Canterbury Cathedral, stained glass

Canterbury Cathedral stained glass 13thC

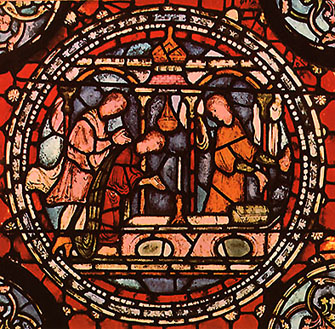

From the Corona, this 13th-century glass shows pilgrims praying at the old shrine of St. Thomas in the crypt, before his relics were translated to the much more opulent shrine in the Trinity Chapel (1220).

;

Two events occurring in 1170 and 1174 laid the foundations of what today is regarded as one of the most important stained glass collections of the late 12th century in the world. The murder of Thomas Becket, as despicable as it was, provided the Cathedral with a powerful attraction to pilgrims, who came to Canterbury in enormous numbers to make offerings. When disaster struck again with the destruction by fire of the Romanesque Quire in September 1174, it was the proceeds from this lucrative pilgrim trade that enabled the monks to build the new Quire and the Trinity Chapel and to fill it with stained glass of outstanding splendour. The fact that, unusually, the Canterbury monks did have a steady income at their disposal resulted in the creation of a building of unprecedented scale and complexity which was completed in a remarkably short period of time. The glazing scheme was conceived in close co-operation between the master builder, glazier and the monks. By 1176, the complete programme was determined and brought to life within 44 years by workshops of English and French craftsmen. The scheme is thus unusually homogenous in its planning and execution, reflecting also its close integration in the overall concept of the eastern arm of the church which was to serve two distinct categories of worshipper, the monks and the pilgrims. The medieval Cathedral was part of a priory, and in the body of the Quire the monks observed the daily routine of the monastic office. The windows of this part are therefore of a very different character from those in the Trinity Chapel which served the pilgrims for their devotions at St. Thomas’ shrine. Besides numerous windows in side chapels, the glazing scheme for this reason consists of three major series, one for the Quire and one for the Trinity Chapel respectively, and the third on clerestory level linking both parts of the building together again. In the Quire aisles, a biblical emphasis prevailed. Here the mediaeval monks could study the twelve windows from both Old and New Testaments, arranged to demonstrate the way in which events of the Old Testament were thought to prefigure events in the New. This typological interpretation is based on one of the most popular mediaeval books, the Biblia Pauperum or ‘Poor Man’s Bible’. The two surviving windows of this series in the north Quire aisle give a striking insight in the mediaeval way of interpreting the world. For the pilgrims visiting St. Thomas’ shrine, a different subject matter was requested. The twelve windows of the Trinity Chapel therefore illustrated two detailed accounts of Becket’s life and the miracles that had taken place at his tomb between 1171 and 1173. Called the Miracle Windows, the stories chosen show the full gamut of medieval society receiving comfort and aid from St. Thomas’ intercession. The richly coloured glass would for many pilgrims be the finest thing they would ever see, a fitting prelude to the shrine itself. Finally, in the clerestory, the so-called Genealogical Series depicts paired figures, beginning on the north side with the Creation and Adam and culminating on the south side with the Virgin Mary and Christ. With 86 figures taken from the gospel of Luke, this genealogy of ancestors of Christ is the largest of its kind in art. Only 48 figures, however, have survived, some now relocated in the south west transept and the west window and replaced with nineteenth century copies in their stead. Although the scheme has suffered over the centuries from many forms of destruction, the late 12th century glazing at Canterbury has today established its firm place as the most complete collection of its kind in England. The glazing of the western parts was less fortunate. The whole scheme of nave windows has been almost completely swept away, with only the two great windows in the west wall and in the north west transept surviving. Both these windows are associated with kings, Richard II and Edward IV, and although in particular the ‘Royal Window’ of 1485 in the north west transept had suffered from the notorious attack by Culmer in the 1640’s, there is a substantial amount of glass left to tell of the superb quality of 14th and 15th century draftmanship and glazing skills. ‘