49-01 Bauhaus

A typical Bauhaus inspired room:

An interesting discussion about the Bauhaus based on my notes and other sources

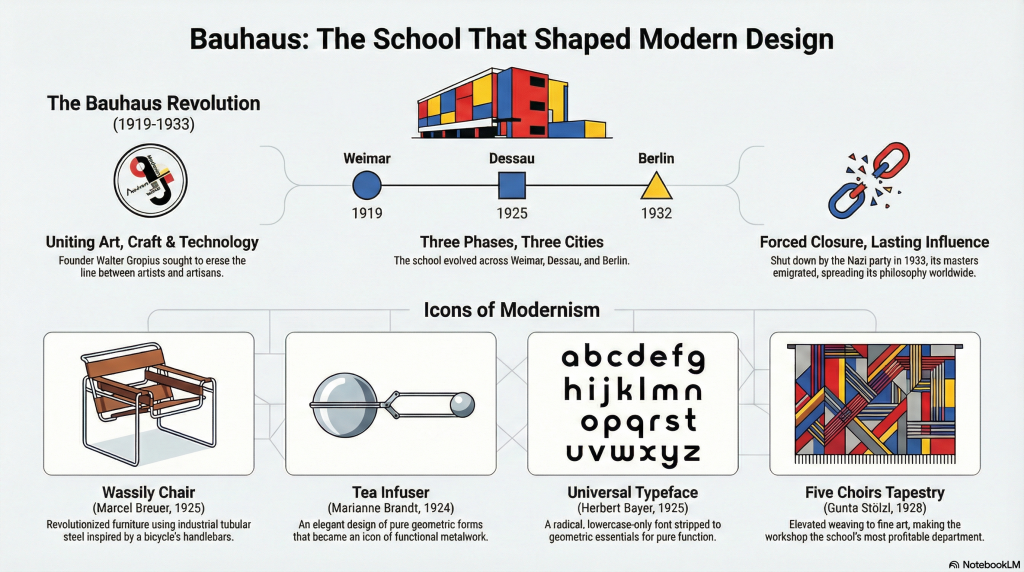

We live within the architectural echoes of a ghost. You see it in the shimmering, curtain-walled monoliths of our city centers, the geometric precision of the sans-serif fonts on your smartphone, and the skeletal steel frames of your office furniture. This ubiquitous aesthetic—the visual DNA of the 21st century—was forged in a radical institution that existed for a mere fourteen years. Between its founding in 1919 and its forced dissolution in 1933, the Bauhaus migrated across three German cities (Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin), surviving on a razor’s edge of political vitriol and financial instability. It remains the great paradox of design history: a school that lasted barely a decade, yet managed to dismantle centuries of ornate tradition to invent the modern world. We inhabit a “Bauhaus world” so completely that we have become blind to its radicalism, forgetting that our “less is more” reality was once a revolutionary battle cry.

1. The Alphabet Without Capitals: Why We Don’t “Speak” in Uppercase

In 1925, Herbert Bayer, the youngest master at the school, performed a linguistic surgery that still dictates our digital interfaces. He designed the “Universal Typeface,” a font that distilled letters into their geometric essentials—circles, arcs, and straight lines—and, most subversively, eliminated capital letters entirely.

This was not merely a stylistic exercise in “material honesty”; it was a calculated political assault. In the wreckage of post-war Germany, capital letters represented the rigid hierarchy and imperial authority that the modernists blamed for the continent’s collapse. Bayer argued that a dual alphabet was an irrational vestige of the past, an unnecessary complexity that hindered the efficiency of the “complete building” Gropius envisioned.

“Why should we write and print with two alphabets? We do not speak in capitals.”

While the “lowercase-only” movement never fully conquered the world, Bayer’s approach provided the blueprint for the typographic clarity we demand today. If you find the geometric purity of a font like Futura (released in 1927) or the cleanliness of a modern app interface pleasing, you are standing in the shadow of Bayer’s 1925 rebellion against the uppercase.

2. The “Wassily” Chair: A Marketing Myth Born from a Bicycle

The Model B3 chair is arguably the most recognizable silhouette in the history of furniture. We know it as the “Wassily” chair, but that name is a marketing fiction concocted by manufacturers decades later to capitalize on the prestige of painter Wassily Kandinsky. While the Russian master did own an early version, the chair was actually the brainchild of a twenty-three-year-old Hungarian student named Marcel Breuer.

The inspiration was delightfully prosaic: the curved handlebars of an Adler bicycle. Breuer realized that if industrial tubular steel could support a cyclist, it could be bent to support a body in a living room. At the time, using “factory” steel for home furniture was a profound scandal. Traditionalists, who valued heavy, hand-carved wood, were horrified by a chair that appeared to be a transparent skeleton of metal and stretched fabric.

The ultimate irony lies in its valuation. In 1925, Breuer intended the B3 to be a tool for the masses, costing approximately 40 marks—an affordable piece for the German middle class. Today, a licensed version functions as a high-end status symbol, commanding between $2,000 and $3,000. The “industrial tool” has been elevated to an elite trophy, a transformation that would likely have baffled its young inventor.

3. The Profitable “Women’s Ghetto”: Turning Relegation into Triumph

The Bauhaus famously declared a progressive mission to erase the distinction between fine art and craft, yet it harbored its own internal glass ceilings. Despite the school’s egalitarian manifesto, female students were systematically steered away from “masculine” workshops like metal or glass and funneled into the weaving workshop—a department faculty dismissively referred to as the “women’s ghetto.”

Gunta Stölzl, who joined in 1919, transformed this restriction into the school’s financial engine. By applying the cerebral color theories of Klee and Kandinsky to industrial textiles, she turned weaving into the school’s most profitable department. Stölzl was a technical pioneer, mixing natural wool and cotton with artificial silk and metallic threads to create textiles that functioned as acoustic panels and light-reflecting room dividers.

In 1927, she became the weaving workshop’s master—the only female master in the school’s history. Despite her success, she was denounced by conservative students as a “cultural Bolshevik” and her work remained largely unknown for decades after her forced resignation in 1931. The department meant to sideline women was the very one that saved the school from bankruptcy.

4. The High Cost of “Mass Production”: The Tea Infuser Paradox

Marianne Brandt’s 1924 Tea Infuser is a masterclass in Bauhaus geometry: a hemisphere of silver balanced on a cross-shaped base with an ebony handle. Brandt was one of the few women admitted to the metal workshop, where she was initially hazed by Master László Moholy-Nagy and male students with brutal tasks like hammering metal sheets for hours. She endured, and by 1928, she became the first woman to lead the metal workshop.

Brandt’s work embodied the Gropius pivot toward “art and technology—a new unity.” Her infuser featured a non-drip spout and was designed to balance perfectly during pouring. However, it highlights the friction between Bauhaus ideals and economic reality.

“My guiding principle was to design objects which fulfil their purpose perfectly.”

While Brandt designed the piece for mass production, its complex geometry required such highly skilled silversmithing that it could never be produced cheaply for the everyman. Instead of an affordable industrial tool, it became an expensive luxury item—a beautiful “failure” of the school’s mission to democratize design.

5. Spiritual Chaos vs. Industrial Logic: The Battle for the School’s Soul

The Bauhaus was never a monolith; it was a site of constant intellectual warfare. In its early Weimar years, the school was defined by a monk-like mysticism. Master Johannes Itten led the preliminary course with breathing exercises, meditation, and students dressed in robes.

This spiritualism was eventually purged in 1923 when Walter Gropius pivoted toward rationalism, replacing Itten with László Moholy-Nagy, who viewed art as a laboratory experiment involving photography and film. Even among the painters, the clash was palpable. Wassily Kandinsky codified “objective truths” in color—believing Yellow was earthly energy and Blue was spiritual transcendence.

These theories were mocked by later masters like Josef Albers. A 32-year-old former primary school teacher when he arrived, Albers preferred working with “found bottle shards” arranged in grids over Kandinsky’s cosmic “nonsense.” This shift from the “spiritual soul” to the “industrial mind” defined the school’s maturity.

6. The Living Sculptures: When Dancers Became Geometry

Perhaps the most surreal expression of the Bauhaus was Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet (1922). Schlemmer sought to explore space mathematically, transforming human dancers into “living sculptures” through costumes made of spheres, cones, and cylinders of padded cloth and papier-mâché.

The costumes were deliberately designed to restrict movement, forcing the dancers to abandon natural gestures in favor of a non-natural, mathematical choreography. They became geometric puppets tracing paths across a grid. For the modern audience, this “mathematical movement” remains a startlingly relevant commentary on our own interactions with the world. Just as Schlemmer’s dancers had to adapt their bodies to the restrictive geometry of their costumes, we now find ourselves constantly adjusting our natural human behaviors to fit the rigid, mathematical interfaces of our digital lives.

Conclusion: A Legacy That Couldn’t Be Closed

When the Nazi party finally forced the permanent closure of the Bauhaus in Berlin in 1933, they intended to extinguish its “degenerate” influence. They achieved the exact opposite. By closing the school, they acted as a centrifugal force, scattering its masters—Gropius, Breuer, Albers, and Mies van der Rohe—across the globe. These designers fled to England and America, taking Bauhaus principles to Harvard, Yale, and the Chicago skyline.

The Bauhaus was born from the “collapse of an empire,” emerging from the ruins of post-WWI Germany to find order in geometry. It leaves us with a compelling question: If such a short-lived institution could reinvent the visual language of the world out of the chaos of the early 20th century, what kind of radical design might emerge from the fractures of our own era?