42-01 Expressionism

The Inner Earthquake: A Turn Inward

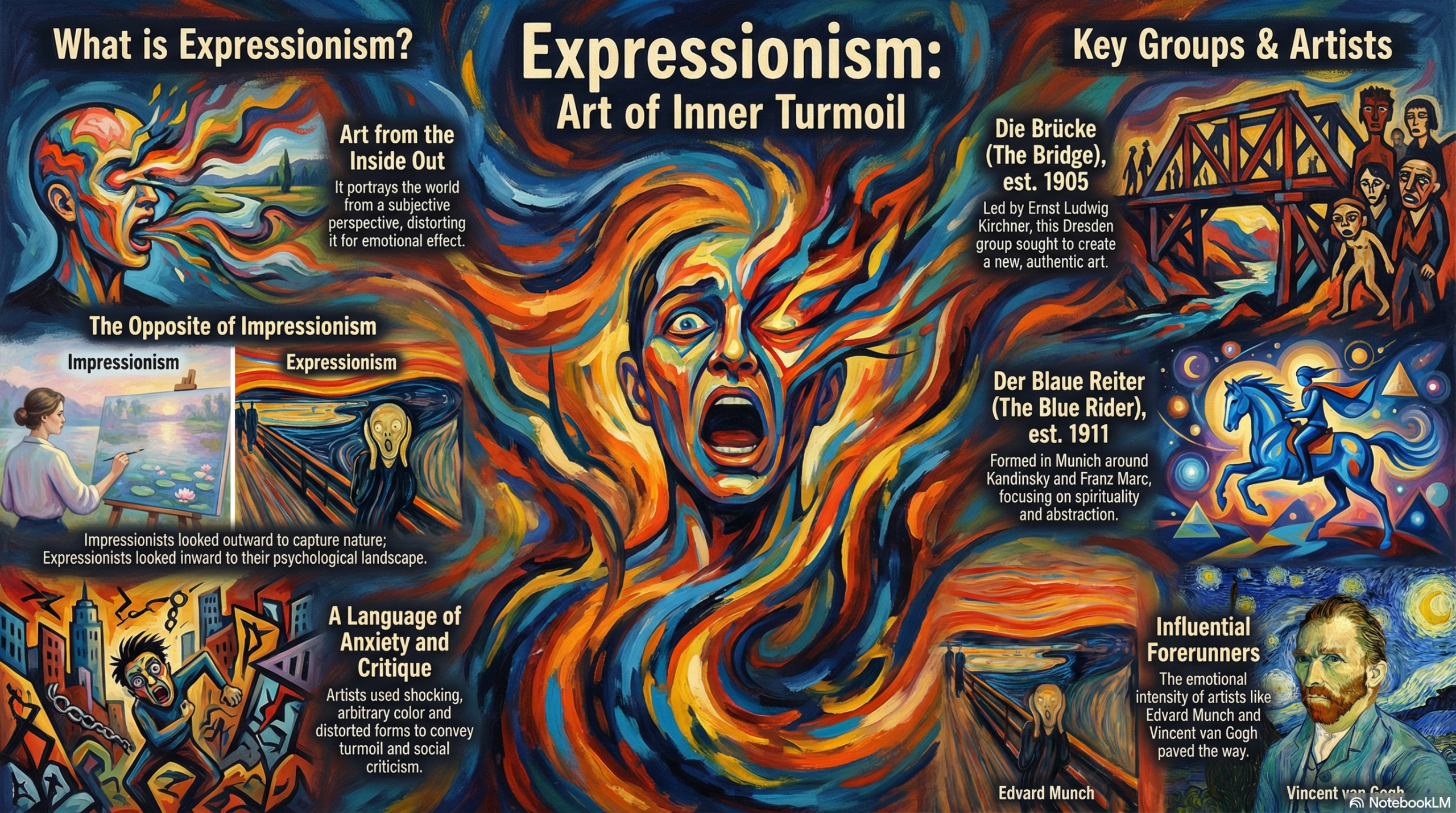

Art history is a pendulum swinging between the world we see and the world we feel. At the turn of the 20th century, Expressionism erupted in Northern Europe as a violent rejection of Impressionism’s “superficial naturalism.” While the Impressionists looked outward to capture the fleeting dance of light, the Expressionists looked inward, distorting reality to achieve a raw emotional impact.

In 1910, Czech art historian Antonin Matějček defined the movement as the literal inverse of Impressionism. It was no longer about a faithful rendering of nature; it was about the “inner earthquake.” This shift prompts a hauntingly modern question: In an era where the external world feels like it is dissolving, how do we use art to map the tremors of our own internal anxiety?

- A Note from a “Madman”: The Panic Behind the Icon

Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) is the definitive logo for modern dread, but it was not merely an exercise in style—it was a documented psychological collapse. While walking near a fjord at sunset, Munch was overtaken by a panic attack so visceral that the boundary between his mind and the landscape dissolved.

“I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature,” Munch wrote, describing how the sun set and the clouds turned “blood red.”

This was a period of profound personal trauma. Munch’s mother and sister Sophie had already been taken by tuberculosis; his father died when he was twenty-five. Most chillingly, at the exact time Munch was painting The Scream, his sister Laura had been interned in an asylum. On one version of the painting, a tiny, scrawled note in Norwegian script serves as a final, desperate testament: “Could only have been painted by a madman.” - The Spiritual Blue: Why Franz Marc’s Horses Weren’t “Natural”

For the group Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), color was a vessel for spiritual truth rather than zoological accuracy. The group’s origin was born of friction; it formed in 1911 after Wassily Kandinsky’s painting The Last Judgment was rejected from a local exhibition. They took their name from a 1903 Kandinsky piece, signaling a focus on metaphysical symbolism.

Franz Marc developed a rigid color theory to navigate this spiritual landscape:

- Blue: Masculine, intellectual, and spiritual. The darker the shade, the more it called to the eternal.

- Yellow: Feminine, gentle, and joyful.

- Red: Violent and heavy, representing base matter.

Marc viewed animals as “virginal” beings, closer to God and more spiritually pure than corrupted humanity. His career reached its zenith with Fighting Forms (1914), where he pushed past representation into pure abstraction, depicting red and blue forms locked in a cosmic struggle. Tragically, this journey into the infinite was cut short when Marc was killed by a shell splinter at the Battle of Verdun in 1916.

- The Symbolic Amputation: Kirchner’s Fear of Artistic Death

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, a founder of the Die Brücke (The Bridge) group, was the poet laureate of Berlin’s frantic, urban energy. He captured a city defined by a sharp paradox: glamour offset by alienation.

Modernity as Commodity In his street scenes, Kirchner used the prostitute as the ultimate symbol of the metropolis. She represented intimacy offset by isolation—a world where everything, including the human soul, was a commodity.

The Fear of Artistic Silence When Kirchner volunteered for military service in 1915, the experience shattered him. His Self-Portrait as a Soldier depicts him in uniform with a bloody, severed stump for a right hand. The injury was not literal; it was a symbolic amputation.

For Kirchner, the hand was the instrument of creation. Its loss represented “artistic death” and his terror that the war had permanently silenced his ability to create. Haunted and broken, Kirchner never fully recovered, eventually taking his own life in 1938. - The Artist Who Saw the Future: Meidner’s Apocalyptic Premonitions

Between 1912 and 1914, Ludwig Meidner produced a series of Apocalyptic Landscapes that were terrifyingly prescient. Years before the first shells fell on European soil, Meidner was painting cities in the throes of total destruction—buildings exploding and collapsing at impossible angles under skies filled with comets and cosmic disturbances.

Meidner claimed these works were born of a “premonition” of coming disaster. His fractured perspectives and chaotic compositions provided the perfect visual vocabulary for the underlying European anxiety of the era. Whether his visions were truly prophetic or a reaction to the mounting political tension, they remain the most powerful images of impending catastrophe in the history of German Expressionism. - Breaking the Bourgeois: Nudity and Masks as Social Rebellion

Expressionists wielded “grotesque” and “primitive” elements like weapons against the stiff social mores of the bourgeois class. They sought an “elemental force” that could bypass the artificiality of Western academic traditions.

“For the Expressionists, the naked body was a potent site for challenging traditions of beauty and propriety.” — Museum of Modern Art

In Paul Klee’s Virgin in the Tree (1903), the artist mocks erotic expectations by depicting a “desiccated” female body with withered breasts and jagged hips, mirroring the gnarly bark of a barren tree. Similarly, Emil Nolde sought “elemental force” through the study of non-European artifacts. His work Masks (1911) was directly inspired by items he sketched in Berlin’s Museum of Ethnology, including a Solomon Islands canoe prow and the shrunken head of a Yoruna Indian. - The Ultimate Obsession: Kokoschka and the Life-Sized Doll

The Austrian “enfant terrible” Oskar Kokoschka channeled his personal trauma with a literalism that bordered on the macabre. His romance with Alma Mahler was a psychological storm of “insane” obsession. While painting The Bride of the Wind (1914), the poet George Trakl would sit in the studio in an alcoholic haze, whispering poems that fueled the work’s frantic, swirling energy.

The relationship’s end was horrific. Kokoschka reportedly tortured Alma by showing her the bloody cotton wool from her abortion, claiming it was his “only child.” When she eventually married another man, Kokoschka commissioned a life-sized doll made to her exact specifications. This obsession reached an orgiastic climax at a party in 1919, where Kokoschka famously beheaded the doll in his atelier to symbolically sever himself from the “curse” of the relationship. - The Aftermath: From Cleansing Fire to Moral Chaos

Early Expressionists often welcomed the First World War as a “cleansing fire” that would purify a decaying society. This optimism died in the trenches. The movement shifted into Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), where the “regenerative impulse” was replaced by scathing social satire.

In Max Beckmann’s The Night, the artist uses his own family as models to depict a horrific home invasion, representing a society descending into bestial madness. George Grosz took this cynicism further in his 1920 work, Daum marries her pedantic automaton George in May 1920, John Heartfield is very glad of it.

Grosz depicted himself as a pedantic automaton—a de-sensitized, mechanical man obsessed with arithmetical problems. The name “Daum” was a coded anagram for his wife’s nickname, “Maud,” and the inclusion of fellow Dadaist John Heartfield in the title anchored the work in an anti-art movement that viewed the post-war world as a moral void. - A Legacy of Unfiltered Emotion

The Expressionist journey was eventually met with state-sponsored suppression. Under the Nazi regime, these works were branded as “Degenerate Art” (Entartete Kunst), leading to the destruction of masterpieces and the exile or suicide of the artists who created them.

Yet, their legacy of “unfiltered” emotion remains essential. In our current era of algorithmic curated identities and digital filters, is there still a place for the raw, distorted, and uncomfortably honest “inner landscape” of the Expressionists? Perhaps, like Grosz’s pedantic automaton, we are in danger of losing our humanity to the “arithmetical problems” of our own age, making the Expressionists’ scream more relevant than ever.