Page Contents

46-01 Dada

An entertaining discussion about Dada produced by NotebookLM from my notes

Have you ever stood in a modern art museum, stared at a seemingly random collection of objects, and thought, “What am I even looking at?” It’s a common experience. The path from classical painting to contemporary installation is filled with bizarre turns and intentional disruptions. One of the most significant and purposefully chaotic of these disruptions was an international movement born from the rubble of a world at war: Dada.

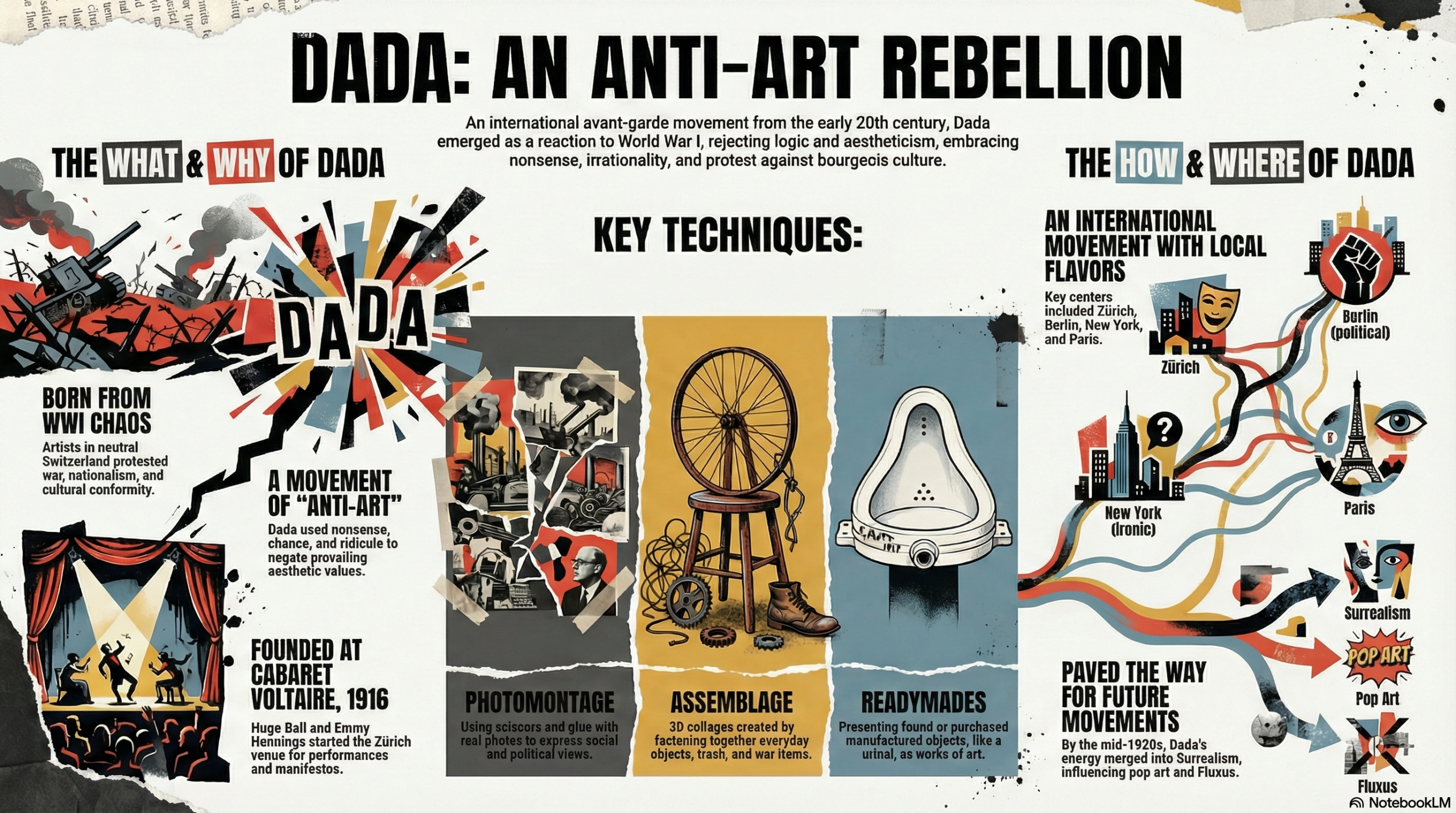

Emerging from the trauma and absurdity of World War I, Dada was more than an art style; it was an “anti-art” rebellion. Its artists used nonsense, chance, and ridicule to protest the logic, nationalism, and bourgeois culture they believed had led millions to their deaths in the trenches. They wanted to tear down the entire temple of Western art and culture, which they felt had failed humanity.

But beneath the surface of chaos, Dada was a sophisticated, witty, and profoundly influential movement. This article will explore five of the most surprising and impactful ideas behind the rebellion, revealing a calculated response to a mad world that staged a permanent rupture in the very definition of art.

1. The Most Influential Modern Artwork Was a Urinal.

In 1917, the artist Marcel Duchamp did something that still echoes through the art world. He walked into the showroom of J.L. Mott Iron Works, purchased a standard porcelain urinal, brought it to his studio, turned it on its back, signed it “R. Mutt 1917,” and submitted it to an art exhibition. He titled it Fountain.

The exhibition, organized by the Society of Independent Artists, was founded on the principle that it would accept and display every single work submitted. Duchamp’s piece, however, was quietly rejected by the board, who refused to believe it was art. The original was soon lost, most likely thrown out as rubbish.

This was not merely a prank; it was a deliberate act of contempt for a high-art tradition that felt hollow and complicit in cultural decay. With this simple, provocative gesture, Duchamp introduced the concept of the “readymade”—an ordinary, manufactured object that the artist selects and presents as art. It was a direct assault on centuries of tradition, which prized technical skill, beauty, and originality. Duchamp argued that the artist’s idea was more important than the physical craft.

The surprising legacy of this defiant act? In a 2004 survey, 500 of Britain’s most influential art figures voted Fountain the “most important artwork of the twentieth century.” It is so impactful because it permanently changed the rules. Art was no longer just about what an artist could make with their hands; it was about what an artist could make us think.

2. Their “Nonsense” Followed Surprisingly Strict Rules.

While Dada appears to be the epitome of random chaos, its artists were fascinated with using rigid systems to create their work. The goal was often to remove their own personal taste from the process in a direct protest against the romantic notion of the artistic “genius” whose grand visions had led Europe to slaughter.

The poet Tristan Tzara, a key figure of the movement, famously published a set of instructions for creating a Dadaist poem. The process is a perfect example of this systematic approach to nonsense:

Take a newspaper.

Take a pair of scissors.

Choose an article.

Cut out the article.

Cut out each word and put them in a bag.

Shake the bag gently.

Pull out the words one by one and copy them down.

Similarly, the artist Jean Arp created his work Collage with Squares Arranged According to the Laws of Chance by tearing colored paper into squares, dropping them onto a backing sheet, and gluing them down. But the revolutionary method was not entirely random. Arp used chance as a starting point, but then arranged the fallen squares with careful attention to visual balance, exploring the tension between accident and intention, chaos and order. This radical philosophy suggested that art could be generated by a system, by the universe itself, thereby undermining the artist’s ego.

3. It All Started as a Protest in a Nightclub.

The birthplace of Dada was not a pristine art gallery or a quiet studio, but a raucous nightclub in Zurich called the Cabaret Voltaire. Founded in 1916 by poet Hugo Ball and performer Emmy Hennings, it became the epicenter of the movement.

During World War I, Switzerland was a neutral haven. Artists, writers, and intellectuals from across Europe fled there to escape the war. At the Cabaret Voltaire, they channeled their disgust with the conflict into experimental performances. Nights at the cabaret were filled with cacophony: simultaneous poems were read aloud in different languages, a “balalaika orchestra” played folk songs, and Ball himself performed “sound poems”—meaningless syllables designed to liberate language from its conventional use. For one performance of his poem “Karawane,” he wore an enormous cardboard costume constructed like a bishop’s vestments and was so constrained by it that he had to be carried on stage.

This was not just avant-garde entertainment; it was a furious protest. The artists blamed rationalism, nationalism, and bourgeois society for the carnage of the war. They used absurdity to fight absurdity. As artist Marcel Janco later recalled:

We had lost confidence in our culture. Everything had to be demolished. We would begin again after the tabula rasa. At the Cabaret Voltaire we began by shocking common sense, public opinion, education, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order.

4. The Artists Saw Themselves as “Engineers,” Not Romantics.

The Berlin Dadaists, who were more overtly political than their Zurich counterparts, aggressively rejected the traditional image of the soul-searching artist. Witnessing a world being assembled and disassembled by the machines of war and industry, they adopted a new persona: “monteurs,” a German word for mechanics or engineers.

Their primary technique was photomontage. Using scissors and glue instead of paintbrushes, they constructed caustic visual critiques from the fragmented, mass-produced reality of modern life. They cut up photographs and text from magazines and newspapers, assembling them into cacophonous collisions of mass-media imagery.

A key example is Raoul Hausmann’s assemblage Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Age). The work is a hairdresser’s wooden dummy—a hollow, commodified object—adorned with various items: a tape measure, a wallet, parts of a typewriter, a pocket watch mechanism, a metal cup, and a jewellery box. The title is deeply ironic. Hausmann’s “spirit of the age” is a critique of the modern individual, whom he saw as an empty-headed automaton, controlled by external, mechanical forces with no independent spirit.

5. It Wielded a Powerful, Early Feminist Critique.

Among the most insightful of the Berlin Dadaists was Hannah Höch, the only woman to exhibit at the landmark First International Dada Fair in 1920. She used the movement’s techniques to craft a sophisticated and cutting feminist critique of post-war German society.

Her masterpiece is the monumental photomontage, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany. The title itself is a manifesto. Höch wields the “kitchen knife”—a domestic tool associated with women’s work—to slice through the bloated, masculine, “beer-belly” political establishment of the Weimar Republic.

The collage is a dizzying collision of images. In one section, Höch lampoons military authority by placing General von Hindenburg’s head on the body of a belly dancer, mocking the machismo of the old Prussian order. Elsewhere, she juxtaposes the heads of establishment politicians with the bodies of dancers. In a powerful act of self-insertion, she places a small photograph of her own head on a map showing the European countries where women had finally gained the right to vote. Her work was a brilliant feminist intervention, using the Dada language of chaos to challenge the patriarchal structures of both the German government and the often male-dominated avant-garde itself.

A World Gone Mad

Dada was far more than an outburst of nihilistic nonsense. It was a calculated, witty, and deeply profound response to the trauma of World War I and the anxieties of an emerging machine age. Through urinals, chance-based poems, nightclub protests, and political photomontages, its artists waged a war on convention. They shattered the old definitions of art to make way for the new.

The movement’s greatest legacy is the questions it dared to ask: What is art? Who gets to decide? And what is its purpose in a world that seems to have lost its mind? These are the same questions that artists, critics, and audiences are still grappling with a century later. In an age of digital chaos and political absurdity, what would a 21st-century Dada rebellion look like?

46-02 Marcel Duchamp

An entertaining discussion about Marcel Duchamp produced by NotebookLM from my notes

Five Surprising Lessons from Marcel Duchamp

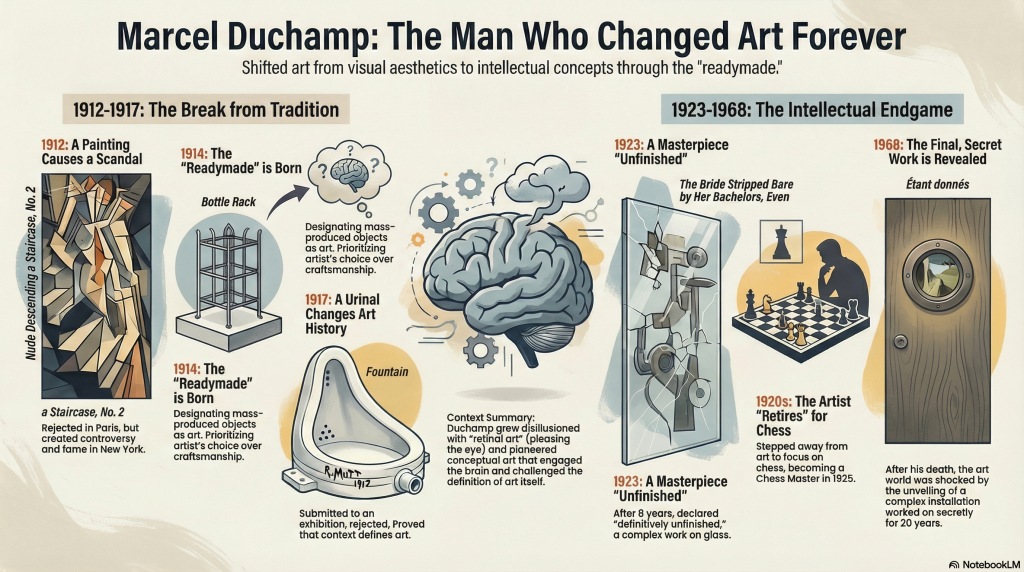

Marcel Duchamp is the art world’s ultimate Trojan Horse. He is the most influential figure of the 20th century, yet he achieved this status by systematically dismantling the “cult of the brushstroke” and refusing to make “art” in any traditional sense.

While his contemporaries were drowning in color and composition, Duchamp simply walked away at the height of his fame. He traded the canvas for the chessboard and the studio for a librarian’s desk. This wasn’t a failure of ambition; it was a strike against the hollow aesthetics of his time.

By examining his counter-intuitive choices, we find a new definition of creativity that prioritizes the “intellectual gray matter” over mere visual pleasure. Here are five surprising lessons from the man who broke art so he could finally save it.

Lesson 1: The “Retinal Art” Rebellion: Why Looking Isn’t Thinking

Duchamp’s early career was a flirtation with the “retinal trap” of Impressionism and Cubism, but he quickly grew bored with art intended only to please the eye. He viewed the obsession with aesthetic beauty as a shallow pursuit that ignored the brain’s potential.

He demanded that art move away from the physical surface and toward a conceptual engagement. To Duchamp, the idea was the masterpiece, and the object was merely its vessel. He effectively signaled the end of the artist as a mere craftsman of the “pretty.”

Duchamp early work was Impressionist and he later distanced himself from what he called ‘retinal art’, that is eye that pleases the art. He wanted art to engage the brain.

Lesson 2: The Scandalous Power of a Wrong Title

In 1912, Duchamp completed Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, a mechanical study of motion that would be his final major canvas. It was first rejected by the Cubist establishment—including his own brothers—who found the title “too literary” and the style “too Futurist.”

Duchamp was furious at this censorship by his peers and immediately withdrew the work. The real explosion happened at the 1913 Armory Show in New York, where American critics, baffled by the geometric fragmentation, turned the painting into a national scandal.

- One reviewer famously dismissed it as “an explosion in a shingle factory.”

- Another described it as “an elevated railroad stairway in ruins after an earthquake.”

The controversy made Duchamp an instant celebrity in America, but the betrayal by the Parisian avant-garde solidified his decision to abandon the traditional canvas forever.

Lesson 3: The Readymade Revolution: The Art of Choice, Not Craft

Duchamp’s most radical gesture was the “Readymade”—a mass-produced object designated as art simply because the artist chose it. He purchased a Bottle Rack (1914) from a Parisian bazaar and a porcelain urinal from J.L. Mott Iron Works in New York, proving that the artist’s hand was secondary to the artist’s mind.

He signed the urinal “R. Mutt,” a complex bit of wordplay referencing the “Mutt and Jeff” comic and the German word Armut (poverty). When the Society of Independent Artists rejected it, Duchamp defended the work anonymously in The Blind Man:

Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it.

This single gesture decoupled art from manual labor. It declared that art is a matter of context and designation, effectively ending the requirement for beauty or craftsmanship.

Lesson 4: The Great Pivot: When Chess Becomes the Purer Art

By the 1920s, Duchamp famously cast aside his brushes, possibly punning on the title of his last canvas Tu m’ (“you annoy/bore me”). He “retired” to focus on chess, which he viewed as a “purer” form of art because it could not be easily commercialized.

Ironically, the man who broke every rule in art was a “conformist” in chess, strictly adhering to classical theories and studying grandmaster games. He wasn’t just a hobbyist; he reached the level of Chess Master in 1925 and represented France in four Olympiads.

- He famously defeated future Grandmaster George Koltanowski in just 15 moves in 1929.

- His obsession was so total that his first wife, Lydie Sarazin-Levassor, reportedly glued his chess pieces to the board during their honeymoon in a desperate act of sabotage.

For Duchamp, chess was the ultimate “gray matter” activity. As he noted:

Chess is much purer than art in its social position… It cannot be commercialised.

Lesson 5: The 20-Year Secret: The Masterpiece Nobody Knew Existed

While the world believed Duchamp had stopped creating, he was secretly spending twenty years (1946–1966) constructing his final statement: Étant donnés. The work remained hidden in his studio until after his death, shocking a public that thought he had retired to play chess.

The piece is a voyeuristic diorama viewed through two peepholes in a weathered wooden door. Inside is a hyper-realistic landscape featuring a nude figure molded from his mistress, Maria Martins.

- The Materials: The figure’s skin is a visceral construction of parchment, leather, and wax.

- The Loop: The work connects back to his earlier masterpiece, The Large Glass, by finally realizing the “Waterfall” and the “Gas Lamp” mentioned in its full title.

- The Experience: The forced perspective and peepholes make the viewer a solitary, uncomfortable voyeur.

This “perpetual surprise” ensured that Duchamp would have the last laugh, completing an intellectual loop that spanned half a century.

Conclusion: There is No Solution Because There is No Problem

Marcel Duchamp’s legacy is the foundation of Pop Art and Minimalism. He taught us that art is not about what we see, but how we think about what we see. Even his female alter-ego, Rrose Sélavy—a pun on Eros, c’est la vie (Eros, that’s life)—served to challenge the identity of the artist.

He died unexpectedly of heart failure in 1968, leaving behind a philosophy of detached observation. His reported last words were: “There is no solution because there is no problem.”

If art is no longer about the physical object but the choice of the observer, what “readymades” are we overlooking in our own lives today?