) KCB (3 March 1583 – 20 August 1648) was an Anglo-Welsh soldier, diplomat, historian, poet and religious philosopher of the Kingdom of England. He is often called ‘The Melancholy Knight’ and he here adopts the pose of the melancholic, lying down contemplating the natural world.

Mostly we do not have the original setting. This is also true of oil painting and it is because fashions change and new owners replace old-fashioned frames.

Gresley jewel, private collection, 1585, shows how exotic the lockets were with pearls, gems and inlaid enamel. There is a cameo of an African woman on the reverse. This was quite common because the onyx stone is layered with white and dark layers and it was an obvious use of the material, or was it Imperial aspirations/ Inside the locket are Mr & Mrs Gresley.

1580 portrait of a lady wearing a miniature attached to her wait on a ribbon.

Francis Drake has the Drake Jewel (it still survives) tied around his waist. It has a black African profile with a white lady behind. It opens downwards to show Elizabeth I the tradition is she gave it to him. There is a phoenix in the lid, a symbol of Queen Elizabeth I.

The patrons valued the setting much more than the portrait as they cost more. A setting cost a few hundred pounds but a miniature was £1 to £5.

The Elizabethans looked at the visual arts from a monetary point of view so tapestry and gold were highly valued and painting was of low value. Painting and artists were much more highly valued in France. This began to change in the court of James I and changed completely in Charles I court. Patrons then vied to buy the highest quality works by Titian and Raphael. This taste we have inherited today.

Hilliard was the son of a goldsmith. He is made a court painter, the King’s Limner, when James comes to the throne. James hated having his portrait painted. Elizabeth had a chat with Hilliard about painting. So with James we get endless copies of standard face paintings that don’t change for 20 years.

Miniature of Mrs. Pemberton (Jane Small), c. 1540, Holbein

Gold pin heads on the side and what may be a lined partlet. Displays the same

folded linen shawl and interesting headwear that is similar to some of Holbein’s

non-English portraits. High-necked blackwork chemise with ties at neck instead

of button.

Mrs Jane Small (card on back) was the wife of a rich merchant who commissioned Holbein. Merchants and minor gentry had portrait miniatures painted at Hilliard’s studio in Gutter Lane. He died in 1619.

Elizabeth I by Hilliard

1610 Princess Elizabeth, by Isaac Oliver.

1578 Alice Hilliard, has a blue background.

Laurence Hilliard (his 4th son) became the King’s Limner. Worked in the style of his father. He is rather mediocre, he got bored according to his father.

In 1625 Laurence does not stay on with Charles. The change in taste happened in his lifetime. Queen Anne and Henry stop using Hilliard and switch to Isaac Oliver. 1605 he was made Queen’s Painter for Limning. Anne loved painting and was a major collector, she had a real eye and her own court.

Isaac Oliver, About 1560-1617,Portrait of Anne of Denmark, Queen of James I, about 1612, watercolour on vellum, stuck to pasteboard

James Stuart married Anne of Denmark in 1589 when he was James VI of Scotland.She produced two male heirs, Prince Henry and Prince Charles, and a marriageable daughter, Princess Elizabeth.

Isaac Oliver – Queen Anne of Denmark.

In 1610 Prince Henry aged 16 is invested as Prince of Wales and given his own court at Richmond and St James Palace, London (where the Prince of Wales still lifes).

Isaac Oliver Prince Henry. Note tent in the background.

Frances Kingsmill, Mrs. Croker by Nicholas Hilliard, c.1580-85, (Victoria & Albert Museum)

Hilliard Lady Crocker, 1585.

Oliver had subtle graduations of colour, depicted in space with a curtain and a landscape behind. More of the body is depicted. Fully rounded, soft shadow modelling head. Soft focus hair and ruff.

Oliver is responding to Continental trends including Renaissance Italy.

References

http://www.answers.com/topic/portrait-miniature

Hans Holbein miniatures

Jane Pemberton

http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/h/holbein/hans_y/3miniatu/3pembert.html