48-01 Piet Mondrian and De Stijl

My notes on Piet Mondrian and De Stijl

A discussion of Piet Mondrian and De Stijl based on my notes and other sources

We move through our daily lives assuming we understand the systems that surround us—the classrooms where we learn, the clinics where we seek care, and the very chairs where we rest. We treat these as functional backdrops, rarely pausing to consider the deliberate philosophies or psychological undercurrents that dictate their design. However, the reality of our social and aesthetic structures is often far more complex and more intentional than it appears on the surface.

From the high-pressure internal lives of “gifted” students to the radical spiritualism of 20th-century art, our world is shaped by a constant tension between the individual and the universal. To truly understand the modern landscape, we must look past the “natural appearance” of things and examine the blueprints beneath. Here are five counter-intuitive truths about the hidden structures of the way we live.

- The Honors Student Anxiety Paradox

In the halls of academia, the “Honors” label is often viewed as a golden ticket—a predictor of success and a signifier of prestige. However, research into student psychology suggests that this distinction may be a double-edged sword. According to the “Asset or Obstacle” hypothesis proposed by researcher Sarah Pelfrey, there is a distinct cognitive split in how high-achieving students experience stress.

Using diagnostic tools like the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and the Big Five Inventory, Pelfrey’s research highlights a fascinating paradox: Honors students often possess higher “trait anxiety”—a baseline, personality-driven pressure to perform—but exhibit lower “state anxiety” during traditionally stressful events like examinations. While their status as “gifted” provides them with an academic asset, the underlying personality traits that drive them to maintain that prestige can become a lifelong burden.

“Can this distinction, which is traditionally looked upon with such appeal, actually be detrimental to the student?” - To Find Universal Truth, You Must First “Destroy” Reality

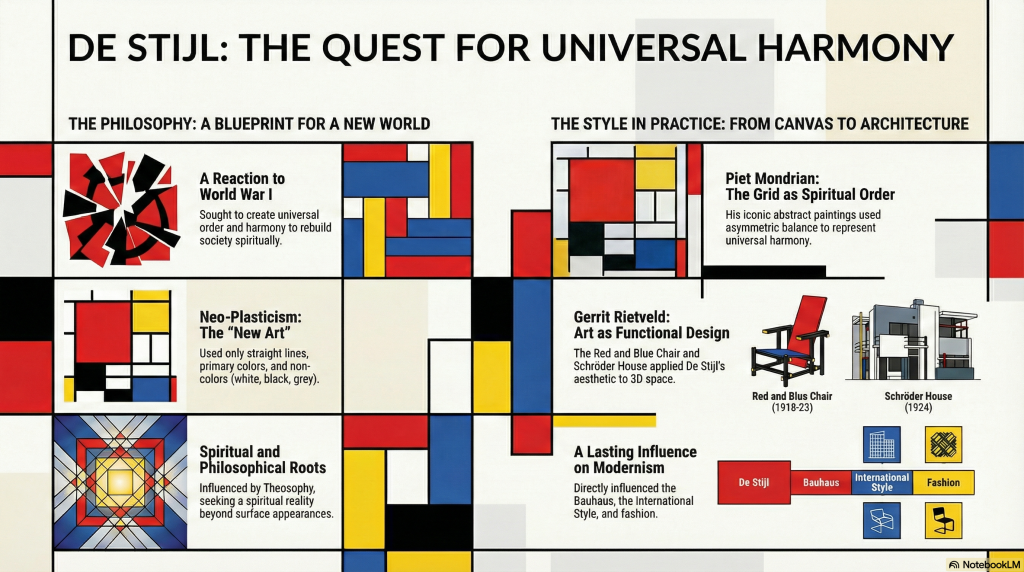

When we look at a painting by Piet Mondrian—a grid of black lines and primary colors—it can feel like a retreat into a void. In reality, it was a “spiritualized world order” born from the literal devastation of World War I. Mondrian, a lifelong member of the Theosophical Society, believed that art should act as a bridge to a divine principle. To reach this higher reality, he felt he had to “destroy” natural appearance.

This philosophy, known as Nieuwe Beelding (New Design) or Neoplasticism, sought to reach the “immutable core” of the universe by stripping away the “normal domain of the senses.” Mondrian even equated the “destruction of melody” in music with the destruction of natural form in art; because melody represents a sequence in time and nature, it had to be dismantled to reveal a timeless, spiritual harmony found in the duality of horizontal and vertical lines.

“True Boogie-Woogie I conceive as homogeneous in intention with mine in painting: destruction of melody which is the equivalent of destruction of natural appearance…” - The Gap Between Needing Help and Seeking It

In low-income urban areas, such as South Dallas, the barrier to healthcare is rarely just a lack of physical clinics. Insights from researchers Grace McNair and Barrett Corey, combined with the “Urban Churches” study by Julie Johnson et al., reveal a profound disconnect between institutional perception and individual reality.

While urban church leaders in Dallas often perceive their social outreach and charity as highly effective in promoting justice, the individuals they aim to serve often face a “perception gap.” An individual’s past interactions and their awareness of the system are more predictive of health outcomes than the proximity of a hospital. When the institution’s self-perception of effectiveness doesn’t account for the individual’s perception of the system as inaccessible or confusing, a barrier remains that no amount of infrastructure can fix. - Sitting for the Spirit, Not the Flesh

Gerrit Rietveld’s “Red and Blue Chair” is a landmark of modern design that famously rejects physical comfort. This was a radical choice. Rietveld, an early member of the De Stijl movement, originally produced the chair in 1918 without color; it was only in 1923 that he applied the iconic primary palette to emphasize its “manmade” quality over the hand-craftsmanship of the past.

Rietveld’s furniture was designed as a spatial object that allowed space to flow through it uninterrupted. By using standard lumber sizes, he favored mass production over elitist convenience. The goal was to design for the “seated spirit” rather than the “seated flesh,” creating a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) that forced the user to remain conscious and disciplined within their environment.

“When I sit, I do not want to sit as my seated flesh likes, but rather as my seated spirit would sit, if it wove the chair for itself.” - The “Dynamic Diagonal” That Broke an Art Movement

We often think of art movements as cohesive groups, but De Stijl was a “virtual assemblage” of artists who largely communicated by letter—Mondrian and Rietveld, in fact, never even met in person. This movement was ultimately undone by a single 45-degree angle. While Mondrian insisted on the stability of horizontal and vertical lines to represent universal order, Theo van Doesburg introduced a heresy known as “Elementarism.”

Van Doesburg began utilizing the diagonal line to represent “dynamism” and “continuous development.” To Mondrian, the diagonal was a betrayal of the spiritual balance they had spent years refining. This technical schism over the 45-degree angle was so profound that Mondrian seceded from the group, leading to the collapse of the collective project. It is a striking example of how a tiny technical choice can dismantle an entire utopian vision.

Conclusion: The Living Masterpiece

The radical ideas of the early 20th century eventually “dissolved” into the fabric of modern life. We see their fingerprints in the functionalist architecture of the Bauhaus and the “Mondrian” cocktail dresses of Yves Saint Laurent’s 1965 collection—which served as a “test of simplicity,” featuring complex seams invisible to the naked eye to maintain the purity of the grid.

These structures, from our academic honors programs to our minimalist digital interfaces, continue to challenge the tension between the individual and the universal. They promise harmony and order, but they often demand the “destruction” of our personal naturalness or physical convenience to achieve it. As we inhabit these modern systems, we must ask ourselves which part of us is being prioritized: our bodies, or our spirits?