43-01 Futurism

At the dawn of the 20th century, the traditional art world was a landscape of stagnant values, stubbornly obsessed with the quiet sanctity of museums and the ghost of the Renaissance. To a new generation of Italian radicals, this fixation on the past was more than a bore—it was a terminal illness. The breakneck speed of the machine age had rendered the traditional still life a dusty anachronism, and the stage was set for an iconoclastic assault on the status quo.

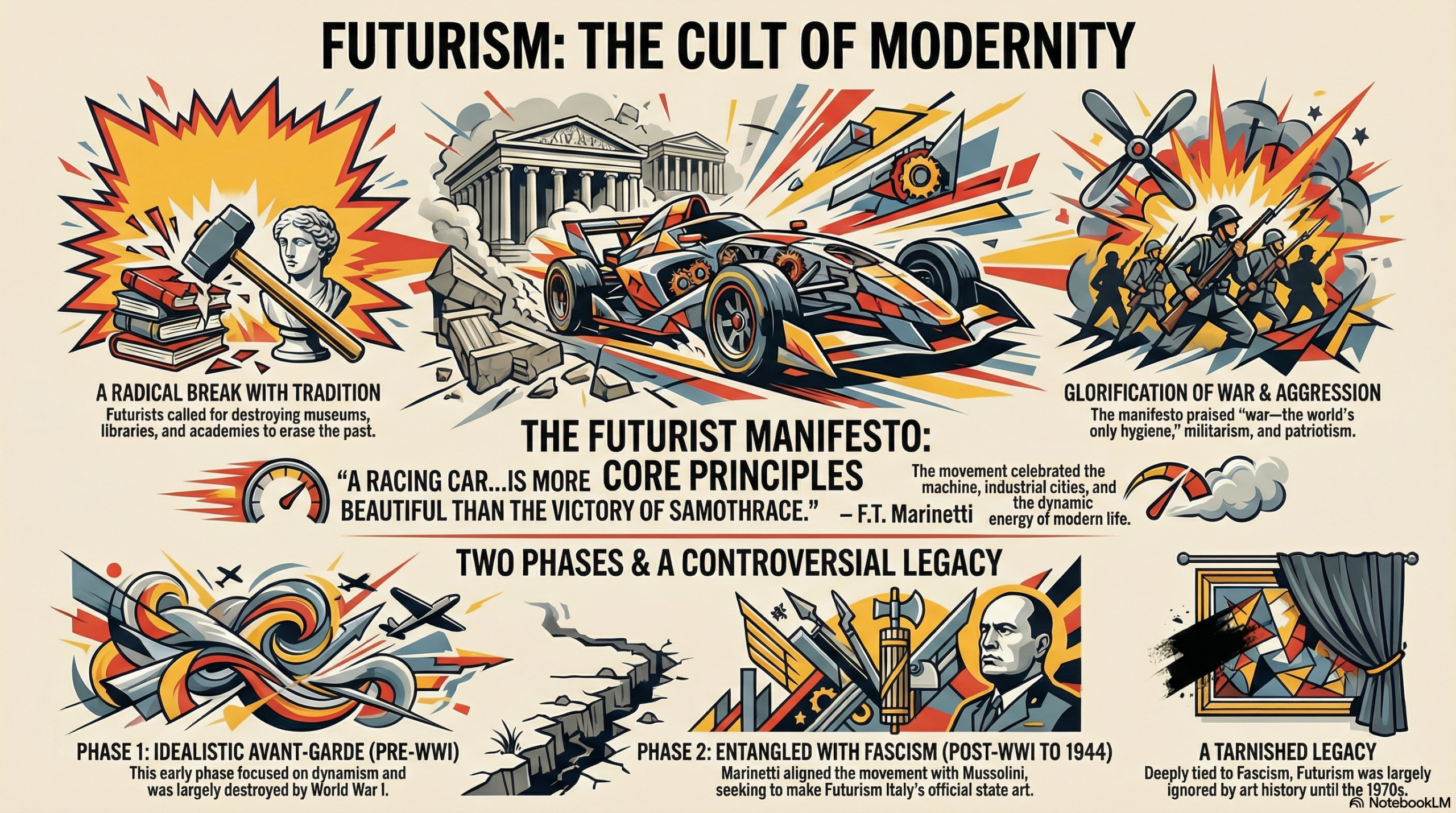

This explosive arrival was Futurism, a movement launched in Italy that glorified modernity, speed, and the relentless hum of industrial progress. It was a totalizing social and artistic project that sought to “reconstruct the universe” through an aesthetic of aggression and kinetic energy. But the movement’s birth was not found in a studio; it was forged in the mud of a suburban ditch.

The High-Speed Revelation: How a Car Wreck Founded an Aesthetic

Futurism’s origin story is perhaps the most violent and counter-intuitive in the history of the avant-garde. In October 1908, the movement’s founder, the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, swerved his car into a ditch to avoid two cyclists. As he climbed from the wreckage, he experienced a profound revelation: the accident was not a disaster, but a baptism into the beauty of technology and the “hygiene” of violence.

He synthesized this polemic into the Futurist Manifesto, published on the front page of Le Figaro on February 20, 1909. Marinetti issued a challenge to the entire history of Western aesthetics with a provocative comparison:

“A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath—a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”

For Marinetti, the adrenaline of a car crash was more vital than any masterpiece in the Louvre. This founding myth established a core Futurist tenet: the aesthetic of the past was dead, and the roaring machine was the only true god of the new century.

Posthumous Contradictions: The Bronze Legacy of a Man Who Hated Bronze

Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) is arguably the movement’s most iconic image—a human figure gliding through space, its body rippling with what Boccioni called “synthetic continuity.” Today, this sculpture is a symbol of national pride, appearing on the Italian 20-cent euro coin. Yet, the bronze versions we see in museums like MoMA are a direct betrayal of the artist’s vision.

Boccioni, who was obsessed with the transient nature of modernity, originally created the work in white plaster. He specifically argued against the use of bronze, associating it with the museum-quality permanence he despised. For a Futurist, art was meant to be ephemeral, destined to be destroyed by more innovative successors. Tragically, Boccioni’s own life was as fleeting as his preferred medium; he died in 1916 at age 34, falling from a horse during military exercises. It was only after his death that Marinetti began producing the robust bronze casts we see today. In a final layer of human irony, it was Boccioni’s widow and heir, Benedetta Cappa Marinetti, who sold the 1931 bronze cast to MoMA in 1948, ensuring the permanence of a legacy that was originally meant to be delicate and temporary.

The Art of Noise: When Painting Wasn’t Loud Enough

For Luigi Russolo, a founding painter, the visual arts eventually proved insufficient to capture the industrial cacophony of the modern city. After painting works like Dynamism of a Car (1913), which used stacked red arrows to illustrate the “Doppler effect” of a passing vehicle, Russolo abandoned his brushes for a more radical pursuit: The Art of Noises.

Collaborating with Ugo Piatti, Russolo built experimental “noise-instruments” designed to bring roars, explosions, and hissing under aesthetic control. His 1913 performance at Rome’s Teatro Costanzi was met with a chaotic reaction; an audience offended by the replacement of melody with industrial noise attacked the performers with “shouts and sticks.” Interestingly, while some critics dismissed Russolo for a “lack of competence” in his painting, this lack of formal subtlety actually enhanced his work. His blunt visual rhetoric and crude brushwork created a deliberate, unapologetic assault on the senses that a more refined painter might have lacked.

The Paradox of Progress: Scorn for Women vs. the Warrior Female

The 1909 Manifesto is notorious for its “scorn for woman” and its rejection of feminism. However, for a historian, the reality is far more nuanced. Marinetti’s “scorn” was aimed at the Romantic ideal of the “fainting weakling.” Paradoxically, he advocated for radical social reforms that were decades ahead of their time, including:

• The abolition of traditional marriage and the legalization of easy divorce.

• The right for women to vote and receive equal pay.

The movement sought to transform women into “warriors.” While the Italian movement struggled with these internal contradictions, its Russian counterpart—including figures like Natalia Goncharova, Aleksandra Ekster, and Lyubov Popova—boasted a much higher percentage of influential women from the start.

The ultimate Italian “warrior” was Benedetta Cappa Marinetti. A key figure of Aeropittura (aeropainting), she was the first woman to exhibit at the Venice Biennale (appearing from 1930-1936). Her masterpiece, the massive frescoes titled Synthesis of Aerial Communications (1933-34) for the Post Office Building in Palermo, remains the final link to the movement’s founding generation. She helped “reconstruct the universe” through everything from Futurist toys to clothing, proving women were central to the movement’s late survival.

The Double-Edged Sword: Innovation vs. Fascist Alignment

The most contentious aspect of Futurism is its deep-seated relationship with Benito Mussolini. The movement’s history is best viewed as a drama in two waves:

1. The First Wave (Pre-WWI): An idealistic, radical period of abstract modernity that was largely destroyed by the very war it glorified.

2. The Second Wave (Post-WWI): A longer phase where Marinetti—who co-authored the 1919 Fascist Manifesto—formed a pragmatic relationship with the state.

While Futurism provided the cultural “blueprint” for Fascism through its glorification of war as “the world’s only hygiene,” a tension always existed. The Futurists demanded radical modernity, while Mussolini increasingly preferred romanità—a neoclassical appeal to Roman imperial glory. Second-wave Futurism became a survival strategy, seeking state patronage while maintaining an experimental edge that the regime often found “degenerate.” This association served as the movement’s death knell after 1945, when it was largely scrubbed from art history for decades as “the art of the enemy.”

Conclusion: A Universe Reconstructed

Futurism successfully expanded the boundaries of art into “plastic complexes”—a total environment of furniture, toys, and clothing designed to reflect a mechanised harmony. It was a movement that refused to be contained by a frame, seeking instead a total “reconstruction of the universe.”

The movement reached its final curtain on December 2, 1944, with Marinetti’s death, but its influence lingers as a haunting question for the modern era: Can an artist’s revolutionary innovations ever be truly separated from their political consequences? Regardless of the answer, Futurism remains a deliberate, unapologetic assault on the senses that fundamentally shifted the trajectory of the 20th century.