The functional and medial contexts of paintings in the ‘Gothic North’

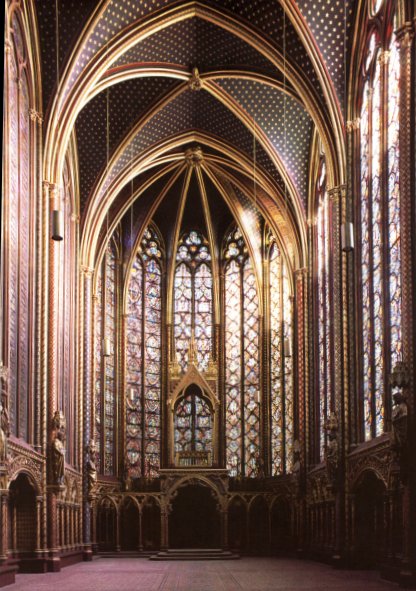

Slide 1: Paris, Ste-Chapelle, 1241-8

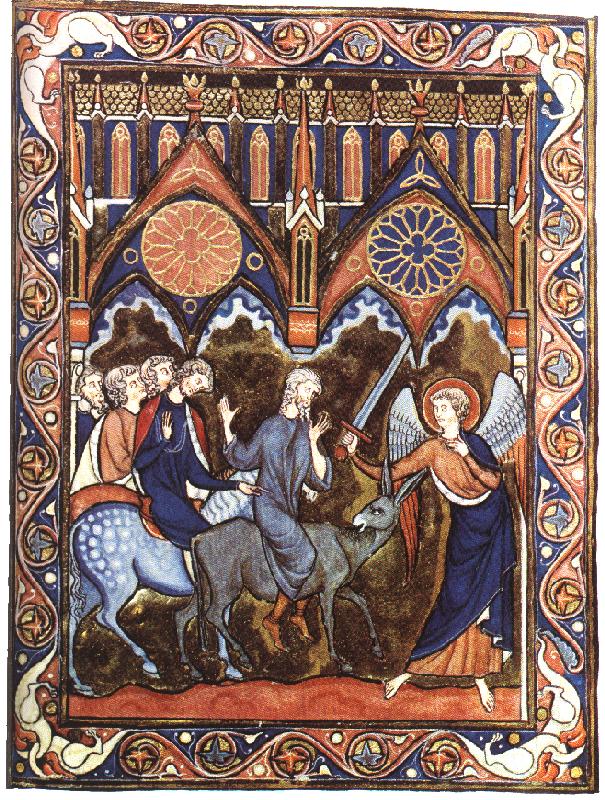

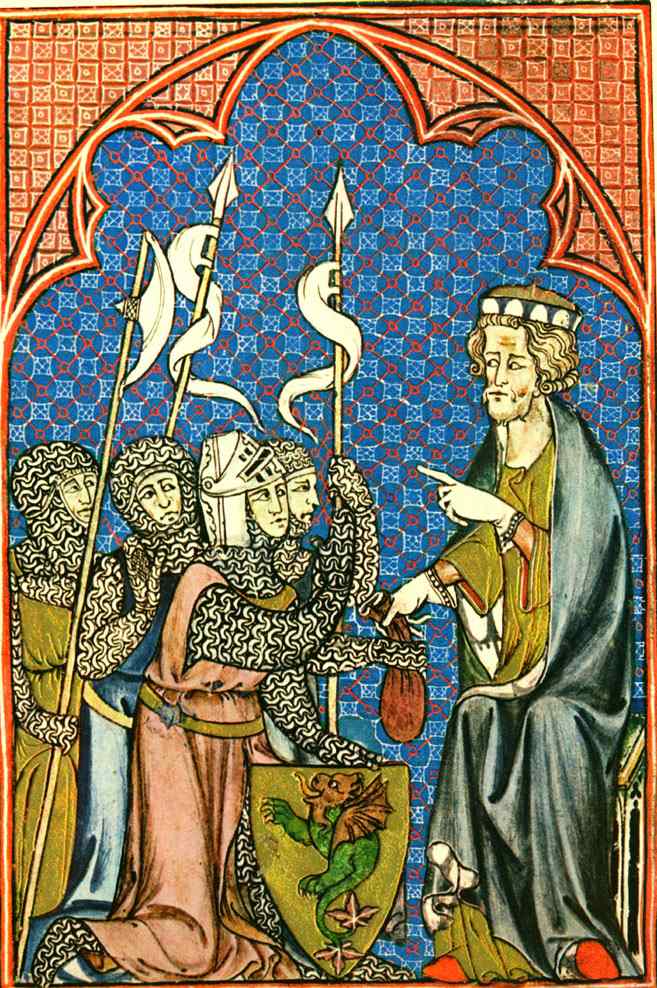

Slide 2: Psalter of St Louis, 1258/70, Paris, BN

Slide 3: Evreux (Normandy), Church of St-Taurin, shrine of St-Taurin, c. 1240

Slide 4: Westminster Abbey, Retable, c. 1270

Slide 5: Westminster Palace, Painted Chamber, former murals for Henry III, 1263/72(image not found)

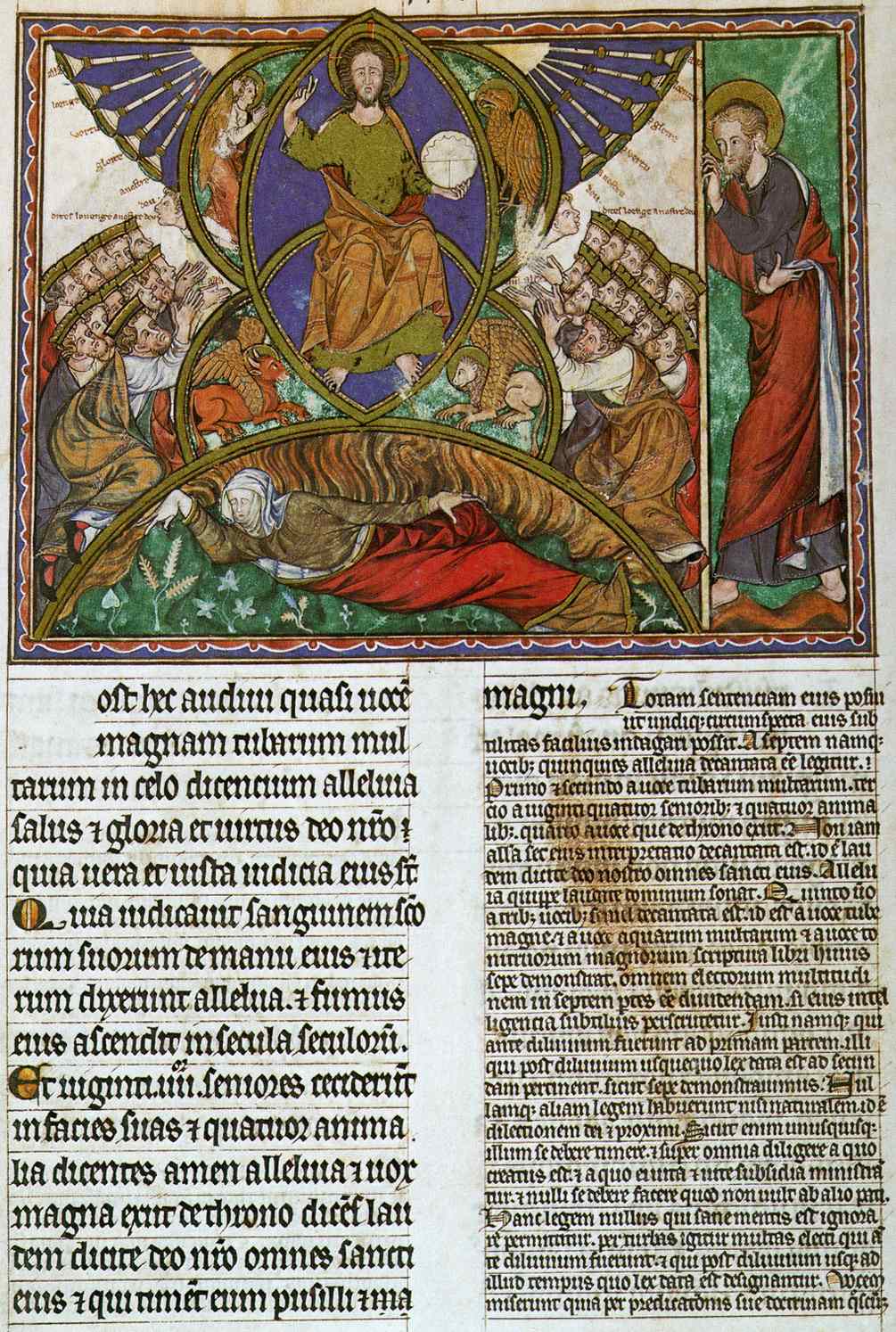

Slide 6: Douce Apocalypse, c. 1270 for Prince Edward, Oxford, Bodleian Library

Slide 7: Westminster Abbey, Sedilia, 1307/08

Slide 8: Psalter of Robert de Lisle, ‘Madonna master’, c. 1310, London, BL

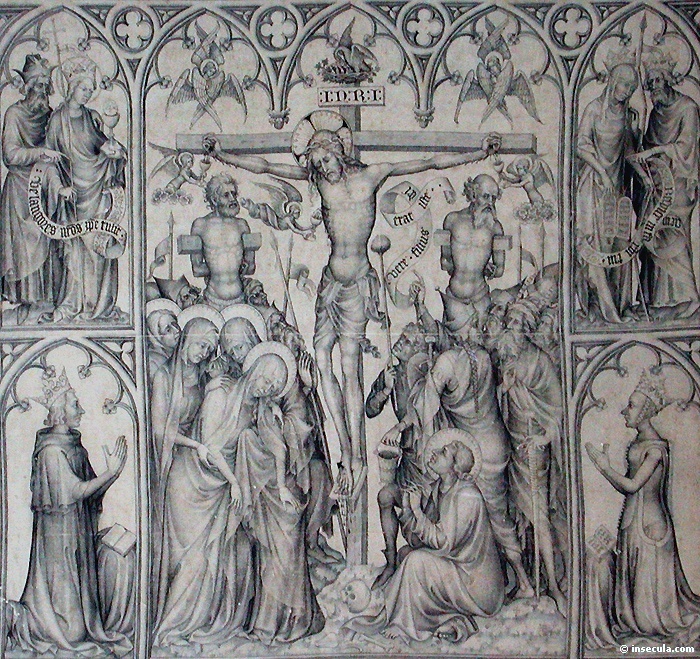

Slide 9: Thornham Parva (Suffolk), Retable, and Frontal in Paris, Musee de Cluny, 1330s

From left: St Dominic, St Catherine, St John the Baptist, St Peter, the Crucifixion,

St Paul, St Edmund, St Margaret, St Peter Martyr.

North and South

Slide 10: Gorleston Psalter, c. 13 10/25, London, BL

Slide 11: Duccio, Maesta, 1308-11

Slide 12: Simone Martini, underdrawing for Salvator fresco, Avignon, cathedral, before 1344

Saviour Blessing (tympanum) and Madonna of Humility (lunette)

1341, Third synopias, Palace of Popes, Avignon

Slide 13: Avignon, papal palace, murals by Matteo Giovanetti and other workshops, 1340s

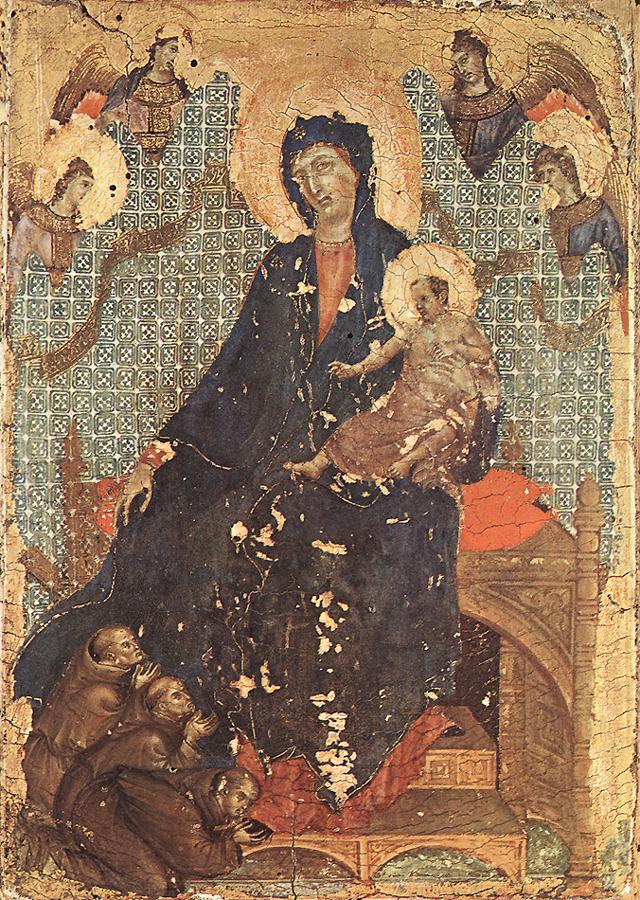

Slide 14: Duccio, Madonna of the Franciscans, c 1295

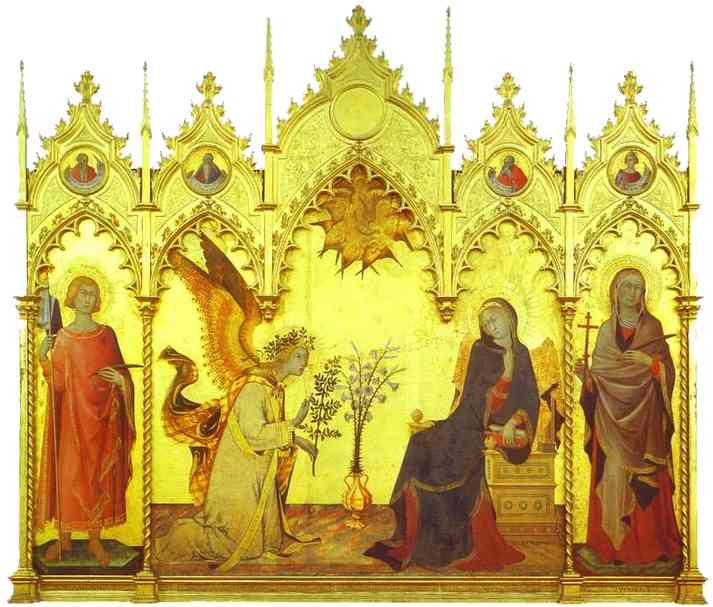

Slide 15: Simone Martini, Annunciation, 1333

Slide 16: Klostemeuburg near Vienna, panels added to Nicholas of Verdun’s ambo, 1331

ambo – a smaller pulpit or platform for reading the Scriptures

Slide 17: Vyssi Brod Altarpiece, c. 1350, Prague, National Gallery

Master of Hohenfurth (or of Vyssi Brod), Bohemian painter (active 1350-70, Prague), so called after his main work, a large altarpiece with scenes from the life of Christ (National Gallery, Prague, c.1350) painted for the monastery of Vyssi Brod (Hohenfurth). These panels show the beginnings of the Bohemian variant of International Gothic. Another important painting from his workship, a Death of the Virgin, is in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Slide 18: Klodzko (Glatz) Madonna for Archbishop Arnost of Pardubice, c. 1345, Berlin, Gemaldegalerie

France and England

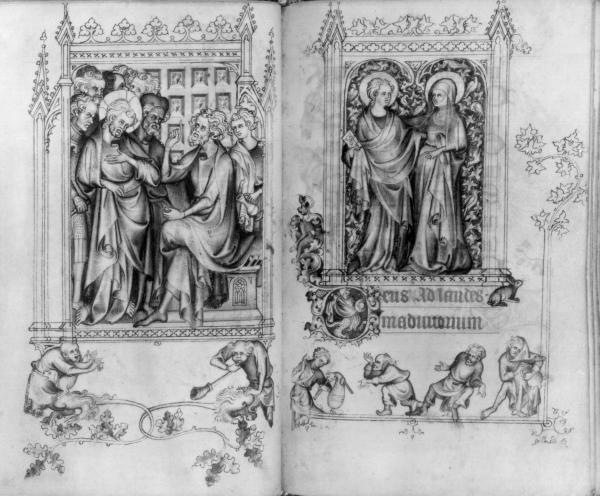

Slide 19: Jean Pucelle (attr.), Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, 1325-8, New York, Met

Slide 20: Portrait of King Jean le Bon of France, c. 1349/64, Paris, Louvre

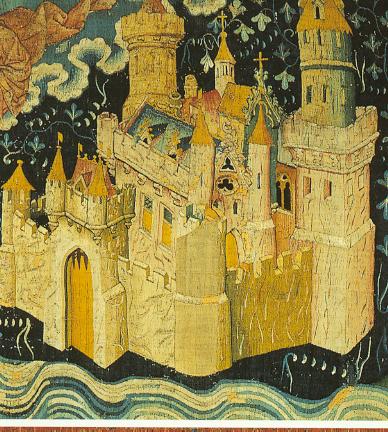

Slide 21: Jean Bondol (design), Angers Apocalyse tapestry for Duke Louis I of Anjou, 1374/81, Angers, Chateau

Slide 22: Parement de Narbonne, c. 1375, Paris, Louvre

Slide 23: Grandes Chroniques de France, c. 1375/80, Paris, BN

King Charles V of France, Emperor Charles IV, and his son King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia. (BNF, FR 2813) fol. 476v , Grandes Chroniques de France, Paris, 14th Century.

(80 x 65 mm)

Slide 24: Grandes heures for Duke Jean of Berry, by Jacquemart de Hesdin and others, c. 1400, Paris, BN

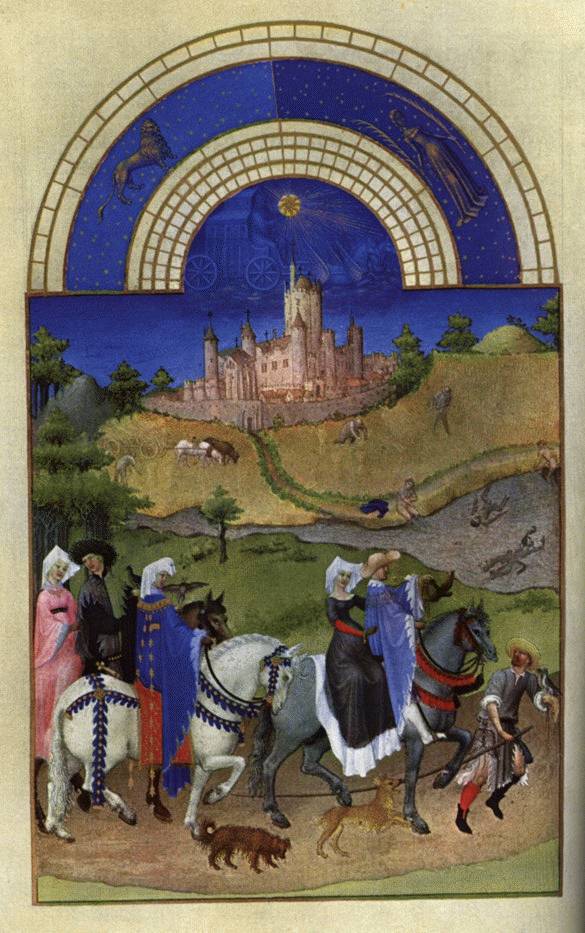

Slide 25: Trés Riches Heures for the Duc de Berry, by Limbourg brothers, begun 1413-16, Chantilly, Musee Conde

AUGUST The month of hawking; the nobles, carrying falcons, are

going hunting while in the background peasants are harvesting

and swimming in the river. Behind them is the Chateau

d’Etampes.

The Tres Riches Heures is the classic example of a medieval book of hours. This was a collection of the text for each liturgical hour of the day – hence the name – which often included other, supplementary, texts. Calendars, prayers, psalms and masses for certain holy days were commonly included.

The pictures in this directory are from the calendar section of the Tres Riches Heures. This was painted some time between 1412 and 1416 and is arguably the most beautiful part of the manuscript; it is certainly the best known, being one of the great art treasures of France. In terms of historical and cultural importance, it is certainly equal to more famous works such as the Mona Lisa, marking the pinnacle of the art of manuscript illumination.

WHO PAINTED THE TRES RICHES HEURES?

The Tres Riches Heures was painted by the Limbourg brothers, Paul, Hermann and Jean. They came from Nimwegen in what is now Flanders but were generally referred to as Germans. Very little is known about them; they are believed to have been born in the late 1370s or 1380s and were born into an artistic family, their father being a wood sculptor and their uncle being an artist working variously for the French Queen and for the Duc de Bourgogne.

They seem to have followed in their uncle’s footsteps and by 1402 had entered into the service of the Duc de Bourgogne as artists. By 1408 they had entered the service of Jean, Duc de Berry, one of the most notable (and richest!) art lovers in France. They are known to have executed several other pieces of work apart from the Tres Riches Heures but most of these, with the major exception of the Tres Belles Heures, seem to have been lost. In around February 1416 all three Limbourg brothers died before the age of thirty, apparently killed by an epidemic.

WHO WAS THEIR PATRON?

Jean de Berry was one of the highest nobles in 15th-century France – his brothers were King Charles V, the Duc d’Anjou and the Duc de Bourgogne, and his nephews were King Charles VI and the Duc d’Orleans. He was inevitably involved in politics as a result of his position and was identified with the Armagnac anti-Burgundian faction, as a result of which his property was attacked on several occasions by pro-Burgundian mobs. (On one such occasion, in 1411, his Chateau de Bicetre was burned to the ground, destroying many of the works of the Limbourgs). In 1416 he died, apparently broken-hearted at the destruction of the French monarchy at Agincourt the previous year.

He was the medieval world’s greatest connoisseur of the visual arts, with a particular fondness for jewels, castles, works of art and exotic animals….

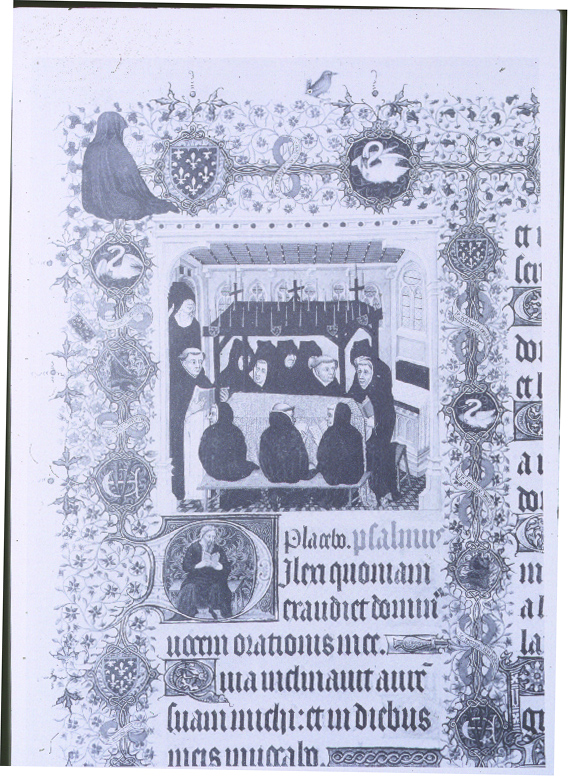

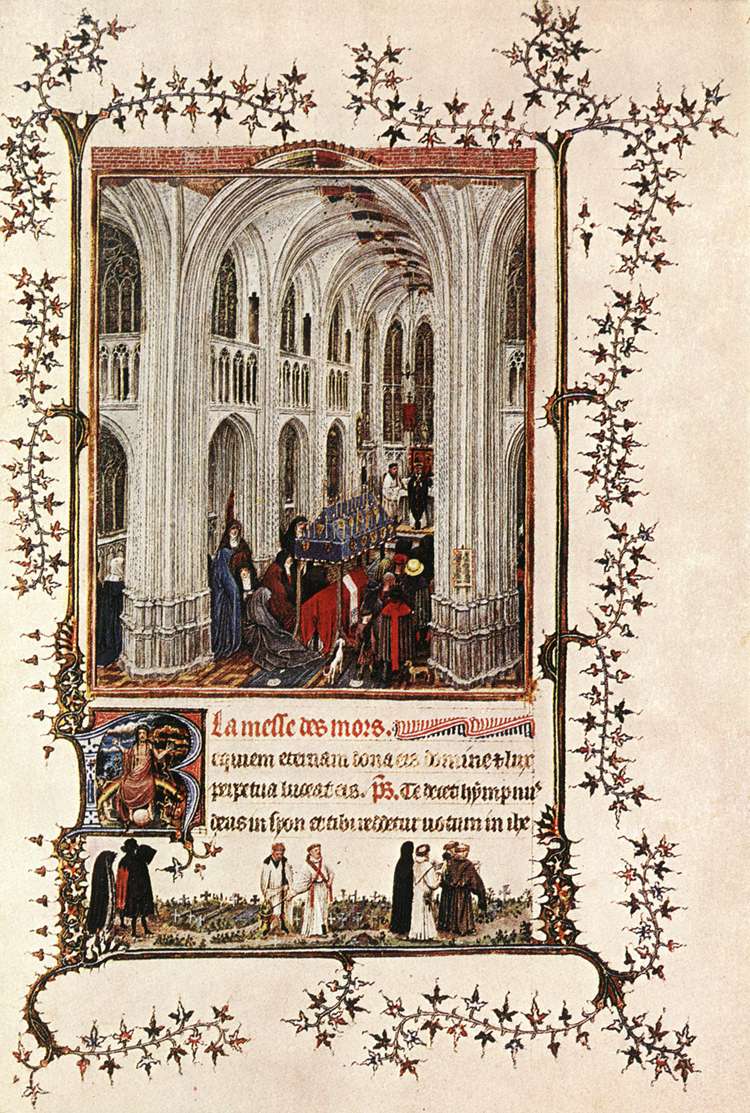

Slide 26: Tres belles Heures/Brussels Hours for the Duc de Berry, by Andre Beauneveu?, Jacquemart de Hesdin and others, begun c. 1390, Brussels, Bibliotheque Royale

Trés Belles Heures of the Duc the Berry (1380-1420) by Netherlandish illuminators

Paris had an organized book trade around its university from the thirteenth century and we must certainly ascribe to Paris many of the best-known Book of Hours of the period of Jean, Duc de Berry. The Tres Belles Heures of the Duc the Berry was began about 1382, it is a Parisian manuscript illuminated mainly by Netherlandish artists. Some illustrations once were attributed to Jan van Eyck by scholars. The manuscirpt combines superb landscapes, accurate, spatially correct interiors, and ornamental borders familiar from the work of Jean Pucelle

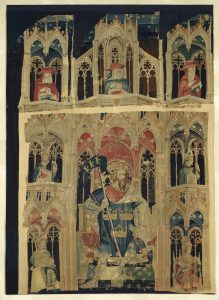

Slide 27: Nine Heroes tapestry, New York, Met

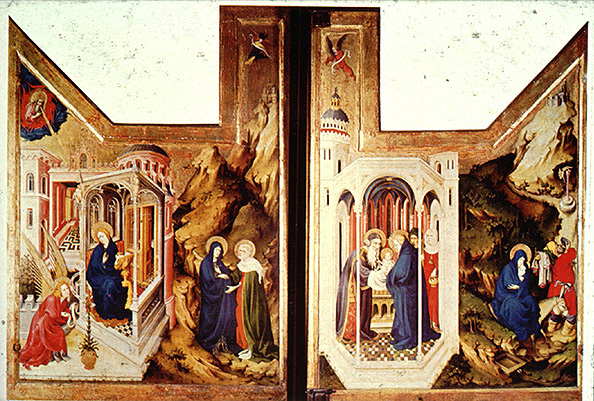

Slide 28: Melchior Broederlam, wings of Champmol Altarpiece, 1394, Dijon, Musee

Melchior Broederlam. Annunciation and Visitation (left); Presentation in the Temple and Flight into Egypt (right), 1394-99.oil on panel. Flemish

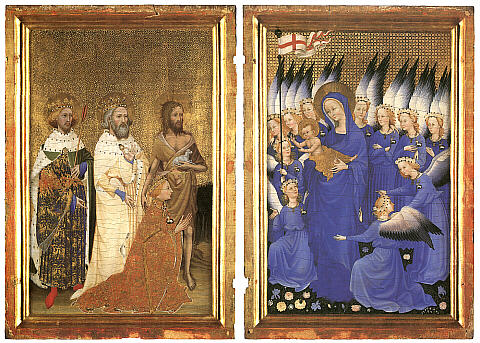

Slide 29: Wilton Diptych, for Richard II of England, 1395/9, London, National Gallery

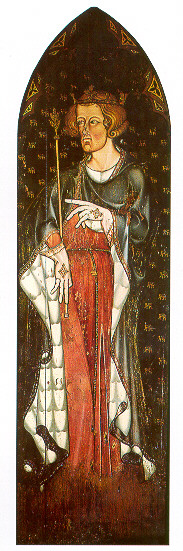

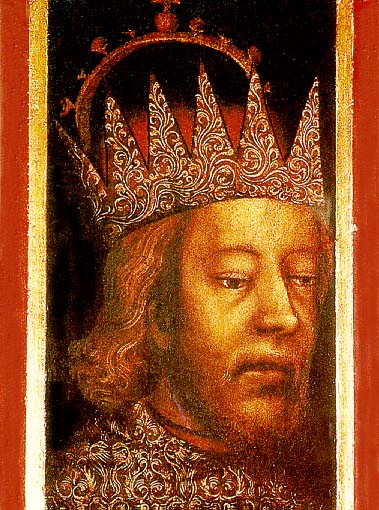

Slide 30: Portrait of Richard II, c. 1390?, Westminster Abbey

Bohemia / the Empire and ‘International Gothic’

Slide 31: Liber Viaticus (portable breviary) of Jan of Streda, c. 1355/64, Prague, Library of National Museum(image not found)

Slide 32: Karlstejn Castle, Luxembourg genealogy (13 55/7; lost); panels and murals in the Holy Rood Chapel by Master Theodoric (c. 1360/5) and Tommaso di Modena(image not found)

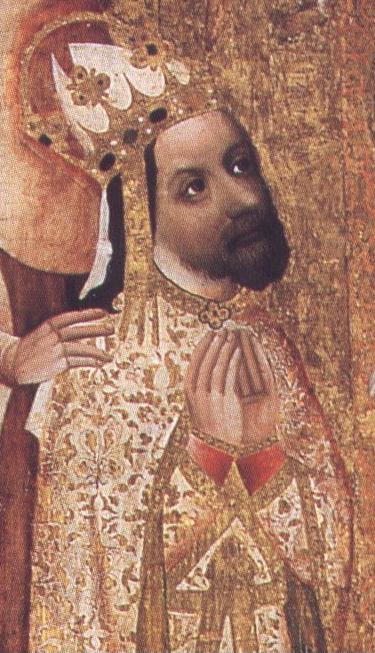

Slide 33: Votive Panel of archbishop Jan Ocko for Roudnice palace chapel, 1371, Prague, National Gallery

Slide 34: Portrait of Archduke Rudolf IV of Austria, 1358/65, Vienna, Diocesan Museum

Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria+Steiermark 1339-1365 (son of Albrecht II, Duke of Austria and Johanna of Pfirt)

Slide 35: Schloss Tirol Altarpiece, 13 75/86, Innsbruck, Landesmuseum

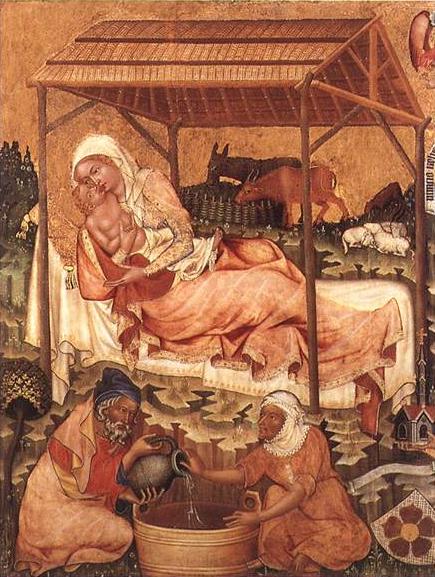

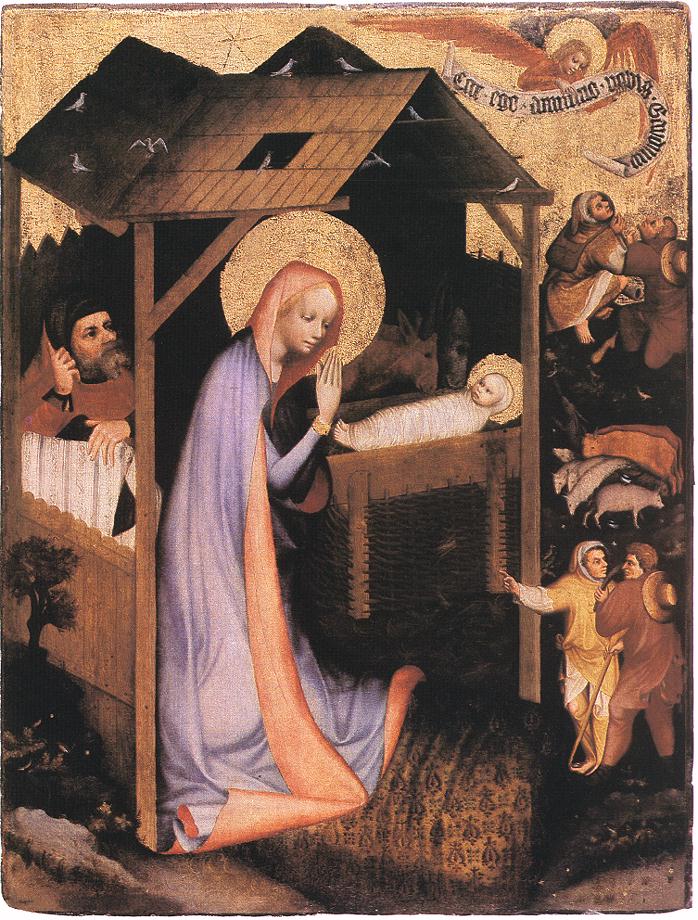

Slide 36: Trebon Altarpiece, 1380s, Prague, National Gallery

MASTER of the Trebon Altarpiece, Bohemian painter (active in 1380-1400)

The Adoration of Jesus, before 1380, tempera on spruce, 127 X 96.3 cm

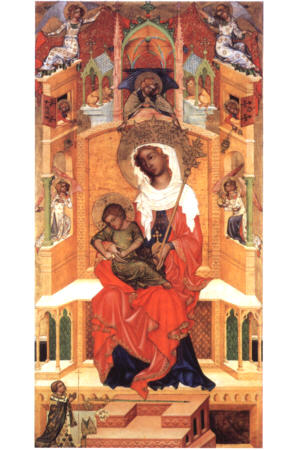

Slide 37: St Vitus Virgin, c. 1400, Prague, National Gallery

Unknown master, The Madonna of St Vitus Cathedral in Prague, c. 1420, tempera on wood, 89 x 77 cm, National Gallery, Prague

The half length figure of the Virgin holding her Child in front of her on her right side appears in an ornate, three-dimensional frame – though we are not sure whether the frame originally belonged to the picture.

Although the whole composition and the manner in which Mary is showing her Child to the congregation of the faithful has preserved the formal solemnity of devotional pictures, the almost coquettish posture of her head and the animation of the Child radiate a natural atmosphere.

The striking three-dimensional qualities of the painting point to the influence of the sculptures of “Beautiful Madonnas” of the period, indeed, some scholars believe that the painter is identical with the master of the Beautiful Madonna of Krumlov. Precise and subtle modelling conveys the full forms of the figures, as do the deep, falling folds of the Virgin’s mantle, which is made of some heavy fabric; the Child’s body and hands are represented organically, and the two figures constitute a group imagined in spatial terms. The Virgin is depicted in a complicate counterpoise: her body is not only bent sidewise, but is also drawn backwards, whereas the whole torso of Jesus faces the spectator. The movements of the two figures in opposite directions stress that the construction of the composition is determined by the two diagonals of the oblong standing frame. The torso of the Virgin is bent into the direction of the diagonal line directed towards the upper right corner, while her head and the Child’s body parallel with it point to the opposite direction. The two flesh-coloured areas, the face and the body, are placed in the middle of that diagonal line. The harmonious overall effect of the well-poised composition is intensified by the fact that the Infant’s right shoulder is merged with that of His mother and by this means a single, undisturbed outline encloses the two figures.

Slide 38: Bible of Wenceslas IV, begun l380s?, Vienna, Austrian National Library

Slide 39: Westminster Abbey, Liber Regalis, begun 13 80s?

Slide 40: Trent, Castel del Buonconsiglio, murals in Torre Aquile, by Master Wenceslas?, c. 1400

03/03/02005 Andrea Putz